Big Boss Is Watching You

By Gurwinder Bhogal

Staff Writer

26/6/2020

Imagine a world where you are constantly being tracked and monitored in your own home by your boss, a world where every email you send, every keystroke you type on your computer, even the movement of your eyes, is recorded to decipher not just how you are working but how you are feeling.

Such a world may be approaching.

The coronavirus pandemic has forced many businesses to shift to a telecommuting model in which employees work remotely from home. According to an MIT study, a third of the entire US workforce had switched to telecommuting by April due to the virus, the same proportion as those who can telecommute. The measures were intended only to be temporary, but they have proven so successful that many employers are now tempted to make them permanent. In a Gartner survey of 341 CFOs, 74% said they expect to make temporary teleworkers permanent post-COVID. TCS, India’s largest IT multinational, has announced that 75% of its 450,000 employees will permanently work from home by 2025. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg expects half of his entire workforce to telecommute over the next few years, while Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey told many of his employees that they’re free to work from home forever.

For many, this is good news, because the prospect of telecommuting is much desired by employees. In a 2017 Gallup poll of nearly 200,000 workers, 54% said they’d leave their job for one that offers more flexible working arrangements. It’s easy to see why remote work is so attractive: it allows you to set your own schedule, work in an environment that suits you, and free up time and money that would be spent on a daily commute.

It’s tempting to view these freedoms as indications that the telecommuting revolution will liberate workers from the constraints of the office, but this might not be true. Far from offering workers more autonomy from their bosses, the telecommuting revolution may in fact force them to relinquish what autonomy they still had.

Far from offering workers more autonomy from their bosses, the telecommuting revolution may in fact force them to relinquish what autonomy they still had.

One of the problems with teleworking is that it makes it hard for employers to get to know their employees. Without being able to see what their workers are doing, employers have trouble discerning how hard they are working or even who they actually are, which can stifle empathy and trust. This may help explain why teleworkers are less likely to be considered for promotion than their office-based colleagues, despite generally being more productive.

Clearly, this is a problem. But the solution is potentially much worse.

As telecommuting has become widespread and the availability of face-to-face scrutiny has dwindled, employers have increasingly sought new ways of getting to know their employees, no matter how intrusive. Amazon has developed a wristband that tracks the movements of its workers across its vast warehouses. In China, employees at firms like State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power wear hats fitted with sensors that relay their brainwaves to computers that detect irregularities in employees’ emotional states like anxiety, depression, or rage. Cheng Jingzhou, an official overseeing the company’s emotional surveillance program, claims it has increased the company’s profits by $315 million since it was rolled out in 2014.

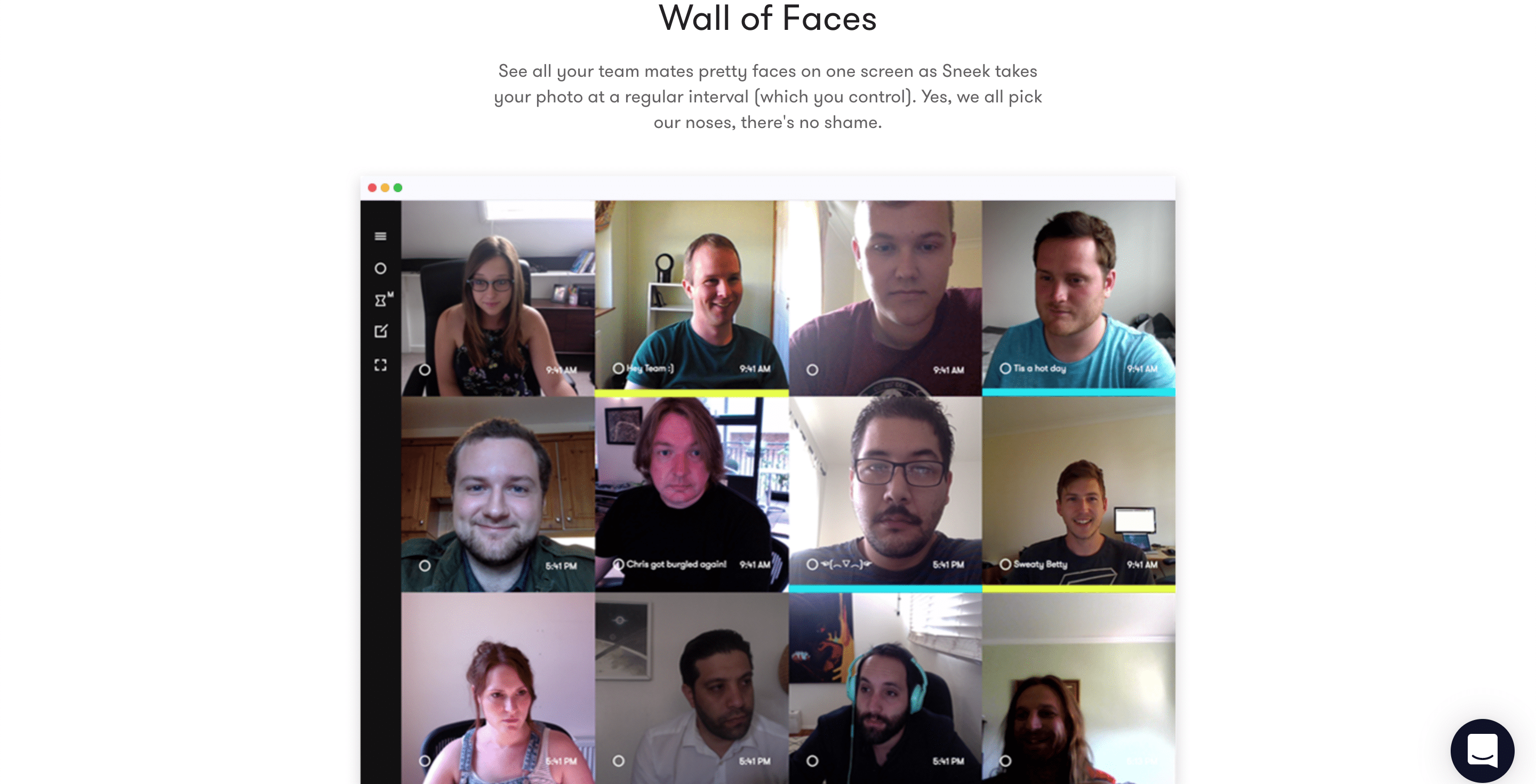

One might think telecommuters working on the other side of the world from their employer would be spared this kind of surveillance. But it’s even easier for an employer to monitor a telecommuter than a regular employee, due to the wealth of surveillance software that can now be installed on computers. Programs like Veriato Cerebral can be used for “sentiment analysis”: digitally scanning workers’ private messages in order to build a picture of their state of mind. Certain words can be flagged so that if they appear in a message sent by an employee, the employer will be notified. Such software can also track your keystrokes, record your Google searches, and screenshot your computer. Other programs, like the always-on videoconferencing app Sneek, constantly take (and publicly display) a webcam photo of each worker’s face every few minutes, which can be used like a kind of digital panopticon, ensuring everyone is (or at least looks) focused.

Screenshot from Sneek’s website

Employee-monitoring technologies are used for a variety of reasons; they may help guard against corporate espionage, ensuring employees aren’t giving away trade secrets, or they may provide legal protections like video evidence in the case of lawsuits. But the most common use of these technologies is to monitor productivity, which can comprise anything from measuring the speed at which figures are entered into a spreadsheet to tracking eye movements to determine where employees are directing their attention.

The research firm Gartner surveyed 239 large corporations and found that over half of them were using “non-traditional” employee-monitoring techniques like those mentioned above, an increase of one third from 2015. This trend appears to have accelerated with the pandemic-driven surge in remote work. Hubstaff, which provides tools to track remote workers, reported the number of companies trialing its technology had grown by two to three times in the last few months, while another employee-monitoring company, Prodoscore, saw interest from prospective customers rise 600%.

The responses of employees to their employers’ increased efforts to track them have been mixed. Earlier this year the videoconferencing app Zoom had a feature called “attention tracking” that allowed hosts of online meetings to secretly track the eye-movements of participants in order to determine whether they were paying attention, but this feature was promptly removed after word of it went viral, causing an outcry. A backlash also forced Barclays to scrap its plans to use sensors to track the time workers spent at their desks (and issue warnings to slackers). However, such rebellions are the exception; non-traditional supervision is, according to Gartner’s research, something employees are gradually becoming more accepting of, provided they’re informed of it in advance. In 2015, 10%, of surveyed employees were comfortable with their employer monitoring their email. In 2018, this had risen to 30%.

Zoom’s “attention tracking” feature allowed hosts of online meetings to secretly track the eye-movements of participants in order to determine whether they were paying attention.

When it comes to monitoring what workers do outside the office, the public is understandably a lot less accommodating. In a survey conducted by the British trade union body TUC, nearly 70% of respondents claimed they would consent to the monitoring of work emails, files, and browser history, but only 30% claimed they would consent to the monitoring of social media use outside office hours.

But what are office hours if one has no office? Herein lies a key problem with monitoring telecommuters. Unlike Amazon’s wristbands or China’s brain-reading hats, the software used to spy on remote workers isn’t taken off at the end of the workday. It lingers on in the system perpetually, often indiscriminate in the activity it records, potentially blurring the line between monitoring employees’ work and monitoring their lives. If, while working in an office, you write an email to a friend explaining why you’ll support a certain candidate in the next election, and this is flagged and reported by the software, it’s a matter of concern for employers because you’re using time they’re paying you for to do something that isn’t what they’re paying you for. But if you send such a message as a telecommuter, then, even if it occurred during your own “out of office” hours, it may still be flagged, and now your employer will know your political views and other potentially incriminating details without you giving it to them.

Personal data that’s recorded in this way can be misused in several ways; a partisan employer might become prejudiced toward you based on your personal views, an unscrupulous employer might sell your browsing habits to other businesses, a voyeuristic employer could even collect compromising webcam snapshots of you in your home.

It is of course true that if you catch your boss covertly spying on you in a particularly egregious way, you can take them to court; when it transpired that teachers at Lower Merion School District in Philadelphia had been secretly taking snapshots of students in their homes through their webcams, and punishing them for what they did in their own bedrooms, they were hit with a class action lawsuit and forced to settle for $610,000. However, given the nebulous nature of the web, most data laws and online privacy rights are in practice difficult to enforce, and in any case most offer only partial and conditional protection. In the US the main federal law that protects workers from the excesses of employer surveillance is the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), but this has three problems. Firstly, it does not protect the digital privacy of employees who use company-owned hardware like laptops. Secondly, it has several loopholes like the business use exception, which allows the use of employee monitoring if it’s deemed to be in legitimate business interests. Thirdly, data laws like the ECPA can be circumvented with simple consent; if a teleworker agrees to be monitored, wittingly or as a result of not reading the small print, then they usually waive any legal protections covering the information that is discovered as a result of being monitored.

Curiously, consent to be tracked and monitored outside the office does not appear to be hard to obtain. Despite what people say they would accept in surveys, they are not above accommodating significant invasions of privacy for the sake of mere convenience. At Three Market Square, a Wisconsin vending machine company, many employees have opted to have a chip implanted under their skin to make it easier to swipe into buildings and pay for cafeteria food. Meanwhile, millions continue to flock to Facebook despite all the controversy about it stealing and illicitly sharing private information. The conveniences it offers are more visible than the rights it takes away.

Despite the 2018 scandal in which Cambridge Analytica harvested millions of Facebook users’ personal data for political advertising, many people continue to use Facebook (Picture Credit: Book Catalog)

Having one’s data harvested by Facebook is now considered an acceptable cost of using its services. Equally, being monitored by an employer may one day be considered an acceptable cost of teleworking for them. This will certainly become true if employers make consenting to surveillance a condition of employment, which, given the obvious advantages of knowing what one’s employees are doing, may well be the case.

Being monitored by an employer may one day be considered an acceptable cost of teleworking for them.

One might argue that not every employer would demand this, and in a telecommuting world, where employees are no longer limited to employers in close proximity to them, they would easily be able to find a boss who doesn’t spy on his workers. But if telecommuting widens the range of potential employers for employees, then it also widens the range of potential employees for employers. Those who hire tend to be in greater demand than those who want to be hired – which will become even truer if we enter an economic depression – so the likely overall result is that employers will become more selective; anything that can be done cheaply would be outsourced, but high tier jobs, being comparatively few, could become far more competitive, with higher barriers to entry and more bargaining power for employers.

In the end, the degree to which workers are scrutinized by their bosses will not be dictated by laws, but by the market. Ultimately, businesses will have to decide whether their increasingly intrusive methods of surveillance will boost productivity more than loss of employees’ goodwill will hurt it.

A telecommuting revolution offers many freedoms, but autonomy may not be one of them. It may, as many hope, free us from the office; but we should take care it doesn’t also free the office from the office, so it seeps into our homes and becomes something we can never truly escape.