Melting Palaces

By B. Alexandra Szerlip

Contributor

4/9/2019

Ice palace in Harbin, China, 2010

The winter of 1739-1740 was one of the coldest in history. The Thames, the Seine, the Rhine and the Danube rivers froze solid for months. In the Ukraine, birds fell dead from the sky while attempting to fly south. At Versailles, the Duc de Saint Simon complained that, even in rooms heated by great fireplaces, brandy bottles burst and at dinner, wine froze in the drinking glasses.

The intense cold wave extended east across the vast expanse of Russia. In Saint Petersburg, the reigning monarch — Tsarina Anna Ivanova, niece of Peter the Great — came up with a plan, a hugely expensive “bread and circuses” distraction for a suffering populace. (Along with being poor and ill-equipped for temperatures extreme even by Russian standards, the citizenry was restless in the wake of several excessively brutal political executions Ivanovna had ordered.) The royal architect, Eropkin, drew up plans for a unique Italianate villa.

Hundreds of laborers and artisans were set to work. The clearest ice from the frozen River Neva was carefully measured with compasses and rulers, sawed into blocks, and assembled with cranes. Completed, the building stood somewhere between 21 and 33 feet high (depending on which account you read), 56 to 80 feet long, and 17 to 23 feet wide. “The transparency and bluish tone of the ice,” wrote a contemporary, was “infinitely more beautiful than if it had been constructed of the finest marble.”

Imperial mistress of fur-clad Russ

Thy most magnificent and mighty freak

The wonder of the North,

wrote English poet William Cowper.

No forest fell…No quarry sent its stones…

thou didst hew the floods…

Ice upon ice, thy well-adjusted parts

Were soon conjoined…

Freezing water, used as mortar, cemented the blocks so smoothly that the structure appeared to be of a single piece.

Surrounding the fairytale-like manse was a forest of ice trees inhabited by ice birds. Six elaborate ice statues guarded the entranceway. Ice spires housed candlelit paper lanterns. Atop the gate posts were pots of fruit-bearing dwarf orange trees. The trees, like the birds, were painted in natural colors; the palace’s doors, support pillars, and window frames were hand colored to resemble green marble.

No detail was too small. Thanks to an elaborate plumbing system, a pair of ice dolphins sprayed jets of water, as did a life-sized ice elephant fountain, ridden by a carved, costumed Persian. (The elephant also roared, thanks to a real man lodged inside with a trumpet.) Half a dozen ice cannons were designed to be loaded and fired — a quarter pound of gunpowder for each shot — much to the public’s delight.

Inside the palace, all the furniture, even a clock, was frozen, glistening and transparent. In the drawing room, real playing cards and counters were frozen onto the tabletop. Cupboard shelves held meticulous replicas of various tempting dishes, colored in their natural tints, along with a tea service, ice silverware, and ice glasses.

Inside the palace, all the furniture, even a clock, was frozen, glistening and transparent.

The sleeping chamber, the piece de resistance, featured an elaborate curtained bed with a feather mattress and quilt. A nightcap rested atop each fluffed pillow. There were two pairs of slippers, a dressing table laden with boxes and candlesticks, a handsome, ornate mirror. Everything carefully fashioned from ice. A fireplace held ice logs that could be set aflame, on special occasions, with a dousing of petroleum.

But perhaps more extraordinary than Ivanovna’s palace was her plan for its unveiling.

Famous for her cruelty and perverse humor, the Tsarina was particularly fond of subjecting the old nobility, who’d opposed her ascension to the throne, to ridicule. When she discovered that one of them, the recently widowed Prince Mikhail Golitsyn, had had the temerity to re-marry — without her consent, and to a European Catholic — she had the marriage annulled and forced Golitsyn to dress up like a hen and sit, clucking for hours, on a straw basket of eggs, for the court’s amusement. Not satisfied, she found him a new bride, an ugly, middle-aged servant she nicknamed Buzhenina — after the Tsarina’s favorite dish of pork, vinegar, and onions.

The new palace would have been an ideal mise-en-scene for a Midwinter Night’s Dream ice ballet. It would serve, instead, as a honeymoon suite.

On February 17, 1740, a gaudy, extravagant parade (lewd wedding processions of dwarves, costumed musicians and exotic animals — camels, bears, reindeer, wolves — were a tradition handed down from Uncle Peter) culminated with the couple being forced to spend the night on the elaborate ice bed. It’s unknown whether they were stripped of the furs they’d worn while being carried through the streets, in a cage, as part of the parade. Guards were posted throughout the night to bar escape.

Painting by Valery Jacobi, 1878. Golitsyn and his bride sit in their frozen suite as the Tsarina (in gold) leads a band of revelers.

In one version of the story, Buzhenina subsequently bore Golstyn two sons; in another, she died of a severe chill a few days after the nuptials. Eropkin’s glory days, meanwhile, proved short. By the following summer — his creation by then melted down to mere floating blocks — the architect had been condemned as a traitor, and credit for his translucent marvel attributed to a court functionary.

Uniquely beautiful, the first documented ice palace ever built was also the shortest-lived structure in the history of architecture. Larger ones would eventually follow, but none with a more compelling story.

***

Eskimos had, of course, been building relatively simple domed ice dwellings with wind slab snow (versus elaborate vertical walls with river ice), since pre-history, some as large as 20 feet in diameter. The tensile strength of ice, it turns out, is about 300 pounds per square inch and, when rapidly loaded, in temperatures of 20ºF, it acquires an impressive, compressive strength of 1,500 pounds per square inch.

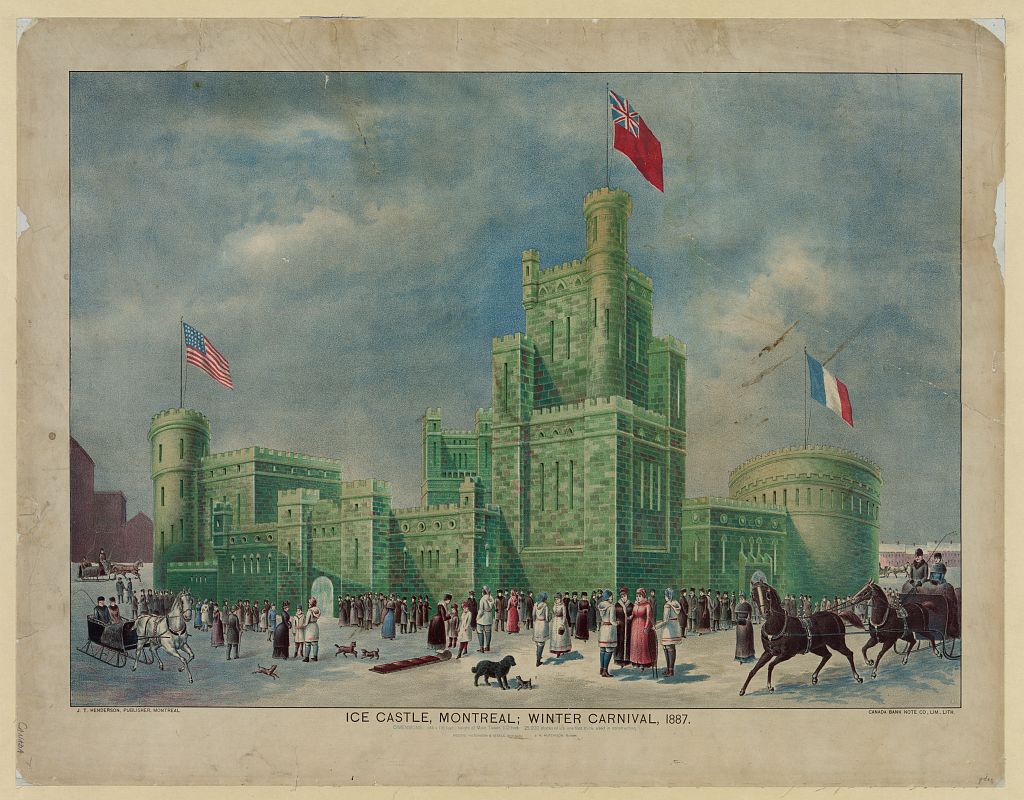

In the 19th century, ice palaces crossed the Atlantic. North America’s first was erected in 1883 in Montreal, 143 years after Anna Ivanovna’s (the same year the Brooklyn Bridge opened), designed as the centerpiece for a winter sports carnival. Ice harvesting for refrigeration was a thriving business by the late 1800s. A crew of 50 cut 500-pound blocks from, as one newspaper put it, “the bosom of the noble River St Lawrence.” Peaked roofs, formed with beams and green boughs, were covered with water, which froze into sheets of icicles. (The architect, one A. C. Hutchison, had, as a young man, been in charge of cutting the stonework for Canada’s Parliament buildings.)

The following winter, Montreal erected an even larger, more elaborate castle (some 15,000 blocks); in 1885, the tower stood 100 feet tall.

“It is wonderfully beautiful in daylight,” wrote a New York Times reporter, but after dark, “one sees to perfection…the gleaming sea-green united ice shining in the heavens above with that clear brilliancy seen only in extremely cold countries.” And with electric lights, still a novelty, shining out from its turrets and towers, it rivaled “the marvelous imaginings of some opium-sated dream…”

A 2,500-foot toboggan slide was added to the festivities, illumined at night with flaring torches, and a colossal, 20-foot-tall ice lion. Mock battles (“the storming of the palace”) fought with fireworks were introduced. (A Gatling gun that discharged colored missiles from one of the towers had somewhat disastrous results.) There were fancy dress skating balls, concerts, grand sleigh and bobsled rides.

In 1887, the city of St Paul, Minnesota cut into both the frozen Mississippi River and Lake Como (lake ice tends to be clearer than river ice) in preparation for the city’s first annual Mid-Winter Crystal Carnival, a response by city fathers to having had their city described, in a New York newspaper, as “another Siberia, unfit for human habitation in winter.”

Somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000 400-pound blocks, marked off with a horse-drawn, plow-like device, were sawed out, then transported on sleds. Because of the blocks’ large size, construction (using horse-powered pulleys and heavy ice tongs) progressed rapidly; curved outlines, like for towers, were carved with axes before being hoisted up. A block could be laid down and “cemented” in little more than a minute. Even on the coldest days, large crowds gathered to watch as the enormous structure spread out over almost an acre.

The following year’s palace required 55,000 ice blocks and stood 130 feet high.

It was three stories in the air, with battlements and embrasures and narrow icicled windows, and the innumerable electric lights inside wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald, a St Paul native, in an early short story, circa 1922. “It’s a hundred and seventy feet tall,” Harry was saying to a muffled figure beside him as they trudged toward the entrance; “covers six thousand square yards.”

She caught snatches of conversation: “One main hall” – “walls twenty to forty inches thick” – “and the ice cave has almost a mile of-” – “this Canuck who built it… “

They found their way inside…dazed by the magic of the great crystal walls…

Ice palace at St Paul, 1986

In the 1930s and early 40s, some ice palaces were decidedly Art Deco. Thousands of square feet of tinted gelatin were inserted between the walls so that after dark, lit by thousands of bulbs, whole sections would periodically shift color.

Quebec and Ottawa also took up the mantle of annual Winter Carnivals with ice palace centerpieces. But by the late 1970s, given increasing construction costs, many venues eschewed ice blocks entirely for sculpted snow.

***

Japan’s Sapporo Snow Festival, initiated in 1950 when high school students built a few snow statues in Odori Park, brought the ice palace to Asia.

Like cherry blossoms, elaborate frozen sculptures and statues, destined to survive only a short time, exemplify the very Japanese idea of mono no aware: that beauty is ephemeral, transient, fragile, impermanent. That said, Sapporo’s architectural constructions (a replica of the Japanese government’s headquarters in Hokkaido, Osaka Castle, a domed Moscow cathedral, Hawaii’s Iolani Palace, even Cinderella’s imaginary palace) were and are statues and sculptures, rather than true buildings. Though meticulously detailed, they lack interiors and cannot be entered.

So too with China’s Harbin International Ice Festival, which began as a traditional ice lantern show before expanding, in 1963, into a grander, state-subsidized, public diversion. Interrupted during Mao Zedong’s decade-long Cultural Revolution, it eventually returned as an annual event commencing each January 5th in Zhaolin Park. Among its offerings are a Snow Town (“Experience the lifestyle of local peasants”) and safari-style Siberian tiger watching. Primarily sculptures, it’s also home to full size replicas of world-famous landmarks (the Eiffel Tower chock-a-block with Rome’s Coliseum and the Tower of London) made from blocks of two-to-three-foot-thick ice taken directly from the Songhua River. After dark, their bright Technicolor lighting lends a very Las Vegas feel.

Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival, 2010 (Picture Credit: Michael Kan)

***

Today, the closest thing to traditional ice palaces — that are built, not simply sculpted, and have interior rooms — are ice hotels, a half dozen of which have opened over the past 30 years. But unlike their role models, ice hotel facades are far less interesting than their interiors. For several hundred dollars a night, anyone can channel a Golitsyn-and-Buzhenina-like experience. All feature wedding chapels; rooms are equipped with sleeping bags, insulated sheets, and the occasional reindeer pelt.

Sweden’s Jukkasjärvi Ice Hotel, 200 km north of the Arctic Circle, debuted in 1990. Open all year round, it’s kept cool during summer months by solar panels. Each year, 40 artists are invited to design and hand carve a new set of thematic “art suites” using snow and ice from the River Torne, each destined to last only a season. “The notion that several weeks’ hard work and months of planning and preparation culminate in something that only exists for a few months,” notes the hotel’s website, “is in some respects a bittersweet feeling.”

Room at Jukkasjärvi Ice Hotel (Picture Credit: Rob Alter)

Other venues include the Iglu Dorf (Igloo Village) in Gstaad, Switzerland (accessed by cable car, 2,000 meters above sea level with stunning mountain views, optional nocturnal snowshoe hike and snow sculpture lessons); the Hotel of Ice in Sibiu, Romania (their exclusive Frozen Love perfume “translates the olfactory senses into a journey through the massif of the Fagaras Mountains, sculpting the fresh smell of nature”); and the Sorrisniva Igloo Hotel, Alta, Norway (snowmobile safari and dogsledding optional, “serenity and silence” guaranteed). The Snow Hotel in Kemi, Finland is more of a snow fort (optional three-hour Icebreaker Safari cruise includes a chilly swim).

***

Yet somehow, all these theme parks, winter carnivals and pricey hotels seem to exploit the ice palace concept more than embrace it.

Perhaps that was what Turkmenistan president Saparmurat Niyazov was thinking when, in the spring of 2004, he ordered the construction of a huge ice palace near the capital city of Aşgabat, in the heart of a central Asian desert.

Let’s make it “grand enough for 1,000 people,” he enthused on national TV. “Our children can learn to ski and ice-skate.” Niyazov, who’d been ruling with an iron hand since 1985, also ordered a giant aquarium stocked with tropical fish to be fixed atop the palace which, he insisted, would be linked to the capital by cable car. He estimated a construction schedule of 10 months. As to estimated cost, he was tight-lipped. Though rich in oil and gas reserves, Turkmenistan is among the world’s poorest countries.

“Mr Niyazov will become the first head of state in a post-Soviet government who has promised to teach children to ski in the desert,” quipped the Russian daily Izvestia. An allusion to pre-Soviet Russia? Perhaps Niyazov, who’d officially replaced the Turkmen word for “bread” with the name of his late mother and re-named the months and days of the week after other relatives, was thinking to honor Anna Ivanova by bringing back the ice palace tradition?

More likely, Niyazov was inspired by the 2002 James Bond Hollywood blockbuster Die Another Day, which featured a majestic, modernistic ice palace New York real estate broker Ryan Servant aptly described as the lovechild of McDonald’s arches and the Sydney Opera House. The villain Gustav Graves’ intricate ice mansion took nearly six months to construct, much of it formed from textured acrylic, less likely to melt under studio lights.

Gustav Graves’ ice palace

Though only modestly successful, the film did for ice hotels what Titanic did for the cruise industry; bookings hit an all-time high. Particularly blessed was Quebec’s Hotel de Glace. Opened in 2000, the only ice hotel in North America was built from 12,000 tons of snow, 400 tons of ice, and features (not surprisingly) a 007-themed suite with huge, swanlike bed and ice diamonds, a massive lobby ice chandelier, plus saunas and hot tubs under the stars.

Two years after proposing (nay, insisting on) his frozen-in-the-desert vision, Niyavoz died. His project vanished like a mirage.

***

250, even 150 years ago, such structures were otherworldly, phantasmagorical. But with all the entertainment options available today, from video games, MTV, and ultra high definition TV to Virtual Reality goggles, what is the enduring attraction?

Ice palace, St Petersburg, Russia

Consider.

Is building a meticulously rendered, life-sized palace of ice any more foolhardy than attempting to climb Everest, sail around the globe, or, like the late Christo, wrap islands and monuments in bright yellow and hot pink fabric?

More impractical than the forensic scientists obsessed with locating, at enormous expensive, the bones of genius “bad boy” Caravaggio, who disappeared in 1610? More dangerous than a sleep-deprived Philippe Petit, who walked, pranced and skipped 110 stories above Manhattan without a harness or net, having jury-rigged a wire between the World Trade Center’s towers in the dead of night?

Despite the tendency to “market” modern-day ice palaces with Disney-like razzle dazzle (corny music, candy-colored, nearly psychedelic lighting) in order to compete for our over-saturated attention, these immense, ephemeral, labor-intensive constructions remain emblematic of an often-lost sense of wonder, one far removed from the parameters of everyday life.

These immense, ephemeral, labor-intensive constructions remain emblematic of an often-lost sense of wonder.

Perhaps their ongoing presence comes, ultimately, to this: they remind even the least creative among us of the passionate quests of dreamers, without which all of history — past, present and future — would be so much poorer.