Free to Be

By Erin McIntosh

Staff Writer

25/3/2021

Outwardly, the gay community celebrates “being yourself,” embracing what makes you unique, and “letting your freak flag fly.” In actuality, the community itself can be incredibly stringent. Emphasis is placed on finding the perfect label, fitting the profile for it, and staying put. Then you’ll know which sub-group or category you fit into, and those are the people you’re allowed to be in a community with. It’s ironic, in a group presenting as the most accepting and open, how restrictive things can be. For a culture that purports to be the ultimate haven for freedom of expression, I never could find the right corner to squeeze into.

The more lauded we are for our individuality, the more easily we’re supposed to find our “tribe.” Tribalism is tied to survival, and outside of physical location, it’s what creates communities in the first place. We gravitate towards those we perceive as being most like us, whether in appearance, creed, or otherwise. I used to think part of being queer meant definitions were null and void, and that under this umbrella I no longer needed to conform to anything else, but the gay community doesn’t work all that differently from the tribe-mentality cultivated in any other kind of group.

Labels for gay men read more like a zoo exhibition than a category of people: bears, otters, cubs, pups, wolves, silver foxes, and so on. You also have twinks, jocks, daddies, and a myriad of other labels and types that are as excessive as they are specific. For women, you can be any one (or combination) of the following: butch, stud, tomboy, femme, lipstick lesbian, chapstick lesbian, soft butch, stone butch, stemme, androgynous, blue jean femme, boi, power dyke, and more. That’s not even touching on gender identification, such as nonbinary, genderfluid, genderqueer, or transgender.

When it comes to relationships, the gay community is also rife with heteronormativity. Stereotypically “masculine” or “feminine” roles play out in many relationship dynamics. Depending on what “type” you are, you’re expected to have a partner that correlates — for example, if you’re a butch, you should be with a femme; if you’re a stemme, you should be with a soft butch, and so on. There are exceptions, of course, but deviations still cause a fair amount of head-scratching. As a pairing, my girlfriend and I caused confusion in gay circles, as neither of us were overtly “feminine” (whatever society has decided that means), and yet neither of us were bowtie-wearing butches, either. We’ve been viewed — and spoken to — by other gay people like we didn’t belong together, simply because others couldn’t make sense of us. We didn’t play by the rules of a predetermined binary.

Mostly, identification in the gay community has to do with aesthetic, no matter how much we say it’s about how we feel. It comes down to how you look and how you dress, including body type, which hardly seems fair — Kitschmix noted that a “tomboy lesbian” is kept from being a full-out “stud” by “her long hair and feminine body type.” In many accounts of queer discovery, physical presentation is key, like this one where it wasn’t until the author dyed her hair and got piercings that she felt able, in her words, to “experiment with queer fashion and be unapologetically myself.” In the comments, one response lamented: “Here’s yet another article equating queerness with how one presents.” Working an outdoor lesbian party on a blisteringly hot day, my boss at the time offered to lend me a pair of board shorts to replace my thick black jeans, suggesting they’d fit not only my body but my type: “They’re cute,” she said, “you know, for dykes. Like us.” It was jarring, as never in my life would I categorize myself alongside her, not because of style differences so much as what I saw as fundamental conflicts in personality and values. But she simply meant a certain kind of lesbian style: a tomboyish, Chuck Taylor-wearing kind; not exactly butch, but definitely not femme.

Aesthetic changes in a gay person are equated with transformation, but this quick-fix promise masked as empowerment is as superficial as any diet pill. Instead of cultivating confidence, self-respect, intelligence, or curiosity, a gym membership or slight wardrobe adjustment are all that’s needed, and voila, you’ll immediately qualify as a new kind of gay, with acceptance among a similarly-groomed tribe as the prize. This trend of wand-waving makeovers provides short-term catharsis, but ultimately it’s an empty vacuum where changing your closet or getting a haircut is suddenly supposed to make the pain of an unaccepting family or society dissipate. (Here’s looking at you, Queer Eye.)

There are suggestions that gay-identifying people seek more external validation than the average heterosexual because they didn’t receive it growing up. But when identity becomes solely presentational, all about how one wishes to be perceived rather than individualized self-expression, it starts to feel performative. One lesbian told me, matter-of-factly, that: “I was one kind of lesbian for a while, but then I became a different kind when I stopped wearing makeup, and then again last year when I cut my hair short. Recently, I stopped wearing skinny jeans, so apparently now I’m in a whole new category.”

This fairly new obsession with micro-labels could have something to do with the reach of “peak individualism,” often cited in regards to Millennials and Gen Z. In these generations, higher emphasis is placed on individuality, self-discovery, self-interest, and “finding yourself.” But the desire for uniqueness, when it supersedes all else, becomes tinged with narcissism, or what’s been termed “special snowflake syndrome.” It’s understandable: defining yourself as “a power-bottom genderfluid pansexual stemme” is a lot more exciting than being just, well, human. It’s possible there’s also a stronger connection now between identity, self-expression, and one’s personal “brand” by way of the bloated importance we’ve come to place on our online personas. The more unique and special we appear online, the higher our chances of fame, popularity, or endorsement deals. Social media has turned our obsession with being noticed into the Hunger Games of identity politics. When marketing the self via social media platforms becomes not only a trend but a lifestyle or even a viable career, identification is everything.

When marketing the self via social media platforms becomes not only a trend but a lifestyle or even a viable career, identification is everything.

“If you base your self-concept on what you think others think of you, then you will always be vulnerable,” wrote Elizabeth R. Thornton in an article in Psychology Today. The need for external validation is “rooted in an overall model of insecurity or ‘I am not good enough.’” When how you present — and thus, how you’re perceived — rules your sense of self, you’re going to risk authenticity for social acceptance. How others respond to you will then determine how you feel about yourself. Psychologists C. H. Cooley and Han-Joachim Schubert call this phenomenon the Looking-Glass-Self: “I am not what I think I am and I am not what you think I am; I am what I think that you think I am.” True individuality, though, doesn’t always lead to manufactured acceptance into a given group or community of choice. That can be terrifying, and it’s far safer (not to mention more comfortable) ascribing to a status quo just for the sake of fitting in.

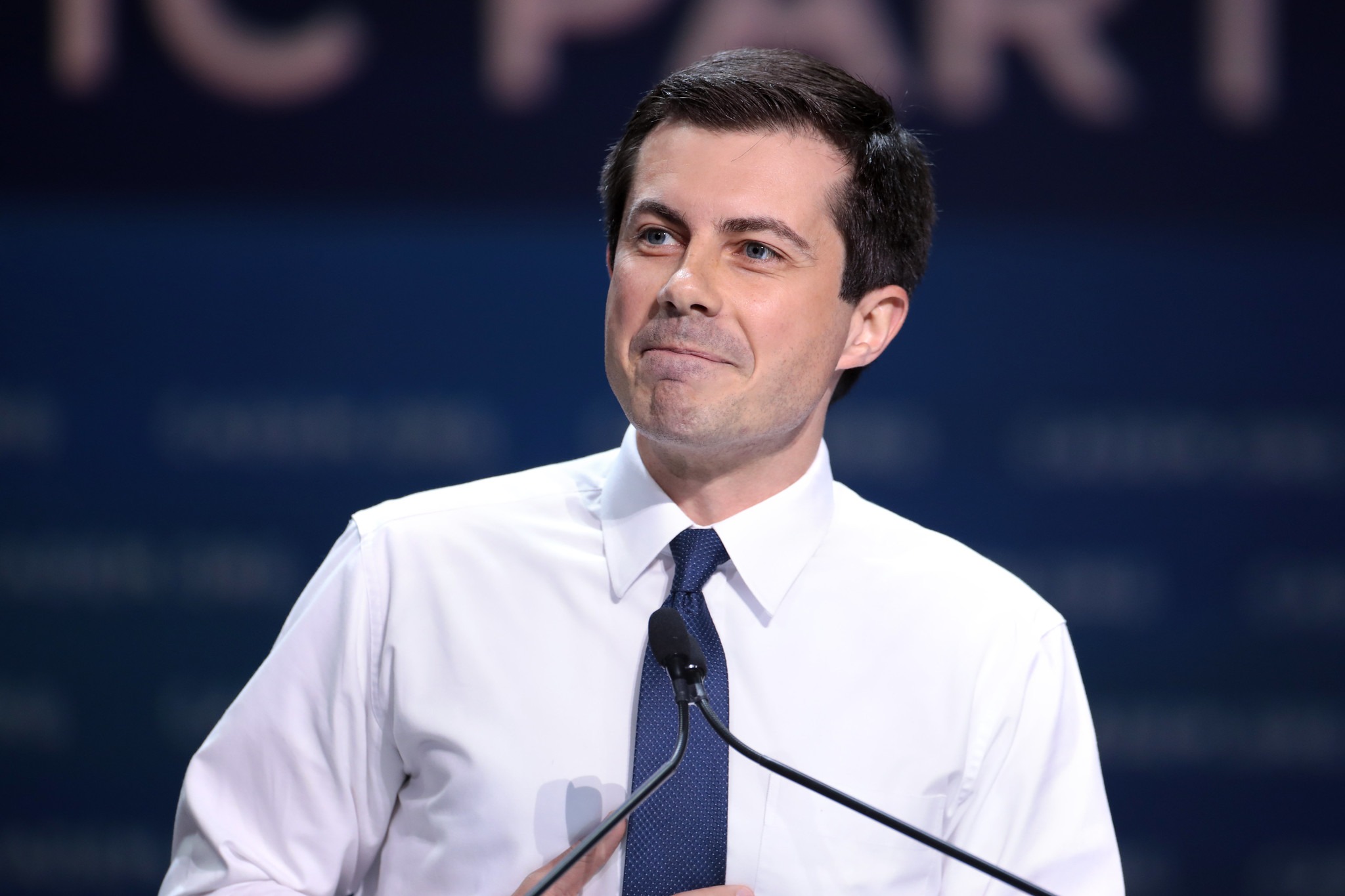

At best, an individual can use their labels as a way to feel a sense of belonging, but at worst, pressure to conform by way of presentation can be downright ostracizing. Only last year, when Pete Buttigieg, a gay politician, made a bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, he was criticized in the news — including by other gay people — for not being “gay enough.” Accusations included that he “appears straight,” “acts too straight to have any gay cred,” and that his “ties to straight culture” are “sturdy.” In the 2010 documentary The Adonis Factor, a film exploring issues of body image in the male gay community, many of the interview subjects admitted that their community is largely “a culture based on sexuality,” and when that’s the case, looks are what matter most. “A lot of people think the more attractive they are, the more they belong in the community,” said one participant, citing a competitive element to belonging that can easily become engrossing. Those who devoted their lives to the gym and partying felt they were living the good life, but those who didn’t look a certain way felt dismissed by a community that preaches tolerance and embracing all of who you are. These outsiders, feeling “not good enough,” often experienced a low sense of self-worth and belonging.

Pete Buttigieg: not “gay enough” for some people (Picture Credit: Gage Skidmore)

Back when I was still figuring out my own sexuality, a friend jumped down my throat when I tried the simple “lesbian” label on for size. She, a newly-minted lesbian herself, told me I couldn’t claim that word, that I shouldn’t use it unless I was absolutely sure of it, and I left the conversation feeling more ashamed and confused than I already was, which was saying something, considering I was in the midst of coming out (literally and figuratively) of a religiously repressive upbringing, making the question of sexuality as a whole ambiguous at best. The irony, of course, was this same friend later renounced her lesbian identity and came out all over again as bi, and then as a myriad of other things, most of which I lost track of over the years. She shifted her identity to whatever suited her personal whims and fancy, always holding it as canon until she felt like changing it, while at the same time becoming possessive and prickly about anyone else’s experimentation in their own search for definition. I wish I could say her behavior was an anomaly, but in the gay community, a demand for fixed identity in others is often married with the hypocritical whiplash unveiling of ever-new personas.

She shifted her identity to whatever suited her personal whims and fancy, while at the same time becoming possessive and prickly about anyone else’s experimentation.

Feeling seen and heard are basic psychological needs. On top of that, personal identification and experience are massively nuanced and varied. As someone who struggled to understand her own place in the gay “community,” I can’t say my life got better the more I sought to identify myself. The über-specificity felt like a court sentence, like once it was settled on, I wasn’t allowed to change my mind. I met a woman who identified as gay, and for many years only had relationships with women, until one day she met and fell in love with a man, whom she married. She spoke about how the ostracization and discrimination she experienced from the gay community was in some ways worse and more painful than what she experienced when she initially came out to the conservative, religious people in her life. Her community viewed her identity change as a betrayal, and they, in response, turned their backs on her.

In my mid-20s, I began enjoying the swagger of what I considered to be more masculine-presenting way of being in the world, and I liked the way people responded to me differently the more I leaned into this. Embracing it, though, put me in another lane in terms of how I was perceived in the gay community, and I spiraled for a second about my “identity” before having an epiphany. I realized much of what I was doing had little to do with what was most natural or organic for me, and everything to do with other peoples’ perceptions. If I forced myself to stop thinking about how anyone else saw me, or worrying how they might respond differently to me based on my “look,” where would that leave me? What I discovered is that it’s pretty fluid. One day I’m happy in a blazer and tie, and the next I’ve got on a tight tank-top and skinny jeans. Not only is that okay, it really doesn’t matter. There are bigger things I want to spend my time and energy thinking about other than how I’m being received.

Interestingly, an increasing number of young celebrities are embracing sexual fluidity and ambiguity, repudiating any pressure to label it, like when Janelle Monae and Tessa Thompson declined to define their relationship, or when Kristen Stewart refused the inauthenticity of an official “coming out” moment. “If you feel like you really want to define yourself,” said Stewart, “and you have the ability to articulate those parameters and that in itself defines you, then do it. But…I live in the fucking ambiguity of this life.” Taking it a step further, Miley Cyrus not only refuses to ascribe to any label pertaining to sexuality, but also with gender: “I don’t relate to being boy or girl,” she said, “and I don’t have to have my partner relate to boy or girl.” Some might critique this lack of definition as wishy-washy or cowardly, but it gives me hope. Saying one part of me is the sole or most important defining aspect of my personhood is ridiculous. Our lives constantly change, and so do we. An opportunity to evolve ought to be welcome and celebrated, but when one’s entire life (social group, relationships, career, wardrobe) is based on one specific identity, rigidity might ensue in order to ensure that nothing threatens that image.

The constant squabbling around labels seems especially superficial in light of what goes on for queer individuals in other parts of the world. In many countries, including parts of Europe and the US (conversion therapy is still legal in 30 of 50 American states), being gay is either barely acceptable or punishable by death. Being gay in these places is a life-or-death fight for survival and basic human rights. To this day, in the UK, Austria, and the Netherlands, as well as in Canada, immigration officers deny asylum to gay refugees seeking reprieve from persecution for the same superficial concepts of aesthetic I’ve described. Not having a significant other or visiting gay clubs was grounds for questioning the legitimacy of a person’s gay identity, with a cruel dismissal of context for the communities where they were coming from. Some candidates weren’t effeminate enough, some were too effeminate and thus accused of faking it. Clothing choice or the way a person walked made them suspect. In one case, a lesbian woman with actual videoed evidence of her sexual orientation was still accused of “performing sexuality” in order to sneak her way into the UK. The most banal dismissals were founded on an unfamiliarity with various gay television shows or movies. If that’s the case, never watching The L Word or Orange is the New Black would be enough to deny me, for one, access to safe asylum in any of these supposedly progressive countries.

If I’d discovered my local gay community earlier, as a newly-out gayby (there’s another label for you), it might have really rocked my world, in a positive and exciting way. But the stronger my own identity established itself, the more isolated I felt when encountering my supposed community. I didn’t want to be friends with someone just because we shared an attraction to half the population, or because their fashion interests fell under the same subcategory of a category as my own. I wanted to cultivate relationships based on similar interests, beliefs, or simply because we enjoyed one another’s company and were able to have stimulating conversations. I’m sure someone out there reading this will tell me I have “internalized homophobia” (a favorite phrase to malign anyone critical of LGBTQ+ orthodoxy who isn’t straight), but this isn’t self-hate. If anything, it’s self-preservation. That sounds dramatic, but walking away from the stringent expectations of the gay community only deepened my own self-love. When I stopped trying to form an identity based on who I slept with, how I dressed, the length of my hair, or whether or not I shaved my underarm hair, true individuality was allowed to bloom. In not actively ascribing to preconceived tropes, I’m able to thrive in a daily fluctuation of introversion and extroversion, bookishness and reality television, band tees and blouses. I feel free to flow and change precisely because I don’t ascribe to any one label or aesthetic. When acceptance from others no longer depends on fashion trends or who I choose as a partner, the pressure to perform dies. In not trying so hard to belong, I’m able to relax into myself and find self-expression in more organic avenues.

Back when I last attended and worked gay Pride events, every now and then, I would see someone who was a little different. Not because they had green hair or wore platform shoes — those were pretty normal sightings — but because they wore a simple t-shirt. On it, words like “gay” and “female” were crossed out. At the bottom, not crossed-out, was the word “human.” I always wanted to hug them.