Consuming the Consumer: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

By Felix Behr

Staff Writer

6/8/2019

Google Home personal assistant (Picture Credit: NDB Photos)

At Def Con 25 in 2017, one of the world’s largest hacking and cybersecurity conventions, Svea Eckert, a German tech journalist revealed the browsing history of a German politician in the audience. She dredged up details like the fact that she was an early riser, that she’d searched for medication, Tebonin, and that on the first of August, she’d checked her bank account.

“You can see everything,” the politician exclaimed. “Shit!”

Many might think Eckert must have hacked her computer. But Eckert didn’t need to – she just bought the data. Posing as an AI startup in Tel Aviv, her team could buy the data of 3 million German citizens from various companies that happened to store it and serve as data brokers.

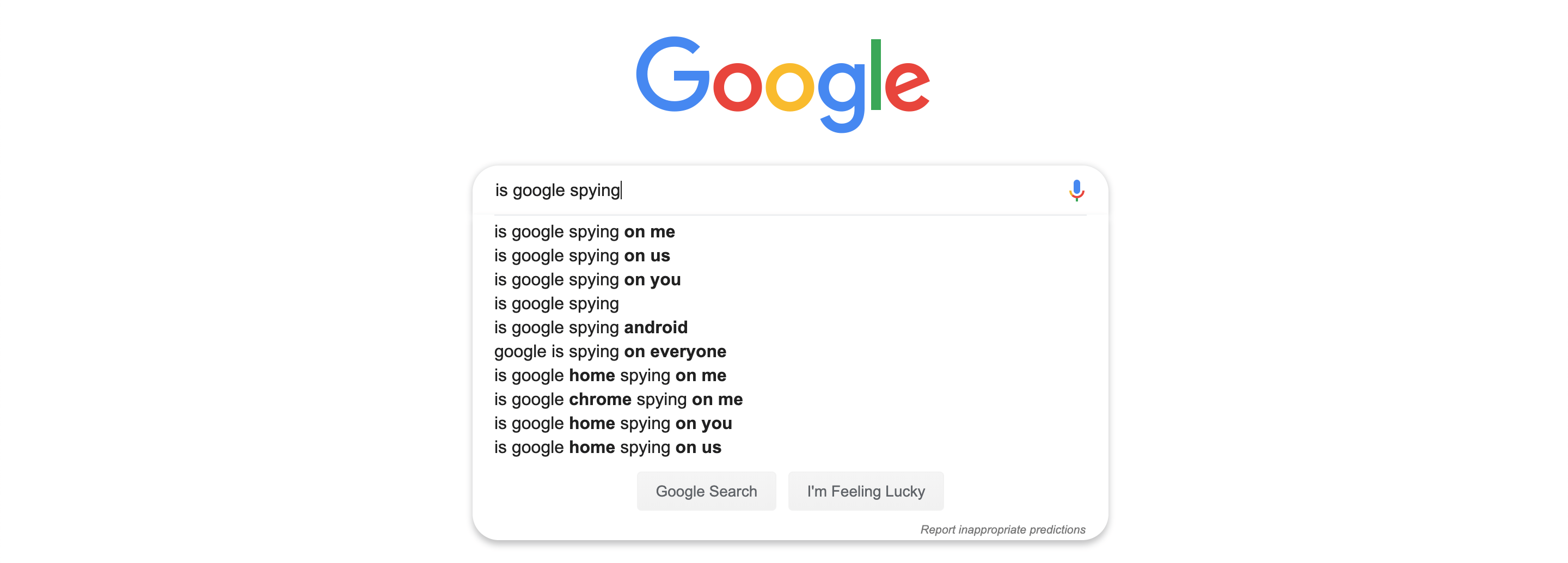

This should no longer be surprising. We all know the maxim of the internet that goes “If the service is free, you are the product.” We hear it, nod, then return to Google to search for the cheapest stuff.

We all know the maxim of the internet that goes “If the service is free, you are the product.” We hear it, nod, then return to Google to search for the cheapest stuff.

The extraction of data from unwitting users is not a market on the internet but the market of the internet. The logic remains invisible to us by both overexposure and design. However, Shoshana Zuboff, former Charles Edward Wilson Professor at Harvard Business School, spills considerable ink over the practice in her new book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power.

Zuboff’s account of surveillance capitalism ambles from Google’s commodification of its search function to Google Maps to Pokémon Go. In the late 90s and early 2000s, Google was merely a search engine with decent venture investment. It also faced the fallout from the bursting of the dot-com bubble. In the midst of this turmoil its founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, abandoned their aversion to advertising and tasked their AdWords team with overhauling the whole process, replacing the original model in which companies would choose which searches would lead to their product or service with one in which Google would do so itself.

Google had long tracked its users, of course, including their location, their searches, and the time they spent looking at results. “Every action a user performs is considered a signal to be analyzed and fed back into the system,” Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist explained. Previously, however, Google would just use this data to better match people with their needs. It would see a certain article had a higher engagement and promote it accordingly (though companies could pay to have an ad for their product top the list of relevant search results).

Google’s pivot, which Zuboff credits with spawning surveillance capitalism, took all the data created by the user and then continuously tracked the user to assemble unique profiles. In fact, Google did more than merely assemble the digital exhaust into recognizable shapes. It increased its data capturing abilities and strengthened its ability to infer connections, like the probability that someone researching prostate cancer would be an older man. Google began to sell these profiles on a hidden market, promising to predict our actions and influence our decisions by transforming our experience of the internet.

Google’s transformation saw the company abandon its recycling of data for the benefit of its users for a logic of accumulation to appease advertisers and investors. The data that fuelled Google’s search functions was more than necessary to run an efficient search system. The goal, instead, was a total understanding of its users to direct them to the people actually paying Google’s bills. This pushed Google, Facebook, and the companies that followed to expand these practices as far as they could, turning every interaction with a device into something to be sold to a third party.

Google and Facebook have turned every interaction with a device into something to be sold to a third party.

The commodification of our digital existence is now a central feature of internet. We have internalized it and rarely notice its daily infringements into our privacy. Compare Edward Snowden’s 2013 disclosures of the US government’s global surveillance to Google’s privacy infringements as it was compiling Street View – the program that allows us to move through recreated panoramas of areas stored in Google Maps – between 2008 and 2010. As the Google cars paraded through the streets they “accidentally” siphoned data from the houses they passed and “mistakenly” kept it, only admitting these “errors” when pressed. They also caught the images of the people they passed, only deleting them when those individuals demanded it. Facebook’s various scandals also periodically result in an outcry. This anger, though, soon flagged and will flag again, unlike our campaigns against federal uses of surveillance. We are weirdly fine with corporate invasions of privacy even as we fight off government ones.

We are weirdly fine with corporate invasions of privacy even as we fight off government ones.

“Yes,” Zuboff admitted, “when we leave our home we know that we will be seen, but we expect to be seen by one another in spaces we choose. Instead, it’s all impersonal spectacle now. My house, my street, my neighborhood, my favorite cafe: each is redefined as a living tourist brochure, surveillance target, and strip mine, an object for universal inspection and commercial expropriation.” With this move, Google and other practitioners of surveillance capitalism extended their reach beyond the digital world into the physical one.

Of course, the ever-increasing presence of internet-related devices and apps in our lives blurs the lines between digital and physical space. In a recent piece for The Baffler titled “I Feel Better Now,” for instance, James Bittle explored the surprisingly large market of mental health apps, something one would normally consider intrinsically personal and intimate. Since these apps regulate their user’s mental health, they track a range of details including the drugs the user takes, the food they eat, and, of course, their moods. After all, without all that information, the app would be rather useless.

Bittle’s piece, though, recognizes that the industry doesn’t make money from subscriptions alone. It shares data instead, processing users’ experiences to make predictions on what they might want in the future.

Zuboff spelled out her problem with surveillance capitalism thus:

The big pattern here is one of subordination and hierarchy, in which earlier reciprocities between the firm and its users are subordinated to the derivative project of our [behavioral data that can be used beyond service improvement] captured for others’ aims. We are no longer the subjects of value realization. Nor are we, as some have insisted, the “product” of Google’s sales. Instead, we are the objects from which raw materials are extracted and expropriated for Google’s prediction factories. Predictions about our behaviors are Google’s products, and they are sold to its actual customers but not to us. We are the means to the others’ ends.

Though extensively detailed, Zuboff’s analysis fails to convince when it limply gestures to a “rogue force” as the cause of surveillance capitalism rather than a logical continuation of capitalism into the information age. While companies can and in many cases do benefit the community, public spirit and regard for the common man isn’t at the heart of capitalism, profit is – and wherever companies can extract profit, many will.

Surveillance capitalism also manages to capture one of the predominant ironies of the information age: the inability to know while all knowledge is supposed to be at our disposal. Surveillance is a one-way mirror – we don’t know how our watchers operate. For many, this isn’t an issue but a reasonable condition for devices they eagerly welcome. Smart home devices, digital assistants, and the internet of things in general require constant surveillance. These machines sit, waiting for the correct “wake word” like “Alexa” and “Ok, Google.” This, of course, means that the microphone in a smart home has to listen to everything, otherwise it wouldn’t be able to pick up on the wake words. Surveillance has been normalized to the degree that we will willingly bug ourselves for corporations. Or, as Alex Cranz of Gizmodo put it, “Sorry George Orwell. I don’t give a fuck.”

Surveillance has been normalized to the degree that we will willingly bug ourselves for corporations. Or, as Alex Cranz of Gizmodo put it, “Sorry George Orwell. I don’t give a fuck.”

To be fair, Google and Amazon publicly stated that they don’t record conversations that occur before the wake word is uttered. But even if we believe they aren’t extracting every byte of data they possibly could, which for me would be a tall order, the push to voice-activated technology in the places where we are the least guarded still offers new reams of data to process. If Bittle’s mental health apps merely asked for intimate data, voice-activated assistants would extrapolate it from one’s voice.

On 30th April, Amazon filed a patent for systems and methods that could identify emotions and mental state based off of audio input. While the idea is fine per se — after all, if you are going to talk to your computer, it might as well respond appropriately — its connection to Amazon brings us back to surveillance capitalism. The authors of the patent point to how data gathered from wearable devices are used to diagnose and prevent medical conditions. They point to this, though, only after explaining in greater detail how such data helps with personalization:

[Data] that is produced by computing devices is being used in a plethora of ways, many of which include personalizing and/or targeting decisions, information, predictions and the like for users, based in part on data generated by or about each user. For example, data generated by a user’s computing device or devices (e.g., mobile device, wearable device), such as transaction information, location information, and the like can be used to identify and/or infer that user’s preferred shopping times, days, stores, price points, and more. In turn, the identified and/or inferred information can be used to deliver targeted or personalized coupons, sales, and promotions, particularly at times or locations most proximate to the user’s preferences.

By including this in the background section of the patent, Amazon indicated that the purpose of these algorithms will be to influence people’s purchasing decisions based off of their voice. While the tone may package the details as efficient customer service, the gathering of data for the expressed purpose of inferring their future actions falls directly into the mode of surveillance capitalism. A cynical person could easily imagine Amazon plying people with promotions when they’re at their most vulnerable.

A cynical person could easily imagine Amazon plying people with promotions when they’re at their most vulnerable.

This kind of surveillance is carried out with an air of indifference. Most companies interest themselves with the search for Tebonin, not the person searching for it. They see a bundle of data, not the person whose existence they’ve translated into data.

There’s very little an individual can do. Simply quitting is not an option, as these services have woven themselves into our day-to-day lives (just imagine the internet without Google). Rather, surveillance capitalism will only be curtailed by stronger regulations like the EU’s GDPR. But while attempts to legislate data and privacy protections exist, winning the culture war will prove more difficult. Implementing regulations requires a public willing to sacrifice the convenience of the technologies offered for the sake of privacy.