How Australia's Economy Became Addicted to China

By Julien Oeuillet

Staff Writer

30/4/2021

Lately, Australia is getting increasingly assertive towards Beijing, including pushing for an investigation into the origins of COVID in China. China responded with trade sanctions on many sectors of the Australian economy, from barley to beef and coal to lobsters, as well as threatening to decrease the flow of Chinese students to Australian universities. It even had the gall to hand Australia a list of 14 grievances – which is effectively a list of things Canberra should refrain from doing to get back in Beijing’s good books. The list is nothing short of an ultimatum demanding that Australia align with China’s interests: accept Huawei’s 5G infrastructure, give up on legislating against Beijing’s influence, and shut up about China’s human rights violations and incursions in the South China Sea. As a final gesture of scorn, rather than keeping it within diplomatic channels, the list was leaked to the media.

What makes China feel it can get away with this? The answer is that Australia has allowed its economy to become dangerously dependent on China. No country would like a trade war with China, but Australia fears it more than most. In 2019 the share of Australian exports to China rose to 40%. China is by far the biggest customer of many of Australia’s key industries, including iron ore, coal, and tertiary education. Other important sectors like food and wine are also reliant on the Chinese market.

So how did Australia end up in this situation?

Peter Jennings heads the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), a think-tank that advises the Australian prime minister on foreign policy and security. “It is hard to swallow,” he said, “but our economic ties to China is the only thing that spared us the 2008 recession.” Australia made China its lifeboat in times of crisis, but Canberra was courting Beijing before 2008. Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, who first took office in 2007, and the Liberal Tony Abbott, who succeeded him in 2013, did all they could to cultivate close relations with China. Rudd himself was a former ambassador to China. “Rudd became prime minister at the precise moment when Australians discovered an unprecedented market was available to them,” said Paul Monk, an author and former head of China analysis for the Australian Defense Department, “he epitomized this optimism about China’s opening and development.” Under Rudd, Australia made big strides towards signing the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA), and his successor, Abbott, continued this policy. Jennings blames both Labor and Liberal parties for Australia’s economic dependence on China, saying that “both were driven by greed.” (Abbott himself admitted in April 2015 that his policy towards China was motivated by “fear and greed.”) And, as Jennings said, when the ChAFTA was finally signed in 2015, “no one thought they were now signing with Xi’s China and not Hu’s.”

Things only changed when Malcom Turnbull (another Liberal) became prime minister. What Turnbull found upon taking office in late 2015 was an Australia compromised by Chinese influence at every level. Richard McGregor, an Australian journalist and author of several books on China, wrote in Xi Jinping: The Backlash, that “Australia’s backlash came under Malcolm Turnbull,” who he describes as a man once seduced by Chinese opportunities but who, in office, “changed his views, disillusioned with China’s protestations of goodwill in foreign policies and its hardball tactics in bilateral disputes.”

Malcolm Turnbull (Picture Credit: Matt Roberts, ABC)

Monk concurred: “Until Malcolm Turnbull became prime minister, China had almost a free hand.” Monk said that when Kevin Rudd was prime minister, the Director General of the Australian Security Intelligence Organization, Duncan Lewis, raised the red flag on foreign influence, saying it was a bigger challenge than it had been even at the height of the Cold War, only to have Rudd dismiss this as McCarthyism. “Turnbull changed the situation when he asked John Garnaut, a consultant on international relations, to investigate and report to him confidentially about Chinese influence operations in Australia,” said Monk. “Turnbull then got foreign influence legislation through parliament, but, according to Garnaut, no meaningful budget was provided to act on it.” Still, the law against foreign influence is nettlesome enough to Beijing that it included it in its list of 14 grievances.

But efforts to turn the tide against Chinese influence by Turnbull – and his successor, Liberal Prime Minister Scott Morrison – seem belated, as Chinese influence has already penetrated into many levels of government and society.

After an Australian senator was caught taking money from a businessman linked to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), apparently in exchange for supporting China’s interests, the CCP seems to have decided that trying to influence Australia at the national level may not be the best strategy. Instead, it’s now concentrating its influence operations at the state level, since Australian states have wide autonomy, and many local governments and businesspeople make easier targets.

China is now concentrating its influence operations at the state level, since Australian states have wide autonomy, and many local governments and businesspeople make easier targets.

The state of Victoria, which has its capital in Melbourne, has been its prime target. Victoria’s premier, Daniel Andrews of the Labor Party, sparked controversy when he signed his state up for China’s Belt and Road Initative, and, in April 2021, the federal government had to invoke national interest and use a new foreign veto law to block it.

In some parts of Australia, China’s weight on local industries creates enough fear that people align with CCP policy seemingly without even being asked to. In 2018, a beef fair was held in the rural Capricornia region of Queensland, which thrives on a beef industry essentially aimed at the Chinese market. The fair offered schoolchildren the opportunity to paint the flags of their countries of origin on a cow statue as a celebration of multiculturalism. When two children born of a Taiwanese mother added Taiwan’s flag, it was later painted over at the behest of the regional council. Peter Robinson, the now-retired journalist who covered the event, recalls “we could not find any trace of a request by a consul or anything, our local council did it themselves.” To defend the decision, a regional council spokesman claimed they were obeying a national position on the One-China question, but the local member of the Federal Parliament denied any nationwide ban on the Taiwanese flag.

In some parts of Australia, China’s weight on local industries creates enough fear that people align with CCP policy seemingly without even being asked to.

Chinese influence over the mining industry is even stronger. “It is immensely disappointing to see that attraction [to] easy money at the expense of democracy has become the Aussie way,” said Jennings. “The mining industry is a big pro-Chinese lobby. In the EU or the USA, big companies are parts of more sophisticated markets where concerns such as the stealing of IP can mitigate their position on China. But in Australia the economy is much more simple, driven by resource extraction.”

Carmichael coal mine in Queensland (Picture Credit: Cameron Laird)

Mining mogul Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest is a prominent example. One of the richest men in Australia, Twiggy, as he is popularly known, has helped spread the notion that COVID originated outside China, a narrative often pushed by Beijing. Once, he helped a Chinese diplomat gatecrash a press conference by the Australian health minister, Greg Hunt, where the diplomat proceeded to push China’s narrative. Though Twiggy is given glowing coverage by the Chinese state press, in Australia, he has been called a “Beijing propaganda sockpuppet.” “Aussie businessmen have proven incapable of looking past the next quarterly report,” lamented Jennings.

Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest (Picture Credit: Mines and Money)

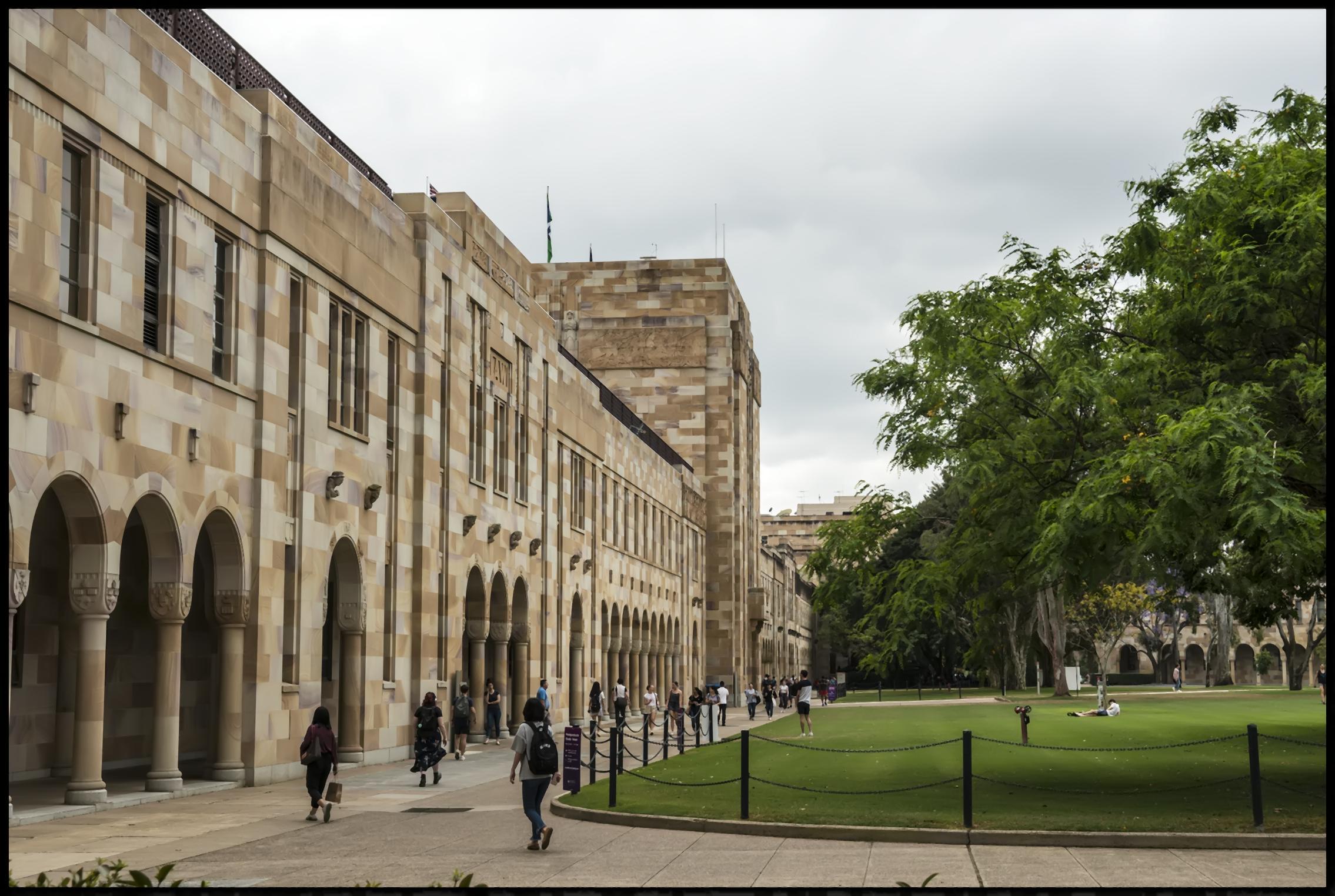

Then, there’s the higher education sector. Nationalist Chinese students are getting increasingly assertive and demanding that their universities and their professors censor themselves and refrain from casting aspersions on the Chinese government. A journalist who works at the ASPI said that such incidents are now “happening every day” at Australian universities. CCP partisans harass pro-democracy Chinese students on campus and block speaking invitations to the Dalai Lama. Most egregious is the case of Drew Pavlou, a student at the University of Queensland who protested China’s human rights abuses and used his position as an elected student representative to support the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong in 2019-20. Masked pro-CCP thugs violently attacked him and his friends as they protested, and Pavlou was branded a “separatist” by Xu Jie, China’s consul-general in Brisbane (who is also an honorary professor at the university). Instead of defending its student, the University of Queensland sided with the CCP and threatened Pavlou with a lawsuit and with expulsion for “prejudicing” the university’s reputation.

Why are universities, which are supposed to be bastions of free expression and academic freedom, so keen to compromise their principles to appease the CCP? Perhaps a large part of the reason is that more international students at Australian universities come from China than from any other country (Chinese students make up a third of international students and number around 164,000). Since international students pay much higher fees than local students, Australian universities tend to view Chinese students as “cash cows” whose fees can account for about a fifth of their revenue, and are thus easily cowed by threats from China to discourage its students from coming.

The University of Queensland (Picture Credit: John)

It is difficult to understand why Australia’s top universities, like those in the Group of Eight, couldn’t just make up any shortfall in Chinese students simply by giving those spots to international students from other countries. Every top university in the world tends to be oversubscribed and admits only a fraction of the students who apply, thus leaving them plenty of room to absorb any drop in applicants. Australian universities do not publish admission rates and share only limited statistics, making their claims that they depend on Chinese students for financial survival hard to verify. If one imagines Chinese students make up a third of the approximately 20,000 international students at the University of Melbourne, for example (as they do at Australian universities in general), a rough calculation shows that even if not a single Chinese student were to apply, the university would be able to replace them with other international students so long as its admissions rate is 67% or lower, which should easily be the case with any competitive university.[1] If this is true, then the CCP is making empty threats, but if data exists to expose its bluff, these universities have yet to provide them.

But perhaps the reason for Australian universities’ willingness to capitulate to the CCP is more personal. As Rowan Callick, a journalist and China specialist at The Australian, related: “On their visits to China, [university] vice-chancellors are usually treated with considerable respect and even deference, and the congenial nature and ease of such visits disposes them to seek to respond appropriately.” Peter Hoj, who was vice-chancellor of the University of Queensland until last year, was also a senior consultant to Hanban, the Chinese government organization that oversees Confucius Institutes worldwide, and received a $130,000 bonus from the university for bolstering ties with China, which may go some way to explaining the university’s willingness to throw Pavlou under the bus. In the state of Victoria, John Brumby, the chair of the International Education Advisory Council, was on the board of Huawei for eight years, and once wrote: “Let’s not pretend that the Chinese market — the world’s largest — is replaceable. And why should we want to replace it?” Instead, he urged developing “even deeper, stronger, and longer-lasting ties with the Chinese people.”

The result is a large lobby of powerful academics opposing the Australian federal government’s attempt to push back against Chinese influence, typically by using accusations of racism, a tactic has been used by Beijing countless times to silence criticism and is now being parroted by Australian universities. The vice-chancellor of the University of Sydney, for example, accused the Australian government of “Sinophobic blatherings” when the law against foreign interference passed. Likewise, a gallery at the Australian National University took down paintings from an exhibition because they portrayed Mao as Batman and Xi Jinping as Winnie the Pooh, ostensibly because the works were racist. In effect, Australian universities are doing Beijing’s work for it by censoring dissent and criticism, mirroring its methods and rhetoric to a frightening degree.

Australian universities are doing Beijing’s work for it by censoring dissent and criticism, mirroring its methods and rhetoric to a frightening degree.

Perhaps now, though, the tide is starting to turn. China might have overplayed its hand. For one, there are certain industries it can’t sanction, like iron ore. Australia is the biggest producer of iron ore in the world, and China has been unable to obtain enough from other sources to meet its demand. Economically, China may have played all its cards. As trade expert Jeffrey Wilson said: “there is not much they can do to Australia anymore.” What else can China ban from Australia now that it has already banned everything – except the iron ore that it can’t get enough of anywhere else?

China’s attempt to bully Australia has become so overbearing that it has freed up room for the government to fight back. “Chinese influence has been identified publicly to such an extent that Morrison has more scope to act,” said Monk. “China’s actions have been backfiring, undermining trust in China within Australian public opinion. The worst enemies of Chinese influence operations in Australia are the Chinese themselves.” A poll by The Guardian last December found that 49% of Australian respondents think Australia should become less close to China, and 62% think Australia is being victimized by China on trade rather than being itself to blame by publicly criticizing the CCP.

But there are also many prominent Australians who are likely to resist this stronger stance against China. “There are still strong forces within Australia that try to push us back to dependency on China,” said Jennings, “I do not believe this standoff is going to revert back to full dependence, but others such as some state premiers, parts of the business community, and university vice-chancellors, are going to resist this trend, and solely for venal reasons.”

As Canberra stands up to the CCP, it will have to contend with all these people who have profited from keeping the Party happy. And, whilst China may have nothing left to sanction in Australia, the longer-term effects of the sanctions that are already in place are yet to come. As McGregor wrote in Xi Jinping: The Backlash, “once Australians start losing their jobs because of Chinese economic sanctions, it is far from certain that the country and its leaders will hold their ground.” Though Australia seems to be trying to kick its addiction to Chinese money, the withdrawal will be painful.

[1] Number of international students at the University of Melbourne = 20,000

Estimated number of Chinese students at the University of Melbourne = 20,000 * 0.33 = 6,600

Therefore, for the University of Melbourne to be financially hurt if all Chinese students stopped coming, it must be unable to fill 6,600 spots even if it were to admit all the non-Chinese international applicants.

This will happen when the number of excess non-Chinese international applicants (i.e. the number of non-Chinese international applicants who were rejected) is less than 6,600.

We can therefore calculate the maximum admissions rate required for this to be the case thus.

Number of excess (i.e. rejected) non-Chinese international applicants = number of rejected international applicants – number of rejected Chinese applicants

Where the admissions rate = x

(20,000/x – 20,000) – (6,600/x – 6,600) = 6,600

20,000/x – 20,000 – 6,600/x + 6,600 = 6,600

13,400/x – 13,400 = 6,600

13,400/x = 20,000

20,000x = 13,400

x = 13,400/20,000 = 0.67 = 67%

Therefore, the University of Melbourne would be able to replace Chinese students with other international students so long as its admissions rate is 67% or lower.

Note: This rough calculation assumes that the admissions rate, x, is the same for Chinese students as it is for other international students. In reality, Chinese students have a reputation for being academically impressive, and so the admissions rate for Chinese students is probably higher than it is for other international students.

Then again, we’re also assuming that all Chinese students will obey the CCP if it tells them not to attend Australian universities. Whilst many of them probably will, in reality, there’ll probably also be many who won’t. These two assumptions act in opposite directions and so can be expected to cancel each other out somewhat.