Goodbye Merkel, and Good Riddance

By Julien Oeuillet

Staff Writer

25/9/2021

Soon, Angela Merkel’s 16-year-long tenure as the Chancellor of Germany will finally end. As a European citizen, I’m glad to see her go.

I brace myself now for an avalanche of hagiographies that are, from my perspective, entirely unwarranted. Germany under Merkel shamelessly used its weight in the European Union for its own gain, greatly damaging an institution that was created to foster common prosperity, and undermined its core values when doing so was expedient. Merkel herself postured as a stateswoman on the world stage, but constantly shunted unpleasant work and unpleasant decisions to others, and shirked her responsibilities as a major European leader.

Merkel was very skilled at marketing herself to the Anglosphere, and, because of the privileged position of the English language, she managed to appear to much of the world as a more progressive version of Margaret Thatcher. She did this so skillfully that when good things happened in Europe she got the credit, and when bad things happened someone else was to blame.

There is the tale of Merkel showing “courage” by welcoming refugees from the Middle East, but nothing could be further from the truth. Merkel forced through a plan allowing refugees into the EU with little regard for the consequences. Although Germany took in the highest number of refugees (a million of them), many of them ended up having to live in squalor in Northern France before they were allowed to cross the channel to the UK. Other European countries had to contend with the prospect of being overwhelmed by refugees trying to enter Europe and pass through to their destinations. When Merkel decided to reduce the inflow of refugees into Europe, she did so by getting Turkey to block their entry, thus “outsourc[ing] the dirty work of making its borders impenetrable,” whilst still posing as a humanitarian. This was classic Merkel: taking the credit whilst shunting the blame onto someone else and forcing others to absorb the consequences of her decisions.

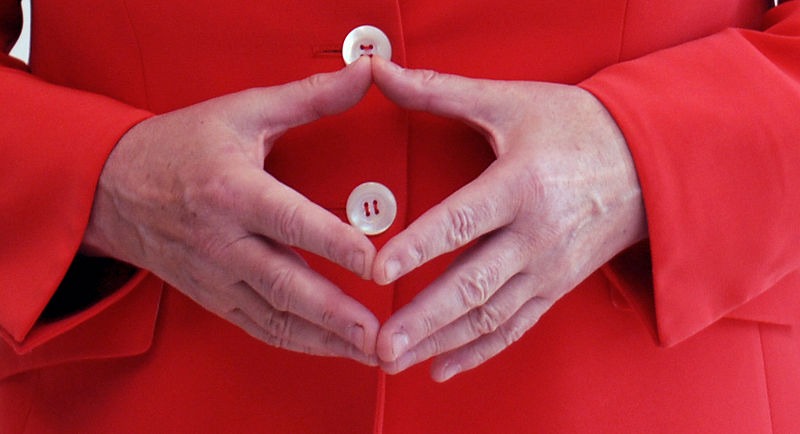

The Merkel Rhombus, Merkel’s signature hand gesture (Picture Credit: Armin Linnartz)

The refugee crisis played a major role in the rise of populism in the UK, and the resulting Brexit vote. Yet, it was a Frenchman, former French Foreign Minister Michel Barnier, not a German, who had to represent the EU in its contentious Brexit negotiations with the UK. During Merkel’s chancellorship, France did all the heavy lifting. It was France who dealt with Turkey when Erdogan was suspected of smuggling weapons into Libya and violating Greece’s territorial waters. Erdogan’s answer was to try to use Islamic solidarity to rally France’s large Muslim population to block Macron’s re-election. Where was Merkel then? And when French President Emmanuel Macron called for more European integration and a united European army, Merkel did nothing to back him up.

Southern Europe, in particular, has every reason to resent Merkel. The economic crisis of 2008 took a heavy toll on Italy, Spain, Portugal, and, in particular, Greece. When those countries hoped for European solidarity, they hit a wall with Germany, which, under Merkel, blocked the idea of using a common European bond to help bail them out. Instead, she implied that Southern Europeans were lazy and forced them to accept the bitter medicine of austerity. Yet, in the aftermath of WWII, a devastated Germany that had just embroiled the entire continent in war benefited greatly from the Marshall Plan, and was invited to join the European Coal and Steel Community (which would later grow into the EU). You would expect more generosity from a country that was forgiven so fast for destroying much of Europe.

By the time these Southern European countries were asking for relief, the salient question was not whether they were at fault for their economic crises, it was whether they should be shamed for it or allowed to emerge with a semblance of dignity. A true European leader would have recognized that fellow EU members should always try to let each other keep their dignity. She would have responded with generosity and forgiveness, the same generosity and forgiveness that was given to Germany not so long ago when it had done far worse. Instead, Merkel chose to make an example out of countries like Greece and strike the pose of the stern northern leader upbraiding the feckless southerners.

Merkel chose to make an example out of countries like Greece and strike the pose of the stern northern leader upbraiding the feckless southerners.

Eastern Europeans also have good reason to resent Merkel. Terrified by Putin’s Russia, nations of the former Warsaw Pact look to the EU for protection. Instead, as the head of the EU’s biggest economy, Merkel pushed for an agreement between Germany and Russia on the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, despite fears that Moscow could use the pipeline to blackmail the West by threatening to cut off crucial supplies of natural gas during the winter. Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, as well as non-EU member Ukraine, all opposed the deal, on the basis that it gives Russia leverage against potential EU sanctions, but Germany went ahead with it anyway.

Merkel with Putin in Sochi, 2017

In similar fashion, Merkel pressured the EU to seek an abhorrent, last minute trade deal with China in the eleventh hour of Donald Trump’s presidency. At a time when many others were distancing themselves from China for its unscrupulous trade practices and its mass human rights violations in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, Merkel pushed for the deal because it made it easier for the German auto industry to do business in China. Merkel intended for Germany to reap the benefits of this deal whilst leaving the European Commission to suffer the disgrace of dealing with Beijing. When the European Parliament rightfully torpedoed the deal due to an escalating row with Beijing over its mistreatment of Uyghurs, Merkel was nowhere to be seen. It was up to the same small EU members she offended while flirting with Putin, like Lithuania and the Czech Republic, to tell China to shove its “wolf warrior” diplomacy.

Likewise, Merkel was happy to ignore the rising authoritarianism in Viktor Orban’s Hungary and its degeneration into something less like a democracy and more like a dictatorship. Maybe that’s because German carmakers produce many of their automobiles in Hungary, with Mercedes and BMW each investing over $1 billion into building new factories there in recent years. Of course every national leader wants to help her country’s economy, but compromising the values and common good of the EU to do so is despicable and irresponsible for anyone who styles herself as a leader of the bloc, let alone of the free world.

Viktor Orban and Angela Merkel at the European People’s Party summit in Brussels in 2017 (Picture Credit: European People’s Party)

Of course, Merkel is not to blame for everything: other European economies were at fault too. Germany did not create the Greek economic crisis. When she took office in 2005, the European Union was not in the best shape and, initially, the continent welcomed her attitude: she is a calm and thoughtful leader who doesn’t rush to act. This is one reason why she was so successful in Germany: traumatized by the past, Germans are wary of demagogues. Germans are so averse to loud politicians that even the far right in Germany, the politicians of the AfD, tend to adopt a quiet image that is more reminiscent of Merkel than Hitler. This is how you get elected in Germany, and it is to the credit of German people that they vote so.

But before long Merkel’s calm attitude became little more than Machiavellianism, a quiet, cynical strategy concerned chiefly with feeding the massive Germany economic engine and steamrolling over everyone in its way whilst projecting an image of benevolence to the world. It’s no surprise that so many in the EU have been considering divorce: she was Germany’s mutti, but to the rest of us she was one heck of an annoying mother-in-law.

Merkel was Germany’s mutti, but to the rest of us she was one heck of an annoying mother-in-law.

I am a proud citizen of the European Union who believes in its capacity to foster peace, human rights, and the rule of law in my continent and beyond. After 16 years of Merkel as the Chancellor of Germany, Europe is more riven by authoritarianism, populism, and skepticism towards the EU than at any time in the past few decades, in large part due to her selfish and irresponsible policies.