Laugh in Translation

By Richard Milner

Staff Writer

2/1/2020

Picture Credit: John Carkeet

Turn on a tv in Japan and you’re likely to come across a “variety show.” They’re a dime a dozen, and are largely considered the trashiest of Japanese trash tv. They feature panels of minor celebrities, comedians, and guests chatting about random topics, cracking jokes, and commenting from a tiny screen in the bottom corner as they (and viewers) watch videos of food, animals, or man-on-the-street interviews. Segments are cut with jarringly quick on-screen text overlaid by spastic narration and interspersed with seemingly random comedic bits (that often include more food or animals). Production quality is often low enough to look like a homemade sitcom shot in someone’s backyard with a phone.

Watching a variety show is like watching a separate, bubble universe that obeys no external logic, and instead conforms to nothing but rules of warped acceleration and mercurial timing. It’s a mind-numbing slap in the face that may look absolutely bizarre to someone from another country.

Watching a variety show is like watching a separate, bubble universe that obeys no external logic.

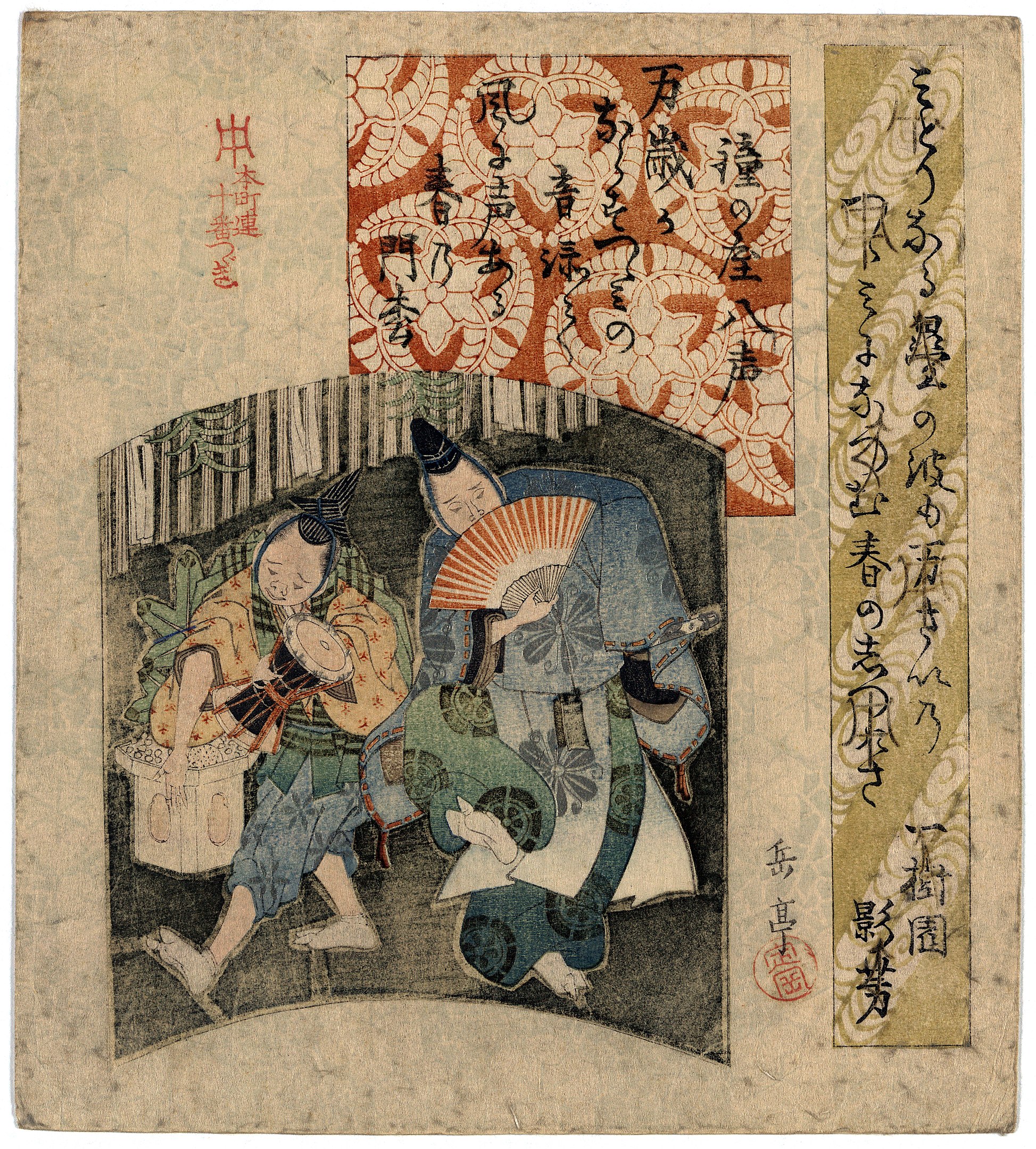

This type of show typifies the kind of wacky, surreal comedy that has come to perhaps rightfully characterize Japanese humor to the outside world. But contrary to initial impressions, such “low comedy” is not at all arbitrary in form; it’s in fact part of a very particular suite of formalized Japanese comedic traditions that include manzai (comedy duos focused on banter and wordplay) and rakugo (stand-up comedy, except sit-down, and wearing traditional clothing) that have wound their way through time to form the bedrock of modern Japanese comedic sensibilities. These sensibilities, in turn, reveal a lot about the character of Japan as a nation.

Rakugo

One of the most popular television comedians of the past decade, Yoshio Kojima, made his entire career out of the single gag of prancing on stage wearing nothing but a diaper, making absurd faces and saying catch phrases with music in the background, and then doing a signature arm pumping dance that always sent the audience into wild, uproarious laughter.

Kojima and comedians like him are genin, which loosely translates as “low person,” but in essence is closer to “clown,” “fool,” or even “jester.” A Japanese literature graduate of Waseda University, one of Japan’s top-ranked private universities, Kojima was clearly playing a role when he donned his diapered character, much like a professional cosplayer.

Genin and other actors during the Edo period (1603-1868) were considered part of an untouchable, low socioeconomic class that contained outcasts, misfits, and people in “dirty” occupations like butchers or tanners. The vocation itself, though, was recognized as a suitable profession for the artistically or creatively inclined (entire theaters cropped up for rakugo as early as 1781). Samurai specialized in fighting, farmers specialized in agriculture, merchants specialized in trade, and genin specialized in being weird. Gatekeepers across Edo (the old name for Tokyo) often allowed genin free access across districts without passports in exchange for some kind of funny trick or comedic routine. Imagine a poor, medieval, Japanese clown juggling rocks to gain passage through a city gate and you might have an idea of what presaged the modern role of genin as tricksters or purveyors of amusement.

The overblown, hyperbolic tenor of Japanese comedy can be traced back to this era, and arguably originates in kabuki, a form of Japanese theater that also began in the Edo era, where actors wear masks, dance, and act out a series of storytelling through dialogue and pantomime. In kabuki, actors embellish their movements, speak in an exaggerated manner, and over-enunciate vowel sounds so that dialogue can carry through an entire theater. In short, they are very obviously acting. And because kabuki is, at present, the most revered form of acting in Japan, comedic acting has followed suit as an offshoot of the larger cadre of Japanese theater arts. In short: in modern Japan overacting is good acting.

Manzai duo

In Japan comedy has never been, and is never, used for political satire or to touch on serious topics circulating through public discourse (racism, sexism, religion, economics, war, etc). In Japan funny is funny because of the lighthearted emotion attached to it. Funny is what doesn’t matter.

For this reason, Western satire and irony often goes over the heads of a Japanese audience. Sit in an audience in a Japanese theater watching a movie from the US or UK and you’re likely to hear dead silence at any comedic bit (except for scattered chuckles from the few Westerners in the crowd). Sure, there may be translation issues at hand, or highly contextualized jokes that require knowledge of pop culture references, but even accounting for that, most of the humor still falls flat.

In the West, comedy is also used to broach subjects that can’t otherwise be discussed easily, like death or rape. The concept of “black humor” exists in Japan, but is somewhat taboo, and in general serious topics ought to be approached seriously; any other tact is considered irresponsible and insensitive. Heavy topics also run the risk of leading people to commit the nation’s cardinal sin: making others uncomfortable (this kind of discomfort is different from the cringe inherent to comedy). Subject matter that isn’t commonly agreed upon, and could potentially lead to differences of opinion, is simply not talked about.

Heavy topics also run the risk of leading people to commit the nation’s cardinal sin: making others uncomfortable.

And so, on the surface, humor takes the form of the inoffensive or the absurd. See someone aimlessly picking through a pile of leaves on the ground? Funny. Making absurd appreciative noises while eating delicious street food? Funny. An adult in a diaper mindlessly prancing around on stage? Funny. These comedic situations are not just simple observations or subversions of expectations, though; they portray either non-conformity to behavioral norms or an inability to regulate one’s own behavior. In a society so focused on public scrutiny, any such action is embarrassing to either witness or experience. Seeing it out in the open is what produces the comedic reaction.

Schadenfreude (pleasure at someone else’s misfortune) and its mirror fremdschämen (embarrassment at someone else’s misfortune) are very much alive in Japan, then, to the point of having Japanese-language equivalents: hito no fuko wa mitsu no agi (another’s misfortune tastes like honey) and kyokan-shuchi (sympathy-embarrassment). Comedy is simply the safe place where these sentiments can be exposed and expressed, no matter how they might otherwise disrupt the overall sense of Japanese public decorum. Comedians are, effectively, exposing themselves to ridicule on behalf of the greater good as a psychological salve: it’s acceptable to derive mirth from mocking them, and you don’t need to feel bad for them because they’re supposed to do stupid things. They are shame surrogates.

Comedy is the safe place where these sentiments can be exposed and expressed, no matter how they might otherwise disrupt the overall sense of Japanese public decorum.

Foolishness itself is not the point of Japanese comedy, then, nor is Japanese humor derived from a keen sense of existential absurdity. At minimum, it is a happy distraction, a wacky trick of misdirection at a samurai-guarded gate. At most, as an outlet for everyday worry about breaking social protocol, a coping mechanism that reveals much about societal fears and hang-ups.

Despite Japanese comedy’s veneer of fluff and nonsense, it reflects certain aspects of the Japanese character – avoidant, non-self-analytical, and prone to psychological compartmentalization. This, combined with traditional comedic forms (genin, manzai, rakugo), and a characteristically over-the-top delivery, makes Japanese comedy truly unique.

Related posts: