Malaysia’s King Should Explain His Decision

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

8/3/2020

The National Palace, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Last Saturday, Malaysia’s king made the controversial decision to appoint Muhyiddin Yassin prime minister. Muhyiddin got himself appointed by betraying Pakatan Harapan, the ruling coalition he was part of, and allying himself with UMNO, the kleptocratic party he denounced and helped to depose in the last election. At a stroke, this political coup disregarded the mandate given to Pakatan Harapan by voters in the 2018 election, strangled Malaysia’s fledgling democracy in its cradle, and enabled the corrupt authoritarians of UMNO, and the Islamofascists of its ally, PAS, to form a government.

None of this makes the king’s decision controversial. Like the UK, Malaysia is a constitutional monarchy where the people’s will, funneled through their representatives in parliament, is meant to be sovereign, and the powers of the monarch are strictly limited. Under Article 43(2a) of Malaysia’s Constitution, the king is obligated to appoint any member of parliament who “is likely to command the confidence of the majority of the members of the House.” That is to say, the king has to appoint whichever MP has majority support in parliament, even if he happens to be a duplicitous party-hopper allied to a gang of thieves.

Like the UK, Malaysia is a constitutional monarchy where the powers of the monarch are strictly limited.

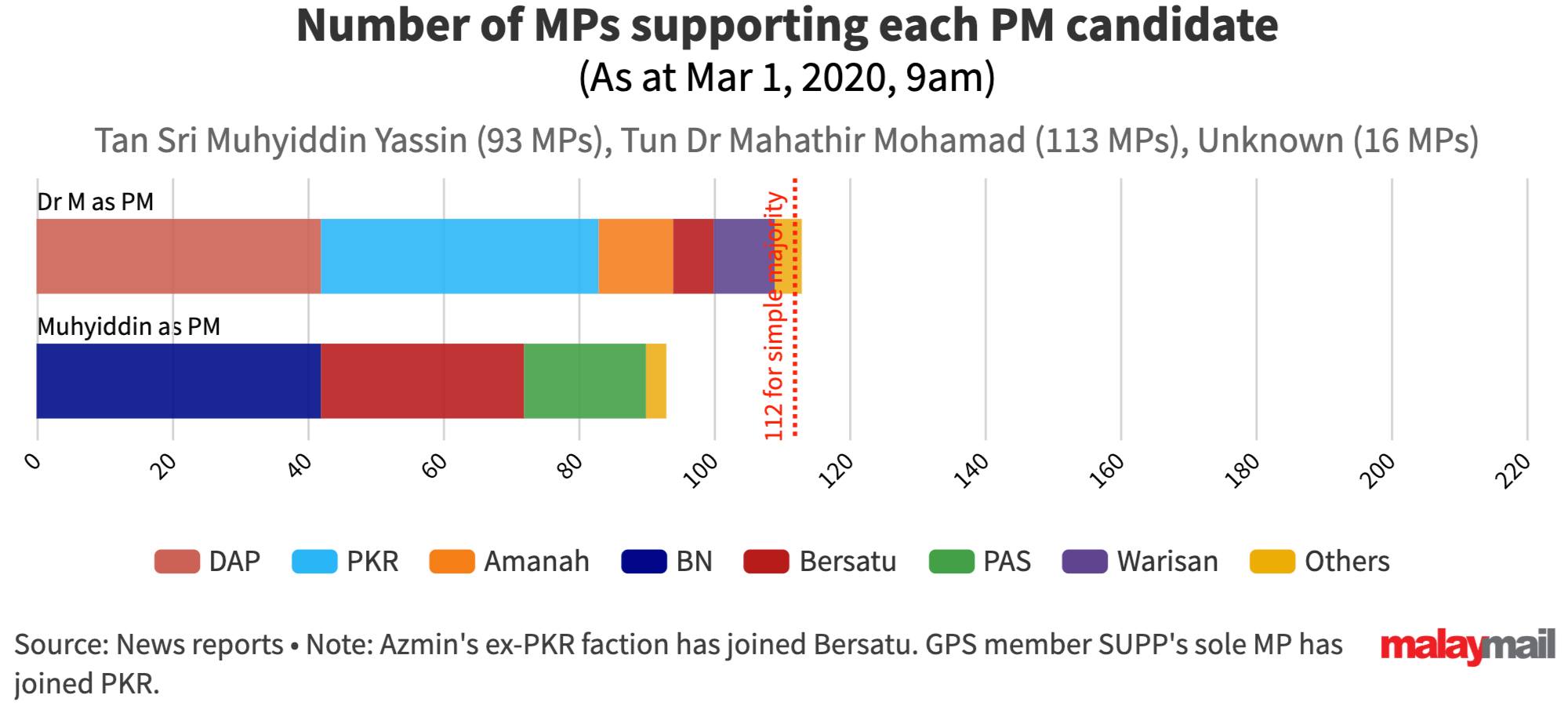

What does make his decision controversial is the fact that Muhyiddin doesn’t appear to have a parliamentary majority. Even after Muhyiddin jumped ship with his supporters, the remnants of Pakatan Harapan said last Saturday that it had managed to cobble together a majority of MPs. If this claim was true, then the king would have been obligated to appoint Pakatan Harapan’s leader, Mahathir Mohamad, prime minister instead of Muhyiddin. Yet the king refused to even meet Mahathir then so he could show him he had a majority. A few hours after the king announced his decision to appoint Muhyiddin prime minister, Pakatan Harapan put up a list of 114 MPs (just above the 112 needed for a majority in Malaysia’s 222-member parliament) it said had signed statutory declarations affirming their support for Mahathir. (That number later dropped to 113.) On the day Muhyiddin was sworn in, the Malay Mail, a local news site, published an infographic illustrating the known support of the two candidates which showed Mahathir with the support of 113 MPs and Muhyiddin with the support of just 93. The apparent result was, as Mahathir put it, that “[t]he loser would form the government, while the winner will become the opposition.” Supporters of Mahathir were shocked; supporters of Muhyiddin were surprised; almost everyone was confused.

Reproduced with permission from the Malay Mail

Events in the following days only added to this confusion. Muhyiddin and his allies have yet to put up their own list of supporters to counter Pakatan Harapan’s claims. Though parliament was supposed to convene on 9th March, Muhyiddin has postponed its sitting until 18th May. If Pakatan Harapan has a parliamentary majority, as it claims, then it can depose Muhyiddin’s government through a vote of no-confidence as soon as parliament convenes, and so the obvious implication is that Muhyiddin doesn’t actually have a majority, and is trying to buy time until he can suborn enough MPs to obtain one. Perhaps doubting his legitimacy as prime minister, other heads of state seem to be hesitating to congratulate Muhyiddin, with only the leaders of Singapore and Indonesia having done so. Of course, politicians everywhere have been known to lie and mislead, to claim they have a majority when they do not, but the fact remains: Mahathir has published a list of his supporters showing a majority and Muhyiddin has not, and Muhyiddin seems to be running from parliament whilst Mahathir is not.

Why, then, did the king choose to appoint Muhyiddin prime minister? If Mahathir really had majority support, there would have been no room for discretion. “The king has to exercise his discretion in accordance with the Constitution,” said constitutional lawyer Lim Wei Jiet. “Hence, if [he] appoint[s] someone with less than 111 MPs as prime minister, arguably that decision is unlawful and can be challenged in court.”

Some suspect bias: that it’s because the king dislikes Mahathir (as Malaysian royals in general are said to), or because he’s sympathetic to Muhyiddin’s Malay-Muslim supremacist coalition. An editorial in The Guardian described his decision as “a royal coup” that “overturned a democratic election result.” Three people in Malaysia are being investigated for insulting the king on social media (Malaysia has lèse-majesté laws) over this incident, with one of them accusing him of “undermining democracy.”

The fact is, though, that no one knows. Until Saturday, at the very least, King Abdullah has seemed like a decent man who takes his constitutional duties seriously, and there may have been perfectly legitimate reasons why he appointed Muhyiddin as prime minister, but without an explanation from the palace, a thousand suspicions fester.

King Abdullah

The king could end those suspicions by explaining his decision. Such a thing would be unusual, but these are highly unusual circumstances, something he himself seemed to acknowledge when he took the unusual (and laudable) step last week of personally interviewing all 222 MPs to try to determine who most of them supported. There’s nothing, of course, requiring him to do so, but, then again, there’s nothing preventing him from doing so either. “The king can of course do as he wants,” agreed Lim. “It is good for democracy and transparency purposes for the king to disclose the number of MPs who supported Muhyiddin as prime minister.” Whilst an explanation wouldn’t be needed in obvious cases, for example, where the king appoints the candidate with a clear majority as prime minister, it’s critical in a case like this, where he seems to have made the opposite choice. A good explanation would leave no room for misunderstanding and help restore public confidence in the system.

A good explanation would leave no room for misunderstanding and help restore public confidence in the system.

“Justice,” it’s said, “must not only be done; it must be seen to be done.” This is why judges usually give detailed explanations for their decisions in court proceedings open to the public. If such a thing is important in the day-to-day administration of justice in a court of law, then how much more important is it in a matter of national, constitutional importance, where the present government is widely viewed, both nationally and internationally, as having no legitimacy, where half the country feels like its been cheated, like their votes have been nullified, where the stakes are no less than whether the nation transitions into democracy or not? Silence may appear dignified, but it’s a text easy to misread. It’s in the nature of people to speculate in the absence of a logical explanation, and, when great power is at stake, some will suspect the worst, and will think it, even if they don’t dare to say it openly. It’s in the nature of people to question, and, if no answer is given, they’ll create their own.