Kitsune: The Japanese Fox Trickster

By B. Alexandra Szerlip

Contributor

1/6/2019

Painting by Kawanabe Kyosai

Without deception – without the imposing of meaning on the fundamentally senseless, of pattern onto chaos – life would be, writes novelist Michael Chabon, “a terrible, useless procedure bracketed by orgasm and putrefaction. Small wonder that we should have come to revere the One who perpetrates that lie…and in so doing, lends [life] the appearance of necessity. His name is Trickster.”

Those revered deceptions – myths, legends, folk and fairytales, even religious dogma – what Chabon calls lies, “are all we have” to help us navigate our way through the world.

The trickster serves as both guide and unreliable narrator on the journey, his shenanigans transcending both time and space. He appears, in one form or another, in much of world literature, from India (Krishna), Alaska (Raven), Greece (Hermes), Scandinavia (Loki), West Africa (Eshu/Yoruba), France (Reynard), to North America (Coyote). In the Orient, he’s an almost ubiquitous presence.

***

In Japan, trickster tales can be traced back to at least the 9th century. Leaving aside kappa — mischievous spirits fond of inhabiting toilets, looking up women’s kimonos, and sometimes stealing souls by climbing inside a person’s anus — Japanese tricksters traditionally manifest as kitsune, in the guise of foxes.

The Magic Fox of Three Countries by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (Picture Credit: The British Museum)

“Shifty” is the word that comes to mind. Kitsune are adept at shape-shifting from male to female, from animal to human, and back again. The kitsune is a prankster, a disrupter, a trouble-maker, a master of illusion, a challenger of accepted notions, a wild card. On occasion she provides comic interludes, breaking up the seriousness of Noh plays, which tend to resonate with karmic retribution.

Kitsune are alternately cunning and playful, mysterious and malevolent, untrustworthy and loyal – supernatural beings that, not unlike the gods of ancient Greece, are capable of mating with humans and producing offspring. Even the word “kitsune” eludes a definitive etymology. Some scholars say it means “come and sleep” or “come always.” Others, “always yellow” or “dog smell.” It’s even been suggested that the name derives from the sound of a fox’s yelp.

Kitsune are capable of mating with humans and producing offspring.

Kitsune are capable of changing not only themselves but the appearance of other animals, humans, even buildings and towns. They fool and misdirect, creating opportunistic “accidents,” capitalizing on what some call “chance,” others “fate.” They can cause illness in both humans and livestock, put hexes on crops.

The kitsune’s targets, usually men, run the gamut from overly proud samurai, greedy merchants, and boastful commoners to poor tradesmen and guileless farmers, some of whom prove clever enough to turn their tormentor’s antics against her.

***

Shapeshifting is a primary kitsune skill. Typically, a young man (whether commoner or king) unknowingly marries a fox wife (kitsune nyobo) that has taken on a human guise. When the husband eventually – inevitably – discovers his partner’s true nature, the kitsune – who may, in fact, have proven to be a devoted spouse, and whose half-human children inherit supernatural qualities – is forced to leave her family behind.

Clever as they are, trickster foxes posing as humans are always “found out” — thanks to a fox-shaped shadow, a fox reflection in a mirror or pond, a concealed tail that appears from beneath a kimono in a moment of carelessness (or drunkenness), or thanks to kitsunes’ overwhelming fear of dogs.

The kitsune Kuzunoha by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Some rejected fox wives die of broken hearts, sacrifice themselves to protect their human families, or secretly help guide the fortunes of their descendants. (Protective fox spirits are called “kitsunetsuki.”) Still others go on to wreak havoc elsewhere. Some duped husbands (and the wailing children typically left behind) end up begging their kitsune mates to return, if only for clandestine, nocturnal visits (ergo “come and sleep” and “come always.”)

In some cases, a husband is seduced by a kitsune into abandoning his wife and children to start a second family, only to wake, as if from a dream, emaciated, filthy, disoriented, and far from home. He must then return to face his abandoned family in shame. Kitsune have the ability to bend time and space. What had seemed many years enjoying a new, fulfilling life in opulent surroundings turns out to have been merely days or weeks living in squalor – a kitsune alternate reality. Even the duped husband’s newborn son turns out to be an illusion.

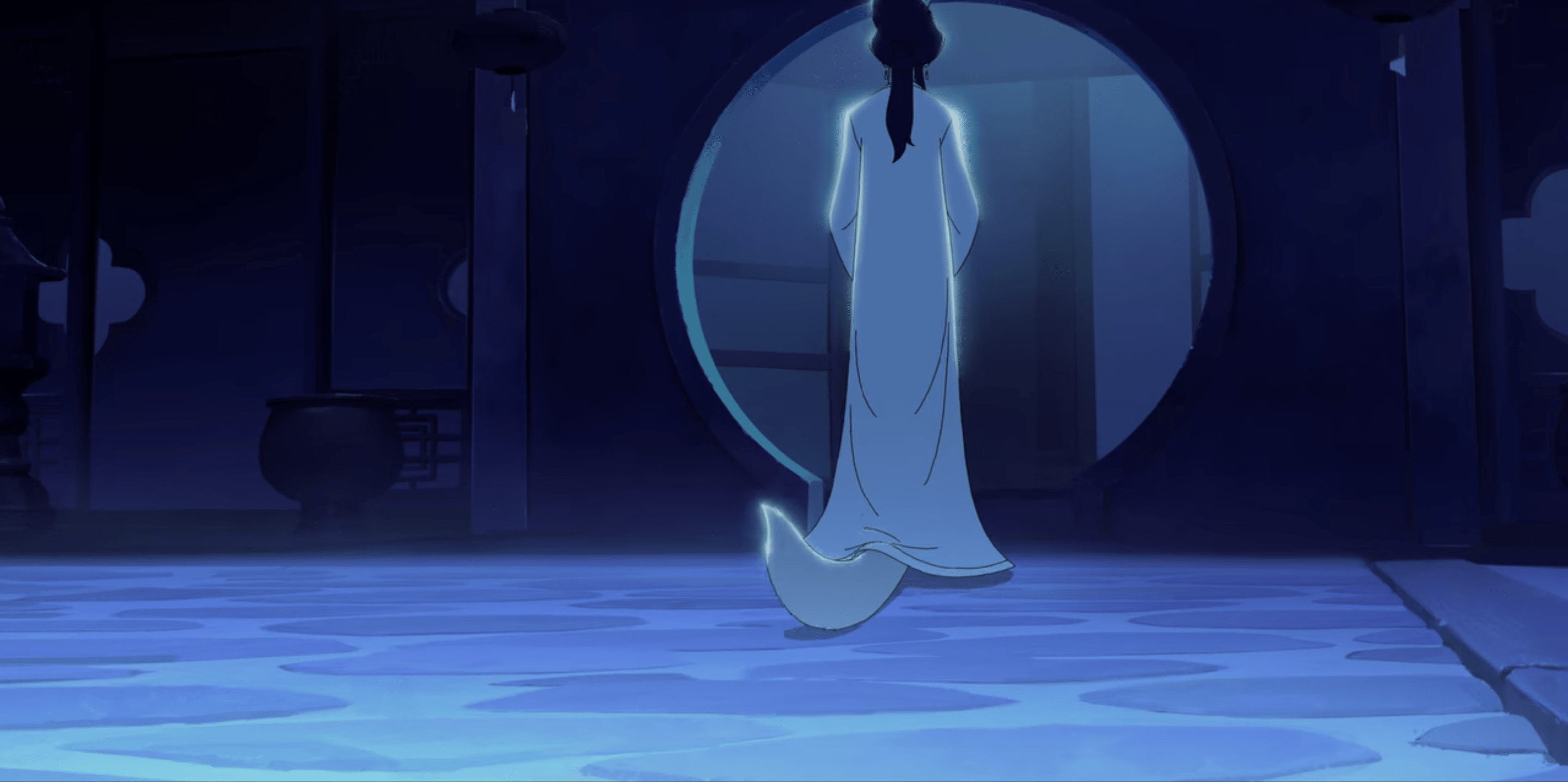

In The Sorcerer and the White Snake, huli jing, the Chinese version of kitsune, are portrayed as seductive demons capable of bending space

***

One of the oldest and most popular kitsune stories is the saga of Lady Tamamo, a.k.a. “The Jewel Maiden,” which was set in the 12th century, a period of great civic and political discord in Japanese history.

A mysterious (and flawlessly beautiful) woman of uncertain pedigree manages to infiltrate her way into the imperial court and the heart of Emperor Toba. One autumn night during a raging storm in which all the lamps are blown out, Lady Tamamo begins to radiate light like a shining star. The emperor soon sickens and grows gravely ill, breeding suspicion among the courtiers that a malevolent spirit, bent on nothing less than the destruction of the dynasty, lurks amongst them. All fingers point to the emperor’s mysterious favorite, but Toba refuses to suspect her. A purification ceremony, staged by a local exorcist, eventually forces Tamamo to reveal her true form – a nine-tailed fox – that quickly flees to the northeast, the traditional go-to destination for Japanese demons.

(As for the nine tails: It’s generally understood that the more tails a kitsune has, the more powerful it is, to the point of being able to see and hear things happening anywhere in the world. Some tales suggest that it takes 1,000 years to acquire the ultimate nine, at which point a kitsune becomes a tenko or heavenly fox, recognizable by its golden fur.)

The Magic Fox of Three Countries by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (Picture Credit: The British Museum)

The Jewel Maiden doesn’t escape. The fleeing fox is subsequently pursued by bow-toting warriors on horseback and eventually killed with help from a bodhisattva. The vengeful, now-bodiless, spirit then takes up residence in a “murder stone” that emits noxious gases.

In the centuries following its creation, Lady Tamamo’s story went on to inform everything from poetry and illustrated scrolls to puppet plays and Noh dramas. Seduction, deception, jealous rivals, exorcists, valiant warriors. How could “The Jewel Maiden” not have enduring, and widespread, appeal? In China, Tamamo’s fingerprint can be found in the story of King Yu (whose wife, Queen Dakki, is “inhabited” by an evil spirit bent on destruction); in India, a nine-tailed fox spirit (Kayō-fujin) inhabits Queen Kayou, wife of King Hanzoku, convincing him to behead a thousand of his own countrymen.

***

Kitsunetsuki literally means ”the state of being possessed by a fox.” The victim, usually a young woman, can be “entered” any number of ways, including beneath her fingernails or through her breasts. Folklorist Lafcadio Hearn wrote that fox possession can cause illiterate victims to gain the ability to read and that once freed, they’re never again able to eat tofu, a favorite fox food.

It was a popular belief in medieval Japan that any woman encountered alone, at dusk or after dark, could be a fox. In some cases of possession, the victims’ facial expressions were said to change in such a way that they resembled those of a fox. Traditionally, the Japanese consider a narrow face, close-set eyes, thin eyebrows, and high cheekbones – fox-like features – desirable female attributes. Being desirable is a power unto itself and so, perhaps, also “dangerous.” In the West, interestingly, sexually attractive young women are often referred to as “foxy.”

Kitsune-gao (a fox-face)

The ubiquity of kitsune nyobo – they rarely, if ever, transform into fox husbands – suggests everything from the complex nature of marriage (its constraints and uncertainties) to a perception of women as outsiders or dangerously seductive vixens, ”wild” elements introduced into the domestic sphere that must be controlled. Some scholars have suggested that fox wife stories address the idea of marrying outside one’s clan, or “marrying for love.” Put another way, they explore the pros and cons of short-term (selfish, short-sighted) passion versus long-term pragmatism, the price of breaking with tradition.

Many of the earliest tales were collected, and possibly augmented, by Buddhist monks who had, as one scholar puts it, “a characteristically negative outlook on family life.” (In at least one version, it’s the Buddhist monk himself who succumbs to sexual temptation.) Some decidedly sinister fox wives are portrayed as vampires, drawing energy from others to augment their own.

Some decidedly sinister fox wives are portrayed as vampires, drawing energy from others to augment their own.

Some versions can also be read as reflecting marital traditions. A Japanese wife in medieval times was expected to leave behind all ties to her birth family in exchange for unquestioning loyalty to her husband’s kin. So too with the kitsune, who had to surrender (or at least hide) her animalistic and spiritual heritage when she wed a human. When her true nature is discovered (as it always is), her child (always young, always a son) then faces his own choice: between allegiance to a human father or a vulpine mother.

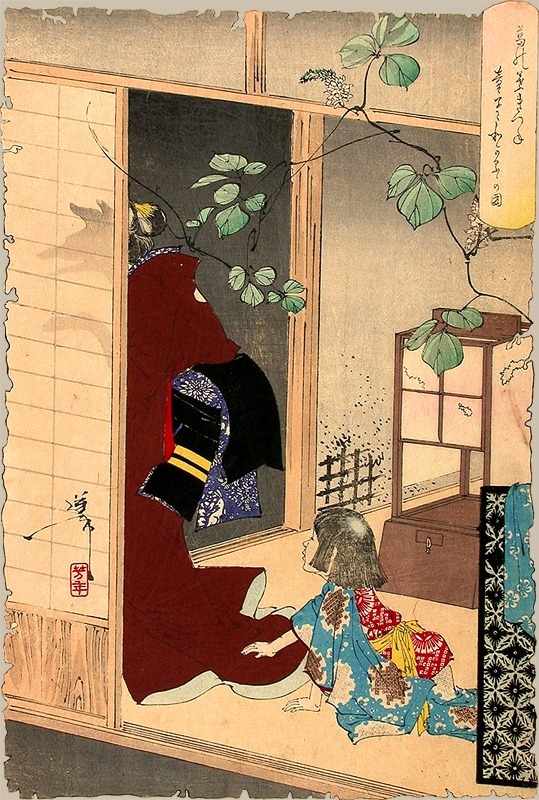

The Fox-woman Kuzunoha Leaving Her Child by Yoshitoshi

More than merely fantasy, these stories reflect enduring human issues about lineage, patrimony, loyalty, domesticity, and the push-pull between one’s animal nature and society’s expectations.

***

Another kind of kitsune story presents the fox as a bringer of wealth and good fortune – at least for a while. These particular tales emerged from the Edo period (1603-1867), a time when, after more than a century of civil war, a nouveau riche class emerged that viewed the accumulation of money as the be-all end-all. A proliferation of shrines to Inari, goddess of foxes, but also of agriculture (specifically rice), and by extension of worldly success, reflected the change. But the rash of new consumer goods coexisted with failing crop prices; many peasants were forced into debt or lost their land.

Fox statue at Fushimi Inari shrine in Kyoto

In “The Lucky Teakettle,” a kitsune assumes the form of various saleable objects as repayment to a man who saved its life. With each sale, the man’s fortune grows. But when the fox turns into a teakettle, the buyer puts it on a hot stove and the fox is badly burned. When she turns into a handsome horse, she’s unable to bear the weight of the feudal lord who buys and mounts it; the fox gets dumped, exhausted, in a muddy ditch. At a time when the accumulation of currency for its own sake was considered “more valuable” than the availability of staples (like rice or tobacco), wealth is depicted with ambivalence: happiness for some, misery for others. A “lesson” at least as relevant today as it was 400 years ago.

The increasing schism between haves and have-nots, ironically brought on by prosperity, was viewed by many as, at best, corrosive, at worst, a cruel deception. What then, the story asks, is the true measure of value? Boundaries transgressed, traditions destabilized – this is the kitsune’s landscape, its raison d’etre.

A huli jing, the Chinese version of kitsune

***

Despite our best efforts to “package” myths or reduce them to the status of children’s fare, they will always be with us, as long as life’s uncertainties exist. The trickster tradition, in particular, will remain rich and robust.

Today, in the 21st century, kitsune informs the lyrics of Babymetal, the all-girl Japanese heavy metal band, which includes fox masks and fox animations in their performances. Kitsune – in the form of characters like Hans, Redd, Ahri, Ninetales, Xiaomu, Yuzuhura, Okami, Carmelita Montoya Fox, and Fox McCloud – hold pride of place in a range of video games. Playstation’s Spirit of the North follows the adventures of an ordinary red fox whose life becomes entwined with a female fox spirit whose realm is the Northern Lights. The fox spirit, known in Chinese as huli jing, made a recent appearance in Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots series.

A huli jing in Love, Death & Robots

Feeling lost is intrinsic to the human condition. We want – we have always wanted – to believe that our wanderings have purpose and meaning, that life is more than, as Chabon put it, merely useless and terrible, that obstacles can, and will, be overcome, deceptions unmasked, duplicities exposed, transitions weathered with grace. Tricksters – be they Coyote or Raven, Loki or Hermes, Reynard or kitsune – provide an explanation for the seeming randomness and inequalities of the world. The chaos they perpetuate, by their very nature, helps us make sense of, and find solace in, that world.

We are, after all, the ones who invented them in the first place.