I Was Falsely Accused of Sexual Harassment and Fired. I Sued, and Won.

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

2/7/2022

Note: This is an updated version of a story that was published in this magazine on the 2nd of March, 2019.

Five years ago, the Me Too movement exploded across the United States. Dubbed a revolution by its proponents, and an inquisition by its critics, it carved a swath through American society, changing campuses and workplaces, sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse, felling the guilty and the innocent alike, embroiling the blameworthy, the clumsy, and the merely unfortunate.

It sometimes went too far. What began as a commendable movement against sexual harassment and assault was soon undermined by its own excesses, in many cases going beyond protecting women to demonizing men and replacing one brand of sexism with another.

When the pendulum swings too far in the other direction, it often falls to the courts to make a correction. In the US, for example, many young men suspended or expelled for alleged sexual misconduct have taken to suing their schools, claiming they were subjected to sham investigations and unfair disciplinary hearings. Just in the past few years, there have been some 675 such lawsuits. “Of those that have worked their way through the system,” wrote Emily Yoffe, a journalist and an expert on this issue, “judges have issued hundreds of rulings deploring the star chambers and kangaroo courts to which these male students were subjected.”

As it happens, I know a bit about this. Five years ago, I brought a lawsuit like that against my former employer, Euromoney Institutional Investor, in Hong Kong, after it fired me because a female colleague accused me of sexual harassment.

Last week, I won.

***

Our story begins in 2017. I was a reporter at the Hong Kong office of Euromoney Institutional Investor, one of Europe’s biggest financial information companies. The six months I spent there were pleasant. My colleagues, on the whole, were great, and I got along with most of them, as I did with my boss, who was based in London. The standards there were boringly easy to meet, and everyone seemed pleased with my performance.

Euromoney’s office in Hong Kong

It was a lunch that would precipitate the end of my time there, though, a lunch for a colleague who was leaving, held at a nearby restaurant. I arrived late, and had to take the only remaining place at the big round table, next to a female colleague named Joey Law. I had a placemat, but no chair, so I had to drag one in. The guy to my left moved to make space for me, but Joey did not. I sat down, but my chair still couldn’t be pulled up to the table properly, and so I nudged Joey and asked her to scoot over to give me more room. She did, and I sat down and ate with everyone else. After lunch, we all returned to the office, and I returned to my work.

Three hours later I noticed I’d received an email from Joey with the ominous subject “Final Warning.”

You deliberately pressed on my waist with your hand when you squeezed into the table during the farewell lunch today, when you could just pat on my shoulder and tell me to scoot over. I found it extremely disturbing and unacceptable and I believe I have been sexually harassed by you. There is no excuse to it and I am writing this letter to serve as the final warning. If you ever touch me again, for whatever reasons, I am reporting to HR and the police.

I demand a proper apology from you as this is a very serious and offensive matter.

A few things about Joey. First, I never paid much attention to her; I didn’t work with her in any capacity, and the last time I voluntarily spoke to her was something like five months prior. Second, she’s not in the least bit attractive.[1]

A sexual harassment allegation is shocking. It’s one of those things you don’t think will ever happen to you until it does. I think anyone who’s been accused of sexual harassment should do some introspection. Presumably, no one would accuse someone of that solely from something as innocuous as a nudge. Surely there must have been some history there, some context, something that would make her suspect I had a sexual interest in her. Had anything like that happened before? Did I seem too friendly to her in the past? Did I smile too much? Did I stand too close to her? Did I maintain too much eye contact?

However, since I knew I barely interacted with her whatsoever, and regarded her only with indifference or vague dislike, the answer to all those questions could only have been “No,” and she had no sound cause to make her allegation. If she truly believed her own accusation, she was nuts, and if she didn’t, she was a liar.

Was I insulted? Yes. It’s bad enough to be accused of being a creep; I was being accused of being a creep with bad taste.

It’s bad enough to be accused of being a creep; I was being accused of being a creep with bad taste.

Still, it’s important to respond with tact and sensitivity:

What on earth are you talking about? Please don’t flatter yourself, that would never happen in a million years.

I have no interest in you whatsoever and I almost never interact with you.

You can report it if you wish, but there’s really no reason anyone would take you seriously.

I think you might need therapy.

S

After replying, I went back to my work.

***

Picture Credit: ctj71081

“Dude, that could be really serious,” a friend of mine told me over drinks that night.

I yawned. “Unlikely. No one’s gonna be dumb enough to believe her story, and even if they did, I, what, nudged her waist in a sexual manner? What the hell is that supposed to be?”

“True, not like she’s saying you grabbed her ass or something.”

I shuddered dramatically.

“Still, though. You should take steps to protect yourself. You should try to report it before she does. The first thing you should do when you get back on Monday is go to HR and tell them what happened and that you didn’t-”

“I’m not gonna do that. It’s undignified.”

“Seriously, man. Go to HR and get it on record. You need to protect yourself.”

“I’ll think about it,” I said.

***

I didn’t think about it. Or at least not for long. Why? Yes, it did seem rather undignified to be running scared over such a spurious allegation. And, the whole thing was so dumb! If we ended up having to waste time on this nonsense, it sure as hell wouldn’t be because I initiated it.

The week after, I was called in for a meeting with the human resource manager, Catherine Wong. She conveyed to me Joey’s allegation and her demand that I apologize. I explained to her why the allegation was absurd, because, for one thing, who’d be dumb enough to sexually harass someone in broad daylight in front of all their colleagues, and with the supervisor just two seats away? I also flatly refused Joey’s demand. I wasn’t gonna apologize for nudging someone to move, something people do all the time in crowded trains and buses and elevators when they need to. This is especially the case in Hong Kong – one of the most congested cities in the world – where I nudge strangers to move, and am nudged by them, virtually every day.

“Apologies are for people who have done something wrong,” I said, “and I have not done anything wrong.”

The following week I was called in to speak with Ralph Cunningham, the de facto supervisor of the Legal Media Group at Euromoney, of which Joey and I were a part. Ralph told me that Joey was demanding I apologize in writing. Again, I refused. Apologizing here smacked of appeasement, and I doubted whether it would solve the problem. I’d seen what happened at Munich; I wasn’t gonna make the same mistake. If a nudge could trigger her, anything could. What would happen a month or two later?

“What happens if in future I’m walking down the corridor and I pass her and she claims that I looked at her funny, and she makes an issue out of that?” I asked.

Ralph replied that in that case they’d look into it, depending on the circumstances.

As you can imagine, I didn’t find that terribly reassuring. And in that scenario, I’d have been in a weaker position for having apologized in the past.

Something was very odd. I’d always liked Ralph, and I’d trusted him to do right by me. Now, though, he wouldn’t even look me in the eye. He seemed frustrated and nervous. His eyes darted furtively around the room like rats trying to get out of a cage. He ended the meeting by saying he was very disappointed in my attitude on the matter.

His eyes darted furtively around the room like rats trying to get out of a cage.

I sent Catherine and Ralph a memo explaining my position and my reasons for it, but received no reply. A few days later, I was called into another meeting, this time with both of them. There, they told me they had conducted an investigation, spoken to two other colleagues Joey had brought in, and had decided to fire me.

I asked what they said, but Catherine and Ralph wouldn’t tell me. I asked how their testimony could be relevant, given that they were too far away at the lunch to have seen anything, but again they wouldn’t tell me.

Nor had they done anything to prevent Joey from tampering with her witnesses, nor given me the chance to cross-examine my accusers or to produce witnesses in my defense, if only to attest to my character. There was CCTV at the restaurant that might clarify the matter, I said. Had they tried to obtain it? They hadn’t.

I asked them what in the hells kind of investigation they’d conducted, then. Ralph told me I’d been offered a way out through apologizing, but I’d refused to take it. Catherine talked about “the responsibility to ensure our workforce is not being threatened by the threat of sexual harassment.” They told me that they’d consulted their lawyers, and under Hong Kong law I had virtually no rights as an employee since I’d been working there for less than two years and they could fire me for any reason or no reason at all, but were offering to let me resign.

When I asked for some time to consider, Ralph surprised me again by suddenly becoming a cartoon villain. “You don’t have time,” he said. “Sorry. You don’t have time. We can terminate you right now. We don’t even have to offer you resignation. We don’t have to offer you resignation. We could terminate you right now, and we’re on very firm legal ground to do that.”

So I threw their offer back in their faces. Soon after I left, many of my former colleagues asked me what happened.

“That’s so fucking stupid,” said one, when I replied.

“Man, I don’t believe you’d do anything like that,” said another. “You are not that kind of a person.”

***

I wish I could say that my story is unusual, that generally all men fired because of sexual harassment allegations are reprehensible and abusive and vile, as many of them no doubt are, but that would not be true.

The lack of due process and the low standards of proof required for sexual harassment allegations to be believed or acted upon, or sometimes even the dispensation with the need for any standards at all, mean that the innocent will often be harmed along with the guilty.

In 2017, a female journalist accused Harold E. Ford Jr., a former congressman and a Morgan Stanley executive, of sexual harassment. Ford denied the accusation, and after conducting an investigation, Morgan Stanley concluded that it was a he-said, she-said situation and found no proof of harassment. It fired Ford anyway. Morgan Stanley officials briefed on the process told the New York Times that “amid a national outcry over sexual harassment, the bank had little choice but to fire Ford after it learned of the allegation,” apparently regardless of whether he had actually done it or not.

Especially harmful are nonsensical slogans like “Believe Women” and “Believe Survivors/Victims.” The first, insofar as it means “Believe women over men” (which it usually does), is blatantly sexist. The second is circular. If someone is really a survivor or victim, that means he or she’s telling the truth about being sexually assaulted or harassed, so obviously that person should be believed by everyone. The problem is it’s often impossible or difficult to know who’s telling the truth, at least not without a careful investigation or trial, which is why we have those things in the first place. In an article in The New Yorker, Harvard Law School Professor Jeannie Suk Gersen criticized the “near-religious teaching among many people today that if you are against sexual assault, then you must always believe individuals who say they have been assaulted.” She lamented how “[e]xamining evidence and concluding that a particular accuser is not indeed a survivor, or a particular accused is not an assailant, is a sin that reveals that one is a rape denier, or biased in favor of perpetrators.”

Picture Credit: Mobilus In Mobili

But why would a woman accuse someone of sexual assault or harassment if it hadn’t actually happened? That question used to give me more pause. From my own experience, and from some other cases I’ve read about, however, I now know that the answer can be because she was mentally unstable, or because she disliked that person (or his politics) and wanted to get him in trouble, or because she wanted his job, or because she wanted attention, or because she was bored, or because she wanted to “feel part of something bigger than herself,” or because of any number of other base reasons.

This is not to say, of course, that women are not reliable or trustworthy, only that they are human, that just like men, they can be motivated by animus and self-interest; just like men, they are capable of craziness and envy and duplicity and manipulation. “My fundamental position is that women are human beings,” the author and feminist Margaret Atwood wrote in response to the Me Too movement, “with the full range of saintly and demonic behaviors this entails, including criminal ones. They’re not angels, incapable of wrongdoing. If they were, we wouldn’t need a legal system.”

Margaret Attwood, author of The Handmaid’s Tale

In March 2019, Alan Dershowitz, emeritus professor at Harvard Law School, wrote that he was being accused of sexual misconduct by two women even though he wasn’t even in the same place they were at the time the incident is alleged to have occurred. To clear his name, he called for the FBI to open a criminal investigation into his own past.

In August 2017, a woman named Jemma Beale was convicted and jailed for 10 years for falsely accusing 15 men of sexual assault. Before police realized she was a serial accuser, she had received some $14,000 from the taxpayer in compensation, and one of the men she had falsely accused had already spent two years in prison.

Jemma Beale

The solution to this problem is due process. Unfortunately, due process in cases of alleged sexual misconduct is becoming an increasingly rare commodity. Many organizations are so paranoid about being branded “soft on sexual misconduct” that they’re willing to dispense with it to avoid that perception. This seems especially bad on college campuses in the US. In an interview in February 2018, US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg agreed that in some colleges, males accused of sexual misconduct were not being given a fair hearing, which she said contravened “one of the basic tenets of our system.” In August 2017, four feminist Harvard law professors – Gersen, Elizabeth Bartholet, Nancy Gertner, and Janet Halley – released a paper titled “Fairness for All Students Under Title IX,” writing that procedures on campuses “are frequently so unfair as to be truly shocking.” For example, “some colleges and universities fail even to give students the complaint against them, or notice of the factual basis of the charges, the evidence gathered, or the identities of witnesses.” I can relate.

Particular opprobrium should go to those who call for action against people who’ve been accused of trivial things. A demand that action be taken against someone you suspect to be a rapist, even in the absence of due process, is understandable (though still not excusable). I have far less sympathy when the alleged offense itself is minor or innocuous, the sexual equivalent of a “microaggression.” Last month, Felicia Sonmez, a reporter at the Washington Post, went apoplectic and launched a public crusade against one of her colleagues because she found out he’d retweeted the joke “Every girl is bi. You just have to figure out if its polar or sexual,” on his personal Twitter account. This campaign got him suspended for a month without pay. This is a sign of how out of control the Me Too movement has gotten. Far from being something that empowers women, it’s becoming something that weakens them, that cripples them with neuroses and urges them to take offence at any perceived slight or informality. This is something that should be resisted by women as well as men. In an article in the New York Times, Daphne Merkin worried about a return to a “victimology paradigm,” in which young women “are perceived to be – and perceive themselves to be – as frail as Victorian housewives.” “Let’s not turn women into snowflakes,” former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, speaking on the same issue, told CNN. “Let’s not infantilize women.”

Faith Moore, writing in PJ Media, put it more bluntly. “Imagine a conversation in which one person says, ‘I was sexually harassed,’ and the other says, ‘Me too!’ but the first person is talking about being violently forced to submit to sexual intercourse against her will, and the second person is talking about being asked out for a drink. I feel like the first person would be justified in punching the second one in the face.”

Unsurprisingly, the excesses of the Me Too movement have caused a pushback in the courts. In an article in the New Yorker, Gersen predicted that there would be an increasing number of cases brought by men fired over sexual misconduct allegations against their former employers, claiming that a desire to implement a “zero tolerance” policy against sexual harassment made these employers biased against men, resulting in termination without proper investigation or due process, and that prediction has panned out. Indeed, that’s the very sort of claim I ended up bringing.

***

Euromoney’s lawyers were right about one thing: since I’d been working there for less than two years, under Hong Kong employment law, I could be fired for any reason or no reason at all, which explains the brazenness in terminating me on such a flimsy pretext.

What they apparently missed, though, was that there’s another raft of laws – the anti-discrimination ones – that protect employees regardless of how long they’ve been working. They make it illegal to fire anyone because of their race, their disability, and, yes, their sex.

I thought it unlikely that Euromoney would have fired a female employee if a male employee accused her of sexual harassment under the same circumstances, at least not without a proper investigation and due process, and so, a month after I was fired, I sued Euromoney for sex discrimination. I asked for it to pay me my salary from the time I was fired until I found a new job, and to write me an apology for so badly mishandling the matter. I also returned to the restaurant where we had that fateful lunch to secure the CCTV recording to shed light on what actually occurred.

I had thrown down the gauntlet. I declined to hire a lawyer because I figured (correctly) that the legal fees would probably exceed the amount I was claiming for, and opted to represent myself. I had a law degree I had never used and what information I could cobble together from lawyer friends and free legal advice clinics. My opponent, Euromoney Institutional Investor, was one of Europe’s biggest financial information companies, with in-house legal counsel and enough resources to hire the best lawyers in Hong Kong.

Fortunately, these people were idiots.

***

It would be nice to say that I won my lawsuit because I’m so brilliant, that, even though I’d never practiced law a day in my life, I conducted my case flawlessly and vanquished formidable foes. The truth is I made mistakes beyond count (though, luckily, none too serious). It didn’t matter in the end, because Euromoney’s mistakes were far worse.

The lawyer they hired, Andrew Hart, supposedly an expert in employment law, is everything you’d want in an opposing lawyer: lazy, stupid, and incompetent. He couldn’t keep track of his own witnesses and missed the deadline for filing his witness statements by about two years. His arguments were hilariously bad.[2] His documents were often so poorly drafted that it was impossible to work out what he was trying to say. No one is more grateful to him than I, but it is a great mystery to me that the law firm he heads, Hart Giles, didn’t close down within its first few months of operation. It takes the scales of justice as its logo; a more fitting one would be a fat oaf sitting on his ass.

Hart’s first letter to me, after taking instructions from Euromoney, contained the usual lawyer’s guff about Euromoney being confident in its position and the usual lawyer’s threats to make me pay their legal costs when I inevitably lost. It also claimed, bizarrely, that Euromoney had fired me not as a result of Joey Law’s sexual harassment allegation, but as a result of my “conduct during and following the investigation of that claim,” whatever that’s supposed to mean. Unfortunately for Euromoney, I’d secretly recorded my termination interview, in which I was told that I was being fired as a result of the sexual harassment allegation, with no reference to “my conduct,” which I then produced as evidence, and so it blundered headlong into a trap.

Shortly after, both Joey, the girl who accused me, and Ralph Cunningham, the supervisor who fired me, abruptly left the company, and a former colleague told me it was speculated that they’d both been fired. Later, under cross-examination at trial, the human resource manager, Catherine Wong, would claim that Joey soon resigned because she was “upset” over the incident, and that Ralph had been made redundant. Since it’s hard to believe that Joey would choose to resign after the company had fired me, taken her side, and given her everything she wanted, and that Ralph, who’d been at the company for the past 15 years, just happened to have been made redundant right after I sued, it’s more likely Euromoney blamed them for getting it into the lawsuit and fired them both. If so, this was an act of singular stupidity, as it looked like a tacit admission of wrongdoing and made a mockery of Euromoney’s pious bleating about “protecting the workforce from sexual harassment.”

Euromoney called seven witnesses,[3] but their statements (when they were finally filed) were a confused mess, often contradicting each other, sometimes even contradicting themselves. Some talked about the sexual harassment allegation, others about things that had nothing to do with it. It turned out that the two colleagues Joey brought in to support her story either didn’t witness the alleged sexual harassment, or witnessed it but didn’t seem to think it was sexual harassment, concluding only that it was rude. As for Joey’s statement, the more you read it, the more batshit insane she seemed. She claimed that after I nudged her in the restaurant she felt “nauseous for the rest of the day.” At another point, she complained that, from the day I started at the company, I terrorized her, not by interacting with her, which I almost never did, but by doing things like “walking around the office wearing a scarf” (this is true: I often walk around when I need to think, and I like scarves). She claimed she was so traumatized by my constant walking and scarf-wearing that she suffered insomnia as a result. In any case, five of those seven witnesses (including Joey) ended up deserting Euromoney’s cause and never even showed up at trial, which meant that their statements were given no weight.

The more you read Joey’s statement, the more batshit insane she seemed.

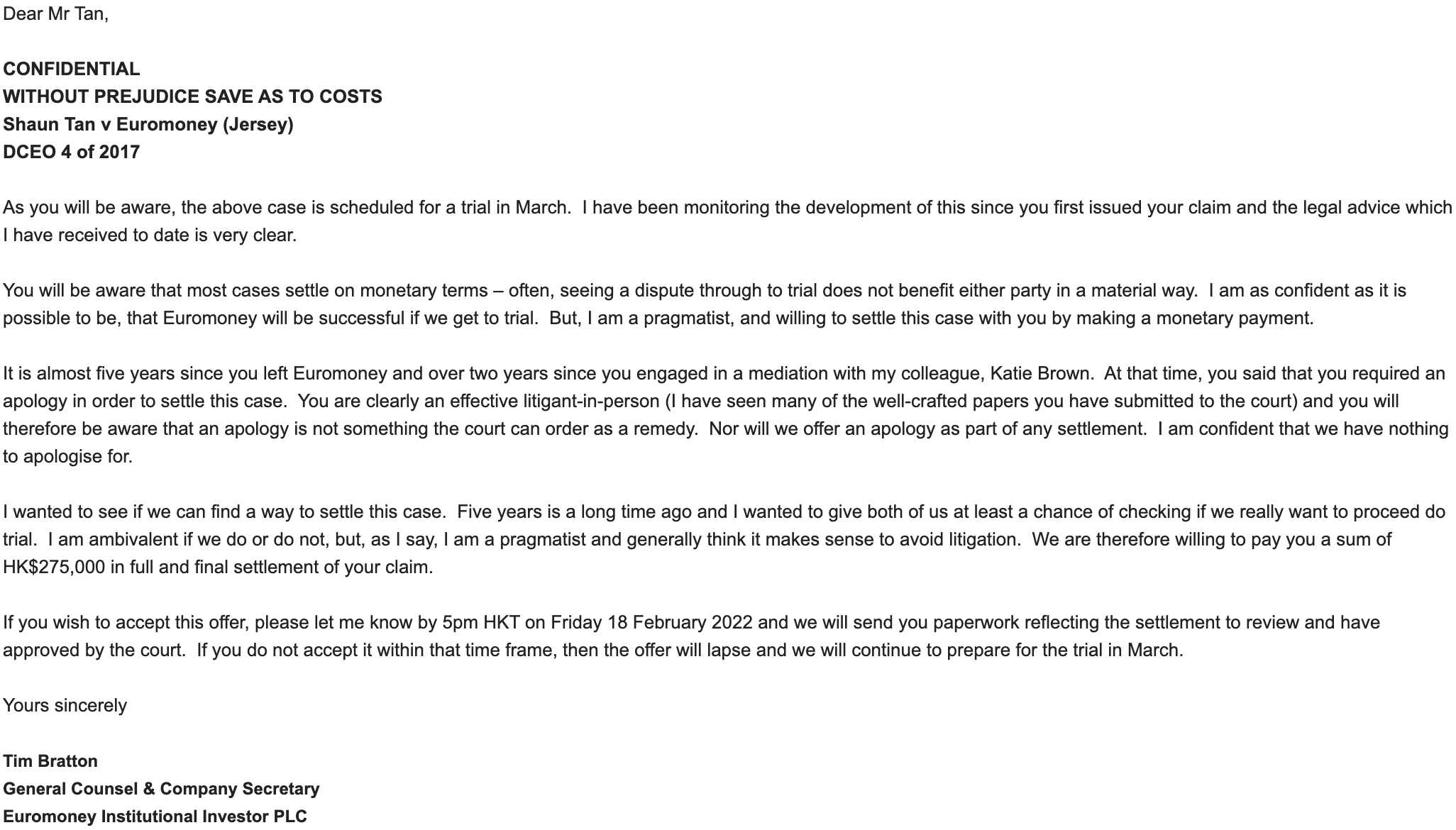

It was a long road to the trial, filled with delays, and Euromoney tried to obstruct it at every turn, whilst simultaneously offering me money to settle the claim quietly out of court. At one point, it offered me about $35,000 to drop my claim, which I rejected because it came with no admission of wrongdoing from Euromoney (and thus no accountability), and was basically just an attempt to bribe me to keep quiet.

Settlement offer from Euromoney through its general counsel, Tim Bratton

I won’t bore you with the details of the trial and the hearings leading up to it. Suffice to say that Hart proved as inept at trials as he was at everything else, and that Euromoney’s star witness, the human resource manager, Catherine Wong, came across as completely dishonest – the judge called her claims “blatantly untrue.” This was not helped by the fact that on the first day of the trial, Euromoney suddenly began claiming that I had not, in fact, been fired because of the sexual harassment allegation, but because of what it called my “offensive behavior in the office” from before the allegation, like “frequently walking around,” “frequently looking at other people’s computer screens,” and “frequently shaking my legs whilst seated at the table,” as if it had suddenly “remembered” the real reason for firing me five years later, which was completely different from the reasons it gave previously. There was no proof that management saw these things as issues (not so much as a single contemporaneous report or letter or email), or, in many cases, that they’d even happened at all, and this was obviously contradicted by contemporaneous evidence, including the recording of my termination interview, which meant that Catherine basically had to lie under oath in the face of a recording of herself saying the exact opposite thing.

By contrast, the judge noted that my testimony was “clear and cogent, and remains unshaken after cross-examination.” (This is less impressive than it might seem: it’s much easier to keep your story straight when you’re telling the truth.)

Discrimination law, at least in Hong Kong, works like this. Few people are fool enough to openly say they’re discriminating against someone, that, for example, they’re firing someone because they’re male, or female, or black, or disabled. Instead, when, say, a female employee becomes pregnant, an employer might start taking issue with her attitude or performance, or claim that she spends too long playing with her phone, and use that as a pretext to fire her whilst shielding it from discrimination charges (since only women can get pregnant, discrimination against a woman on the grounds of her pregnancy is taken as a form of discrimination against her on the grounds of her sex). Courts are aware of this, and so they’ll usually look for sudden irrational, unreasonable, or unfair treatment of employees by employers. If there’s a possibility that this treatment could be motivated by discrimination, courts then ask the employer for a satisfactory (non-discriminatory) explanation. If no satisfactory explanation is given, courts basically have to infer discrimination. Since Euromoney’s explanation was blatantly untrue and absurd, the court pretty much had to infer discrimination in my case.

Unsurprisingly, the judge decided in my favor. He declared that Euromoney had discriminated against me on the grounds of my sex and had unlawfully fired me. He ordered it to pay me about $19,000 in compensation (the full amount I was asking for), plus interest, and to write me an apology for unlawfully discriminating against me.

It had been a long, strange journey. But I got there in the end.

As I said in my closing remarks at trial:

Sexual harassment is a serious issue, and it should not be tolerated. I, too, know people who’ve experienced sexual harassment – friends, family. But the notion that I sexually harassed Joey Law by nudging her at a company lunch and asking her to move a bit so I could sit down is nothing like those cases, and is, frankly, an insult to any woman who’s really and legitimately suffered from sexual harassment, just as Euromoney’s sham “investigation” is an insult to any sense of due process, and its ever-changing lies are an insult to common sense. There are important principles at stake at this trial. That discrimination is just as bad and just as illegal when committed against a man as when it’s committed against a woman. That we’re all equal before the law. That companies cannot hide from discrimination charges by shielding themselves with blatant lies. It is these principles that must prevail.

I’m glad to see that they did.

***

What can we learn from my case?

I think it shows us how overzealous some companies have become in trying to demonstrate zero-tolerance for sexual misconduct against women. Under cross-examination, the human resource manager, Catherine Wong, admitted that Euromoney couldn’t conclude one way or another whether I’d sexually harassed my accuser, Joey Law. Surprisingly, she also said that by a certain date, Joey dropped the demand for me to apologize. What this means is that even though it didn’t know if I’d sexually harassed her or not, and even though she herself was no longer insisting on an apology, the company continued to pressure me to apologize, and fired me after I refused.

Sadly, my case also shows how much of this zeal is really just empty posturing and virtue-signaling. Recall how, after I sued it, Euromoney then apparently fired both Joey, the girl who accused me, and Ralph Cunningham, the supervisor who fired me.

How do we square this? There’s one explanation that fits the fact-pattern. Euromoney is a company that’s very protective of its image. It cared a lot about looking like a defender of female employees against sexual harassment from predatory men, such that it exhibited bias against me because of my sex, and that of my accuser, when I was accused. However, like so many other corporations, ultimately, the most important thing to Euromoney was how it looked, and so, when it turned out the resulting lawsuit was gonna make it look even worse, it blamed Joey and Ralph for getting the company into that mess and fired them too. At the end of the day, Euromoney stood not for alleged victims of sexual harassment, but for the only thing that ever mattered to it: its own image.

Euromoney’s conduct is symptomatic of corporate behavior in the Me Too age: characterized by stupidity, cowardice, faithlessness, a disinterest in the truth, and a willingness to sacrifice employees to save one’s own ass. Investigations are often witch-hunts, or exercises in ass-covering, and hearings (if they even take place) have all the fairness of the star chamber.

Euromoney’s conduct is symptomatic of corporate behavior in the Me Too age: characterized by stupidity, cowardice, faithlessness, and a willingness to sacrifice employees to save one’s own ass.

Thing is, no one benefits from this, save for the liars and extortionists who make false allegations. Not companies that damage their own morale and lose out on good employees because of spurious charges, not men who have to worry about losing their jobs over baseless accusations, not even women or the Me Too movement itself.

God knows there’s a long history of sexism and injustice towards women in the workplace, but how do we benefit from exchanging one brand of sexism and injustice for another? No one, male or female, should have to put up with sexual harassment, but spurious allegations make a mockery of everyone who’s ever had a real claim, and all those who’ve fought for those claims to be taken seriously. False or ridiculous claims give feminism a bad name and erode the movement’s credibility, and those who demand that we uncritically believe them would do well to recall what happened to the boy who cried “Wolf.”

Things didn’t turn out so well for him

“These are scary times, for women as well as men,” wrote Daphne Merkin in the New York Times. “There is an inquisitorial whiff in the air […] Next we’ll be torching people for the content of their fantasies.” “You have chiseled away at a movement that I, along with all my sisters in the workplace, have been dreaming of for decades,” said former CNN anchor Ashleigh Banfield, speaking to comedian Aziz Ansari’s anonymous accuser, “a movement that has finally changed an oversexed professional environment that I, too, have struggled through at times over the last 30 years. All the gains that have been achieved on your behalf and mine are now being compromised by allegations that are reckless and hollow.”

Ashleigh Banfield

On a brighter note, courts are starting to recognize discrimination against men when it occurs in sexual misconduct cases. During the trial, Euromoney suggested that my reply to Joey denying sexually harassing her (and telling her not to flatter herself and that she might need therapy) was rude and constituted “mental harassment” against her, which factored into the decision to fire me.[4] I suppose it was quite rude, but it was in response to her rude and insulting accusation of sexual harassment against me. The judge took this point. Whilst he found no evidence to suggest that my reply played an important role in Euromoney’s decision to fire me (which it didn’t), he noted that both Joey and I had used strong language in this instance, and wrote that, if my reply had played an important role, this itself would have constituted evidence of pro-female bias on the part of the company – since only one of us (the male) was being punished for the strong language.

Courts are even recognizing such discrimination in cases where an organization’s motives are understandable. In the 2016 US case of Doe v Columbia University, for example, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that an institution’s motivation “to favor the accusing female over the accused male,” in order to shield itself from lawsuits or criticism for not protecting women from sexual assault, could be evidence in itself of unlawful sex discrimination against males.

How, then, should we strike the balance between protecting women from sexual misconduct and being fair to the men who are accused of it? The solution isn’t that difficult. It’s just respecting the rights of both the accuser and the accused, and recognizing that respecting one doesn’t diminish the other. A company should listen to allegations and take the most stringent measures to prevent suppression, and, that most despicable of things – retribution. The company should then evaluate the allegation. If it sounds serious, it should conduct a professional investigation, giving the accused the opportunity to hear and challenge evidence or testimony against him, and to produce his own evidence and witnesses in his defense. It should then weigh the claim as a whole before coming to a decision. It shouldn’t be afraid to take action where such action is appropriate, nor should it be afraid to dismiss a claim it finds has no merit. If it punishes someone, it should do so knowing it’s right, after having taken all reasonable steps to ascertain the truth, not out of fear or a desire to project an image of “zero tolerance.” The presumption of innocence and due process aren’t just legal concepts – they’re the foundation of any free and just society.

The presumption of innocence and due process aren’t just legal concepts – they’re the foundation of any free and just society.

Indeed, maintaining standards of proof makes for stronger cases and a stronger Me Too movement. “In this national ‘just believe’ the accuser moment, it’s important to remember that part of the power of the recent accusations against movie producer Harvey Weinstein and so many others is that they are backed up by meticulous reporting that has provided contemporaneous corroboration,” wrote Emily Yoffe in Politico.

The Me Too movement, on the whole, has probably still done more good than harm (though that gap is shrinking). To stay on the right side of that equation, it will have to check its own excesses. Successful revolutions are the ones that respect fundamental rights and bring people together to create lasting positive change, not those that devolve into reigns of terror. “If men and women of goodwill could work together, they can make historic progress in the fight against harassment and abuse,” said American Enterprise Institute scholar Christina Hoff Sommers in her vlog, the Factual Feminist. “But to succeed, the movement is going to have to channel its outrage and confront its own excesses.”

Earlier, I wrote that women are just as capable of succumbing to base motives as men. But they’re also at least as capable of strength, maturity, and wisdom – and from that comes true power. A powerful woman does not need or want to be believed or judged based on her gender, but on the content of her character, and the merits of her ideas and arguments. She does not fear sexuality. She calls mountains “mountains” and molehills “molehills.” She does not put up with harassment or abuse, but neither does she demand someone’s head over some trivial bullshit.

It is this ideal of feminism that must endure.

Joey Law has not responded to a request for comment.

Catherine Wong has not responded to a request for comment.

Ralph Cunningham has not responded to a request for comment.

Tim Bratton has not responded to a request for comment.

Andrew Hart has not responded to a request for comment.

Euromoney has not responded to a request for comment.

[1] Yes, yes, I know it’s possible for unattractive people to get sexually harassed too, it’s just a lot less likely compared to attractive people. In the same way, it’s possible for a cheap plastic watch to get stolen, it’s just a lot less likely that someone would want to steal it compared to, say, a gold Cartier. And since this was a he-said, she-said situation, the balance of probabilities (likelihoods) is all anyone else has to go on. (If you don’t believe me, go to any bar or nightclub and observe how much more often attractive women get approached than unattractive ones.) Beautiful people have many unfair advantages in life; “more credibility when accusing someone of sexual misconduct against them” is just another one. C’est la vie.

[2] He repeatedly tried to claim that companies could fire employees for illegal reasons so long as they gave them notice and paid them their severance pay under their contract. One of his first arguments was to claim that I couldn’t sue under Section 5 of the Sex Discrimination Ordinance, which forbids discrimination against women, because I’m not a woman. When the judge asked him if he’d read Section 6, which says that everything in Section 5 applies equally to men, his response was “Oh,” before standing in a state of catatonic shock for, like, the next ten seconds. This basically wiped out half his argument that day in an instant and showed he hadn’t even bothered to read the statute his client was being sued under properly. Priceless.

[3] Conspicuously, Euromoney never called its then-Asia CEO, Tony Shale – apparently the highest-ranking person who made the decision to axe me – as a witness, presumably because he was considered too important to risk perjuring himself.

[4] Incidentally, this also contradicted Euromoney’s new claim that I’d actually been fired because of my “offensive behavior in the office” prior to the sexual harassment allegation. They never could get their story straight.