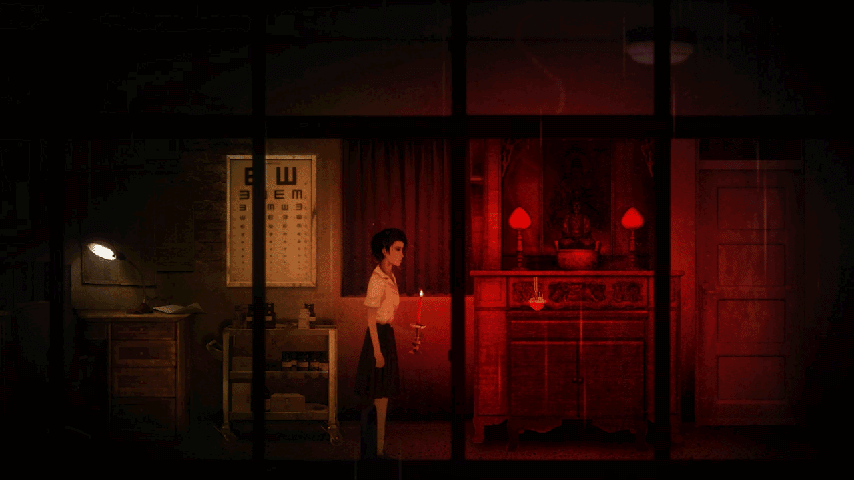

In the videogame Detention, you play as two students, Wei (a boy) and Fang (a girl), in a Taiwanese middle school in the 1960s. Early in the game, Wei vanishes, leaving Fang to fend for herself in the haunted building. Its brutalist architecture, damp with humidity and covered in disturbing scribblings that sometimes look like dried blood, soon comes to seem less like a school and more like an extermination camp. Classrooms become jails, or charnel houses, filled with corpses. Ghouls, who look strangely like Fang herself, attack her. The ghouls’ skinny bodies are stretched upwards, spines broken, heads dangling, overgrown hair covering their faces.

The terror in Detention comes from the fact that you play through it. Developed by the Taiwanese studio Red Candle Games in 2017, Detention has been carefully written to be a narrative game and not just a novel or movie adapted into an interactive form. Before long, you come to identify with Fang, you stop thinking of her as a character you’re playing but as yourself: you are lost in the labyrinth, disoriented as the game changes what lies behind the door you just came through. This is the magic of narrative videogames: they make you live the stories.

In the game, your primary means of defense against the monsters is to hold your breath, as this makes you undetectable to them. You control characters by left-clicking on where you want them to walk, but if you right click, the character will cover her mouth and hold her breath. When Fang holds her breath, the screen slowly blurs and a sound effect similar to a ringing in your ears starts playing, as she gradually suffocates. A movie could do the same. But in the game, you feel it, the tension creeps up your finger on the mouse and the adrenaline rushes through you as you try to get past the monsters before you run out of breath.

When you, as Fang, enter the school nurse’s office, you find a medical report indicating a student received monstruous injuries to the limbs and head. At first, you suppose that this was caused by the monsters, but as you wend your way through the game, you are given more clues which point to an even darker conclusion: the student was tortured by the police.

You see, Detention is set during the White Terror in Taiwan: the 38-year period when the island was under martial law, and people there were brutalized by the dictator Chiang Kai-shek and his successors in the Kuomintang Party. After their defeat at the hands of Mao Zedong’s Communist forces, Chiang and his followers retreated to Taiwan and ruled it with an iron first. Taiwanese people would only emerge from this dark period and start to know democracy in the 80s.

As you progress through the game, the ghosts and ghouls will take a step back, and the danger will come not from supernatural creatures, but from the government. The haunted school becomes an allegory of the terror inflicted on Taiwan by the Kuomintang (KMT). Lost and afraid, you desperately search for ways to escape, and in the process you piece together fragments of the story, a story heavy with the unmistakable stench of dictatorship.

The victims of Chiang’s fascist regime are not just students, but teachers and other school staff. Mr Kao, the alcoholic former soldier who now serves as the school’s concierge, may not have been taken by ghosts but by the party he loyally served but fell out of favor with. Ms Yin, the young woman who appeared as your teacher early in the game, may not have been killed by ghouls but by the government and its representative, Mr Bai (literally, Mr White).

Called The Instructor, and clad in a military uniform, Mr Bai is ubiquitous in the game and is feared by all: his signature on bloodstained flyers asking students to report any suspicious “‘Communist’ activity” to him. At the beginning of the game, characters speak of him as a killer and mock his martial tone; later a ghoul that resembles him chases you down a corridor. Mr Bai, the Kuomintang equivalent of a Communist political commissar, the Party’s eyes and ears in the school and the enforcer of its iron rule, soon appears as the game’s real villain.

The creators of Detention used the game as a vector of culture to express the unique history of their country. They also dug into their own traditions: the monsters are reminiscent of the “hungry ghosts” of East Asian legend (which are said to wander the earth aimlessly after a violent death or an evil life), Taoist talismans ward some places in the school and a Taoist altar is the sole anchor of hope for Fang (you can only save the game by praying at an altar), and you encounter traditional Taiwanese puppets and other bits of Taiwanese folklore. But above all else, the team at Red Candle Games wanted you to learn about the White Terror.

The school’s gory setting suddenly makes sense: these corpses with bags over their heads, these chains covered with blood, the screams and sounds of bones cracking, are hallmarks of a jail where political opponents are tortured. As you reach the halfway-mark of the game by crossing the schoolyard to a second building (and walk in front of an ominous statue of Chiang), Detention is no longer a horror game, but a survival game set under a totalitarian regime.

Detention is a teenager’s story. Fang and Wei are not yet 18. In the second part of the game, Fang suddenly remembers what happened before the supernatural invaded her school – things she wanted to forget, and that the haunted setting now forces her to confront. Opening classroom doors, you now find yourself in a simple bedroom filled with 1960s laminated wood furniture and geometric patterns on the wall. The ghosts are now your parents, the creepy sounds are their screams, as you are transported back in time into a troubled childhood where your once happy and united family is torn apart by abuse and infidelity. Ultimately, Mr Bai’s terrifying ghouls take your father away after your mother informs the police about his political “crimes” in revenge for him cheating on her. Fang is (you are) a traumatized child.

Fang’s broken family

Your journey into your past also takes you into your relationship with the school’s counsellor, Mr Zhang, who, to you, represented the only light in the bleak tableau. Subtly, through little messages and the solution of puzzles, you feel Fang’s growing desire for the only adult who seems to care about her, who seems to guide her instead of punishing her, you experience her first love as she loses control of her youthful heart and falls for him. When your teacher, Ms Yin, finds out about this, however, she confronts Mr Zhang for his inappropriate flirting and forces him to separate from you: suddenly the walls around you that started to look rosy go back to their bare, moldy, and oppressive form, and you are flung back into the nightmare.

And that is the most horrifying piece of the puzzle: Fang wanted revenge on Ms Yin for this, and this young girl’s fury at love destroyed is more terrible than the dictatorship, more terrible than all the supernatural monsters. The reason why you, as Fang, are trapped in a demonic school where everything seems to torment you is because, like your mother before you, you, in your rage, pushed others into the claws of the Kuomintang police. In the final stage of the game, you are offered Fang’s most shameful memory: once she discovered Ms Yin was the ringleader of a clandestine book club where censored texts were studied by a few selected students, Fang ratted on her to Mr Bai. Ms Yin was arrested, and the students ended up tortured and jailed – among them her unfortunate friend, Wei. Fang is not the kind girl you first thought she was, and what you are playing through is the purgatory into which she has been condemned, constantly being haunted by reminders of the suffering she has caused. As Fang is told by Yin’s ghost at the end of the game: “transforming into a pitiless patriot was easier than you thought, right?” The biggest monsters in Detention are ordinary humans, and the biggest horrors are what we can do to each other given the chance.

In the early history of videogames in the 1980s, small teams of developers could easily take the risk of creating weird and experimental games like this. By the late 1990s, the rise of 3D graphics and more advanced technologies made creating video games so prohibitively expensive that it was out of reach for everyone but a handful of large studios, who were also less daring in their costly ventures. In the last decade however, pre-made game engines and accessible graphic design tools made it again possible for small players like Red Candle Games to take a risk with a game that challenges conventions.

Detention reached more players than any book would have. Gaming website VGChartz estimated that the game sold 244,750 copies in its first year, and another website, SteamSpy, placed the number of owners at over 500,000. Even these estimates do not account for those who acquired the game on Nintendo Switch rather than PC. The size of the videogame industry is valued at over $300 billion per year – more than the music and movie industries combined. Detention may be more important than any book, song, or movie on the Taiwanese White Terror. The Harvard-Yenching Library, which hosts Harvard University’s collection of East Asian books, has elected to preserve Detention, as well as Devotion, Red Candle Games’ subsequent production. Yet most media outlets outside the specialized videogame press barely talk about it because, despite being such a powerful narrative tool with such a large audience, videogames are still not taken seriously.

***

Detention was adapted into a movie in 2019. It developed the romantic tension between Fang, Wei, Zhang, and Yin. It was hard for the director, John Hsu, to simultaneously portray both the horror of the supernatural world and the White Terror. He was more successful at the latter – CGI monsters mostly served to underline the cruelty of Kuomintang rule then. The movie also does an excellent job of making Instructor Bai the all-encompassing villain, his character expanding into a sort of arachnean spirit whose malevolence literally rots the walls of the school.

Gingle Wang plays Fang in the movie

It is probably a testimony to my love for Taiwan that even when the island is depicted as a horror setting I still feel warmth inside when I see it. Then again, Taiwan came into my life precisely as I left Africa behind, moving away from the smell of death, violence, and fear, to a wonderful country – wonderful if only because this is where a gem like Detention can be made. Since I’ve married into a Taiwanese family, I’m able to tap my relations for memories of the White Terror and reflections on Detention. They said Detention accurately depicts teenage life in that dark time (in the game, you can make Fang and Wei interact with some writings in the school and see them disparage the education they receive, laugh at the propaganda they are taught, and express confusion that they have to learn the name of every Chinese province). They told me how they had to salute the flag every morning before entering the classroom, how there was a political apparatchik like Mr Bai who could persecute you if you strayed too much from the party line, how everyone lived in fear, constantly. They also spoke of how different that time was from Taiwan today, which reinforces their conviction to resist aggression from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) – who would reverse all the progress their country has made – at all costs.

***

I often say the scariest movie I know is Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, because each time I re-watch it, the dystopia it depicts seems a bit more realistic. But as I see Taiwan, and the rest of the world, come under increasing threat from the same kind of monsters we see in Detention, but in a CCP uniform instead of a KMT one, I can’t help but think Detention may be even scarier than Brazil.

Detention was Red Candle Games’ first production. In 2019, the company built on its success to release a new game: Devotion. The plot is similar to Detention’s, involving a teenage girl who tries to prevent her parents from splitting up by praying to spirits, only to unleash forces beyond her control. Though set in the 1980s instead of the 60s, from its trailers, it seems equally gloomy and rooted in Taiwanese history and culture. But its trailer is all I was able to access, because it was swallowed by hungry ghosts.

Devotion was offered on Steam, the world’s largest videogame platform. Owned by American company Valve, Steam boasts one billion accounts, and is estimated to make up 75% of the global PC gaming industry’s total market share.

As soon as the game was out, though, mainland Chinese players quickly discovered a hidden message: in a room in the game is a talisman, and written on that talisman in tiny characters are the words “Xi Jinping Winnie the Pooh moron.”

As a result, Devotion was subjected to a concerted attack by Chinese netizens, many of them likely members of the CCP’s 50 Cent Army. And they won.

Steam’s ranking system allows players to upvote or downvote a game they played, which affects its position on the platform’s recommendation system. Being review-bombed kills a game’s ranking. This would not have been too much of a threat to an established game developer whose vast fan base was waiting eagerly for its latest release, but it was very damaging for a small studio like Red Candle Games. Although it was obvious the downvotes were made in bad faith, and for political reasons instead of the quality of the game, Steam did nothing to intervene and let Devotion’s ranking sink. Although Red Candle Games removed the reference to Xi and apologized profusely, the online Chinese mob was not placated. Later, Devotion vanished from Steam entirely under circumstances that remain unclear.

Since then, Red Candle Games has struggled to distribute the game through other platforms, regularly announcing it will be available soon. Steam, however, capitulated to entities who were obviously misusing its platform. Videogame media did not show Red Candle Games any support either. Popular website Kotaku called the game “controversial.” Another site, Eurogamers, reported the facts without any criticism of Steam, concluding that Red Candle Games “got some way to go before it gets Chinese players back on-side.” PC Gamer similarly gave a terse summary of the events without any word against Steam or the bad-faith Chinese reviewers. There is actually nothing controversial about a game that mocks Chinese President Xi Jinping, and while it is easy to know why Steam was so spineless against Chinese bullying, it remains a mystery why these videogame media outlets were too gutless to say anything against it.

In short, a creative and daring studio that used the videogame medium to tell interesting and important stories that made people think was silenced on an American platform by the mindless zombies of a totalitarian dictatorship that vowed to destroy Taiwan and drag it back into tyranny, all with nary a harsh word from Western media outlets. The biggest videogame platform in the world is being dictated to by a system that produces such masterpieces as a game where you need to clap your hands to Xi Jinping’s speeches, and at the expense of developers who show us exactly the kind of monstrous regime we should expect under Xi. Like in a modern-day version of Detention, where people had to teach and read forbidden books in secret, fearful of the authorities, those wanting to express ideas forbidden by the Xi regime in videogames, and those wanting to play those games, have to fear a ubiquitous tyranny that can chase them through the corridors of our connected world, burning their games like it once burned their books. This is Halloween in 2021 and you can’t even make a videogame without having to hold your breath and hope the monsters don’t notice you.