Creepypastas: The Monsters We Make

By Gurwinder Bhogal

Staff Writer

30/10/2019

Beware the Slender Man

One could be forgiven for thinking that campfire tales of ghouls and ghosts were born of ignorance, and that they would therefore diminish with the advent of the Information Age. In fact, the internet spawned a whole new form of spook story — the creepypasta — and made it go viral. Thus, in our rationalist age, horror folklore has become a greater part of civilization than it ever was before.

But what does it tell us about ourselves? Creepypasta is crowdsourced horror folklore, so it has much to say about society’s deepest fears. But the story behind creepypasta also illuminates other, far darker aspects of our nature.

The term “creepypasta” is a bastardization of “copypasta,” internet slang for a piece of text that prompts people to copy and paste it across the internet. Creepypasta is basically copypasta that prompts people to copy and paste it in fear (or in the hope of causing fear). It is essentially horror fiction, but distinguished from conventional stories primarily in that it is open-source. It usually has no listed author, copyright, or publisher. All that is required for its dissemination is a few clicks of a mouse, and anyone is free to amend the text. Since creepypastas have no gatekeepers except the community, they live and die purely by the degree to which they are copied and pasted. Creepypasta, then, is memetic horror; the weakest are forgotten and the best reproduced to become internet folklore.

The appeal of creepypasta is best understood by its most viral examples, and few creepypastas have gone as viral as those centered around one bogeyman in particular: Slender Man.

The monster was born on June 10, 2009, on the Something Awful message board, as an entry in a Photoshop contest. Its creator, Eric Knudsen, posted two black-and-white photographs of children and an elongated figure in a business suit. The photos were accompanied by eerie captions describing the mysterious circumstances in which they were discovered.

One of the two original Slender Man photos. The accompanying quote read: “We didn’t want to go, we didn’t want to kill them, but its persistent silence and outstretched arms horrified and comforted us at the same time.”

Other posters soon began elaborating on these captions, adding their own details. The most compelling details were copied and pasted across the internet, forming a mythos around the character. Few details about Slender Man remained constant from story to story — sometimes it killed children, sometimes it corrupted children into killers — but the inevitable contradictions that arose between individual tales, rather than weaken the legend, only added to its mystique. Soon, Slender Man was viral; school kids were sharing stories about it on the playground, adults were dressing as it for Halloween, and it had become the star of numerous video games and Hollywood movies.

But what is it about this monster that allowed it to so brazenly intrude into the mainstream, where others had been unable to tread? It is, after all, hardly an original creation, being reminiscent of earlier creepypasta bogeymen such as the Japanese Kunekune, another gangly pale-faced entity that causes insanity.

Shira Chess, a media studies professor and author of a book about Slender Man, believes the creature draws on modern anxieties like millennial distrust of the establishment. She points to Slender Man’s appearance — faceless and suited, like the archetypal bureaucrat — and emphasizes that the creature became prominent shortly after the 2008 financial crisis, when trust in the establishment had reached a new nadir.

But this explanation seems too political to be a significant basis for something as primal and universal as horror. A more fundamental explanation is that Slender Man’s appeal lies chiefly in its vagueness, something jarring in an age of information overload, like a sudden silence breaking hours of cacophony. Slender Man is an enigma, but it is also, like its own featureless face, a blank slate, allowing people to project whatever anxieties they may have onto it. Thus, if one person’s take on Slender Man doesn’t scare you, there are always others. Slender Man is an ad hoc nightmare, a jack-of-all-dreads.

If one person’s take on Slender Man doesn’t scare you, there are always others. Slender Man is an ad hoc nightmare, a jack-of-all-dreads.

But if Slender Man’s blank face is a mirror, reflecting whatever we fear most, then what fear does it reflect most? What are the deepest and most common fears of our age? Slender Man’s few canonical traits give us an idea of some primal human fears – its targeting of children, for instance. But discovering the fears that are most peculiar to our age requires an analysis of the creepypasta genre as a whole.

Unlike conventional horror stories, creepypastas are written for the internet, so it’s no surprise that the most common setting for such tales is the web. Some are in fact written entirely as online conversations, like Annie96 is Typing…, which takes the form of a WhatsApp conversation, cleverly building suspense by interspersing messages with “X is typing…” notifications, and concluding with a wicked ambiguity.

The appeal of online chats as a format of creepypasta lies in their familiarity, which lends a certain authenticity and, more importantly, a sense of banality. If fantasy and science-fiction are about the intrusion of familiar elements into the otherworldly, horror is about the intrusion of otherworldly elements into the familiar. And what could be more familiar in the age of social media than a WhatsApp conversation or message board discussion? It lulls us into a false sense of security, allowing the inevitable horror to hit harder.

This is not to suggest that we equate the internet with safety; many of the scares in creepypastas are based on our anxieties about the web. “Annie96 is Typing…” plays on the fear that we can never be sure who we are talking to online. My Dead Girlfriend Keeps Messaging Me on Facebook elicits similar fears, but adds the dread of online stalking and harassment. Satellite Images, about a digital specter haunting a man through Google Maps, doubles as a metaphor for our lack of privacy. Annora Petrova, which takes the form of an email about a spooky Wikipedia page, evokes fears of online shaming and “cancellation.” Normal Porn For Normal People, a disturbingly plausible legend about a nightmarish porn website, indulges fears of what depravities may lie in the depths of the Dark Web (and the human subconscious).

Many of the scares in creepypastas are based on our anxieties about the web.

One of the most prominent fears of the Information Age is, well, information. The ubiquity of media constantly streaming out of electronic screens and permeating our lives brings with it a heightened fear of data that could corrupt us in some way, like a computer virus. Dangerous knowledge is not a new fear, being prominent in the works of H. P. Lovecraft for instance, but it has become one of the premier sources of horror in the creepypasta, taking advantage of the format’s memetic nature.

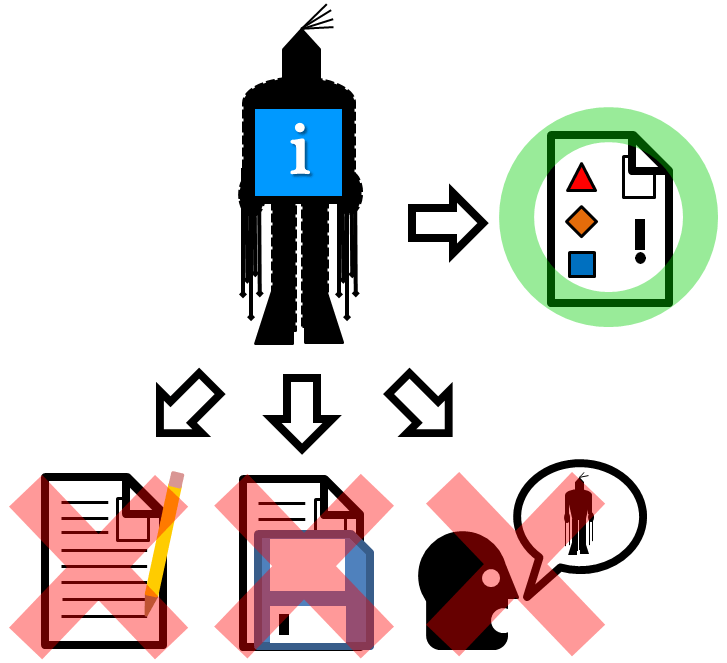

The hazardous information in Smiledog.jpg is a cursed image file that brings harm to those who view it unless they email it to others. In Funnymouth the hazard is a barely literate social media account that is also a mind-virus, turning those who engage with it into copies of it (possibly a metaphor for the online troll). Perhaps the most creative use of the “dangerous knowledge” trope is SCP-2521, a tale told in pictograms, which explain that there is a monster that will seize anything written about it, and kidnap anyone who mentions it (the monster doesn’t understand pictograms, though).

Pictogram from SCP-2521 explaining that the only safe way to discuss the monster is with pictograms

A common way that information poses a threat in creepypasta is by virtue of it being a “thoughtform:” something that becomes real through the power of will. Tulpa, which takes its title from a Tibetan legend of an entity created by thought, tells of a monster dreamed into existence by the narrator. Wake Up is a brief work of metafiction in which belief in a terrible fate can lead one to experience it. The most famous thoughtform in online folklore is probably Roko’s Basilisk, a hypothetical godlike AI created in the future, which will reach back in time and torture anyone who could conceive of it but didn’t help create it (including you, now that you know of it). The true horror in this thought experiment comes from the idea that if enough people know about the Basilisk, some might become terrified enough to actually create it.

A common way information poses a threat in creepypasta is by virtue of it being a “thoughtform:” something that becomes real through the power of will.

Thoughtforms reflect fears of a world where information has the impact of matter and the lines between the real and virtual become ever more blurred. But their appeal as a storytelling conceit probably lies chiefly in their capacity for “meta-horror,” that is to say that the very act of reading about a thoughtform becomes a ritual to summon it, giving the reader a sense of peril that leaps off the screen and into the real world.

One of the legends surrounding Slender Man is the Tulpa Effect, a theory that began to circulate around online forums in 2011, and even formed the basis of a YouTube series, about how with enough focus Slender Man could be willed into existence.

It is this legend of the monster that makes the incident at Waukesha, Wisconsin so disturbing.

In the summer of 2014, at the height of Slender Man’s popularity, two 12-year-old girls, Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser, lured their friend Payton Leutner into the woods, and during a game of hide-and-seek they ambushed her, pinned her down, and stabbed her 19 times.

When the police apprehended them, they claimed they feared Slender Man would harm their families unless they appeased it — by murdering their friend — after which they would serve the entity forever in a mansion in the woods.

Except, Weier was not actually convinced of the existence of Slender Man. On the day of the stabbing she admitted of the entity, “He is a work of fiction.” The testimony the girls later gave suggests an even more chilling explanation than their initial one: They did not carry out the attack simply because they believed Slender Man was real. They did it because they wanted it to be real. The stabbing seems to have been a desperate attempt by the girls to escape the confines of reality for the fantasy of horror — even if doing so required that they themselves become the monsters.

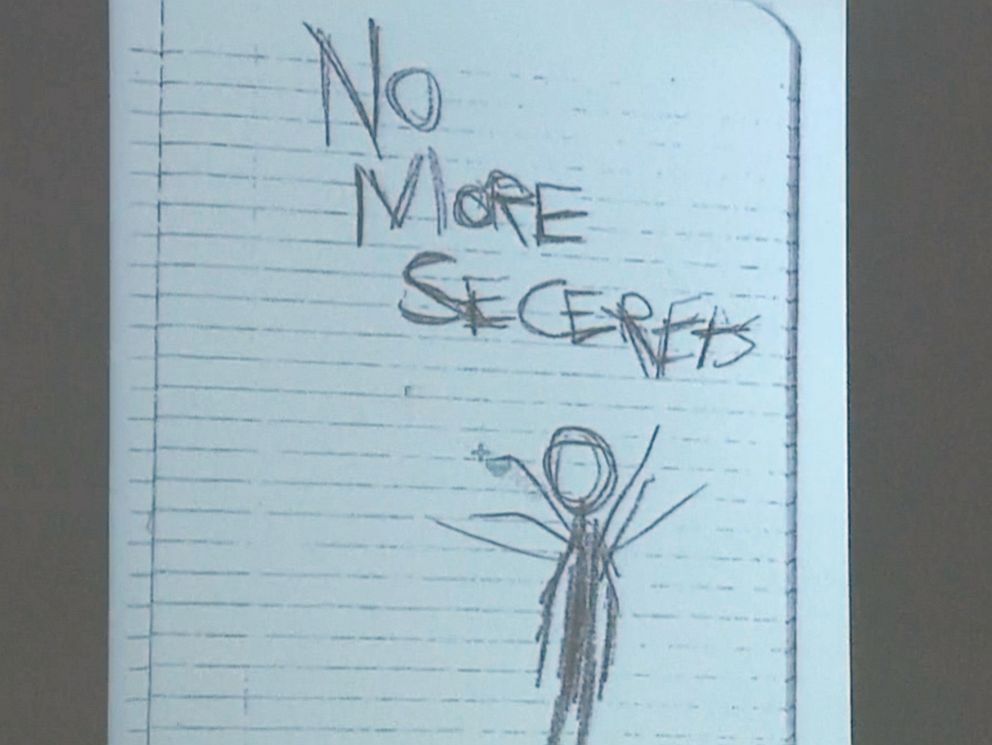

One of many Slender Man drawings from Morgan Geyser’s bedroom

The fact that fantasies of Slender Man caused the materialization of one of its defining traits — its corruption of children into knife-wielding maniacs — give a degree of credence to the concept of thoughtforms and the Tulpa Effect. Monsters like Slender Man may not technically be real, but they can exert enough influence over our minds to at times become virtually real.

Monsters like Slender Man may not technically be real, but they can exert enough influence over our minds to at times become virtually real.

Fortunately, Slender Man’s influence on the public consciousness has since waned. It was eventually defeated, not by a splash of holy water or by uttering its true name, but by copyright issues. The monster in the business suit was killed by red tape.

From around 2011, as online horror folklore began to enter the mainstream, market forces came into play, leading to the gradual commodification of creepypasta. By 2014, it was no longer defined by its intimately gossipy writing, or its collaborative open-source nature, or its spectrally anonymous authors. Now it was all about showing what a skilled writer you were and crafting a satisfying story arc, something that could be marketed, sold, and protected as intellectual property.

Due to interest from publishers and movie studios, some of the more elaborate works of digital horror folklore (usually from Reddit’s NoSleep subreddit) were reclaimed from the internet by their original authors to be developed into novels or movies. Slender Man was copyrighted by Knudsen and the media rights were seized by various companies, severely restricting the legend’s ability to spread across the Internet.

This problem was compounded by the fact that the attempts to turn Slender Man into a Hollywood franchise were quickly sunk by bad reviews and poor box office showings, which is unsurprising given that the entity was created to exist in grainy 240p video and snippets of text on obscure message boards, not 50 foot HD screens where every last detail could be scrutinized.

Although commercialization sterilized the virality of Slender Man, the entity’s mutated essence lived on in other legends that survived the great commodification, legends that would bring its terror to new heights.

In the summer of 2016, rumors of an online game called the Blue Whale Challenge began to circulate on Russian message boards. The challenge was apparently set by an anonymous “administrator” to a juvenile participant via social media, and required the participant to complete a series of daily tasks, which began innocuously (e.g. watch a horror movie) but gradually became more extreme, culminating in a command to commit suicide.

It is not known precisely how the story around this game came to be, but, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it is generally assumed that it was initially nothing more than an urban legend. Unfortunately, the legend was soon picked up by sensationalist newspapers who reported it as fact, fear of the game went viral, and several people took it upon themselves to become “administrators” of the game, making it a reality. Psychology dropout Philip Budeikin, postman Ilya Sidorov, and financial analyst Nikita Nearonov all admitted to creating Blue Whale accounts to manipulate children into playing the game.

Russia’s Blue Whale challenge was soon followed by a similar phenomenon in the West. In July 2018, the YouTuber “Reignbot” published a video about a character called Momo, whom he claimed was sending disturbing images to children on WhatsApp and exhorting them to harm themselves or others. Once again, there was no concrete evidence that Momo was real, but this didn’t stop authorities and newspapers from treating it as such. A wave of moral panic spread across the internet, police warned parents not to let children use WhatsApp unattended, YouTube frantically began to take down or demonetize videos that even mentioned Momo, and, of course, some people created Momo accounts through which they sent children disturbing images and exhortations to murder and suicide.

The image used as the avatar of Momo accounts; it’s actually a sculpture by Japanese artist Keisuke Aiso

Momo and the Blue Whale Challenge, like Slender Man in Waukesha, acted like thoughtforms, materializations of real monsters from imagined ones. But there is another striking similarity between the administrators of the suicide games and the gangly monster in the business suit; they were faceless corruptors of children.

Curiously, this trope also happens to be by far the most common theme among viral creepypastas. It is epitomized in the creepypasta subgenre of sinister children’s entertainment, the largest and most prominent of all creepypasta subgenres. These stories typically involve a seemingly innocent children’s amusement having something devious and dangerous about it, usually leading to some combination of madness, brainwashing, and death.

This corrupted and corrupting entertainment often takes the form of a video game, like in Polybius (the first gaming creepypasta), Ben Drowned (the most viral), and Petscop (which innovatively tells its story through YouTube videos).

More often though, the sinister entertainment takes the form of a kids’ TV show. The most famous of the kids’ show creepypastas is Candle Cove, which is structured as a message board discussion about a nostalgic kids’ show that may not have been broadcasting at worldly wavelengths. It became so popular it was itself turned into a TV show. Other viral kids’ show stories are Where Bad Kids Go (brief) and 1999 (long), both of which evoke their chills by foregoing the supernatural and focusing on the very real horrors of child abuse.

If sinister children’s entertainment is the most popular subgenre of the creepypasta, and sinister kids’ TV shows is the most popular sub-subgenre, then the most popular sub-sub-subgenre is the lost episode. This typically involves a mysterious entry in a familiar TV series that contains disturbing content, usually involving suicide. Examples include Squidward’s Suicide (lost SpongeBob episode), Dead Bart (lost Simpson’s episode), and Suicidemouse.avi (lost Mickey Mouse episode).

The prevalence of kids’ show creepypastas, the moral panics of the suicide challenge hoaxes, and the virality of Slender Man show that something about the corruption of children by faceless entities strikes a cord with us as a society. This probably has much to do with our mammalian imperatives to be good parents, one of the most fundamental of human imperatives, and therefore one of the strongest.

Something about the corruption of children by faceless entities strikes a cord with us as a society.

Unfortunately, the sinister kids’ show creepypasta has something else in common with Slender Man and the suicide game hoaxes: it too acted like a thoughtform, erupting from the realm of fiction into reality.

From around 2014, bizarre videos began appearing on YouTube. The early ones tended to be live action, with people dressed as familiar kids’ show characters like Spiderman and Elsa from the movie Frozen. These characters would act in unsettling ways; sometimes they would take drugs and perform sexual acts, sometimes they would die while gorily giving birth, sometimes they would do nothing but babble incomprehensibly. Incomprehensible babble also filled the comments sections of such videos.

Soon, animated versions of these shows began to flood YouTube. Many of them had the air of sinister lost episodes, with normally innocent characters like Peppa Pig doing things like eating human flesh or burning down homes.

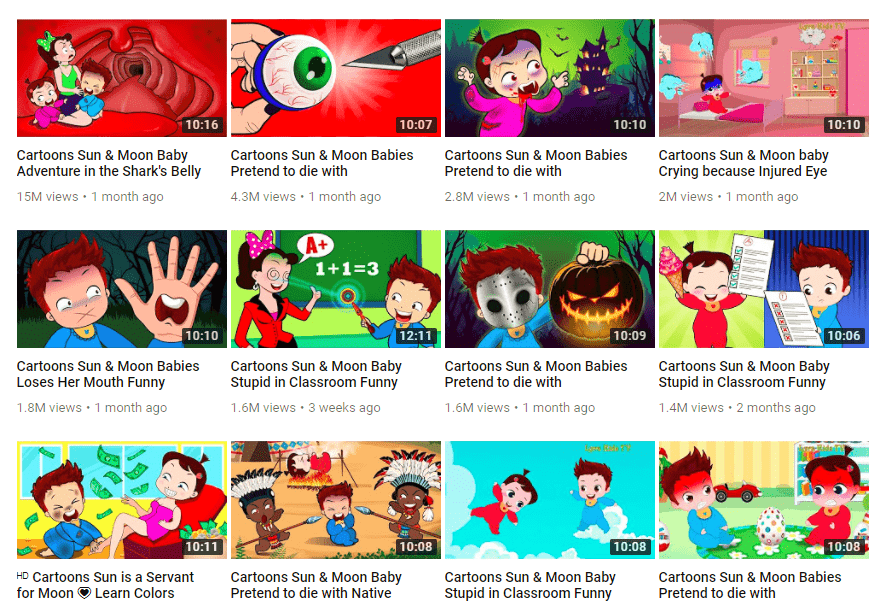

A typical selection of videos offered by an Elsagate account on YouTube

These videos were invariably tagged to appeal to children rather than adults, and they tended to get many millions of views. After parents began to complain about such videos disturbing their children, news media picked up on the phenomenon, leading to a global scandal dubbed “Elsagate.” YouTube and governments around the world have since gone to war against such videos, but with over 80 years of video footage uploaded to YouTube every day, it’s not possible to catch every perversion of kids’ entertainment before the harm is done.

But why exactly are so many of these eerie videos being turned from fiction into reality? And why did some people feel the need to create real versions of Momo and the Blue Whale Challenge? It may have something to do with the reason people create and share creepypastas. Namely, horror provides pleasure not only in the receiving but also in the giving. The amusement of watching someone freak out over something fictional. The comfort of escaping banality by role-playing monsters. The raw thrill of power that comes from spreading terror.

If the Waukesha stabbing shows that people can be turned into monsters by the desire to believe in them, then Elsagate and the suicide challenges show that people can be turned into monsters by the desire to convince others of them. Thoughtforms may not be real, but the most viral creepypastas, by virtue of their hold on our minds, come unnervingly close.

Thoughtforms may not be real, but the most viral creepypastas, by virtue of their hold on our minds, come unnervingly close.

However, despite the real-life horror stories, the tragedies, controversies, and moral panics that have besmirched the creepypasta, this format of digital folklore is likely here to stay. It exploits our ancient desire to scare and be scared, yet is modern enough to spread across the internet and to keep pace with evolving technology. As long as the web exists, creepypasta will exist in some form alongside it, as its shadow, its phantom, its dark mirror reflecting its deepest fears.

Creepypasta tells us that our deepest fears are haunted information, corruption of children, and faceless entities. But, in the wake of the suicide game challenges, the Slender Man stabbing, and Elsagate, perhaps what we should fear most is our capacity to make our nightmares real.