De-Fueling the Apocalypse

By James Workman

Staff Writer

30/1/2020

Picture Credit: US Forest Service

In 2019 Spain, California, and Australia experienced record-breaking conflagrations. To fully understand why, one must delve beyond the usual suspects – coal-burning power plants, gas-guzzling SUVs – to consider what quietly unfolds on abandoned rural lands.

Out there, nature rolls back centuries of careful stewardship with astonishing speed. Within weeks, weeds infest cultivated row crops. After months, scrub chokes manicured gardens. Over a few years, saplings spread roots under empty pastures, creating dense forest.

This metamorphosis may appear healthy progress. Manmade order rewilds back into native plants and animals, a rural playground where adults escape urban stress and kids explore dark woods. Yet nature cares not what we do or think. It’s indifferent. As the 19th century atheist and statesman Robert Green Ingersoll observed: “In nature there are neither rewards nor punishments; there are consequences.”

“In nature there are neither rewards nor punishments; there are consequences.”

Back when he wrote that, nine out of 10 humans still cultivated rural lands; in return, lands defined our culture. People hunted wildlife, gathered plants, tilled soil, grazed livestock, and cut down trees. Our species was more exposed and responsive to nature.

Today, the reverse is true. Across Southern Europe, Western America, and Eastern Australia, 90% of the population has urbanized. Rural life has emptied into Marseille and Melbourne, Sydney and San Francisco. These and other information-age cities are filled with industrial and service employees watching Netflix, tweeting emojis, ordering take-out, and emphatically disconnected from the vast and depopulated and no-longer-working landscapes that surround them. Beyond suburban developments or subsidized irrigated agribusiness are wildlands overgrown with dense thickets of trees, neglected or preserved in a cultural vacuum.

But not an ecological one. Day by day, for more than a century, these wildlands have been busy: desiccating during longer summers, withering under an increasingly hot sun, competing for less water and nutrients, and suffering from disease and malnourishment. The result is a sick tangle of forest scrubland waiting for dry lightning, or a match, to explode.

***

Fire requires three elements: oxygen, heat, and fuel. Our discussions about forests and wildfire tend to focus only on the first two.

Students early on learn the magic of photosynthesis, how forests inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen. Such a miraculous transformation – the opposite of human lungs – excites the imagination. Our efforts to capture emissions and cool the planet have included an initiative, a project, a campaign, and even a Republican draft Act in the US Congress to plant an additional trillion trees in the coming decade. The latest reforestation effort, launched at Davos, united Jane Goodall with Donald Trump. Billionaire Marc Benioff, CEO of cloud-based software company Salesforce, pledged financial support, saying: “Trees are a bi-partisan issue – everyone’s pro-trees.”

Trees cleanse the air. Carbon emissions trap heat. None of this is in dispute in the scientific community, and the emphasis on climate change may help reverse tropical deforestation and make fossil fuels prohibitively expensive. As temperatures rise and flames spread, it’s tempting to see escalating wildfires as payback for climate change denial, a simple narrative that feels almost religiously satisfying.

But there’s a catch. And it involves that third and ignored element of our fire triangle – fuel.

Global warming remains a threat multiplier for wildfires. But let’s imagine that decades ago benevolent and competent governments embraced the Kyoto Protocol and planted not one trillion but four trillion trees. Emissions tapered; temperatures subsided. Would Australia’s forests keep turning into a flaming hellscape?

The troubling answer, as any wildland firefighter will tell you, is yes.

***

In war, national heroes tend to be soldiers. Likewise, our century-old escalating struggle against burning forests – battles fought with blades, sieges, ground troops, tankers, tactical bombers, and parachuting behind enemy lines – makes heroes out of firefighters. Such was the romance that while I managed to avoid conscription into any army, 20 years ago I eagerly volunteered to join a Hotshot crew trained to “fight” wildland fires. It was as close to active military service as I’ll ever get. To “hold the line” and “outflank our foe,” we dug trenches with a combined pick and axe tool called a Pulaski, removed trees with chainsaws, watched each other’s backs, and followed orders from seasoned leaders using soot-stained, dog-eared copies of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War as a guide.

The author, with chainsaw, culling trees, July 1999

There were other parallels with warfare. Instead of officers, our civilian army honored the unspoken hierarchy of special forces. Us grunts looked up to sawyers, who admired structural and engine crews, who aspired to rappel down ropes from choppers (Helitack) or jump out of planes (Smokejumpers). And the truly elite, the Navy SEALs of the fire world were the Aussies. Our tinderbox forests of lodgepole pine or Douglas fir couldn’t hold a candle to their oily and resinous native eucalyptus trees that ignite and explode like jet fuel. Lately, trans-oceanic alliances have formed. In 2018, some 130 Australians deployed their very best to help contain California’s deadly flames; last month US crews headed Down Under to repay the debt.

Yet as with past wars on communism or terror, these same warriors have been among the first to realize the limits, or even futility, of billion-dollar campaigns waged against an abstract noun. What I discovered that summer is that, just as military victory is never complete, even the best crews never really “put out” wildfires for good.

What does? Nature, in all its indifference. Winds die down; rains fall; temperatures cool; vegetation thins out. Unfortunately, right now, each of these dynamics continue to trend in exactly the opposite direction.

Worse, another secret I learned from veteran fire crews across the Western US and Australia is that not only do our suppression campaigns fail to extinguish flames, our aggressive efforts to do so often make matters worse.

The reality is that dryland forests evolved to burn. In arid regions, forests need fire to build resilience for the same reason deer and antelope herds need predators to become swift and alert. Fire culls the young, weak, ill, and senescent; without fire, too many individual organisms overcrowd the landscape, overwhelming its carrying capacity, until the whole begins to starve, sicken, collapse.

Fire culls the young, weak, ill, and senescent; without fire, too many individual organisms overcrowd the landscape.

Indigenous people who coevolved with forests in Australia and North America long understood these linkages. They deployed fire as one of their oldest and most potent tools, burning deliberately on a rotating basis to spur new growth, attract game, and recycle nutrients. Tribes mimicked and adapted fire behavior over thousands of years; some still do. Ancestors passed down fire skills as a tool more vital to hunting than the plough was to farming. Their relatively cool, slow-moving, and periodic, controlled burns created a resilient forest “mosaic” with fewer trees of various sizes, stages, and ages. The mix of green grass and diverse forest attracted browsers and grazers as prey, while reducing the odds or severity of the high-intensity all-consuming fires that get fueled by dense uniform growth – the kind we see everywhere today.

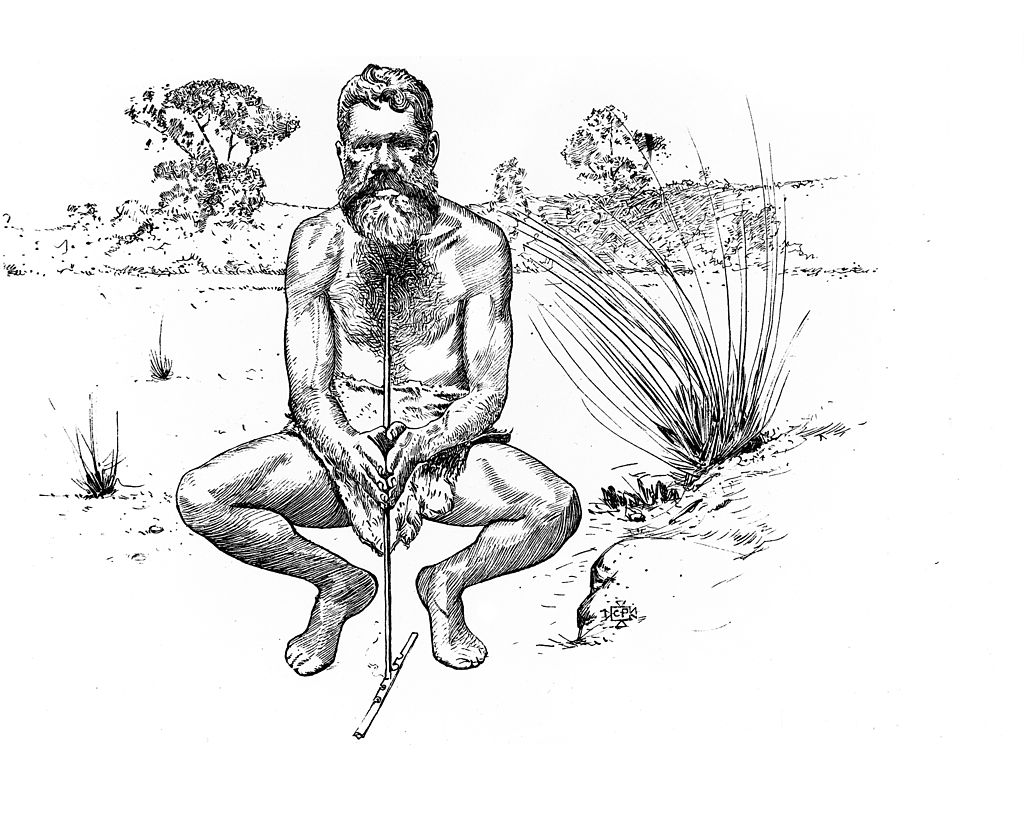

Australian aboriginal making fire

Settlers from rainy lands put an end to ancient practices. European ranchers and farmers and foresters loathed fire as an evil, and belittled indigenous knowledge as folk superstition. Australian officials ignored Aboriginal techniques, while in the Western US scientists sneered at “Paiute forestry.” Finally, 20th-century urbanization, combined with rural fire suppression, resulted in a vulnerable landscape choked with fire-prone trees. The reforestation trend, so welcome in damp regions, should be discouraged on arid, inflammable landscapes. Our tree-hugging culture must get over the notion that if ten trees of varying age per acre are good, then a hundred such trees on that same acre is ten times better.

Our tree-hugging culture must get over the notion that if ten trees of varying age per acre are good, then a hundred such trees on that same acre is ten times better.

Instead, it’s ten times worse. It means all hundred trees competing for fewer resources and more prone to disease, resulting in ecological fragility and collapse.

But if urban modernity has severed the centuries-old intricate human relationship with trees, how do we fix it? Some say we must adapt and scale up indigenous methods, and learn, again, how to fight fire with fire. That’s one option. Still, given our need to reduce carbon emissions, and to avoid tinderbox blowups on hotter days, prescribed fire can be too volatile, a drug that may harm the very people and places it was intended to treat and cure.

A better bet is to invest in a restorative forest culture, one that embraces “fire surrogates.” Mechanical thinning, with chainsaws or even feller-bunchers, can mimic the flame without the risk, lung-choking smoke, and greenhouse gas emissions. Such labor-intensive work could employ fire crews year-round to inoculate forests instead of being forced into last-minute interventions with emergency room heroics. While thinning at-risk, fire-prone forests is expensive, it remains a lot cheaper, and safer, than the horrific alternative we see in the news.

Even if we discount lives saved and property protected, thinning the forest will likely pay for itself. First, even small trees can be milled for lumber or ground into pulp. Also, harvested trees keep the carbon sequestered rather than letting it all literally go up in smoke. So, by avoiding carbon released in just one season of out-of-control bushfires, Australia could have saved the equivalent of a billion dollars’ worth of carbon credit. Third, reducing dryland forests by 40% translates into a 9-16% increase in yield for groundwater and runoffs. Some estimate that California could get two dollars’ worth of water for every dollar invested in forest thinning. Finally, measurable gains in biodiversity – and thus revenues from the multibillion-dollar hunting, fishing, and ecotourism industries – would also result from healthier forests.

At root, culling trees means reinvesting in rural people. It involves a redistribution of urban wealth out to working landscapes, rebuilding a culture of dominion, an old word for respect for, care of, and stewardship over natural resources. For centuries, dominion recognized that forests depend on humans as much as we depend on them. Our fates are intertwined. If we neglect or abandon our role, escalating conflagrations will continue to be one of the consequences.

And so, to save the forest, we need to revive the ancient practice of killing the trees.