Genius and Madness

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

1/6/2019

Those who danced were thought mad by those who couldn’t hear the music.

– George Carlin

The association of genius with madness is almost as old as the idea of genius itself. Recall Alan Turing in The Imitation Game, obsessive, tormented, and driven to suicide, or the schizophrenic John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. Further back, Socrates said that the poet has “no invention in him until he has been inspired and is out of his senses,” and Plato claimed that the poetry of sane men “is beaten all hollow by the poetry of madmen.” Indeed, Socrates himself, as described in Plato’s Apology, seems a prototype of the mad genius, afflicted by a form of divine madness, possessed by a daemonic spirit, such that he courted his own execution at the hands of the state.

The Renaissance philosopher Marsilio Ficino linked genius with manic-depression. “Great wits are sure to madness near allied,” wrote the poet John Dryden, “And thin partitions do their bounds divide.” The Romantic novelist George Sand said that “Between genius and madness there is often not the thickness of a hair” – giving rise to the modern aphorism about the “thin line” between genius and madness. The Romantics, in particular, perpetuated the idea of the tortured genius – the brilliant visionary driven mad by his own visions.

The Romantics, in particular, perpetuated the idea of the tortured genius – the brilliant visionary driven mad by his own visions.

Of course, the link between genius and madness is often exaggerated. People have a tendency to exaggerate the little quirks of famous individuals into signs of madness. “We must not forget,” wrote J. F. Nisbet in The Insanity of Genius, “that trivial details in the lives of great men are recorded and made much of, and that the same symptoms in ordinary men would not be regarded as insanity.”

Another mistake is the notion that madness actually helps or amplifies genius. Whilst madness and genius do often seem to go hand-in-hand, and it may be tempting to suggest they feed into one another or to romanticize madness as a source of genius, this idea is unfounded.

Isaac Newton, for example, became increasingly mentally unstable as he grew older, culminating in a mental breakdown at 50. However, his crowning discoveries – his feats of genius – were made when he was in his early to mid-twenties and a student (and later fellow) at Cambridge, when he was relatively mentally stable. “[M]ania never brought him to the creative heights of his Cambridge years,” concluded D. Jablow Hershman and Julian Lieb, former director of the Dana Psychiatric Clinic at Yale-New Haven Hospital, in The Key to Genius: Manic-Depression and the Creative Life.

John Nash, the mathematician and father of game theory, was more than a little mad. At 30, he began to grow increasingly schizophrenic, claiming to hear alien messages. He declined a prestigious chair at the University of Chicago because he said he was planning to become Emperor of Antarctica. Eventually, he was committed to a series of mental hospitals. Though he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences at 66, he won it for his work on game theory, which he did when he was in his twenties and still relatively mentally stable.

Russell Crowe plays John Nash in A Beautiful Mind

Much has been made of the manic state in manic-depressives, some viewing it as a divine trance that generates works of genius. This is a misapprehension. The manic state increases your energy levels, but little else. It increases your output, but works of genius depend on quality, not quantity.

Cognitive psychologist Robert Weisberg noted this when he examined the work of composer Robert Schumann. “Weisberg found that Schumann’s compositional output indeed swelled during his manic years,” related Hara Estroff Marano in Psychology Today, “but the average quality of his efforts did not change” (to measure quality, Weisberg looked at the number of recordings available of a composition). “When mania struck, Schumann wrote more great pieces – but he also turned out more ordinary ones.” Mania “jacks up the energy level,” said Weisberg, “but it doesn’t give the person access to ideas that he or she wouldn’t have had otherwise.” In other words, the manic state is no more conducive to genius than ingesting a large amount of coffee.

Robert Schumann

Indeed, madness often hinders genius. “Manic-depression is no substitute for either talent or training,” wrote Hershman and Lieb, “and it can interfere with both.” Elizabeth Wurtzel, the author of the bestselling Prozac Nation, an autobiography about living with depression, once described the manic phase as being useful for writing for great stretches of time, but said that the depression phase made her waste countless hours moping – because when she was depressed she wasn’t able to do anything else. The writer Sylvia Plath, who also suffered from depression, would likely have concurred. “When you are insane you are busy being insane – all the time” she said, “When I was crazy, that’s all I was.”

Furthermore, madness is often incapacitating and crippling. It can prevent individuals from doing the work necessary to achieve feats of genius, and from showing their achievements to others. “[T]oo much madness sabotages any possible opportunity to communicate novel ideas or products,” wrote Jeffrey A. Kottler, psychiatry professor at the Baylor College of Medicine, in Divine Madness: Ten Stories of Creative Struggle. John Nash, for example, was precluded from solving complex problems in the years he spent convalescing in mental hospitals.

There is nothing to suggest that reducing or alleviating the madness of these geniuses, for example, through psychotherapy or psychopharmacology, would have reduced their creative output, indeed, Kottler argued, “it would most likely have improved the quality and quantity of their work. When you consider the number of lost days that these folks spent in drugged, psychotic, or depressed stupors, it is mind-boggling to consider what else they could have accomplished.” The evidence suggests mad geniuses accomplished extraordinary things despite, not because of, their madness.

Mad geniuses accomplished extraordinary things despite, not because of, their madness.

***

His genius and his illness were joined at the hip.

– Dr Kari Steffanson, neurologist, on Bobby Fisher

So much for what the relationship between genius and madness isn’t, but what is it?

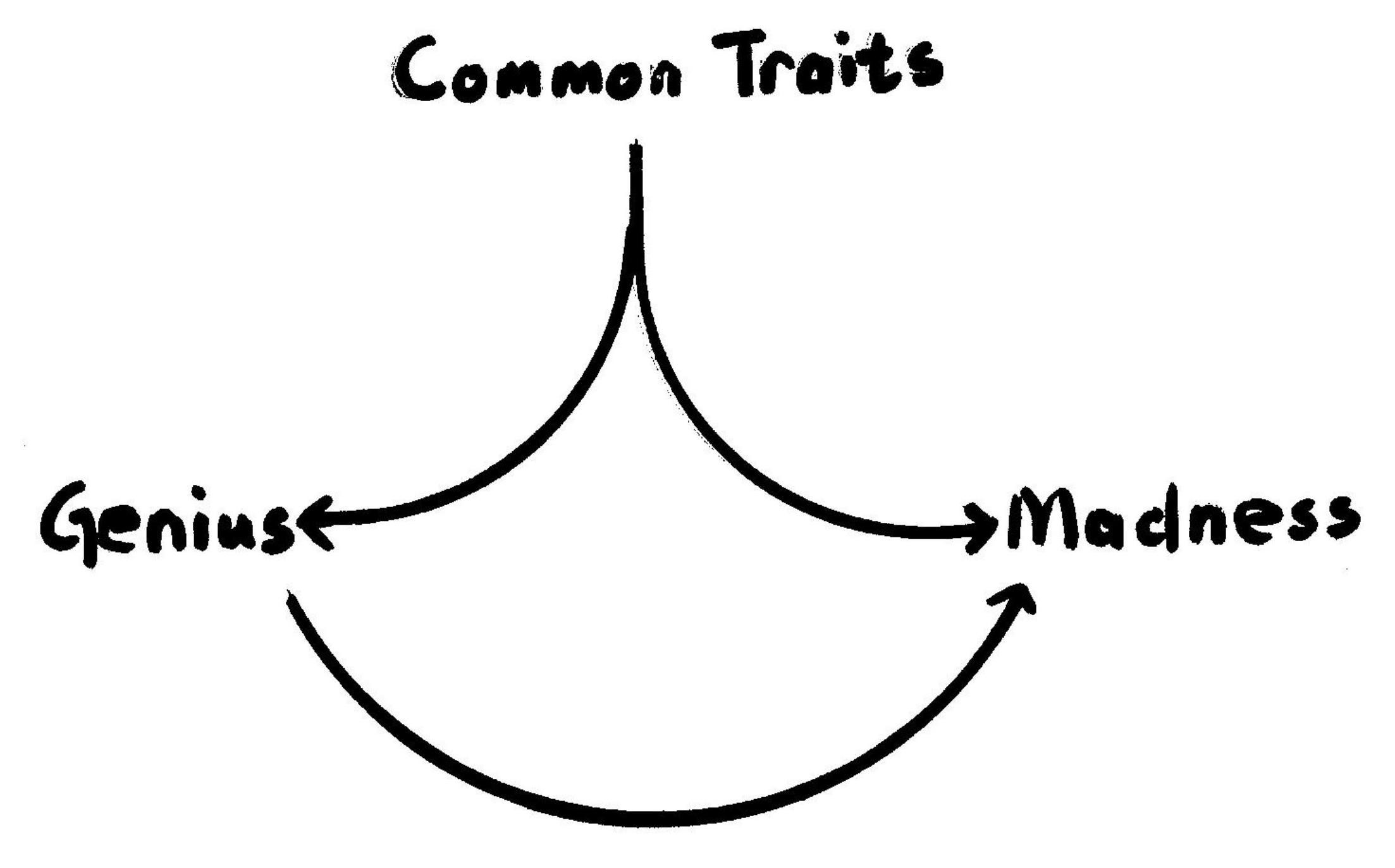

It seems there are common traits that predispose individuals towards both extraordinary mental accomplishments and behavior that is considered insane.

In Divine Madness, Jeffrey A. Kottler drew up a list of parallel symptoms of creativity (which infuses all works of genius) and madness, each with different names for similar traits. I’ve modified the list where I’ve thought of better words or examples to use.

Creativity

Madness

High energy

Sensitivity

Emotional expressiveness

Spontaneity

Risk-taking

Passion

Imagination

Vision

Big ideas

Confidence

Janusian thinking (conceiving and using contradictory ideas simultaneously)

Mania

Mood disorder

Volatility

Impulsiveness

Recklessness

Obsession

Distortion of reality

Hallucination

Grandiosity

Narcissism

Schizophrenia

Creativity

Madness

High energy

Mania

Sensitivity

Mood disorder

Emotional expressiveness

Volatility

Spontaneity

Impulsiveness

Risk-taking

Restlessness

Passion

Obsession

Imagination

Distortion of reality

Vision

Hallucination

Big ideas

Grandiosity

Confidence

Narcissism

Janusian thinking (conceiving and using contradictory ideas simultaneously)

Schizophrenia

We can see that many of the traits inherent in both creativity and madness are the same – they’re just viewed in a more positive way with creativity and in a more negative way with madness.

In particular, there are three traits that predispose individuals to both genius and madness.

The first is lack of inhibition. In his chapter “Biological Bases of Creativity” in the Handbook of Creativity, Colin Martindale, psychology professor at the University of Maine, argued that creativity is a disinhibition syndrome – “creative people are characterized by a lack of both cognitive and behavioral inhibition.” Likewise, physicians Cesare Lombroso and Max Nordau described creativity as a result of “degeneration” – the weakening of higher inhibitory brain centers. Those writers noted how this lack of inhibition could result in traits often associated with madness – like impulsiveness, morbid vanity, egocentrism, over-imagination, hypersensitivity, and aggressiveness.

Lord Byron: Mad, bad, and dangerous to know

Hans Eysenck, former Professor of Psychology at King’s College London, also noted the similarity between schizophrenics and highly-creative subjects in the remoteness of their responses on word association tasks. A study by Sweden’s Karolinska Institute supports this finding. It found that both schizophrenics and highly-creative subjects had a lower density of inhibitory D2 receptors in the thalamus. Because of this, both groups were uncommonly good at thinking outside the box. It is probable that because of this the schizophrenic subjects had more trouble than normal people getting back inside the box.

The second trait is hypersensitivity. Geniuses, especially geniuses in the arts, like writers, composers, and artists, are known to be hypersensitive. Indeed, it is this hypersensitivity that makes their work so good – because they catch what others miss and can communicate a vast spectrum of life in all its emotional complexity – they are good at inflaming the passions of others because they themselves are intensely passionate people. Composer Franz Liszt wrote of Chopin’s “overflowing nature.” “Every morning,” Liszt wrote, “he began anew the difficult task of imposing silence upon his raging anger, his whitehot hate, his boundless love, his throbbing pain, and his feverish excitement.”

George Sand (left) and Frederic Chopin (right) in a painting by Eugene Delacroix

This hypersensitivity makes creative people more sensitive to pain and suffering, which can easily lead to depression. This is exacerbated by the fact that they are also more introspective, and thus more likely to ruminate and obsess over things. “[T]heir great sensibility…permits of a keener sympathy and a deeper, clearer insight into men and things, than are granted to ordinary beings,” wrote J. F. Nisbet in The Insanity of Genius and the General Inequality of Human Faculty Physiologically Considered. “[A]t the same time disappointed hopes, failures and adversity are felt more keenly by them.” Writers and artists are, according to Kottler, therefore 12 times more likely to experience mental illnesses, and 38 times more likely to be diagnosed with manic-depression.

Even scientists and mathematicians are prone to this. Isaac Newton was known to be extremely sensitive and passionate, such that minor perceived slights against him could lead to decade-long grudges, and even death-wishes against his friends. As a boy he was often violent towards members of his household. Newton displayed signs of bipolar disorder – he seemed to vacillate between an inferiority and a superiority complex – D. Jablow Hershman and Julian Lieb found that his early notebooks “document his sadness, anxiety, fear, and low opinion of himself.”

Portrait of Isaac Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller

The third trait is the tendency to take ideas extremely seriously. Because geniuses lead such cerebral lives, they take ideas more seriously than most other people. This can lead to extreme results and behavior that the majority of society deems insane.

For example, Newton was, according to biographer John Fauvel, “incapable of tackling anything superficially,” and this extended to his Bible studies. Hershman and Lieb related how he took the Bible literally, and invested tremendous effort into studying Christianity, writing enough to fill 17 books on it. From this obsession he decided that Christianity had been deliberately corrupted in the 4th and 5th centuries, making him a heretic and a religious lunatic in the eyes of the established Church of his time. At times, this over-seriousness manifested in deviant behavior, including excommunicating his friend, Richard Bentley, for a year after they disagreed over a biblical interpretation.

***

He was made of all nature’s most dangerous ingredients: he thought deeply – he felt acutely; and for such this world has neither resting-place nor contentment.

– Letitia E. Landon, “The Bride of Lindorf,” The Vampyre and Other Macabre Tales

However, whilst madness doesn’t help precipitate genius, genius can help precipitate madness. Geniuses are the “creatively maladjusted” – they are misfits, marked out as aberrations by their own freakish intellect, and such people are more susceptible to madness because they face much more pressure from society.

Geniuses tend to change their societies. Their achievements, whether in the form of mathematical or scientific discoveries, technological innovations, or thought-provoking stories, change the world, and the way people look at it. Change inevitably creates new winners and losers, and the old winners – the established powers – often use their influence to resist change as best they can. Therefore, Galileo was persecuted by the Church, Darwin was mocked and ridiculed, and Marie Curie’s achievements were dismissed. “[M]en are not grateful to the discoverer of such truths as tend to disturb existing notions,” wrote J. F. Nisbet. “The instinctive tendency of mankind is to resent any disturbance of its placid hold of traditional beliefs, and to muzzle or suppress the disturber.”

For a genius (who is often hypersensitive), this lack of recognition, or even derision, coupled with his own inevitable awareness of his prodigious gifts compared to the limitations of others, can cause depression and confusion. “Genius feels the lack of appreciation more deeply than men of common clay,” wrote Nisbet. “[A]ny woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would certainly have gone crazed,” wrote Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own, driven mad by “the torture that the gift had put her to.” (Woolf herself suffered from bipolar disorder and ended up committing suicide.) For if the rest of the world keeps telling you you’re mad, isn’t it easy to start believing it? Who can keep his head when all about him are losing theirs and blaming it on him? Perhaps only a person of rare resilience.

Virginia Woolf

Even if the genius succeeds in getting his ideas accepted and his gifts recognized by his society, he still comes under great pressures that normal people don’t, pressures that can push him into madness, including an “overwhelming pressure to live up to earlier successes.”

A genius also often feels very lonely. Even if he’s recognized, he often remains a misfit, a freak, an individual of such sensitivity and complexity that very few others understand him – and this is true of even very well-socialized geniuses like Leonardo da Vinci and Mozart. Isolation and alienation are part of his condition. A genius, even if he attains success, is destined to be, in the words of William Wordsworth, “a mind for ever voyaging through strange seas of Thought alone.” Wouldn’t that be enough to drive many people mad?

Picture Credit: J a s o n B o l d e r o