Frozen Ambitions

By Julien Oeuillet

Staff Writer

24/2/2022

Antarctica is a place like no other. It is a rare case of a genuine terra nullius: it never had a native human population, and was never colonized. It only really began to be explored in the 19th century, and since then its permanent population has never exceeded a couple thousand people. Some nations claim part of it, but they don’t do much about it, and any scientific bases they build there may not even be located in the territory they claim. It is remote and inhospitable, and is regulated by an international treaty rather than national laws, its status as a no-man’s land maintained by a treaty signed by the world’s great powers. Now, though, that status might be under threat.

The Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959 and entered into force in 1961. People familiar with the treaty often say it “froze” territorial claims: it doesn’t extinguish various countries’ existing claims in Antarctica, but prevents claimants from conducting military activities on the continent and bars future claims. “The treaty has been into force for 60 years and it had its up and downs but is very successful,” said Donald Rothwell, Professor of Law at Australian National University. The Antarctic Treaty is a Cold War relic that aimed to prevent the Soviet-American rivalry from spreading to the continent. Neither the United States nor Russia claim any Antarctic territory, though they both maintain scientific bases there, as do many other countries, including China, Japan, Spain, and Ukraine – none of which have any territorial claims on the continent.

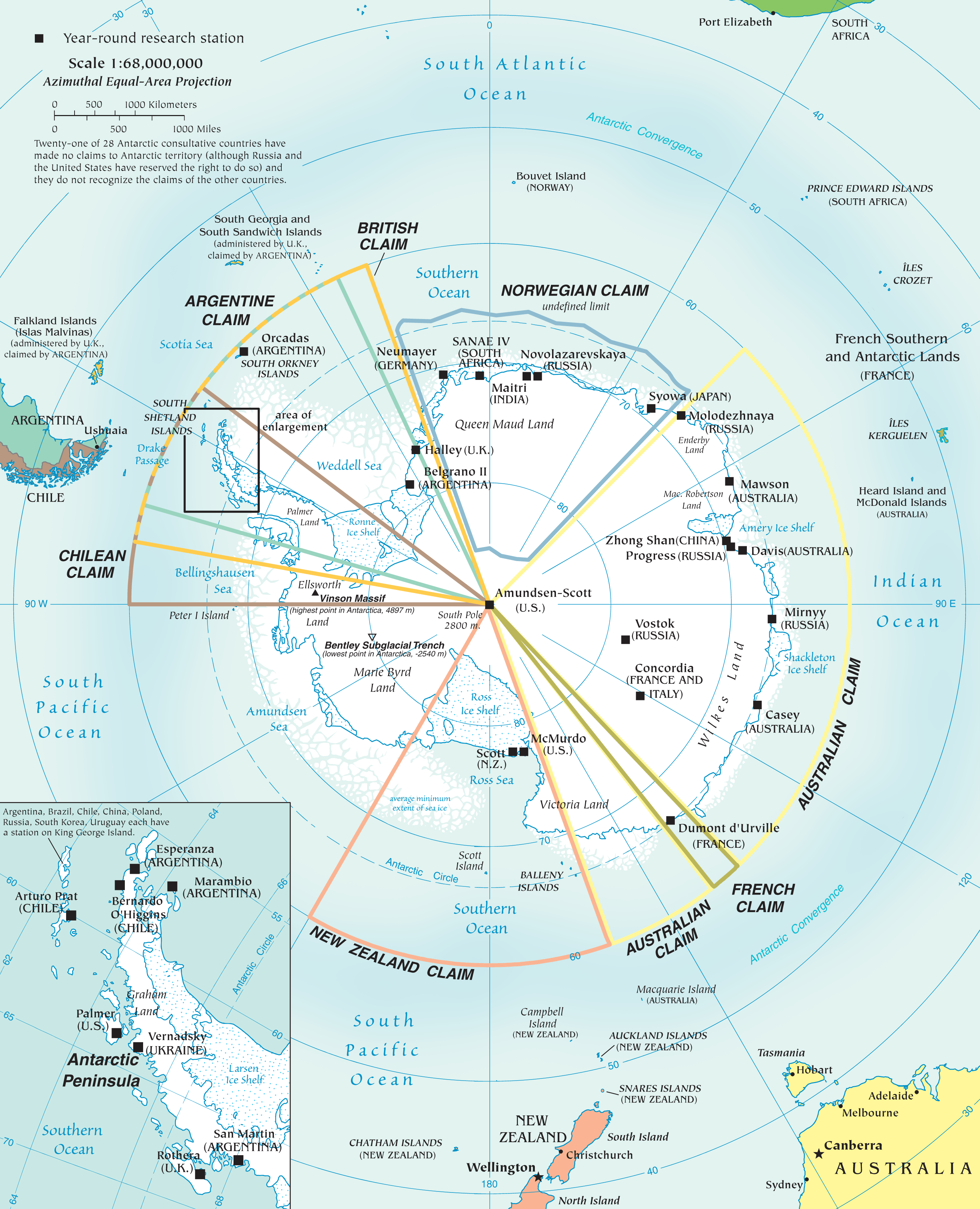

Currently, seven countries claim territory in Antarctica. Australia has the biggest claim (a whopping 42% of the total Antarctic surface), which it inherited from Britain. New Zealand also inherited claims from the UK. The remaining British claim is linked to its claims on the Falkland and South Georgia Islands. Both Chile and Argentina claim parts of the Antarctic territory in the same area, and their claims overlap with Britain’s claim and each other’s. France makes the smallest claim, based on its early exploration of an area that cuts the Australian claim into two parts, but the two countries respect each other’s claims, and they don’t overlap. The last claim, made by Norway, is historically linked to the whaling industry, and is located within the same longitudes as the Norwegian territory but on the other side of the world. One former claim, by the Third Reich, was withdrawn after the Second World War: its only legacy is a range of metallic poles bearing swastikas that were thrown down from airplanes, and an abundance of science-fiction and conspiracy theory books about frozen Nazis building secret weapons in a secret Antarctic base.

Antarctica (Picture Credit: The World Factbook)

Rather than the Antarctic Treaty alone, it is more appropriate to talk about the Antarctic Treaty System, a term used to encompass not only the original treaty but the treaties that were added to it (mostly related to ecology) and the institutions that emanated from them. The Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, based in Buenos Aires, has been tasked since its creation in 2004 with facilitating the exchange of information between the signatories. But the most important organ is the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting, an annual gathering of representatives from all signatories. This is where an important distinction must be made between the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties (ATCP), which are the nations with voting rights at the meeting, and the other signatories, who despite being present at meetings, do not. To become an ATCP, a country has to demonstrate a scientific interest in Antarctica, like having a scientific station or conducting a scientific expedition there – so if you sign the treaty but do nothing, you won’t be allowed to shape the future of the Antarctic Treaty System.

US representative Herman Phleger signing the Antarctic Treaty in December 1959. Phleger sent this photograph to Laurence McKinley Gould, a scientist and Antarctic explorer whose publications and lecture tours on his polar experiences helped shape the United States’ approach to the region in the mid-20th century. Phleger’s writing on the photograph reads: “To Laurence Gould, without whom there would be no Antarctica Treaty, with warm regards, Herman Phleger”.

How is the treaty enforced, though? The Antarctic Treaty provides for countries to inspect each other’s stations, equipment, ships, and aircraft. In a 2021 article for ABC News, Sarah Scopelianos noted that “Over the past 60 years, Australia has conducted 10 inspections in Antarctica – the most recent included visiting two facilities run by China and stops at bases run by Germany, Russia, [South] Korea, and Belarus last year.

“Checks are usually to verify compliance with the environmental and non-militarization principles of the treaty and to ensure scientific research is taking place,” she wrote. Inspections, however, are expensive, and can cost close to half a million dollars. And even after these inspections, it is difficult to enforce rules in Antarctica: Scopelianos wrote that “when South Korean and Russian fishing vessels were caught fishing illegally in the area, they avoided the consequences after their respective countries couldn’t agree on how to enforce the regulations.”

Still, as Dr Alan Hemmings, Adjunct Professor at Canterbury University, and an expert on Antarctica, said: “Antarctica is the only one of our continents where we haven’t killed each other.” If anything, the story of Antarctica so far should make us optimistic – and interested in how the Antarctic Treaty System has been so resilient. “The Antarctic Treaty has only been ratified by 54 states, far from even half of the nations in the world,” said Rothwell. “Any other country could say they are not bound by it, and decide to make their own claim. But look carefully at the parties of the treaty: they include all permanent members of the UN Security Council, as well as every country with a claim on the continent. Every critical state is a party to the treaty, none of the states that are not a party have ever manifested any interest in Antarctica, and if they suddenly did, they would face the bulk of the international community.”

“Antarctica is the only one of our continents where we haven’t killed each other.”

The Antarctic Treaty System went through several phases. Initially created to prevent Antarctica from becoming another Cold War battleground, it soon became clear its biggest challenge would be environmental. During the 1970s and 1980s, concerns about Antarctica were rarely about territorial claims, but about the risks of exploitation of the continent in disregard for its ecosystem, first through mining and then through tourism.

Claire Christian is the Executive Director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, which is based in Washington DC. “We are a coalition of NGOs that started back in the 1970s,” she explained, “when environmental campaigners discovered an agreement to mine in Antarctica was being negotiated behind closed doors. Representatives of various nations were literally sitting and smoking together to discuss the future of an entire continent with no accountability. Now, our organization is allowed in meetings, and they don’t smoke anymore! We can listen and intervene, but we take no part in decision-making.”

Her NGO played a role in preventing a scramble in Antarctica for its resources when negotiations were underway for a mining agreement called the Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities (CRAMRA). “At the time,” she said, “they all claimed there was no alternative to a mining agreement, that it was better to regulate it than let it happen with no rules. We had to orchestrate an international campaign, we argued it’s too risky to do anything in Antarctica. This is a place where you can walk through a moss bed and your footprints will have an impact for years. Fauna and flora that adapted to such extreme conditions will not recover fast.” In the end, Australia, then France, turned against CRAMRA, and that was enough to make it collapse: although it was signed, no country ever ratified it, so it has no legal value. Instead, another treaty, known as the Madrid Protocol, was negotiated in 1991, entered into force in 1998, and prohibits mining. The protocol can be revised 50 years after its ratification if a party requests it, but the outcome would require consensus between all ATCPs, making changes unlikely.

The replacement of CRAMRA with the Madrid Protocol makes for a compelling story: environmental activists stopped greedy capitalists, and governments acted responsibly. “I think the way the treaty was phrased is very clever,” Christian said, “it was a very…elegant solution.”

But, more than anything else, what’s saving Antarctica from rapacious miners is the fact that mining Antarctica is simply not a good business. In an article in The Diplomat, Nengye Liu, Associate Professor at the Center for Environmental Law at Macquarie University, noted that “[i]n the foreseeable future, it is not commercially viable to conduct mining in Antarctica.” Asked why no nation is violating the Madrid Protocol, Christian answered that, though the protocol has provisions to punish violators, its signatories includer all the most powerful countries in the world. “[S]o even if it were economically viable – which I don’t think it is in the first place – it makes it a risky venture for little profits: you’d make a lot of enemies for little economic gains!”

The development of tourism, however, tells another story about Antarctic governance. Mining has been a question since the Antarctic Treaty was signed, and thus a debate has always existed. Tourism, however, was never anticipated as a problem. It’s becoming an issue now. “Although Antarctic tourism has been completely neutralized by COVID,” said Rothwell, “with only fly-overs and no landings at the moment, the main concern about tourism has always been environmental impact. The fact that most tourists are coming by cruise ship raises concern about a potential shipping disaster.” Christian lamented that there’s no cap on the number of tourists who can visit Antarctica and how many boats can arrive there. “The industry regulates itself to a certain extent because it is in their interest to keep the place beautiful, but that’s all we have,” she said. “Nothing would stop an operator from behaving badly.” She said the Antarctic Treaty System should introduce some hard rules to make good practices that are voluntary now mandatory, like limits on tourist capacity and a ban on building hotels.

Although the existence of so many claims to Antarctica can seem worrying, Argentina and Chile are the only two claimants who have shown any serious assertiveness. The Antarctic Stations Catalogue shows the number of Argentinian and Chilean settlements dwarf that of any other country: 13 for Argentina and 9 for Chile. Only Russia, with 10 stations in total (at least 3 of which are mothballed), can match them in numbers. The nature of the Argentinian and Chilean bases is also interesting: some are more akin to villages than scientific facilities, complete with churches, museums, schools, and hotels. Both countries went as far as sending couples to give birth to the only people ever born on Antarctic soil (apparently 11 babies, all from these two countries, were born). When asked if the conflicting claims of Chile and Argentina are a problem of the past, Rothwell exclaimed: “No, absolutely not! We must keep an eye on it, because it is a significant issue! Even more because it also overlaps with the British claim and is, somehow, a part of the conflicts over the Falklands as well. These three claims have always been a source of tension. The Antarctic Treaty does not seek to resolve it, only to freeze it.” While he doesn’t think Argentina or Chile would go to war over these claims, he’s concerned about their efforts to solidify their claims.

Still, as Rothwell said, it is difficult to imagine Argentina and Chile causing much mischief by fighting to build icy schoolrooms with a handful of locally-born kids. “Other countries do assert their claim,” Rothwell added. “When Australia acquired, with much publicity, a new ice-breaking research vessel for the Australian Antarctic Division, it is supposed to be for scientific purposes but it is also an obvious way to assert their claim. Norway is pretty much the only claimant that is not proactive about its claim, and France too, although they use it to keep an eye on the region.” Christian doesn’t think anyone wants to do anything crazy. “Russia does geological surveys that are related to extractions,” she said, “but I think they all want to keep their options open, to posture. I don’t think they are seriously considering it. It’s like the territorial claims, I don’t see any claimant going to war to protect them, but they will not give them up because it would look bad. And it’s the same with fishing too, they all talk about building big boats and going fishing, but in the end they’re lucky if they build even one boat. The point is to assert your right to be part of the conversation.”

But there’s one actor in the Antarctic whose actions are particularly worrying, and that’s China.

China’s oldest base in Antarctica is the Great Wall Station in the Antarctic Peninsula, which is on the other side of the continent from Australia. The peninsula is the northernmost part of Antarctica, which makes it easier to reach and milder in terms of climate. It is also, by far, the busiest part of Antarctica, with a large number of stations, and where the two most aggressive claimants, Chile and Argentina, are building settlements. To a large extent, the Great Wall Station, which was opened in 1985, is nothing more than what many countries have in Antarctica: the full catalogue of Antarctic settlements shows that there are bases belonging to Brazil, Ecuador, Germany, Peru, Poland, Russia, and Uruguay near the Great Wall Station. Writing for Forbes in December 2020, Craig Hooper reported how “in 2016, international inspectors at China’s Great Wall Station complimented China’s impressive visitor center, but noted that concrete berms necessary to control fuel spills were crumbling apart just two years after installation.” He was, in general, unimpressed by China’s presence in Antarctica, which he called “more a myth than reality.”

The Chinese Great Wall Station (Picture Credit: User:Seleonov)

But China’s other bases are a different story. Zhongshan, opened in 1989, was the first to be located within the Australian claim. So are the two next bases, Kunlun, opened in 2009, and Taishan, in 2014. Interestingly, these three bases are not only within the Australian claim, but also within the longitudes of China itself: if China were to use its longitudes to make a claim like other claimants did, it would include the three bases. A proposed fifth base would lie further east, within the New Zealand claim.

These new stations are what concerns observers. “Compare China with the United States, who have the biggest presence in Antarctica,” said Rothwell. “The American base McMurdo is the largest on the continent, and their other base is on the South Pole itself. But the Americans are satisfied with that, they are not building any more stations. How many bases do you need anyway? Isn’t two enough?”

The American Amundsen-Scott Station, located directly on the South Pole (Picture Credit: Christopher Michel)

Despite ostensibly being for scientific purposes, some observers worry that they are gradually being used for military purposes, because Chinese scientific institutions are largely integrated with the military. This is why, for example, CSIRO (Australia’s agency for scientific research) ended five years of collaboration in Antarctica with China’s Qingdao National Marine Laboratory out of fear their work could be used in submarine-tracking technology. China is unlikely to build full-scale military bases in Antarctica, but rather would use the facilities as part of the BeiDou satellite system (China’s equivalent of GPS – which has both civilian and military use). An article in ABC News includes satellite images of the Kunlun Station that show “an unconventional setup with several antennae around the base” that hints at military purposes.

Anne-Marie Brady, a professor at the University of Canterbury and vocal critic of Chinese influence in her native New Zealand and neighboring Australia, authored a special report on Antarctica for ASPI, an Australian think-tank, in 2017, in which she noted that “Chinese and international reports commented that the new radar station would be capable of blocking the US’ polar satellites – an important military consideration. The PLA’s involvement in this activity was widely – and proudly – reported in the Chinese media.” There are many such examples of Chinese doublespeak in her paper. She also noted China’s failure to properly report its activities.

And, by the way, if you’ve heard rumors that the Antarctic Treaty may expire, China may have had something to do with that – Brady also observed how “Chinese Antarctic policymakers and academics frequently state myths about Antarctic governance, such as that the Antarctic Treaty will end in either 2041 or 2048.”

Through these actions, China is slowly undermining the Antarctic Treaty System (just as it has undermined international law to stake territorial claims in the South China Sea), which may cause it to collapse. More ominously, these actions may pave the way for China to withdraw from the treaty altogether. “One scenario is China withdrawing from the treaty,” said Rothwell. “There would be several reasons for this: not being bound means doing what they want, no obligation to respect the huge Australian claim, or the prohibition on mining, etc. And it could also lead to the dissolution of the treaty as a whole.” The withdrawal of such a major country would likely trigger a collapse of the whole system, as other countries would be reluctant to remain bound by its rules if China wasn’t also bound.

China is slowly undermining the Antarctic Treaty System (just as it has undermined international law to stake territorial claims in the South China Sea).

Such a collapse would shatter the fragile peace in the Antarctic and spark a lawless free-for-all with every country trying to grab what it can, maybe even an arms race. And, if a conflict starts elsewhere, would the Chinese bases in Antarctica become a legitimate target because they play a military role? If so, will China defend them?

In Scopelianos’ article in ABC News, Claire Christian observed that to “permanently demilitarize an entire continent was a huge accomplishment.” But as China chips away at the Antarctic Treaty System, and other countries take note, it’s worth asking how much longer this will last.