Common People Are Not Stupid

By Julien Oeuillet

Staff Writer

30/8/2021

In Good Will Hunting (1997), Matt Damon plays Will Hunting (far right), a working-class genius

The world of politics, media, academia, and art is very incestuous. Everyone sticks together, befriends each other, marries each other. The ivory tower is also an echo chamber where we are constantly told how special we are, and reminded not to despise those outside our coterie. The prevailing attitude towards the working-class is benevolent condescension, characterized by the elitist fear of being elitist, a misguided belief that you need to hide your brains in their presence because they have none. Populist electoral victories in recent years are misread as a sign of ignorance, and so is the mindlessness of profitable mass media.

Nothing could be further from the truth. In my 20 years in journalism, I have desperately defended the notion that common people are not stupid, and that we should treat the public as if it were intelligent and hungry for deep and worldly content.

I once accompanied a friend of mine – an academic historian, author, and publisher – to the village where he grew up, which is located in the province of Hainault, one of the poorest parts of Belgium, deep in the countryside. When we got there, he strode casually into a shady bar, ordered the heaviest beer, and chatted with folks who were at best manual workers and at worst chronically unemployed. He fit right in. In the old Walloon dialect, a patron said of my friend “Il a sti à skole!” – “He has been to school!” – a way for uneducated locals to compliment someone for their education. My friend listened to the crowd. He was not a professor returning to lecture the villagers; on the contrary, he was learning from them. They knew everything of local folklore, of what happened in the region from medieval times to the previous weekend. They were educating him. There was no envy, no resentment, and no condescension. These people may have been crude, but they were not dumb.

Actually, it’s rare for me to have an academic as a friend, since I generally shun personal bonds with people from this industry, and from my own. This is because I find these worlds toxic, and because the intelligentsia are rarely very interesting in private. I prefer to find company and inspiration in the marginal, working-class roots I come from.

I was born of two blue-collar families. As a child, I lived in Marseilles, a harbor city in southern France, where my forefathers emptied trucks and welded boats. As a teenager, I lived in Limay, a “red suburb” in Paris, so called because of how unionized the workers living there were. I grew up amongst the rich culture and the sharp eyes of the paupers. When I write or make films, I remember that this world is theirs, too.

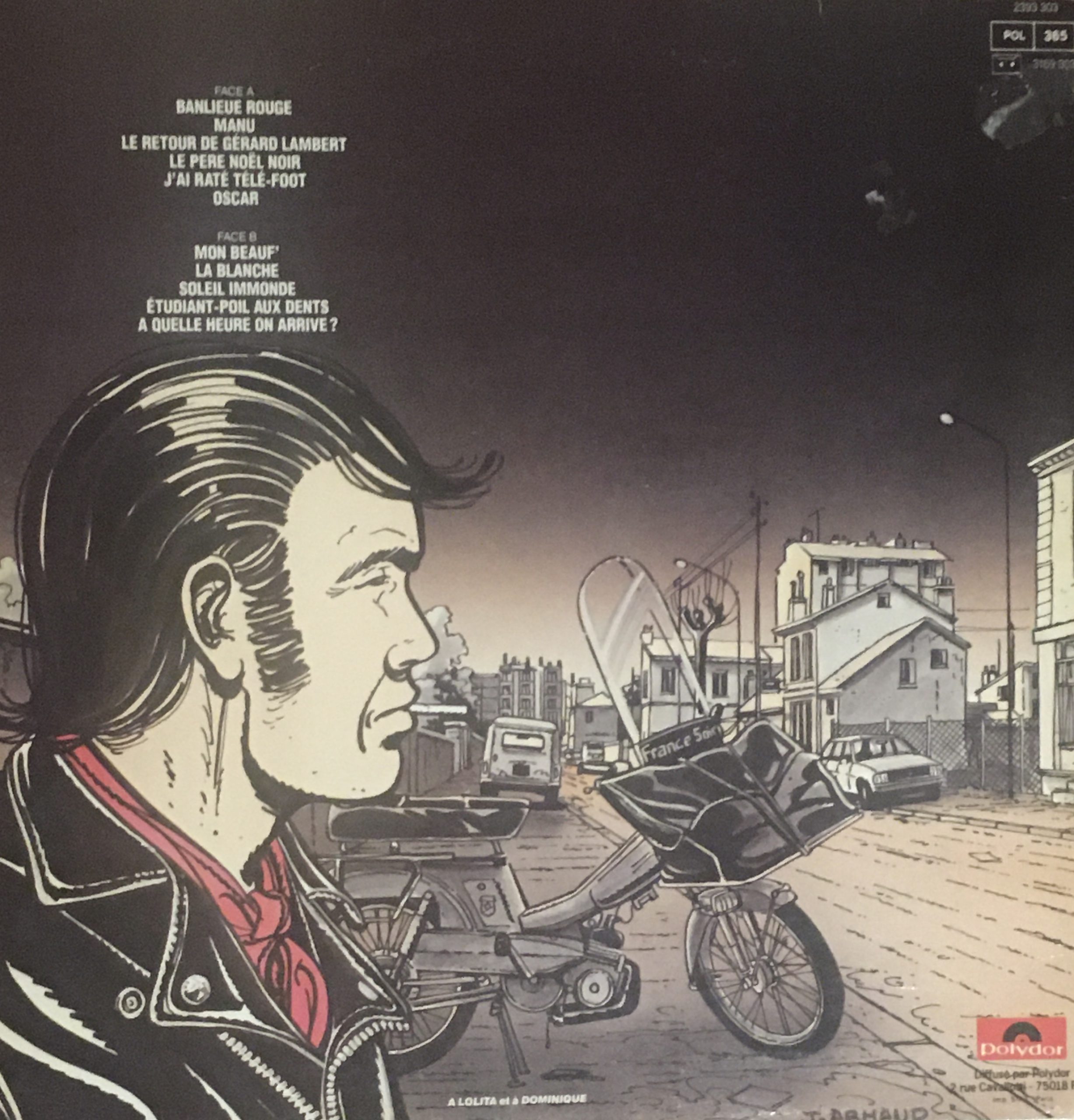

The red suburbs (“banlieue rouge”), illustrated on the cover art of French singer Renaud’s 1981 album (Picture Credit: Jacques Armand)

If you finished primary school, you are educated enough. It gives you the basic tools for a rich life: you learned to read, so you can choose to spend your time reading to gain knowledge. People from every social class yearn to elevate themselves. Standing at the front door of my father’s warehouse, the smell of gasoline thick in the air, with men, half of them migrants, whose arms were as thick as my legs, holding rolled cigarettes in their calloused hands, we’d discuss history and sociology. I would listen to them talk about their families, the history of their town, the politics of their region, and the direction of the country. Centuries of civilization flow through their brain cells, the same as in anyone else’s, and their ideas are no less deep for being expressed in simpler language and with a thicker accent. I know mechanics who read all about free jazz, removalists who binge documentaries on ancient cultures, woodworkers with a fascination for Scandinavia, menial clerks who know a Lempicka from a Klimt, and a truck driver who would expound on various forms of gothic architecture (he saw new specimens to point out on each new road he took). These people simply used the tools they learned in primary school to better themselves. They are not rare or exceptional. They crave edification as much as anyone.

People from every social class yearn to elevate themselves.

And yet, so often in my career in media I ran into people who constantly underestimated the public. I always wanted to create content that was accessible to all viewers without patronizing them. But producers and broadcasters constantly tried to water-down the documentaries I directed because they were “too intellectual” (aren’t documentaries meant to be intellectual?). These people were all fond of flaunting their long years of experience, and of reminding me that their academic penises were bigger than mine, that their ancestors did not toil in warehouses like mine did, but were already active in the world of letters before the television was invented. You’re too serious, they said, not fun enough, you need to add something more popular, dumb it down, who cares about these countries and people you seem to think are interesting? Turned out a lot of people cared. Although I spent much more time fighting for my documentaries to be aired than making them in the first place, once they were broadcasted, audiences seemed to enjoy them, and they got higher than average ratings. This is not because I am an awesome filmmaker, rather, it’s because I was right not to underestimate the audience’s intellect. Just like with my writing, I was not shy to talk about obscure places, people, historical periods, and ideas, yet the audience I attracted was obviously far larger than the niche intellectual circles that are supposedly the only ones who care for such highbrow fare. Everyone in this industry could make the conscious choice not to lower their expectations and to challenge their readers and viewers, including those who hail from the working-class. These people will appreciate it – and I know because, at heart, I am still one of them.

Shipping containers as art, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (Picture Credit: Evelyn Chai)

I always felt alienated from elites and intellectuals, not least because of how surprisingly shallow they can be. They often lack the self-awareness to realize their limitations. They consider themselves as the guardians of the temple of knowledge, forgetting that anyone who can read can spend his free time reading books, just as any hyper-educated person can squander his time with frivolities. They view enlightenment and the life of the mind as something reserved for the elect, not something that all people aspire to – and can reach.

Elites and intellectuals often lack the self-awareness to realize their limitations.

This is how we ended up with such a wide rift between those who create content and their audience. This is how supposedly progressive people lost those they were supposed to serve. This is how journalists became marketers and came to believe they would get more clicks if they talked about stupid things for stupid people. This is how those who were supposed to spread knowledge betrayed their mission in favor of an empty charade that the masses are too clever to fall for.

Because, really, us common people are not stupid.