FICTION | The Tunnel

By Ankur Razdan

Contributor

8/5/2020

It’s not so bad, as long as nobody goes outside. Mom sits with her laptop at the table; she’s working from home and looking for jobs while I do my homework. My grades weren’t very good before when school was open, but now that there isn’t any school, I feel pretty smart about it.

“There is school, mister,” says mom tapping her finger somewhere. “Homeschool.”

But it’s not the worst, because she got a big stack from Mrs Philips of all the packets I never finished, and now she hands me one or two every day to fill out while she drinks tea and types on her laptop, and they really aren’t as hard as for some reason I thought they were back then. And then once I’ve finished the packets and Margaret checks them, and if nobody else is using the TV, I can put my headset on and play Fortnite with all my friends. To be honest, I’m starting to get a little tired of Fortnite, but it’s where all my friends are everyday, and I haven’t seen any of them in about five weeks. Sometimes we just take potshots and talk. I don’t think I’ve done the floss dance in days. I tried to put all that into words for mom once, and she looked at me with her eyes kind of glassy as if I had just walked in the house for the first time ever and she had no idea who I was or why I was there, and then her eyes returned to normal, and she said: “Oh my days. I never thought I’d hear that out of you.”

And went back to typing.

Sometimes I even like doing the packets, and ask for another one (but mom didn’t give me that same glassy look the first time I did that, she just turned around and whipped it out). Doing an extra packet also means Margaret has to grade more. She checks them while she’s doing whatever else she does all day up in her room, and she says she doesn’t hate it, but I can tell she minds. But mom told her to and I don’t think they can fight about whatever they want to now.

Margaret? Mog? She’s crafty. I told her that once and she laughed, and then she said yes, she liked that. She’s crafty and she’ll pick something more important to start a fight with mom about. One time she stole mom’s Target card and bought a whole bunch of crap. When mom found out, she made Margaret return all of it herself, the jewelry, the purses, the make-up, the books, the headphones. Some of it was really random stuff, hiking gear, and school supplies, and a slow cooker, and a few watermelons. Who buys a slow cooker and watermelons with a stolen credit card? Margaret. But there was one item that the store wouldn’t take back. It was a garden decoration made of stone, from their outdoor section, no refunds. It looked like an alien reptile-creature squatting in a Buddha-pose. Mom called it an idol and she really hates it, but she put it on the windowsill in our living room so that Margaret will have to look at that thing every day.

Margaret isn’t usually so impossible, when she decides to spend some time with us. Sometimes she borrows the car just to go for a drive and mom says, don’t you think Will would like to go, too? And she actually doesn’t seem to mind that I come with, even if she does make me sit in the backseat, and we drive around town, where there are still too many cars going around, and sometimes we even talk. One ride we were out for over forty-five minutes and I explained to her the whole plot of Infinity Train and she listened and asked lots of questions. Once I even described a Rick & Morty episode for her, but without going into the specifics, because I’m not allowed to watch it. I have to watch it on my phone at night in bed. So she’s not all bad, either.

And Mom likes some cartoons, too. Sometimes she puts on a few episodes of Samurai Jack, and tells us about how way back when she was an assistant at the marketing company that made the ads for it, and how it was a big deal, and after that Margaret and I always say here comes the big deal when she turns it on, and she doesn’t say anything about it anymore, but every few days we’ll still watch a few episodes. Margaret doesn’t like cartoons. I’m not sure she likes TV at all anymore. She used to like documentaries about absolutely wretched people, but now except for going out for a drive or grading my papers, all she does is stay up in her room. When she acts mouthy, mom calls her Little Ms Joshua. Joshua is my dad’s name. My visits with him have been cancelled for now, as you can imagine, but I still FaceTime with him a few times a week. He always wants to know what’s happening. But nothing is happening, so there isn’t much to talk about. But if Margaret is watching less TV, that means it’s free real estate, as long as I do my homework packets.

Mom stocked up on a lot of good food before we started the quarantine, but the problem is she also bought a lot of canned food. I mean soup, but also canned tuna and canned fruit and beans and Vienna sausages and other weird things. I was looking through the pantry and found she accidentally bought a can of dog food too, and we don’t even have a dog. She makes us eat a little bit of the canned food every day. So I might have cereal for breakfast, and pizza or fajitas for dinner, but for lunch I have to have some salty chicken noodle soup or rice boiled in canned beef broth, or a tuna sandwich. And they only had rye bread at the store the last time mom went, so it’s even more disgusting. Mom says we can’t just save all the canned stuff for the end, we have to use it up the same as all the other food.

But in fact, right now it’s better than school. At first, when school was cancelled, I was really scared. I would never go outside and whenever someone so much as passed by the window, my arms would shake a little bit and I would hide my face. I asked mom all kinds of questions about the virus and looked them up online too when she didn’t know or when I thought her answers were wrong. She would hold me close and tell me why it’s okay to go outside. I thought about Margaret coughing and coughing and her asthma turning her lungs into a toothbrush or the teeth of a baleen whale, or mom wrapping herself up in bedsheets and getting black bumps growing out of her armpits like in the black plague video we watched in social studies. One time mom asked me what she could do to make me feel better, and I told her that everybody had to agree not to go out unless they needed to. To agree not to have contact with anybody outside the house. And not to bring it back inside the house with them. To take it seriously. She told me that that’s what we were doing already, but she promised she would make sure.

I told her that everybody had to agree not to go out unless they needed to. And not to bring it back inside the house with them.

The worst time was last week when we found out Scott was killed. He’s our cousin, but he’s a lot older than me. He was in prison, in Colorado, for touching a woman’s butt when she didn’t want him to. Mom said there was a prison riot because of the virus somehow and a lot of prisoners died. I tried looking it up online but I couldn’t find anything about it, but I also wasn’t sure what the name of the prison was that Scott used to live in. Mom was on the phone every single day with Aunt Mariska, Scott’s mom, and she always started crying. I cried a lot too when I found out, although I don’t know why, because I didn’t actually like Scott very much.

The second worst time was when Mog went crazy about her popsicles. That was about three weeks ago. She had been extra quiet lately. Up in her room most of the time, but with no music, which was unusual. But sometimes she would raise her voice. She must have been talking on the phone. Mom told me specifically not to ask her about it, while we were doing a jigsaw puzzle filled with the faces of musicians she likes. And when Margaret did deign to descend the grand staircase and grant us her company, she didn’t say anything. She would just kind of observe us. She would be in the opposite end of the room from you, curled up in the nook or lurking in the mudroom, and do that thing where people watch you without looking right at you. I didn’t like it.

And so one day mom and I were playing catch in the back yard and we came inside. And same as always Margaret was looking at us, but straight on this time. She went to the freezer without taking her eyes off us and opened it up and came out with a six-pack of popsicles in a freeze-it-yourself mold. I had snuck an ice cream sandwich out of the freezer just an hour or two before, when mom wasn’t looking. I hadn’t noticed the popsicles there. But more importantly, I wasn’t really in the mood for sweets.

“You guys look so sweaty,” Margaret said. She said it in a way that reminded me of Hannah or Peter from my class when they’re answering questions and they know they have the right answer and they’re acting really unbearably smug about it.

Mom did the honors of running the mold under some warm water for a second or two and broke us out a popsicle each. Their popsicles disappeared like they were under attack. Mog in particular was really sucking at it, slurping at it, and getting the melt all over her face. Mom kind of gave her a look. But she loves popsicles and ice cream, so she didn’t hold back either.

Mog in particular was really sucking at it, slurping at it, and getting the melt all over her face.

I, however, wasn’t about to touch the thing to my face. Its color was gross, yellowy green, like pee or frozen lentil soup. Did a friend of hers drop this off while mom and I were out back?

“Aren’t you going to eat your popsicle, Will?” asked mom.

I squirmed in place. The juice was melting down the stick. I grabbed a few napkins from the pile on the table and used them to block my hand from the melt.

“What’s this made of, anyways?” I asked Margaret.

“Frozen Mountain Dew.” Margaret stopped being obscene with her popsicle, which was half-gone, and wiped her face with the back of her hand. “C’mon, eat it, Willy. I made them just for you two.”

“Will, Margaret was really nice to make these for us,” mom said. She grabbed a napkin too, and I saw Margaret had a look of disgust on her face as she watched mom wasting her precious juice.

I stared at my popsicle. Even at the time, I didn’t believe it was Mountain Dew. It was like a weird jewel, the light went into it for miles and miles inside. And then when I looked close enough, I was able to see that it was actually glowing slightly. The glow wrinkled around itself, the way worms and maggots fold over on themselves.

It was like a weird jewel, the light went into it for miles and miles inside.

“Eat it, you little shit. I was only trying to be nice.”

“Margaret!” said mom.

“No!” I yelled, and plopped my popsicle back into the mold. Margaret came over to me and with one hand grabbed my face and with the other took my popsicle back out of the mold and tried to mush it into my mouth.

“Eat it! It’ll make you better!”

She would have got it into my mouth too, except her hands were so slippery that she couldn’t hold on to me. I ran over to mom. I hugged her tight and pressed my face into her shirt, wiping the juice off of me.

“Margaret!”

“You don’t deserve it!” Margaret screamed. I couldn’t see her but I could hear her, and I imagined her face twisted up like a rotten grape. I turned around in time to see her grab the popsicle mold and head down the hall.

Mom followed her and I listened to them argue. Apparently, Margaret wanted to go outside, but mom told her in no uncertain terms that it would be dark soon and she had to stay inside. Then I heard her pound the steps of the staircase with her heavy feet, and then the loud slam of her door.

“Your sister’s just emotional. I think she’s having boy trouble. Be nice to her when she comes down again,” mom said to me when she came back in the kitchen, which was clearly her last word on the matter.

I don’t know what Margaret did with the mold up in her room — we haven’t had popsicles since.

With all of the birds and the flowers coming out with all the colors, it was only a matter of time, and also inevitable, that I would start to get less scared and go outside more. I don’t even think twice about riding around on my bike or going on walks, or even driving with everybody different places outside the city, because I keep a social distance from people. But I normally don’t go by myself. Last week we all went for a walk. Most of the time it’s just mom and me who go, Margaret never wants to. Her eyes have a lot of dark blue under them like she’s wearing too much make-up again and mom says she’s too pale and Margaret says that she hates the sun. But this time when mom asked, Margaret surprised us both and said, yes, like she was hungry and mom was asking her if she wanted an extra flapjack. So we went out with the flower petals falling from the trees like snow on the cars and people walking their dogs crossing to the other side of the street from us, and mom occasionally ran into some grown-up she knows. But none of my friends actually live in our neighborhood, so I didn’t run into anybody I knew. There are some boys my age on my street, I see them walking with their parents, but how can I make friends with them under the circumstances? So I stay away from them the same as everybody else.

The funny thing was this time, mom pulled out Margaret’s old purple roller blades from the garage. She tried them on and she said they fit her perfectly, and when she asked Margaret if she minded Margaret looked like she was considering changing her mind about the walk and then she looked like she was about to throw up and then she looked hungry again, and she shrugged and didn’t say anything. So mom was gently gliding down the smooth asphalt with her hair lifting behind her head while I stayed on the sidewalk, and Margaret gave us a wide berth to our rear. Every once in a while, mom would circle back to me or Margaret to chat, skating in a zig-zag to stay as slow as us. She was doing that when a man came up the sidewalk walking his bicycle, and sitting on the bike from seat to handlebars was a huge rug. It was wrapped up so you couldn’t see the inside, but I imagined it was a big Persian rug. It was tied up with strips of see-through green plastic and it was really big, like a fat burrito. As soon as the man passed behind us far enough, mom said: “Where did he get that thing? It looks like he just bought it. You think he got it from one of those rug stores on Wisconsin?”

“I think he did,” said Margaret.

“How are they still open? To be honest, I wouldn’t call that essential services. Who needs to go shopping for a Persian rug right now, in this whole situation?”

“I know! Isn’t that ridiculous? What is wrong with people?” said Margaret in a high girly voice, and then the two of them started complaining and making fun of the rug guy together and they seemed to be having a lot of fun. When we got home they were smiling and making jokes like they liked each other.

And that was a good thing, because lately, I don’t know about Margaret. Blowing up over some popsicles, that’s just one small part of it. Before all this happened she had a lot of friends and used to go out every weekend. One day she was doing dishes and looking depressed and said: “You know, I never realized there were some things you could do without.”

And mom made fun of her, saying: “Like partying? Like using your fake ID?”

And Margaret made her mouth look like she had an underbite and didn’t say anything.

“That’s kind of adorable,” mom said to me, once Margaret had stomped upstairs, and she went back into her laptop.

But here’s the thing. I started to suspect that Margaret was going out anyways. That she was endangering us. Some nights I could hear a weird noise coming from outside my window — but it wasn’t weird at all, it was the end of the drain pipe that shakes sometimes when Margaret is fiddling with her own window. I didn’t believe it at first, I thought it was a squirrel on the roof, or something — who could be so stupid as to break our quarantine? Mog, that’s who. So one night, after I heard the sound again, I got out of bed and put my puffy jacket on over my t-shirt and underpants, and went around to the side of the house where our windows are. I tried her window mechanism and it was open. Open! I looked inside the dark window and then looked away again. I thought, what if I’m wrong?

I started to suspect that Margaret was going out anyways. That she was endangering us.

The next morning I watched her over my cereal. Mom was eating cereal too and she was already on her laptop with her reading glasses on, but Margaret made herself some bacon. She looked tired, exactly as tired as you would expect if you’d been doing shots with Chrissy and taking drugs around a bonfire all night. She bit down on the bacon and rolled her head to tear away the bites, and then looked at me and said: “You good?”

And I said: “Yeah, Mog, I was just waiting to see if you’re going to drip saliva all over the table.”

And she finished her bacon more normally and looked away from me and put her hand to her temple. But I was still watching her. Here she was, sitting at our table with us, putting our lives at risk, just so her normally scheduled programming wouldn’t be interrupted, while I was here everyday talking to my buddies on my headset and mom was sitting at the kitchen table all day sighing and doodling little figurines in her notebook. But we can’t have Margaret give up anything important to her. And who knows who her friends have been in contact with. She was going to bring it in and get us all sick, and a quarantine with secret hook-ups is not a quarantine at all. I watched her without disguising my hatred and she didn’t even notice when she said: “By the way, here’s your packet from yesterday,” and kind of threw it at me. From then on I never came within six feet of her. I starting leaving things out for her on the island instead of handing them to her, and I always washed my hands after touching something she touched.

She was going to bring it in and get us all sick, and a quarantine with secret hook-ups is not a quarantine at all.

A few nights later, I heard the sound again. I was not asleep, I was sitting at my desk. I was dressed. I looked out the window, I could see a dark shape, rounded and splintery, moving past the trash cans. That bitch.

I walked down the hall and knocked on her bedroom door. There wasn’t any answer. I knocked louder, but not loud enough to wake up mom. Nothing. I opened the door slowly. The lights were off, but I could see there was nobody in bed. I glanced over my shoulder at the hall bathroom. No light under the crack. I closed the door behind me and turned on the lights. I was a bit surprised. Usually her room is a sty, but now everything was very clean and ordered. No dirty laundry on the floor. I didn’t move for a few seconds, maybe almost half a minute. I didn’t have time for distractions, but it made me feel more like I wasn’t doing anything wrong, to go slowly. But I was right, because she wasn’t here, she was out getting the virus somewhere and she was going to bring it back. So I went to the spot behind her bed where I knew she kept her journal. I swear to God I have not read it in two years. It was a different one than last time, green instead of dark purple, and when I put my hand on the cover I thought about how long she’d be gone for. I never heard the sound of the drainpipe a second time in the night. I was always asleep.

I opened the journal and began to read. It was too bright around me — I turned on the frog lamp on the nightstand and turned off the fan light. I started to read again. It was even better than last time. Actually, for a while I forgot about this whole situation. She wrote about the girls she hates at school and she wrote about how sometimes she had a fantasy that someone stuck a vibrator up her butt and left it there while they had sex with her, about how only creeps asked her out, about taking moody walks out in the woods where she wanted to kill herself. Hilarious. She wrote about a guy she was in love with, about how his eyebrows were crisp like someone had drawn them with charcoal crayons and his cheekbones set her on fire and the fuzzy hair on his arms made his skin swim in light. But he never talked to her, and that made her feel like she was a creep. I stopped reading for a second and looked at my face in the mirror, and wondered if any girls I knew would have anything to say about my eyebrows. I didn’t see how they could and I went back to reading. She barely mentioned mom or me. It was a lot of fun to go through it, way better than Fortnite. I took some pictures of the best pages — I would have to read them to Jessie and Ashwin when we saw each other again.

But I was having enough fun. I skipped ahead to middle of the journal, the newest entries. There was nothing about sneaking out at night. Actually, she seemed to be writing less and less. And more and more of what she did write didn’t make any sense. They were just strings of letters, like this: jogurosuusengsapac,eriunodaobapeonvariunengiudaobicutjen.Iuximtekiowtwjumwumbhosxengjoximberv-picoobiforv.joxart-roiuuwxenggev-tsjen

I looked at these letters and tried to read them, but it made my brain hurt. Past a certain point, that was all there was. Her handwriting was worse, too. At first I thought she was crazy, but then I thought it must be code. I could break the code and see what she was writing about. I took a picture of one of the pages with code, put the journal back in its spot, and shut off the lamp.

There was a quiet knock on the door. I stood still.

The knock came again.

“Margaret?”

I sighed and opened the door. My mother looked surprised and stepped back. “Oh, I’m sorry, I thought — what are you doing?”

I remained tactfully silent.

She was about to brush past me into the room, I could tell, but she stopped herself. “Is Margaret in there?”

I shook my head. “Margaret went out for the night.”

Mom sighed.

“Margaret goes out most nights.”

Mom nodded. “I thought I’d caught her coming back.”

I put my hands on my hips and walked up right in front of her and looked up at her with my head pulled back. “Mom, she’s breaking the quarantine.”

“I know.”

“You know?! Where’s she going? She’s putting us all in danger! Why don’t you stop her?”

Mom looked down at me. “Go to your room. I mean, go to sleep.”

I started to walk down the hall but then I also stopped myself. “She’s going to get us infected, mom. You promised you’d make us all follow the rules. So we’d be safe. You have to do something.”

She sighed again and said: “Eventually.”

“But-”

“Here’s the thing, I don’t have…a, a, a magic sword I can chop your sister up with,” she said. She was irritated. “Go to bed.”

I went to my room but I didn’t go to bed at all. I pulled out the homework packet Margaret gave me at breakfast. I confess I had not perused it yet. I didn’t have a chance to yet. It was mostly normal. Lots of exes. She used to be really funny with her frowny faces, ugly and crying and lumpy. But not anymore. My finger followed her little notes but I wasn’t really reading them. My finger stopped. There, on the side of the third page, right next to where my answer about the Three-Fifths Compromise was splooged in red: nuvritarborik.niegmur

I dropped the packet on the floor and kicked it under my bed.

I stayed in my room most of the next day. I went to get food once mom and Margaret were done eating. After all, if Margaret had the virus, then mom would be just as infected by now.

If Margaret had the virus, then mom would be just as infected by now.

I never got around to cracking the code. I looked at a few articles about codes and code-breaking on Wikipedia but then I decided I wanted to watch some videos about custom Lego sets on YouTube, so I figured I would just follow her.

After saying goodnight to mom and listening out for her snores, which are very quiet and kind of adorable, I got dressed in my jacket and beanie and tennis shoes and sat in the dark on our front stoop, under the eaves. I turned off the front porch light and I imagine I was pretty much invisible in the darkness. Before too long I saw Margaret. She was walking down the street. She wasn’t dressed very warmly and the skin on the back of her neck was shiny under the moonlight. She seemed disturbed — I mean more disturbed than normal — she looked like she was kind of talking to herself very quietly. She pinched the skin on the front of her neck sometimes and held it there for a few seconds. I got up and started to follow her at a respectful distance. I figured she would walk out a ways, down to the end of the street, and get picked up by a car, and maybe I could recognize who it was, so mom could call their parents, or if it was a guy I didn’t recognize, mom could wallop her.

But she kept on walking. When we got out so far that I couldn’t see the house anymore, I stopped for a second. I looked at the puddles around the gutter and the bugs flying under the streetlamps and thought about how you don’t know what’s in the puddle, and how you wouldn’t know there were bugs if the streetlamp wasn’t there…But then I was about to lose her, and I stopped thinking and started following her again. Down the streets, into the forest, over the creek, slipping on the mud. I tried to keep up with my available means of stealth as best I could, and honestly there were some times when I made so much noise following her, got so close, that I thought she had to know I was there behind her. But she didn’t stop or turn around or anything.

We walked thru’ the cold and the wet and she breathed fast and I thought about her asthma. I wished I’d put my boots on instead of my tennis shoes. We went through the part of the woods past the DETOUR CLOSED sign, which isn’t such a big deal – there’s nothing dangerous about it. But then we went off the path, and she started to half-slide down one of the ridges. She scared some deer away and I had to apologize to them as I passed. She sunk down the ridge with mud on her knees and she pulled me after like I was on a string.

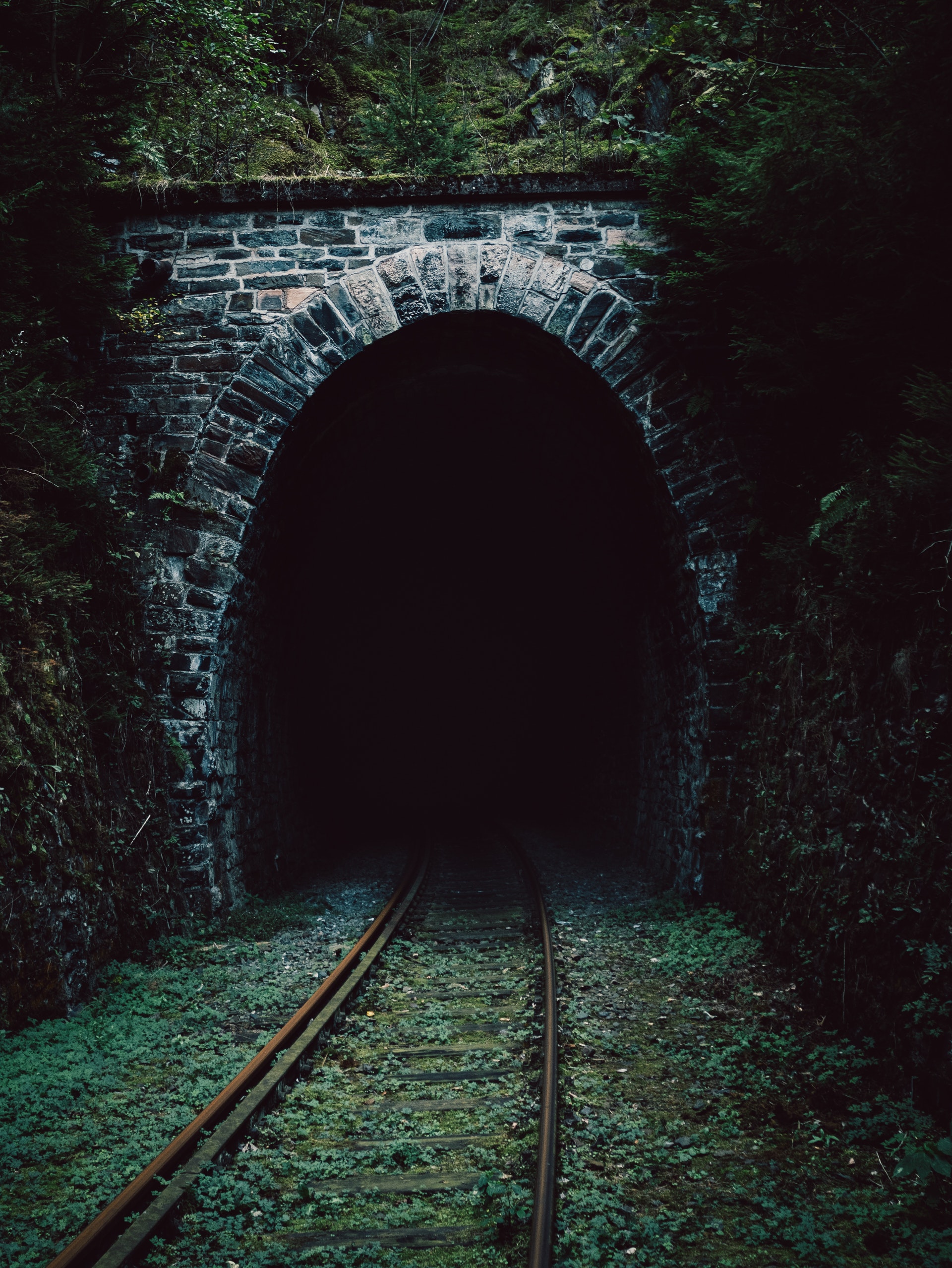

We got to flat ground again and then I saw there was a tunnel. She was walking towards it in a weird way, I hadn’t seen her like that since junior prom, kind of standing straight up and her head held high. She stopped picking at her neck and stopped muttering to herself and pulled out a pin from her hair and it came falling down. I guess the tunnel had to’ve been under the closed-down metro line. I had never seen it before. There was a glow or something coming from inside, sickly and green.

There was a glow or something coming from inside the tunnel, sickly and green.

Margaret went inside the tunnel and I was sure she was waiting just inside to grab me as soon as I went inside, so instead I crept around to the edge and looked around the corner.

The tunnel was so long that I couldn’t see the end of it. It was still glowing sick and green, but very strongly now, from these growths all inside of it — on the floor and the walls and the ceiling, hanging down like glowing worms or fungus. I spotted Margaret standing in the middle of the tunnel. She walked up to a stalactite of the glowing stuff, and her hair began to stand up. I don’t mean the hair on the back of her neck, which I couldn’t see, I mean the hair on her head. Then it got hard to concentrate because I was hearing booms of thunder from far off. But I knew there wasn’t any storm behind me, the booms were coming from a direction that wasn’t a direction I knew about before. I could feel them swimming up the tunnels towards me. The glow of the growthy growing thing was even stronger now and I noticed that Margaret’s eyes and mouth were glowing with the same gross light. She leaned her head back and put her mouth over the end of a stalactite and her whole body began to glow and I could see her skull through her skin, and where her lips ended and the stalactite began was not so clear to me. I was sweating a lot under my jacket and couldn’t breathe very well. Margaret’s face was floating on the big glowing thing and her limbs were sticking out somewhere else and it was getting harder to see anything, except for her eyes were so wide open and she was so so so happy.

Follow the author on Twitter @mukkuthani

Related posts:

Modi and His Supporters Face a COVID Reckoning

Tablighi Superspreaders in Pakistan

The Culture Factor in COVID-19

The Moral Foundations of Anti-Lockdown Anger

Are Anti-Lockdown Protests Legal?

Allegory in the Time of Coronavirus

Your Odds of Dying From COVID-19 Depend on How Polluted Your Air Is

Japanese Culture Isn’t Designed to Handle a Pandemic

The Coronavirus and the Crisis of Responsibility

To See How Coronavirus Outbreak might Play Out, Look at This Virtual Plague

FAKE NEWS | Nothing to Worry About, Says Wuhan Official From Inside Biohazard Suit