China’s Loose Canon

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

27/2/2021

Many people are familiar with the Western canon, those core works of literature, history, and philosophy that are considered essential to the study of the subject. In the West, students of literature read Shakespeare and Cervantes, students of history read Herodotus and Thucydides, and students of philosophy read Plato and Aristotle, amongst others. This canon is considered an integral part of Western civilization, and has shaped artists, thinkers, and statesmen for generations.

Yet few outside China know much about the Chinese canon, which is as rich and valuable as its Western counterpart.

In the field of literature, it includes what’s known as “the four great books,” The Water Margin, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, The Journey to the West, and Dream of the Red Chamber.

The Water Margin features 108 heroes who, renouncing a corrupt and unjust Song Dynasty, form a band of outlaws and live, Robin Hood-style, in a marsh, resisting the authorities, righting wrongs, and defending the weak in accordance with their own (extremely violent) code of honor. It explores the theme of a just insurgency, with the heroes choosing to serve “the will of heaven” over the Song rule of law.

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is a historical novel, following the breakup of the Han Dynasty into three warring kingdoms. It relates the battles, the gallantries, the intrigues and the strategies as the three kingdoms vie for supremacy. Its characters show strategic brilliance, nobility, and valor, but also hubris, stupidity, and self-destructive envy, in short, the full spectrum of human nature amidst triumph and disaster.

Scene from a 2010 Romance of the Three Kingdoms tv series

The Journey to the West is a fantastical account of the monk Tripitaka’s journey to bring Buddhism from India to China, in the company of an anarchic fighting monkey, a lustful pig demon, and a fearsome sand demon, and the adventures they have on the way, as they meet monsters, demons, and gods. The central theme of the comic novel is the tension between temptation and virtue, between passion and discipline, as the heroes strive (or fail) to live up to Buddhist ideals.

The greatest of the four, so great that it spawned its own discipline, Redology, is Dream of the Red Chamber. This novel follows the doomed romance of the protagonist Baoyu with his cousin Daiyu amidst the decline and revival of the illustrious Jia family. Its excellence lies in its execution, in its witty and spirited characters, in its colorful depiction of life inside a great house peopled by relatives and servants and the complex, shifting relations between them. It is a meditation on the meaning of life, as Baoyu is caught between his natural romanticism, the stern Confucianism of his father, and the Buddhist detachment born of suffering and enlightenment. Blurring the lines between reality and illusion, it is a bittersweet tribute to youth and youth’s end.

Scene from Dream of the Red Chamber, by Qing Dynasty artist Sun Wen

A novel sometimes called the fifth great book, but often denied that status because of its frequent and explicit depiction of sex, is The Golden Lotus. It follows the life of the beautiful Pan Jinlian, who murders her dwarf husband to elope with the notorious playboy Ximen Qing and become his fifth wife. The novel illustrates the lengths Pan Jinlian and the other women of Ximen Qing’s household go through to win and keep his favor. Lurid and irreverent, The Golden Lotus is known for its detailed portrayal of Chinese customs, and for its porn. Ok, mostly for its porn. But it’s good porn.

Pan Jinlian, played by Gan Tingting, in a 2011 tv series

In the field of history, the Records of the Grand Historian are widely regarded as the greatest classical work of history. Written by Sima Qian, a court official, who, after falling out of imperial favor, chose castration over death so he could finish writing his histories, the Records cover over 2,000 years of Chinese history. Depicting rulers with all their virtues and vices, it’s the primary means by which we know of many of them today.

The Chinese philosophical canon begins with Confucius. Far from the patron saint of Asian authoritarianism, as he is so often made out to be by opportunistic Asian dictators and clueless Western commentators, Confucius actually counseled balance, reciprocal obligations between ruler and ruled, and stubborn integrity in the face of unjust authority, along with filial piety.

Qing Dynasty painting depicting Confucius presenting Buddha to Laozi

Other canonical Chinese philosophers range from Mencius, who expanded on Confucius’ teachings, to the Hobbesian Han Feizi of the Legalist tradition, which advocated strict rules and harsh punishments to maintain social order, to the metaphysical Zhuangzi, who playfully blurred the distinction between reality and dreams, knowledge and ignorance, and life and death.

Perceptions of this canon changed through Chinese history. Novels were traditionally viewed with disdain, and deemed unworthy of serious study, but they were beloved by the general public, who often passed them on orally. From the time of the Tang Dynasty, scholars wrote commentaries on Sima Qian’s Records. Most of all, the Confucian texts were placed at the center of an education, as ambitious Chinese boys had to write essays on them in the all-important civil service examinations. Whilst only a small percentage of the population participated in these examinations, and the majority were illiterate, as with the great novels, Confucian philosophy spread through the masses orally.

With the overthrow of the last dynasty in the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and the New Culture Movement after that, however, the Chinese canon fell into disfavor, as it was associated with the “weak and backward past” that had left China at the mercy of Western powers.

The Communist takeover in 1949 saw this canon excised from public life. The tales of cavorting maidens and moonlit banquets were deemed decadent, the accounts of emperors and ministers and concubines were deemed counterrevolutionary, and Confucius was deemed the philosopher of reactionary feudalism. No longer were these things taught in schools or reenacted on the stage (although many parents continued to teach it to their children in private). Instead, Mao Zedong substituted his Little Red Book and revolutionary works like Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, along with the philosophy of Marx and Lenin. This came to a head with the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), when Red Guards declared war on “old ideas,” burned books en masse, many of them Chinese classics, and went so far as to desecrate Confucius’ tomb. Whilst the canon continued to be taught in schools in Taiwan and Hong Kong, for many years it seemed to vanish from the land of its birth.

The irony was that Mao himself had a great appreciation for the canon. Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who, with Richard Nixon, visited Mao in Beijing in 1972, described the chairman’s study thus: “Manuscripts lined bookshelves along every wall; books covered the table and the floor; it looked more like the retreat of a scholar than the audience room of the all-powerful leader of the world’s most populous nation.” Mao’s collection included classical Chinese poetry, The Water Margin, and even Dream of the Red Chamber, which he boasted of having read five times. What he enjoyed privately, he denied to everyone else.

Mao had a great appreciation for the Chinese canon: what he enjoyed privately, he denied to everyone else.

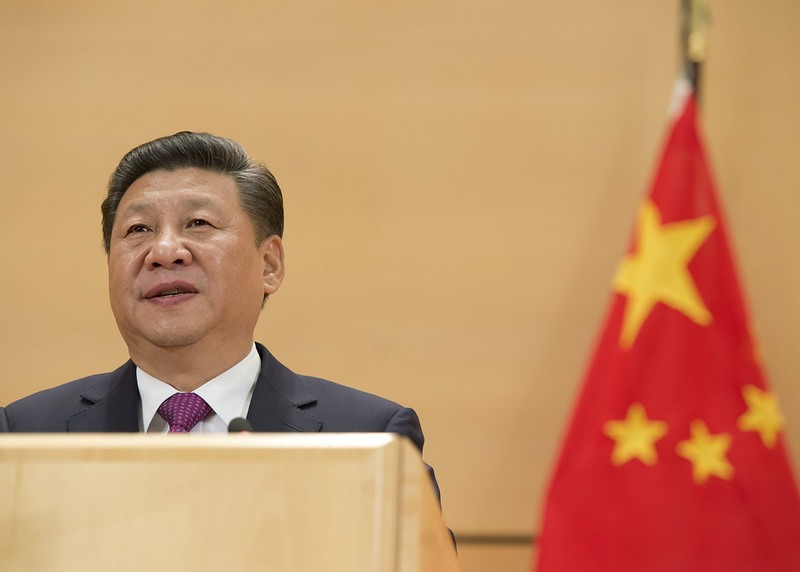

With the death of Mao and the end of the Cultural Revolution, however, the canon was slowly revived, and it began to be taught in schools again. Today, students in China learn the Chinese classics from early years all the way to university. Chinese President Xi Jinping laces his speeches with quotes by Mencius and Han Feizi, and in 2014 he made a pilgrimage to Confucius’ hometown in Qufu. “The classics should be set in students’ minds,” he said, during a visit to Beijing Normal University, “so they become the genes of Chinese national culture.”

Why this renewed enthusiasm for the canon?

Many point to the enormous changes Chinese society has undergone since Deng Xiaoping began opening and reforming the country in 1978. As fortunes rose with the embrace of capitalism, commitment to Communist values dwindled, such that few Chinese today take Communist principles seriously. Chinese policymakers fear a populace driven only by materialism, obsessed with making money at any price, and without a moral compass.

“As communism gradually [loses] its luster, China finds herself trapped in a moral vacuum,” said Kwok Ching Chow, former Professor of Chinese at Hong Kong Baptist University. “It is only logical that the Chinese government would turn back to traditional culture, which is rich in morals and ethics, for rescue.”

The absence of any genuine loyalty to Chinese Communism also leaves many people without a strong sense of national identity. Restoring the canon, therefore, also serves a unifying function, explained Bryan Van Norden, Chair Professor in Philosophy at Wuhan University, and author of Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto. “Xi is trying to reintroduce the traditional canon […] to give people a group identity as ‘Chinese,’” he said.

“Xi is trying to reintroduce the traditional canon […] to give people a group identity as ‘Chinese.’”

It’s a logical decision, and Chinese should certainly cheer the return of their canon to its proper place, but this move presents risks of its own for the Chinese Communist Party.

The Party, after all, is the definitive authority on Chinese Communist doctrine, but the same cannot be said of Chinese canonical works, which can be interpreted in different ways by people.

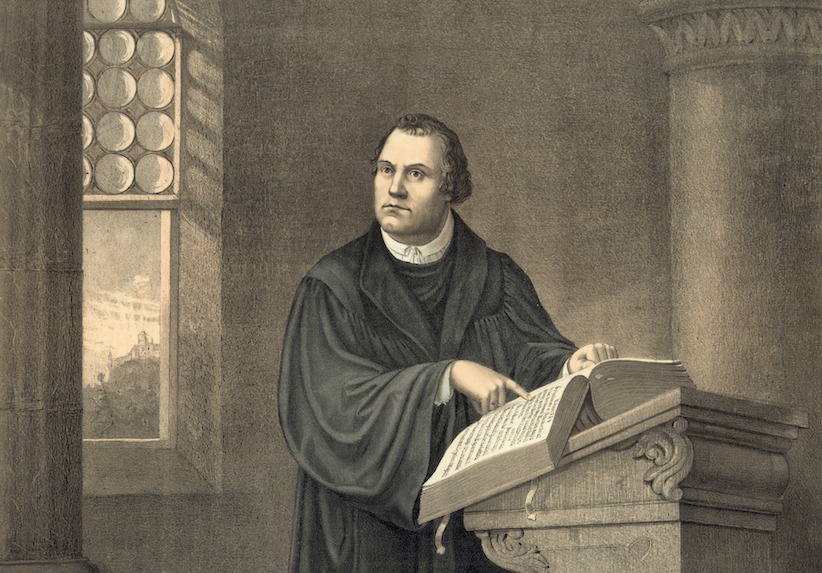

A parallel here is the Reformation. For centuries, the Pope, seen as God’s representative on Earth, was the ultimate authority on Christianity, and salvation could only be obtained through the priests and churches he sanctioned. When Martin Luther began preaching that the last word on Christianity was not the Pope in Rome, but the Bible, which could be read and interpreted by anyone, he caused a revolt against the Vatican and a schism within the faith.

Antique print of Martin Luther in his study in Wartburg Castle in Eisenach

Similarly, if the source of values in China is no longer the Chinese Communist Party, but the Chinese canon, which anyone can read and interpret for himself, what might this mean for the Party’s authority?

And how might Chinese people interpret these canonical works? Will they see the revolutionary Chinese Communist Party as the virtuous rebels in The Water Margin, or more like the corrupt and unjust Song Dynasty they resisted? Will they see Xi Jinping as one of the benevolent emperors in Sima Qian’s histories, or more like the tyrant Qin Shi Huang? Will they see him as the kind of worthy ruler Confucius counseled serving, or an unworthy one that should be scorned?

“Xi hopes [to revive the canon] so that he and the Communist Party can maintain strict control over the Chinese people,” said Van Norden. “The danger, though, is that generations of intellectuals have found in these same texts the resources to challenge the status quo. Confucius and Mencius were both insistent critics of the governments of their eras. Perhaps Xi is unleashing forces he may not be able to control?”

Perhaps that’s what Chinese authorities feared when in 2011 they surreptitiously removed the 31-foot statue of Confucius from near Tiananmen Square – just four months after they had unveiled it there.

A loose canon like China’s is an uncertain tool for social control.

This story originally appeared in China-US Focus at this link.

Appendix: The Chinese Canon

The Chinese canon includes the following.

Literature

Novels

The Four Great Books:

The Water Margin by Shi Naian

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong

Journey to the West

Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin and Gao E

The Golden Lotus

The Scholars by Wu Jingzi

Short stories

Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio by Pu Songling

Plays

The Story of the Western Wing by Wang Shifu

The Peony Pavilion by Tang Xianzu

The Palace of Eternal Life by Hong Sheng

The Peach Blossom Fan by Kong Shangren

Poetry

Li Bai

Du Fu

The Songs of the South

Wen Xuan

History

Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian

Philosophy

Confucian

Confucius:

The Analects

The Great Learning

The Doctrine of the Mean

Mencius

The Five Classics:

The Classic of Poetry

The Book of Documents

The Book of Rites

The I Ching

The Spring and Autumn Annals

Legalist

Han Feizi

Buddhist

The Platform Sutra by Huineng

Daoist

Daodejing by Laozi

Zhuangzi