How Progress Blinds People to Progress

By Gurwinder Bhogal

Staff Writer

15/8/2019

Picture Credit: Chase Carter

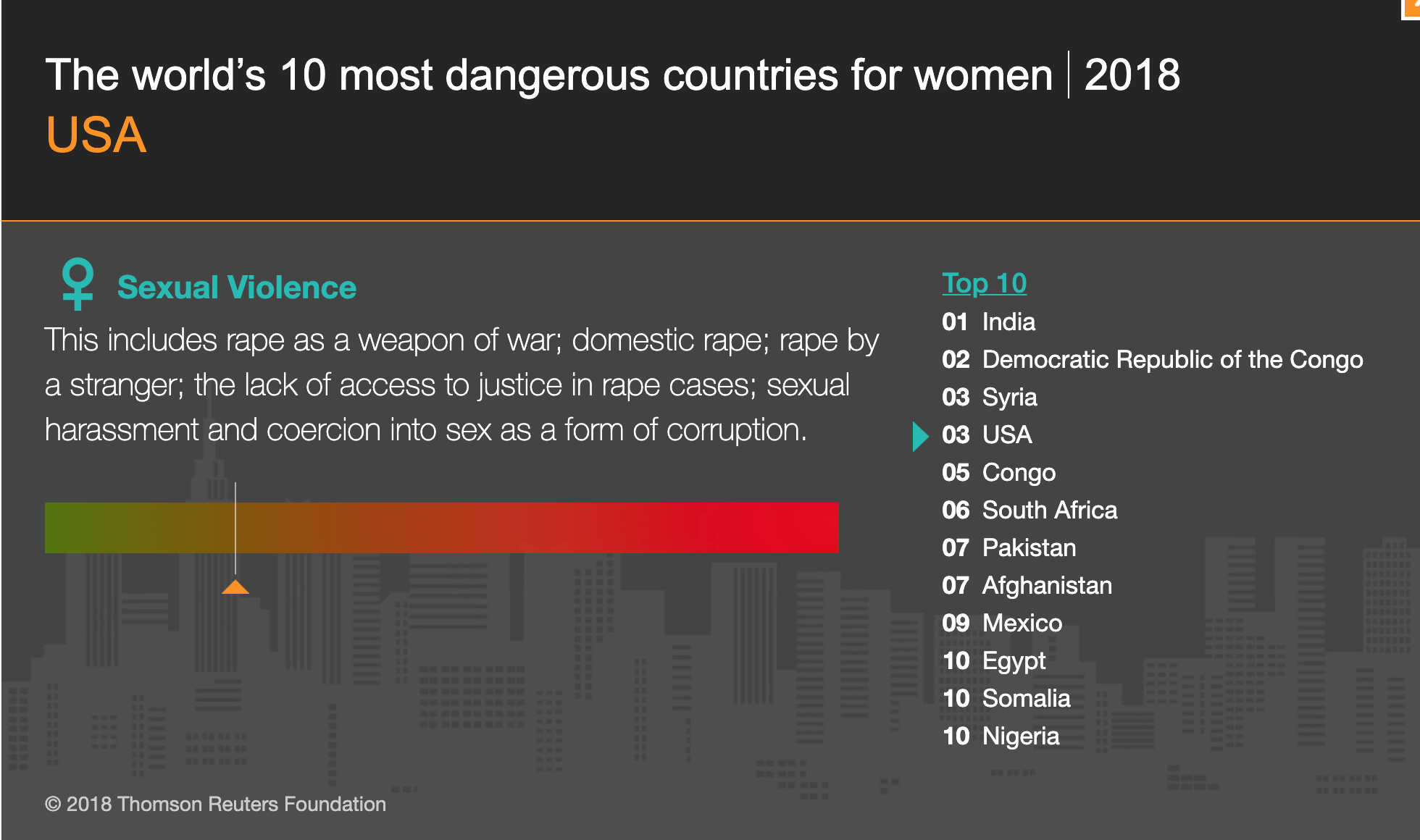

In a 2018 poll of 548 experts on women’s rights that recently went viral, the US was voted the tenth most dangerous country in the world for women. It was also voted the third worst country in the world for sexual violence, which put it ahead of South Sudan, where forced marriages are common and mothers routinely teach their daughters how to survive a rape, Afghanistan, where rape victims are often punished instead of their rapists, and South Africa, where lesbians are raped because it’s believed it can make them straight and virgins are raped because it’s believed to cure the rapist of HIV (which is epidemic in the country).

The last time this poll was conducted, in 2011, the US didn’t make any of the lists. The 2011 poll is more consistent with all the major recent analyses of women’s rights and protections, like those conducted by the United Nations, the World Economic Forum, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, all of which not only exclude the US as one of the worst countries, but frequently include it as one of the best.

The 2018 poll, therefore, seems anomalous. But what could account for 548 experts suddenly deciding that one of the countries considered safest for women had become one of the most dangerous?

The Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker has noted that there’s a tendency for people to become selectively blind to social progress, particularly in Western nations. Despite the West (and the world) making huge advances across almost all major metrics, from crime to poverty, many believe the world has made no progress, or is getting worse.

Pinker blames this phenomenon largely on what the media chooses to report. This affects judgement by exploiting two quirks of the human mind: the availability heuristic, which causes people to overestimate the explanatory power of recently received or frequently repeated information, and the negativity bias, which causes people to overweight pessimistic news stories.

This goes some way to explaining why the US is listed so high on the sexual violence scale; since most of the largest and most prominent media companies are situated within the US, cases of sexual violence in the US will tend to reach the largest global audiences.

But there’s another, deeper reason why people become blind to progress, and it seems to be a direct consequence of progress itself.

In 2016, the Australian psychologist Nick Haslam identified a pattern in the field of psychology, which he called “concept creep.” It referred to the tendency for the definitions of harms like abuse and prejudice to be gradually expanded over time.

Concept creep: The tendency for the definitions of harms like abuse and prejudice to be gradually expanded over time.

Take for example the word “misogyny.” It comes from the Greek misos (hatred) and gunē (woman), and indeed, in its original usage it was defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as simply “hatred of women.” But in 2002, something strange happened: the OED revised its definition of misogyny from “hatred of women” to “hatred or dislike of, or prejudice against women.” Note that the OED, like most dictionaries, doesn’t dictate popular usage, but follows it.

Similarly, ten years later, Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Gillard, gave an impassioned speech in which she accused Opposition Leader Tony Abbott of being a misogynist, citing Abbott’s references to her as a “witch” and someone who needed to make “an honest woman of herself.” Her words inspired changes in how misogyny is defined in Australia’s Macquarie Dictionary, which subsequently added a secondary definition of “entrenched prejudice against women.”

These examples show how concept creep can lead to expansions of the official dictionary definitions of a word. In this case, the word “misogyny” underwent “vertical creep;” that is to say, the threshold for something to be considered misogyny was lowered from hatred to mere prejudice. But concepts can also creep horizontally, to engulf newly discovered phenomena.

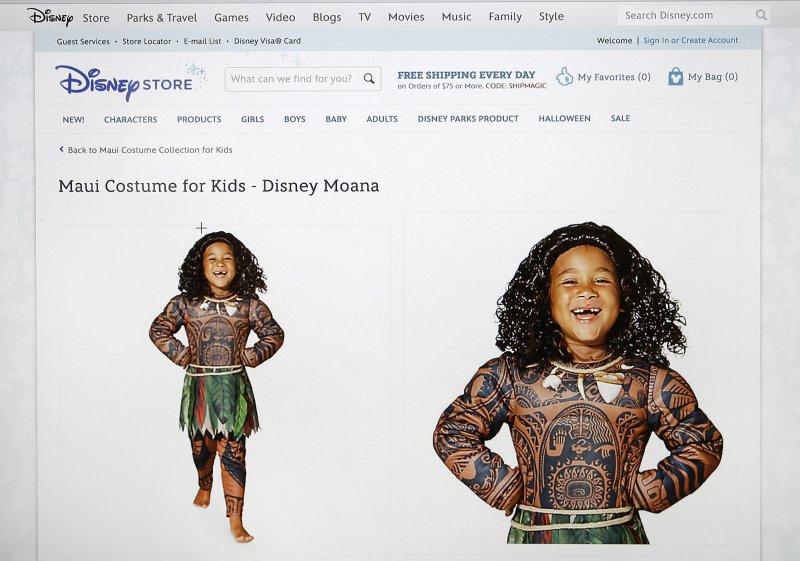

For instance, in 1986 Samuel L. Gaertner and John F. Dovidio expanded the definition of racism to include a new subtype — “aversive racism” — which was a subconscious form of prejudice that even professed egalitarians could unwittingly exhibit in their daily interactions with colored people. Since this new subtype was coined, it has itself expanded outwards, incorporating its own subtypes like “cultural appropriation.” Due to decades of concept creep, racism is now broad enough to encompass both genocide and a child wearing a Maui outfit to a fancy dress party.

Hard to imagine Martin Luther King giving an impassioned speech about this

Of course, even those who believe a Maui outfit is racist accept that it is a racism of a vastly different magnitude than, say, the Ku Klux Klan’s. The problem is, such disparities are frequently obscured by the fact that legal definitions also exhibit concept creep, causing minor incidents to be included with major ones when calculating police statistics, which are then habitually reported by media outlets without context.

As a case in point, this Guardian article claims “The vote to leave the EU in June 2016 led to a large rise in hate incidents on the streets and online.” One could be forgiven for seeing this as evidence that the UK had been stricken with a sudden surge in Brexit-related racism. What the article fails to mention is that “hate incidents” are defined so broadly by police that they include a man claiming a dog barked at him because the owner was racist and a woman upset that someone on Facebook said she looked like Peter Griffin from the TV show Family Guy.

None of this is to imply that concept creep is always a bad thing. In many cases, it is perfectly rational to expand definitions of a harm as our understanding of it increases. Unfortunately, the media’s inability (or unwillingness) to contextualise surges in police statistics in light of creeping concepts means that even reasonable expansions in definitions can lead to the propagation of dangerous false narratives.

Even reasonable expansions in definitions can lead to the propagation of dangerous false narratives.

For example, Sweden is often cited as having one of the highest rates of reported rapes in the world, and the number has been gradually rising. After a few high-profile cases of rape perpetrated by migrants went viral, a narrative began to coalesce around right-wing media outlets which tied the surge in rape statistics to Sweden’s large influx of Middle Eastern refugees, whose apparent savagery was compelling them to attack women en masse in the streets, turning Sweden into the “rape capital of the West” — a stark lesson to any who would risk their civilisation by welcoming outsiders.

While some analyses have found that migrants are disproportionately represented among those convicted of rape, it is also true that at the height of the migrant influx in 2015, the number of reported rapes actually declined by 12%. Indeed, a comprehensive investigation by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention found that the country’s first surge in reports of rape and sexual molestation (after 2005) was largely attributable to a significant expansion in the definitions of these terms that same year, which rightly classed having sex with someone who is considered too drunk to consent as rape. The investigation also found that the second surge (after 2015) was constituted mainly by nonviolent acts that occurred indoors between people who knew each other — facts that comport more with better reporting of and increased sensitivity to forms of sexual assault than with the image of migrants wantonly attacking women in the streets.

Of course, such analyses will have done little to persuade anti-immigration campaigners, who have by now undoubtedly accumulated enough cherry-picked figures to fortify their narrative of brown invaders turning Sweden into a giant harem, which remains a powerful recruiting narrative for the right.

The popular Polish magazine wSieci depicting a woman dressed in the European flag being molested by swarthy hands. The headline reads: “The Islamic Rape of Europe.”

Unfortunately, it’s not just far-right demagogues and their followers who are misled by concept creep. Experts are too, like the 548 mentioned at the beginning of this article, who collectively claim that the US is the third worst country in the world for sexual violence.

Their perception seems to have been distorted by successive expansions in the US definitions of rape and other sexual offences.

Firstly, the legal definition of rape was duly expanded in 2012 to include such offences as penetration by objects other than penises, and penetration of those too intoxicated to give consent, which led to counties across the US reporting a surge in rape cases by as much as 2,000%. Increasing the number of cases classified as rape would not only have affected statistics directly, but would also have resulted in a greater prevalence of news stories mentioning rape in the US.

Another way concept creep inflated media reports of rape is with the results of victimisation surveys, like that conducted by the Association of American Universities in 2015, which was not only subject to participation bias (victims are more likely to answer than non-victims) but also lumped together all sexual offences so that forced penetration was placed in the same category as a hand (unwittingly?) brushing against a clothed buttock, or having sex without “affirmative consent” (i.e. actively saying “yes” before each escalation of sexual activity instead of merely not saying “no”). Indeed, over half of respondents said they did not report what happened to them because they did not consider it serious enough. Yet this did not stop the AAU from announcing that 1 in 4 women had been the victim of sexual assault or misconduct on campus, a figure that immediately formed alarmist headlines in major newspapers.

If expansions in the definitions of words like “rape” by both lawmakers and independent organisations were not enough to distort media reporting and create the impression that sexual violence in the US was getting worse, the country was soon rocked by a landmark event in which definitions did not so much expand as explode.

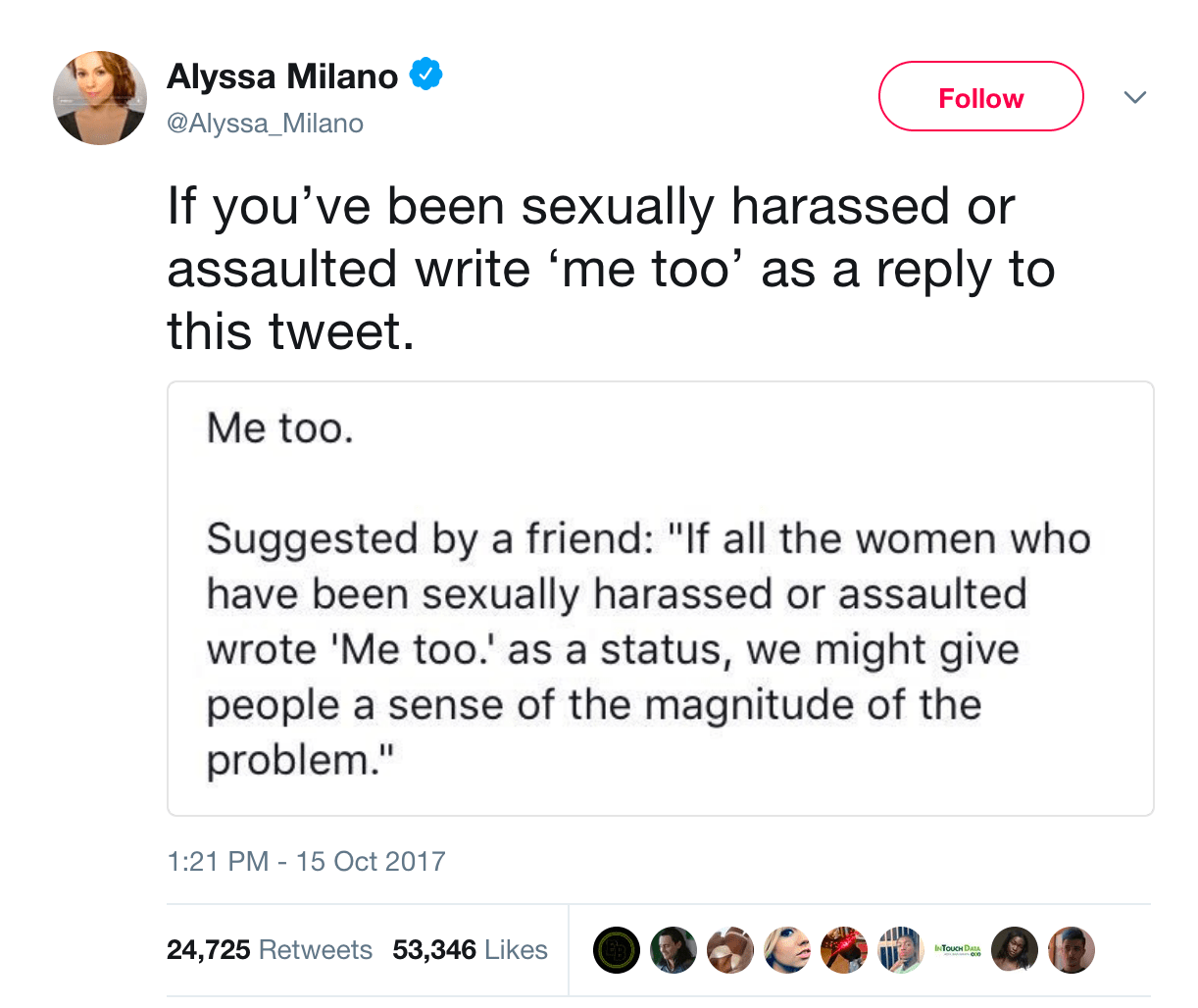

In October 2017, following the allegations of rape against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, actresses like Alyssa Milano began encouraging women to highlight the sexual abuse they’d suffered by using the hashtag #MeToo on Twitter. The resulting “Me Too movement,” as it came to be known, quickly went viral.

The tweet that sparked a revolution

No doubt, many women who used the hashtag had suffered serious sexual harassment or violence. Unfortunately, as more and more women began to add their voices to the movement, the hashtag began to suffer from concept creep. In this case the creep was particularly rapid, as the movement had no governing organisation to codify and constrain the definitions of words. Even legal definitions no longer mattered, because, suddenly, social media was judge and jury.

Soon, Me Too no longer belonged to victims of sexual crimes, but also to “victims” of awkward sexual encounters, as Aziz Ansari haplessly discovered. Cases of rape and sexual assault were conflated with cases of misread signals, leading to a mass hysteria in which the careless became as guilty as the callous and sexual violence in the US suddenly seemed epidemic.

Cases of rape and sexual assault were conflated with cases of misread signals, leading to a mass hysteria.

When looking to apportion blame for the hijacking of the Me Too movement and subsequent concept explosion of sexual violence, it is tempting to point at militant ultra-feminists, politically fashion-conscious celebrities, and opportunistic professional victims. Indeed, some analysts, like Jonathan Haidt and even Haslam himself, believe that concept creep occurs largely for ideological reasons. In their view, concepts tend to creep toward the political left (toward greater sensitivity to harm) because the institutions that dictate the meaning of words related to harm are overwhelmingly staffed with left-leaning people, whose ideology demands that they redefine words to further their agenda.

Indeed, on the surface it does appear that concepts creep toward the left. Not only can rape now include lack of “affirmative consent,” racism can now include opposition to Islam or immigration, and violence can now include mere speech. Poverty, widely measured as a relative rather than absolute figure, is by its very nature in a perpetual state of concept creep. And as for that favorite cattle-brand of the left — “fascist”— George Orwell lamented back in 1946 that “[t]he word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable.’”

Not only can rape now include lack of “affirmative consent,” racism can now include opposition to Islam or immigration, and violence can now include mere speech.

However, it is clear from the way Sweden’s inflation of rape cases was exploited for an anti-immigrant agenda that those on the right are all too happy to use expanded definitions when it suits them. Right-wingers are also guilty of directly expanding their own definitions, as evidenced by the concept creep of terms like “virtue signal” (which was originally a specific evolutionary term but has come to refer to simple sanctimony), and “white genocide” (which is an expansion of the definition of genocide to incorporate mere miscegenation).

Concept creep, then, is not specific to any ideology. On the contrary, according to recent research, it may be an intrinsic tendency of the human mind.

In experiments last year, Levari et al. demonstrated a strange phenomenon which they called “prevalence-induced concept change.” In one experiment, they showed participants a series of dots ranging in color from blue to purple, and asked them to identify which were blue. After some time, they began to reduce the number of blue dots shown. The result was that people began to expand their definition of what they considered blue.

To assess whether this finding generalized from simple concepts to complex ones, the researchers showed participants a series of faces with expressions ranging from threatening to non-threatening. After some time, they began to reduce the number of faces with threatening expressions. The result was that people began to expand their definition of what they considered threatening.

It seems that this same tendency can also be applied to societies, so that as a societal problem becomes rarer, society reacts by expanding its definition of it. Concept creep is therefore not just something that blinds people to progress; it is a direct result of progress.

The social consequence of this tendency is that civilisations become vulnerable to a kind of Tocqueville paradox, the phenomenon identified by the French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville almost 200 years ago, whereby an improvement in social conditions results in a concomitant rise in social expectations and finally a rise in social frustrations when these expectations are not met. It’s a curse similar to that suffered by the mythical Greek figure Tantalus, for whom every movement closer to the fruit was met with the fruit receding further away, ensuring he could never taste it.

Tantalus and Sisyphus in Hades by August Theodor Kaselowsky

The Me Too movement showed that the US had fallen far short of its standards — but only because its standards had risen so high. Many of the cries of the movement, like the one lamenting an awkward night of misread signals with Aziz Ansari, would not have even registered if they’d occurred in a developing country rampant with rape and sexual abuse in their original undiluted definitions. The fact that the cries of victims actual and imagined not only registered in the US, but were taken seriously enough for the Me Too movement to bloom and for Congress to respond by passing landmark legislation, is as good a sign of progress as any.

The case of the 548 experts who voted that the US is a more dangerous place for women than South Sudan therefore has an important lesson for us all; reality is based on definitions, and definitions are based on standards, which change from one country to another, and from one moment to the next. The next time the media accuses you, or your nation, or your era, or the world of getting worse, pause to wonder if it isn’t because it’s actually getting better.