Anxieties of Influence

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

29/11/2019

Leonardo DiCaprio as Dom Cobb in Inception

“What is the most resilient parasite?” asks Leonardo DiCaprio’s character, Dom Cobb, in the movie Inception.

“An idea,” he answers. “Resilient, highly contagious. Once an idea has taken hold in the brain, it’s almost impossible to eradicate.”

Such is the attitude many liberals seem to have nowadays. On university campuses in the UK and the US, they cancel or shut down talks by speakers they disagree with, often claiming their ideas are not worth listening to. The twin shocks of the Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump have exacerbated this, with many now calling for more constraints on free expression, at events, on television, on social media, because some opinions are so wrong or sexist or racist or hateful or inflammatory that they pose a threat to liberal democracy.

Perhaps no one has taken this call to heart more than Twitter Founder and CEO Jack Dorsey, who recently banned all political ads on the platform citing the risks “misleading” political ads pose to politics. (This ban will likely restrict not just ads by politicians and their supporters, but news articles, documentaries, and campaigns produced by independent entities that touch on political or social issues, too.) Last week, actor and comedian Sacha Baron Cohen excoriated social media companies for being insufficiently tough on misinformation and hate speech. There is a new censoriousness in the air. Some ideas, it seems, are too hazardous to be given a chance to spread. Many liberals have come to view unfamiliar or opposing ideas not as potential stimulants to thought or opportunities to learn, but as parasitic, contagious, dangerous.

Dictators everywhere are happy to hear this; it gives them license to crack down on ideas they deem dangerous. The Singaporean government has capitalized on US paranoia about Russian influence to persecute alternative news sites like The Online Citizen for “foreign influence,” because some of its op-ed writers are foreigners. In an article in Foreign Policy, “Germany’s Online Crackdowns Inspire the World’s Dictators,” Jacob Mchangama, executive director of Justitia, a Copenhagen-based think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law, and Joelle Fiss, a human rights expert, wrote that a German anti-hate speech law has been copied by authoritarian states like Russia, Singapore, Venezuela, and Vietnam. Donald Trump popularized the term “fake news” on the campaign trail, but, like a bad habit, it’s caught on with liberals too, some of whom use it to discredit and call for the removal of material they vehemently disagree with. Predictably, dictators have used this to their advantage. “Fake news!” is what Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro calls stories on his repression. “Fake news!” is what former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak called exposes on the 1MDB corruption scandal enveloping him. “Fake news!” is what Syrian President Bashar al-Assad calls Amnesty International reports on his regime’s butchery. After all, if the president of the United States and liberals in the freest countries in the world do it, why shouldn’t they?

Donald Trump popularized the term “fake news” on the campaign trail, but it’s caught on with liberals too.

One of the few public figures to take a stand against the calls for censoring or restricting the reach of certain social and political ideas is Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook (though Facebook’s requirement of a local mailing address to run “political ads” in each country is still unnecessarily onerous). In a speech at Georgetown University in October, he outlined how his company has rightly cracked down on fake accounts (accounts that pretend to be people they’re not). He expressed alarm, however, at the rising calls for censorship in the name of protecting democracy. “Increasingly, we’re seeing people try to define more speech as dangerous because it may lead to political outcomes they see as unacceptable,” he said. “Some hold the view that since the stakes are so high, they can no longer trust their fellow citizens with the power to communicate and decide what to believe for themselves. I personally believe this is more dangerous for democracy over the long term than almost any speech. Democracy depends on the idea that we hold each others’ right to express ourselves and be heard above our own desire to always get the outcomes we want.”

He’s right. Democracy is premised on the idea that people have the freedom to choose for themselves what to believe, what to share, and what to vote for – and freedom of choice must include the freedom to choose wrongly. They might not get it right all the time, but confidence in the system requires only that, as E. B. White wrote, “more than half of the people are right more than half of the time.” Calls to restrict the spread of certain ideas because they’re supposedly dangerous reflect a lack of confidence in democracy and in the people. Contrast Zuckerberg’s speech with Dorsey’s tweets explaining why Twitter is banning political ads:

A political message earns reach when people decide to follow an account or retweet. Paying for reach removes that decision, forcing highly optimized and targeted political messages on people.

In Dorsey’s estimation, people are like mindless automatons, who have no choice but to follow an account or retweet a post if it’s put in front of them.

Of course, there are good reasons for this anxiety of influence, this shaken confidence in the mental and moral capabilities of fellow citizens to make important decisions, to distinguish right from wrong, truth from falsehood – chief among them being Donald Trump’s presidency. How could such a large part of the country not only choose someone so obviously unfit for the office, but go on to defend his administration even though he proves himself more and more unfit with each passing day? Because they were brainwashed by misinformation, hate speech, and fascist ideology fed to them through micro-targeting systems on social media, goes a certain liberal argument. (Funnily enough, as Steven Law, president of the Senate Leadership Fund, a Republican super PAC, pointed out in his Wall Street Journal article “Don’t Buy the Outrage Over Digital Ads,” liberals praised the same social media micro-targeting tactics when they were used to help Barack Obama’s reelection in 2012.)

Picture Credit: Gage Skidmore

But it’s unfair to shift the responsibility for things like Trump’s presidency to social media, which are just neutral platforms, when the bulk of the blame ultimately rests with the people themselves. It was Republican voters who, when given the choice of 16 other major candidates, chose Trump as their nominee. It was the American people who chose Trump over Hillary Clinton. It was many of these people who, when given the choice of The Atlantic, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal, chose to read, believe, and share Breitbart and Infowars instead. “[F]iguring out when politicians are full of shit is the responsibility of the voters and no one else,” said the comedian Bill Maher. “People have to build up an immunity to falsehoods. We can’t pass the buck to a referee.” In a democracy, there is no substitute for an intelligent and critical populace (at least to a minimum level). And if such standards are beyond it, if the majority of the people (or near enough as to make no difference) are too stupid to weigh ideas critically and to be allowed to choose for themselves, then the logical conclusion is not that dangerous ideas should be kept from them, but that they shouldn’t be allowed to choose in the first place – that democracy is not appropriate for that country, and that it would be better off under an enlightened dictatorship.

In a democracy, there is no substitute for an intelligent and critical populace (at least to a minimum level).

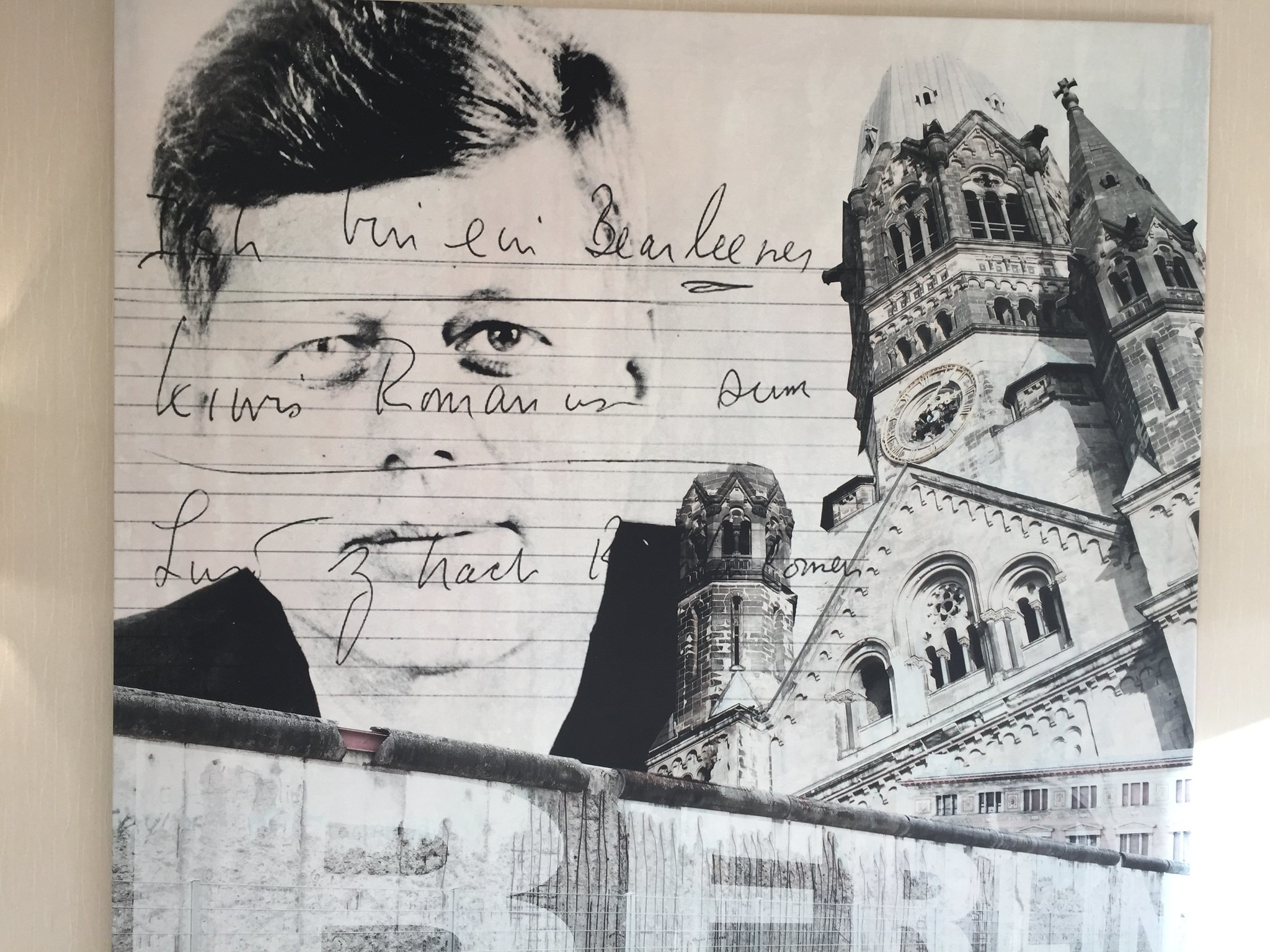

Maybe liberals would have more confidence in the power of their own ideas, however, if they took a wider perspective. Around the globe, liberal democratic ideas are rightly feared by those in power far more than fascist ones. There’s a reason why North Korea fears the inflow of ideas from South Korea – through illicit broadcasts and smuggled flash drives – and not the other way round. There’s a reason why the US is an open society and China erects a Great Firewall around itself. There’s a reason why democratic ideals resonate with people the world over, whilst authoritarian regime propaganda often can’t even convince their captive audiences. It’s because liberal democratic ideas are much stronger and more attractive than fascist ones, because when they clash on a level playing field they tend to win. “Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in,” said John F. Kennedy in West Berlin during the Cold War. By this, he also meant mental walls. “We welcome the view of others,” he said at the 20th anniversary of the Voice of America. “We seek a free flow of information across national boundaries and oceans, across iron curtains and stone walls. We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.”

Picture Credit: Andy Blackledge

“Let a hundred flowers bloom,” declared Chairman Mao Zedong in February 1957, in support of a new campaign to encourage more open discourse in China, “let a hundred schools of thought contend.”

By July 1957, Mao, shocked by the outpouring of criticism against the Chinese Communist Party at rallies, in magazines, on posters stuck to the “Democratic Wall” at Peking University, had to discontinue the campaign (and imprisoned many people who had taken him at his word and spoken too candidly). He couldn’t live up to that ideal. Dictatorships never can. That only liberal democracies are capable of doing so is part of their enduring appeal. Perhaps if some liberals believed in the power of liberal democratic ideas half as much as fascists do, they wouldn’t be so anxious.