Is It All Fun and Games?

By Felix Behr

Staff Writer

2/5/2019

Screenshot from Standoff

Impossibly large bullet casings fly off to the side of the screen as a small crowd of bizarrely identical women collapses before the fire of a rudimentarily rendered SMG. Their falls, the gun, and the corridor you’re standing in are unconvincing gestures to reality. The bottom of the screen exclaims in red caps “SHOTS FIRED. POLICE & SWAT INCOMING!” Included in the “GAME STATS” on the side are your kills: eleven civilians and five police officers.

This is a screenshot from Standoff. It’s a game like many other shooters except that it’s a lot cruder in both design and subject matter. Standoff’s title is actually a rebranding. It was originally released in mid-2018 as Active Shooter, but a petition with 200,000 signatures protesting it prompted Steam, the platform on which it was distributed, to take it down. You see, the game’s premise revolved around the dynamic of a school shooting in which you can play as the responding SWAT officer, a civilian called “Survivalist,” or the shooter.

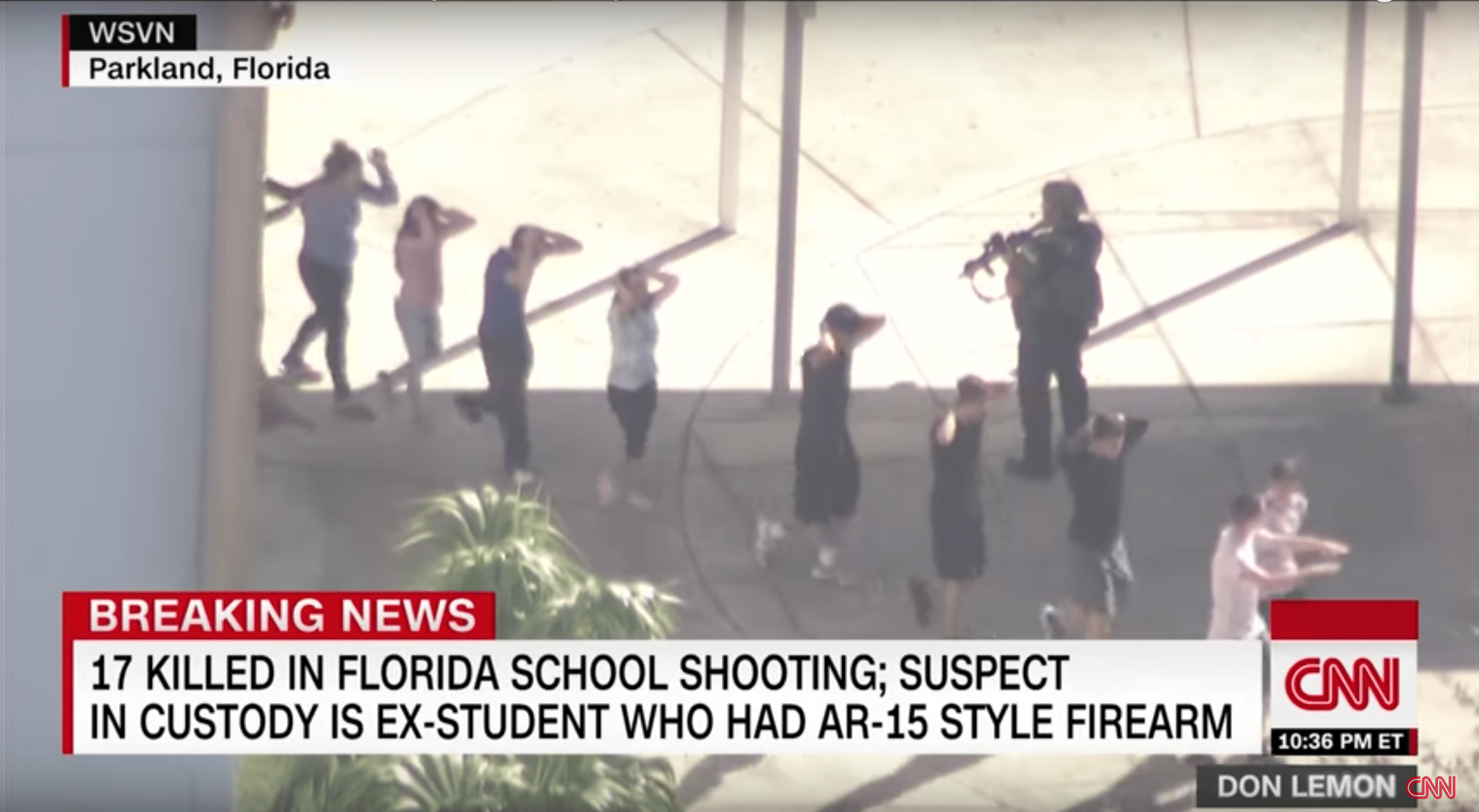

Now, selling this in the United States was, to put it mildly, tactless and tasteless. 2018 saw a record number of 97 gun-related incidents consisting of both shootings and brandishings at American schools. For reference, CNN conducted its own comparison between the US and the other six countries of the G7, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Italy, and the UK. Between 2009 and mid-2018, when Active Shooter was supposed to be released, 288 school shootings occurred in the US while the others saw a combined total of five. 2018 was also the year in which the shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida reenergized the debate over gun control, dominating that year’s media landscape. It’s almost as if the people behind Active Shooter were responding to current events in a disgustingly crude manner.

In case it wasn’t obvious, they’re trolls. Revived Games, the Russian developers behind Active Shooter, doubled down, continued working on it, and re-released it as Standoff in the same year with their own publishing outfit, Acid Software. While the game’s developer, Anton Makarevski, argued he wasn’t a “‘psychopath,’ but merely an amateur developer from Moscow with poor English skills and little knowledge of US current events,” their other titles bear similarly trolling titles like White Power: Pure Voltage, which references white supremacist groups, and Tyde Pod Challenge, an internet challenge to bite into containers of laundry detergent, both of which are also poorly programmed. If any tattered pretence of honest engagement still remained, the studio tore it away by tweeting that they’ve turned a school shooting into a game. They’re trolls to the core.

Standoff gameplay

We’re not here to feed trolls. Rather, we’re here because trolls do sometimes point to something interesting, even if they rarely intend to. So while neither Active Shooter nor Standoff themselves deserve much comment, the condemnation they received reveals a previously unexamined raw nerve. After all, as horrific as school shootings undoubtedly are, they’re not the only gun-related violent events that video games redeploy as fun. In an article titled “I kill for fun all the time. So why does Active Shooter upset me?” Stephen Bush, the political editor at the New Statesman and not a troll, wrote:

“Yes, there are school shootings in the news. But there is also any number of bloody armed conflicts going on across the world and that doesn’t seem to stop the endless procession of Call of Duty-alike games in which you can shoot your way through Nonspecifistan. Right now, gangland killings of the kind I perform for fun in Grand Theft Auto are taking place in the real world, with real casualties. Yet these two franchises are among the most successful video game properties in the world.”

Call of Duty mission

Sadly this serves more as a climax than as a rising action. After building up to this point, Bush falls back into a concluding paragraph of unanswered questions and unexplored theories, each more worrisome than the last. He asks himself if it is due to the difference in quality between Active Shooter and Grand Theft Auto, the fact that the deaths of people in America matter more to many of us than the deaths of people in Syria, or the degree to which he had already dehumanised those depicted in each game, leaving open the unsettling possibility that it’s ok to shoot the people in Call of Duty or Grand Theft Auto as society doesn’t consider them to be real people anyway. He ends on that disturbing note.

We can dispense with the first possibility. Yes, Standoff looks like it was made with the gaming equivalent of duct-taped cardboard. It’s an independent game, though. No one will begrudge it too much for either its lack of polish or anything worth polishing.

It is, of course, the subject matter. However, the response to Standoff does not reveal our individual attitudes toward war, gang violence, and school shootings as Stephen Bush worries. Rather, it shows the different places these things occupy within our technoculture, and the fears that run through it.

If the difference in response is due to the subject matter, we should then consider how a school shooting differs from the battlefield or a violent urban environment. Schools are not supposed to be violent in the same way that the other two are. A typical American schoolchild shouldn’t expect the same dangers in the classroom as they might from a traditionally dangerous environment. Now, though, they do. Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan American fact tank, conducted a survey in the wake of the shooting in Parkland, Florida and found that 57% of teenagers were actively worried about the possibility of a shooting happening at their school. Each incident is itself a tragedy, but the widespread, explicit fear that a shooting could happen is also viewed as a tragedy itself. The sheer number of school shootings combined with the heightened media coverage has brought the trauma of the daily threat of violence to everyone. Creating Standoff is like asking a Syrian to play a game in which they controlled a character ducking in and out of badly rendered replicas of Damascus. Except that it’s worse because there is also the option to give the Syrian control over the missiles that blew up their home.

Creating Standoff is like asking a Syrian to play a game in which they controlled a character ducking in and out of badly rendered replicas of Damascus.

This returns us to the hypocrisy that Stephen Bush’s final worry points towards: we’re fine with shooting anyone as long as they don’t resemble us. But Bush makes this into an issue about individual guilt. I am or we are fine with it. But by excusing the individual there is the risk of letting the cultural logic that informs the individual’s rationale off the hook.

Games like Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto don’t just reflect our culture, though, they also shape it. In his book Ludopolitics, Liam Mitchell, an Associate Professor of Cultural Studies at Trent University, notes how the popular strategy game Civilization is political because it “institute[s] a way of thinking and acting in [its] design.” In Civilization, the player rules over a civilization, beginning with a single settler and expanding it into an empire. Civilization exemplifies the 4X genre – games where the overriding objective is to explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate. Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto insert the player into a framework of rules that automatically dehumanises everyone in sight. A human is not a human but a target. The difference between this and films that glorify violence is that here the player is actively acting out the logic of certain power relations. The game may present an environment, but the player fulfills that environment’s logic. While not necessarily evil if one can dissociate between the two, the problem is the ways that these games inevitably and mindlessly play out the cruel power dynamics that usually occur elsewhere.

School shootings do not run according to the program though. Like other acts of violence, they are traumatic and disrupt the way that society is supposed to function. Unlike the other acts of violence, the market has not produced a way to package and repurpose the horror. Companies have commercialized the violence of gangs and battlefields by relying on the impersonal logic of a game. When faced with the personal, random violence of a school shooting, our logic can’t cope. It shatters the illusion that society can keep this violence under control.

I reached out to Liam Mitchell, asking him if a game could convincingly critique the distinction between “permissible” and “impermissible” violence in video games. Perhaps, he conceded, but it was more important to consider the sorts of violence a game is best capable of identifying. While a game can draw attention to many kinds of violence — Civilization is very colonial — games are best suited to depicting systemic violence. They show how a system works by showing how that system works.

For example, there’s Papers, Please, a critically acclaimed game released in 2013 in which you play an immigration inspector at the border of a recently conquered town. The mechanics of the game consist entirely of checking passports and deciding who can go through. This simplistic set up allows the game to deal with the violence of the border.

“[Papers, Please] puts the player in the position of being compelled to enact [the violent policies of border control],” said Mitchell, “since these forms of violence operate according to both the logic of the computer and the logic of the petty sovereign: the passport is legitimate or not; the border officer is following the rules or not; the officer’s family has enough food or does not. Playing that game is instructively stressful, not least because it subtly suggests that the violence that it presents – violence taking place in a time before and in a country apart – [isn’t] so removed from the here and now. The border’s logic of inclusion/exclusion is inherently violent. The creation, maintenance, and tolerance of literal concentration camps in first world countries today is exemplary, not exceptional.”

It’s a critique somewhat similar to Hannah Arendt’s description of Adolf Eichmann in Eichmann in Jerusalem. Eichmann was a logistics officer in Nazi Germany who oversaw the transportation of Jews to concentration camps. Some years after the war, he was captured and brought to Israel so that the Jews could have a cathartic trial. Eichmann, however, proved to be a poor villain as he insisted that he neither hated the Jews nor felt guilty but was just doing his job. Arendt described this phenomenon as “the banality of evil.”

Eichmann in Jerusalem

Papers, Please places the player in a similar position to Eichmann. You can’t take down the state. You can’t change the law. You’re just trying to get by. But getting by involves facing the pain that the bureaucracy inflicts on people, including yourself.

Papers, Please

The depiction of systemic violence as something that affects everyone does not trivialize the issue. Rather, it presents the questions of immigration in a totalizing, visceral way. Active Shooter does not do this. The shooting is a game and nothing more. There is nothing about any of the modes that pushes back at the player. There’s no equivalent to having to feed your family or any suggestion that these crude models have any humanity. It doesn’t present you with the choices of a system, like not shooting everyone. Rather Active Shooter presents you with a series of targets, trivializing the crisis into a game of cops and robbers.

The same critique can be thrown at Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty. Many people are appalled by Active Shooter but not by those games because they are lucky enough to be far removed from wars and gang violence. The violence of Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto is always under control for them. They reflect and shape a culture in which people can pretend that violence is kept in check by newer technologies, such as drone strikes or racially biased police software.

If you must play something that does tastefully embody a critique of real-world violence, play Papers, Please instead.