In Praise of Inefficiency

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

22/3/2020

Natalie Portman as the Black Swan

Perhaps one COVID-19 casualty will be the obsession with efficiency. If so, no one should mourn it; after all, it helped exacerbate this crisis.

A prime example of this was US President Donald Trump’s 2018 decision to fire America’s entire pandemic response chain of command, which was responsible for coordinating between different agencies to combat pandemics, a decision that leaves the country woefully unprepared to face the coronavirus. “[I]t is clear,” wrote Beth Cameron, a former director in that team and now vice president for global biological policy and programs at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, “that eliminating the office has contributed to the federal government’s sluggish domestic response.” Trump also cut the disease-fighting operational budgets of the Centers for Disease Control, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Homeland Security, and the National Security Council.

Trump defended these cuts by appealing to efficiency. “Some of the people we’ve cut, they haven’t been used for many, many years, and if we ever need them we can get them very quickly rather than spending the money,” he said. “I’m a business person, I don’t like having thousands of people around when you don’t need them.”

Trump defended firing America’s entire pandemic response chain of command by appealing to efficiency.

It’s easy to put this mistake down to Trump being an idiot and a bad businessman as well as a bad president, but this sentiment is very common amongst businesspeople, who often pride themselves on their ability to cut spending by excising non-essential departments or personnel, to realize the most profitable allocation of resources, and to squeeze every ounce of productivity from the system (these are also the very qualities touted by businesspeople who run for public office). The presence of shortsighted shareholders (i.e. most shareholders) who don’t see beyond the next quarter and who berate management for any failure to optimize their operations only encourages this. Many businesspeople also consider it efficient to be highly leveraged because that enables you to maximize return on capital.

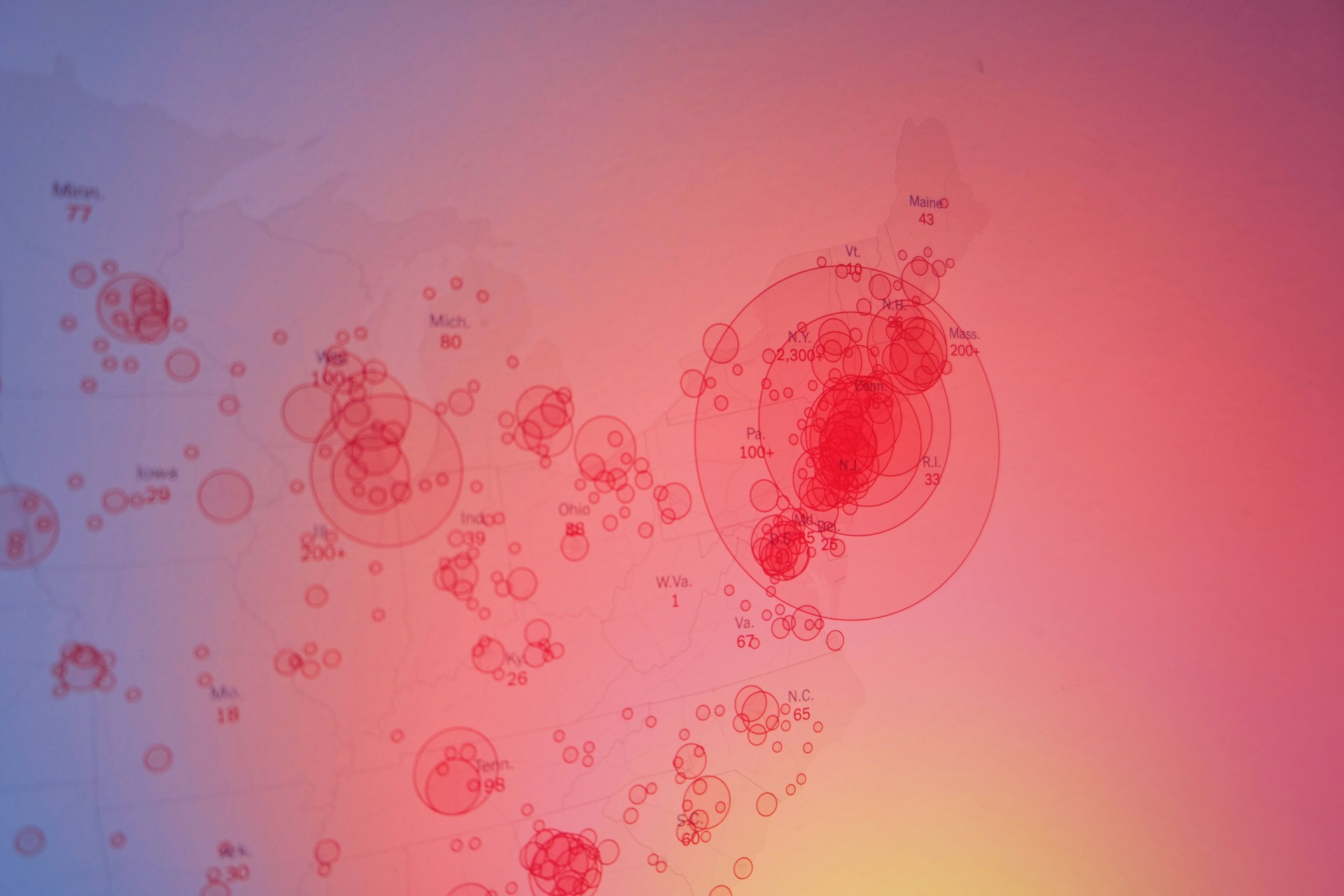

The problem with excessive efficiency, though, is that it leaves you vulnerable to negative black swans – highly improbable consequential events. These events sweep in like hurricanes, so devastating because they’re so unexpected, upending the plans of men, upsetting our careful calculations, wiping away everything we saved through meticulous improvements in efficiency. America’s healthcare system has been overwhelmed, and, as of now, COVID-19 has infected 26,959 people there and killed 349 (these numbers will be much higher by the time you read this). The economic fallout is likely severe enough to plunge the country into a recession. Naturally, in times like these, the most distraught businesses are the most leveraged ones, whilst the businesses (and countries) in best shape are the ones with the most reserves.

Just as excessive efficiency leaves you vulnerable to negative black swans, it also prevents you from taking advantage of positive black swans, the kind that come from creative breakthroughs. If we take the Oxford English Dictionary definition of “efficiency” as “achieving maximum productivity with minimum wasted effort or expense,” then research and development, which requires throwing resources into something with only a small probability of a return, instead of investing them in something with a guaranteed return, is highly inefficient. “[I]nstead of striving for lower costs and efficiency, innovative companies must opt for adaptiveness,” wrote Barry M. Staw, former Lorraine Tyson Mitchell Chair in Leadership and Communication and Professor of Management at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, in “Why no one really wants creativity.” “They need to have excess capacity and personnel devoted to seemingly meaningless ventures.”

Just as excessive efficiency leaves you vulnerable to negative black swans, it also prevents you from taking advantage of positive black swans.

Small wonder, then, that few people choose to do this, and most prefer to leave the risk (and the potential rewards) to others. “[T]o be truly innovative, firms must be industry leaders rather than followers,” Staw wrote. “They must stick their necks out on untried products and technologies, not knowing if they will be successes or failures.” The national equivalents would be Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt respectively investing in Alan Turing’s proto-computer that broke the German Enigma machine and the Manhattan Project that produced the atomic bomb, even amidst the urgency of WWII. Both these things were considered long shots at the time, but the fruit they bore fundamentally changed the rules of the game and altered the balance of power.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who coined the term “black swan,” counsels guarding against negative black swans and putting yourself in a position to take advantage of positive black swans. It’s sound advice. No one knows how long the COVID-19 pandemic will last, but when it passes hopefully we’ll be a little more careful, a little more aware of the power of chaos and randomness. Maybe some of us will be a little less efficient – and that’s a good thing.

Related posts:

Modi and His Supporters Face a COVID Reckoning

Tablighi Superspreaders in Pakistan

The Culture Factor in COVID-19

The Moral Foundations of Anti-Lockdown Anger

Are Anti-Lockdown Protests Legal?

Allegory in the Time of Coronavirus

Your Odds of Dying From COVID-19 Depend on How Polluted Your Air Is

Japanese Culture Isn’t Designed to Handle a Pandemic

The Coronavirus and the Crisis of Responsibility

FAKE NEWS | Nothing to Worry About, Says Wuhan Official From Inside Biohazard Suit

To See How Coronavirus Outbreak Might Play Out, Look at This Virtual Plague