Catullus: The Original Emo Rhapsodist

By Felix Behr

Staff Writer

12/7/2019

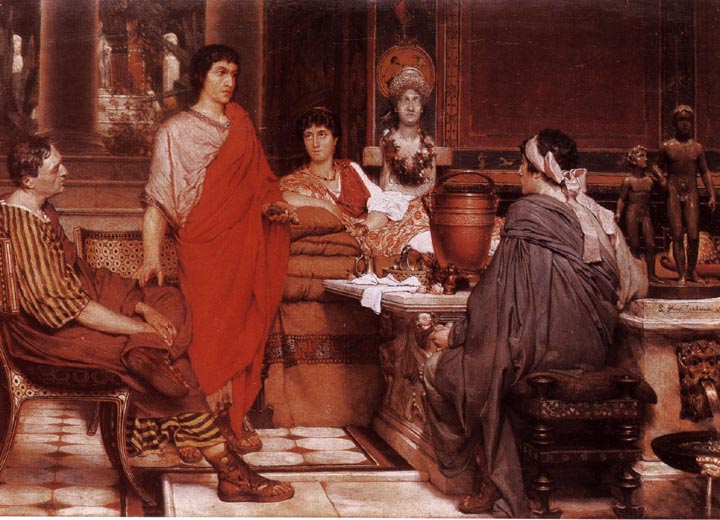

Catullus (second from left), in Catullus at Lesbia’s by Sir Laurence Alma Tadema

The most hard-edged and intense of the Latin poets.

– Ezra Pound

Before boybands were branded across the world, before Rimbaud ran off to Africa, before Byron was mad, bad, and dangerous to know, the verses of Gaius Valerius Catullus blazed through ancient Rome. He never became one of the classical poets. In fact, he barely made it out of antiquity. A single manuscript discovered in 14th century Verona, his hometown, served as the ark for his work until it was copied (badly) and disappeared. A few centuries later, he became my favorite Roman poet.

Like many others, I was introduced to Catullus as a reprieve from all the lines of amos, amases, and amats of Latin 101 (for those to whom this means nothing, the centurion’s correction of Brian’s graffitied “Romanes eunt domus” in Monty Python’s The Life of Brian captures the drudgery of learning Latin). Catullus is a treat for these suffering students because he is the first poetic emo in the West. That and the fact that he was really vulgar.

Catullus invented the angry young poet. And, since Greco-Roman poetry focused on forming a separate persona for the poem’s performance, Catullus invented Catullus, a persona that was volcanic in his passions and shocking in his obscenity.

Catullus invented the angry young poet.

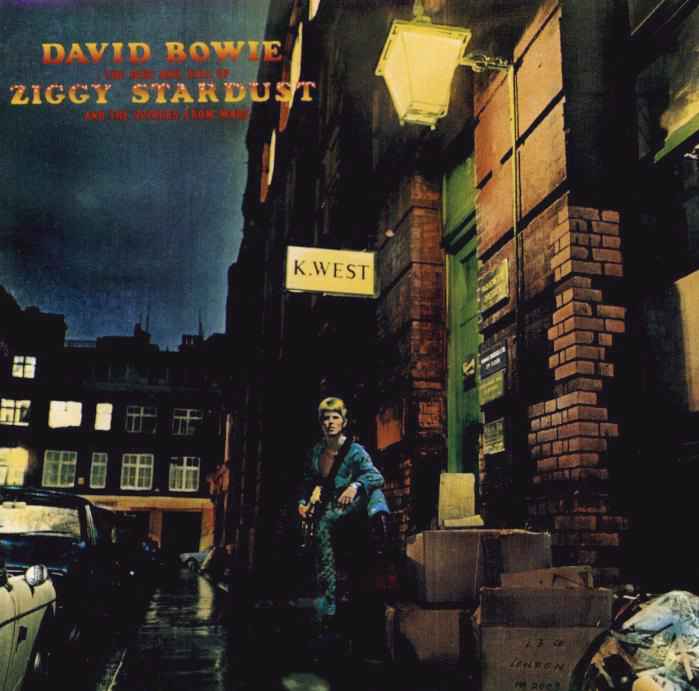

The removed rhetorical poet stands in sharp contrast to the poet of popular imagination who wears black and repurposes their tears as ink. It’s really more similar to pop stars, the best example being another favorite of mine, David Bowie, best remembered as Ziggy Stardust, an androgynous bisexual rock ’n roll messiah from outer space with a flaming red mullet and outrageous outfits. He was a character Bowie created and embodied fully for the 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. Later he reflected on the nature of such personas in an interview, explaining that, “Most rock characters one can create only have a short lifespan. They are one-shots. They are cartoons. The Ziggy thing was worth about one or two albums before I couldn’t really write anything else around him or the world I put together for him.” Other personas, like Beyonce’s Sasha Fierce, aren’t so “out there,” operating more as a personality for a performance than a character.

While his personality may better resemble Sasha Fierce, Catullus’ character serves a role more similar to Ziggy Stardust. Like David Bowie and Ziggy, Catullus infuses a personality into his work to such a degree that separating the personal from the persona is impossible. A creation emerges whose individual personality is more complex and believable than most modern writers who are expected to crucify their souls upon the page.

Catullus infuses a personality into his work to such a degree that separating the personal from the persona is impossible.

This is just as well, for almost all we know of Catullus comes from the poems that survived in that single Veronese manuscript. We believe he compiled his poems into a book because Catullus 1 is about him donating his new book to an early supporter. No one knows how this book would have been organized, however. The numbers most use as titles for Catullus’ poems merely refer to the order people found in the manuscript.

That said, from the details his poems drop as well as a smattering of references to him in the work of other writers, like Ovid, we’ve managed to get an impression of Catullus’ life.

Catullus was a young man whose life approximately spanned 84 BC to 54 BC, pretty much covering the time leading up to the Roman Republic’s demise. He was aristocratic enough that he could write rudely about his contemporaries, including Julius Caesar and Cicero, with relative impunity. He worked a minor staff role for the governor of Bythinia (now Asia Minor) from 57-56 BC.

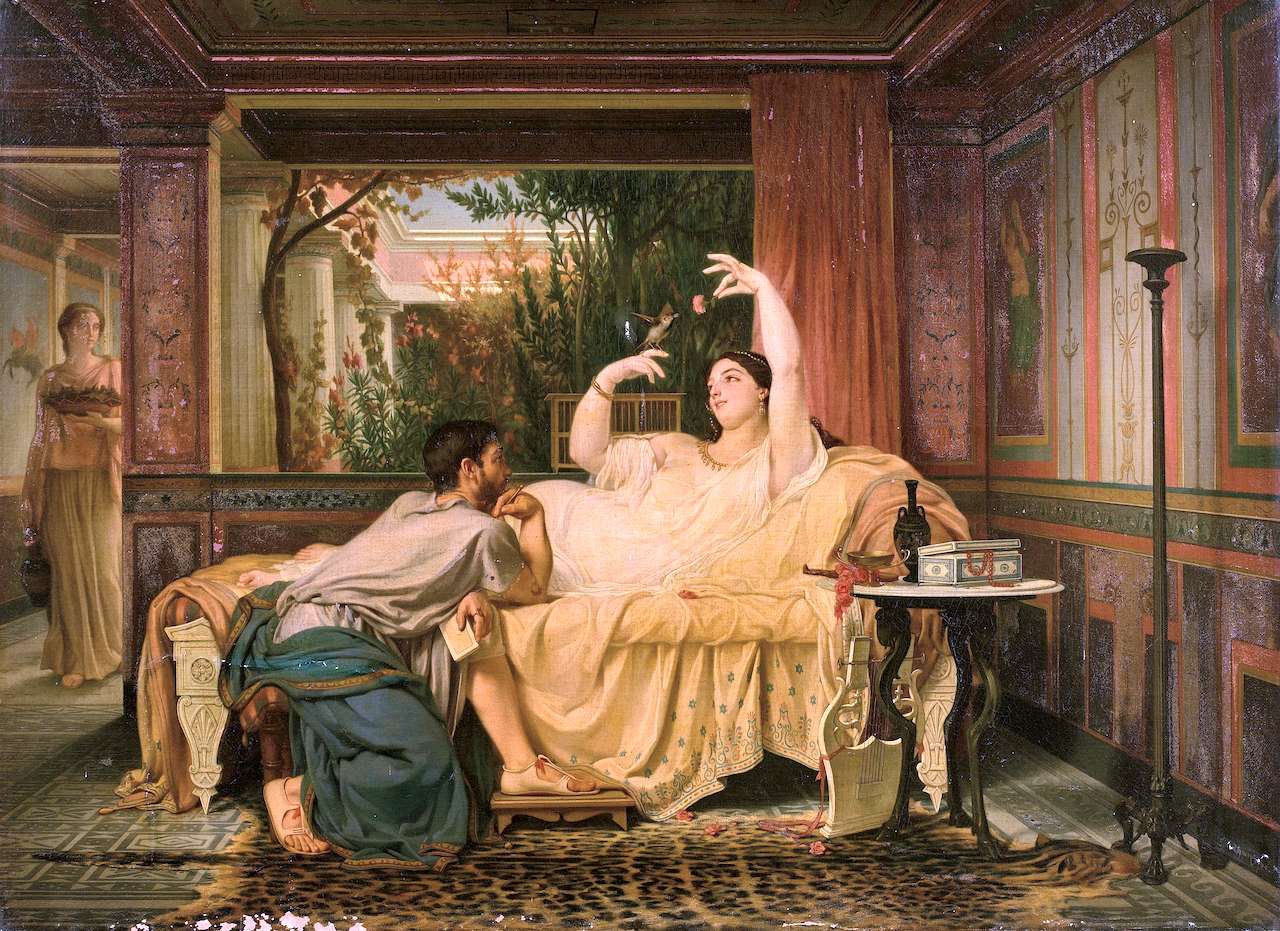

Depiction of Catullus

However, unlike many men of his class, he was uninvolved in politics, preferring to read and write funny, emotional, and erudite poems about his immediate life to stirring the Senate with oratory. He was the leading voice of the avant-garde neoterics (new poets) who largely eschewed epics and other weighty subjects in favor of short, immediate, and fresh poems that dealt with daily life, such as calling out a bore who stole a napkin.

Besides the death of his brother, the biggest drama of Catullus’ life is Lesbia. 25 of Catullus’ poems, including Poem 85, deal with his feelings for a woman he called Lesbia. Many suspect an older patrician woman named Clodia Pulchra as Catullus’ real Lesbia. But as with Catullus, she primarily serves as a vehicle for the poetry’s narrative.

Lesbia and her Sparrow by Edward Poynter

Even in the midst of depicting highly charged passion, however, the neoteric imperative to show off one’s learning prevailed. Lesbia is a reference to Lesbos, an island off the east coast of what is now Turkey. For poets, though, Lesbos, in turn, refers to Sappho, a lyric romantic poetess who lived there in the 6th century BC and one of Catullus’ main inspirations. By placing this cultural reference center-stage, Catullus shows off his cleverness and places his own work within the tradition of love poetry.

Catullus moves beyond Sappho’s love poems, though. He is the first to depict love in a relationship as a dynamic movement of emotion rather than as a single static subject. And, whilst Sappho desired, but only from afar, Catullus and Lesbia have an actual relationship.

We experience the euphoria of their beginning in Poem 5:

Let’s live, my Lesbia, and let’s love

And those rumors of senile folks,

Against them, value one cent above.

Death and rebirth are nothing for days,

But when our brief light finally croaks,

On us night an endless slumber lays.

Kiss me thousands, then a hundred more,

Then add one thousand one hundred strokes,

And then a final fifty-five score.

Then, the many thousands we have coaxed,

We’ll disarray them, lest they’re declared

And open us to a spell evoked

By one who knows the kisses we shared.

(All translations done by the author.)

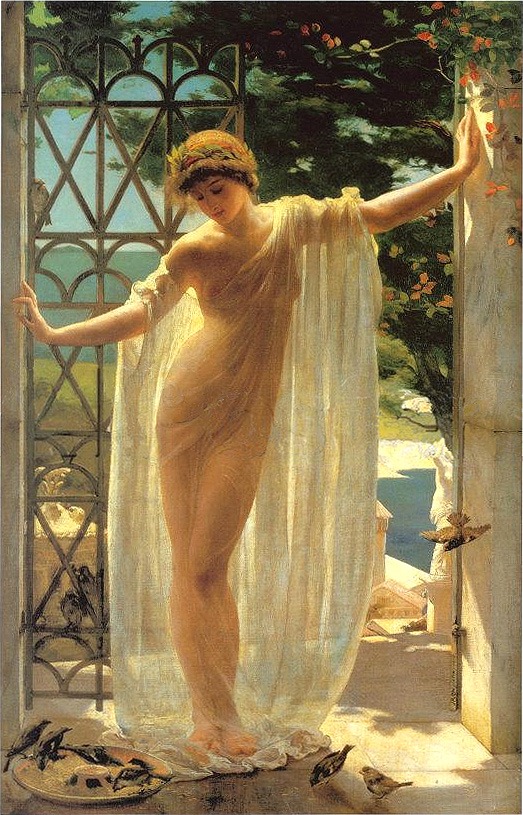

The Sparrow of Lesbia by Guillaume-Charles Brun

She swears to me she would not wed another,

Not even if Jupiter himself sought her.

But what a woman tells her lustful lover

Should be writ on the wind and the running water.

Lesbia by John Reinhard Weguelin

Thwarted in love and by love, Catullus plunges into the depths of despair in Poem 75:

My mind, Lesbia, your weight has brought down low

Until it split itself doing this duty,

It can’t wish you well, yet the best you could be,

Nor stop loving you, yet ill you could bestow.

By Poem 85 Catullus has been utterly crushed:

I hate and I love. “How do I manage this,” you may wonder…

Fucked if I know, but I feel it done and am torn asunder.

For such a short poem, it’s beautifully complex, showing off Catullus’ mastery as a poet. It begins with him actively doing things, namely hating and loving. It’s a paradoxical balance like the one found in 75, so, of course, someone has to ask how he does it. Then he fails and the whole poem moves into the passive. The hate and love he feels are done to him. Love is not a free surrender here, but a passion eating away at him. It is the purest distillation of the hopelessness youth feels before the waves of unknown and uncontrollable emotion, which is partly why Catullus has always attracted teenagers.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it set the foundations for future emo lyrics. Roman love poetry responded to Catullus and the effect trickled down ever after, reverberating in Bowie’s early song about spurned love “Letter to Hermione” and gnash’s “i hate u, i love u.” After a while, the original seems unoriginal.

The flip side to Catullus’ emo love poetry is his angry, more punk work. These invectives, the genre of poetry the Greeks and Romans used to verbally beat down someone, make up close to half of his work. Usually, they’re personal attacks against people exhibiting pretentiousness and boorishness who stand in as symbols for vulgar behavior in general. Witness the fury he flings at someone who stole his napkin in Poem 12:

Asinius Marrucinus, your left hand

Is up to no good as we drink and laugh:

It lifts napkins as they await demand.

You think this is witty? Get out! Don’t be daft!

It’s utterly tasteless and uncool.

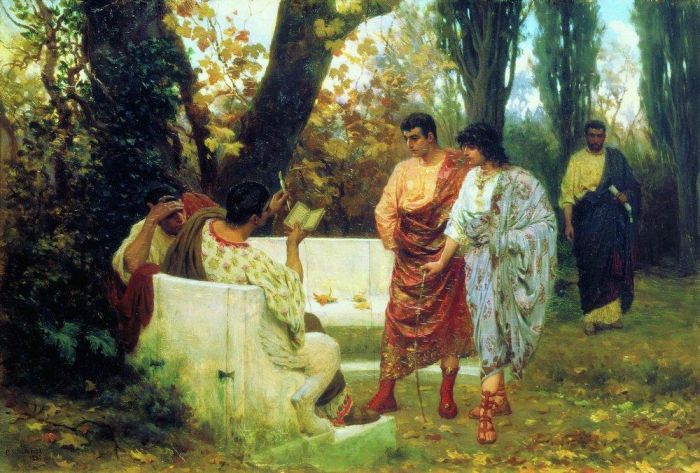

Catullus (second from left) reading to friends, by Stefan Bakałowicz

Or, as in Poem 84, he calls out someone’s pretentiousness for affecting an intellectual accent:

“Hwealth” he would say when he wanted to say

Wealth, and treachereagh for treachery.

Arrius thought himself striking this way,

Voicing treachereagh so cleverly.

I do believe his mum, uncle now free,

And his mum’s parents all spoke just like this!

But he’s been sent east, leaving our ears be

To hear these words spoken without amiss.

Nor later will they fear his spoken word

When faced with vile news from the plebeian:

The Ionian see has now been heard,

Not as Ionian, but Eee-oohh-nee-ahn.

Most of his other invectives follow this vein. Sometimes they’re humorous. Often they’re ruthless. But Catullus never punches down randomly. He targets people who betray themselves as artless or vulgar.

He himself is best known for his vulgarity, however. Lord Byron, who had dabbled in translating Catullus, mentions him in Don Juan, saying “Catullus scarcely has a decent poem.” The poem he probably had in mind when he penned that line is still knocking about today. Occasionally, an article like “A Latin Poem So Filthy That It Wasn’t Translated Until the 20th Century” or “Catullus still shocks 2,000 years on” appears. When you see them, you can be quite certain that they are talking about Poem 16:

I’ll fuck your ass and to you I’ll force-feed my cock,

Aurelius, Furius, my little sods,

You who’d derive me from my poetic stock,

Saying their sweetness springs from my shameless wads.

For while a pious poet ought to be pure

HIMSELF, nothing is needed of his verses;

Besides, with their wit and glamour they allure,

Only when sweet and shame one intersperses.

Then they become able to arouse an itch

— not in mere boys — but in these hairy men here

Who can’t even get their deadened groins to twitch.

But you who of my thousands kisses dear

HAVE READ, you’d give my masculinity a knock?!

I’ll fuck your ass and to you I’ll force-feed my cock.

It was upon being read that poem that my puerile obsession with Catullus began.

But this puerile obsession, mine and everyone else’s, obscures the ironic argument. The intimacy Catullus’ persona displays when despairing over Lesbia invites the reader to try to understand the poet as a person. The poems scream to be read as a confession. You can’t, though, and Catullus will fuck any who tries. But, of course, it’s the persona who says this so who can say how seriously one should take the threat?

Bust of Catullus in Sirmione, Lombardy, Italy (Picture Credit: Elliott Brown)

Another interpretation posited by Michael Broder in “Camping It Up in Ancient Rome: A Queer Take on Catullus 16” in The Huffington Post, is that Catullus is ridiculing the hyper-masculinity that defined Roman sexuality. For a Roman, to be a man is to sexually dominate the other, the gender of which was largely irrelevant, hence the repeated threats of rape. Even if Catullus were to follow through with it, though, he would still be the Catullus who wrote about his thousands of kisses. Broder goes on to compare the inner and outer audiences of this joke to those who’d go to drag queen performances. In the sixties, drag queens called themselves “female impersonators” to make the straight audience more comfortable, but everyone who knew them personally knew they go to the gay bar afterwards. Catullus’ joke blurs the line between whether he’s actually immoral or putting on a show. So again, we return to the issue of the persona.

Regardless of who the poet was, the persona of Catullus remains the original emo artist. The character Catullus created for his poems allowed for the expression of emotions at a previously unimaginable intensity and complexity. Catullus may be a mask, but the love and hate are felt all the same.