No, Rape and Sexual Harassment Aren’t “About Power”

By Gurwinder Bhogal

Staff Writer

17/1/2020

Rape of the Sabine Women by Sebastiano Ricci

Last week, an Indonesian student, Reynhard Sinaga, was convicted in the UK of 136 rapes of young men, making him the most prolific rapist in British legal history.

In response, Alex Feis-Bryce, CEO of a service that supports male rape victims, penned an op-ed in The Guardian, which he concluded by emphasizing that “Rape is not about sex or sexual attraction: it is about power.” This statement echoes an earlier Guardian article, by Claire Potter, Professor of History at the New School, who claimed: “Sexual harassment is about power. Why not fight it as we do bullying?”

The idea that rape and sexual harassment are “about power” is now the default explanation for such acts, and it is now so entrenched in culture that it underpins how such cases are taught in universities, treated in support groups, and even adjudicated in the courts.

But is there any actual truth to the idea? Given its prevalence, and the confidence with which authority figures repeat it, you’d think it would be backed by evidence. The problem is there is actually far more evidence that the claim is false, and that it’s dangerous to believe.

There is actually far more evidence that the claim is false, and that it’s dangerous to believe.

The notion that rape is about power was first given popular expression in Susan Brownmiller’s 1975 book, Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape, in which she claimed that rape is “nothing more or less than a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear.”

Brownmiller’s book became a bestseller and she became a star, with Time magazine dubbing her “the first rape celebrity who is neither rapist nor rapee,” and New York Public Library selecting Against Our Will as one of the 100 most important books of the 20th century.

The accolades heaped on Brownmiller’s book may suggest it was meticulously researched and irresistibly argued. Unfortunately, it was neither. The book rarely backed up its assertions with evidence, and even when it did, it tended to misrepresent the evidence to fit a worldview.

One example is rape in animals. Brownmiller claimed that to her knowledge, no animal has ever been observed to rape in its natural habitat, and that this is evidence that rape is a cultural rather than natural phenomenon. But this is misleading; claiming an animal has never raped is like claiming an animal has never committed murder; it is a category error that leads to circular logic because murder is by definition a human killing a human. Rather than look for rape in animals, it is more useful to look for rape’s zoological analogue: forced copulation. And this has long been known to exist in the animal kingdom, from insects all the way up to our closest relatives, which Brownmiller would have known even in 1975 had she conducted sufficient research.

Nevertheless, Brownmiller’s ideas quickly spread among the intelligentsia, and today they’ve evolved into the more general notion that rape is motivated not by a desire for sex, but a desire for power. The scope has also been widened to include sexual assault and sexual harassment. But is this more sophisticated formulation any truer than Brownmiller’s?

Psychoanalyst Lyn Yonack wrote that “when someone rapes, assaults, or harasses, the motivation stems from the perpetrator’s need for dominance and control.” She supported this statement by pointing out that most instances of sexual misconduct and abuse “arise within asymmetrical power dynamics, where the perpetrator occupies a more powerful or dominant position in relation to the victim.”

It’s true that sexual abuse tends to follow power gradients; bosses sexually harass underlings far more often than vice versa, adults sexually abuse children far more often than vice versa, and the most egregious acts tend to be perpetrated by those with a great deal of power, like Jeffrey Epstein and Harvey Weinstein. But this is not proof that rape and sexual harassment are motivated by power; it’s proof that they are facilitated by power since obviously it’s far easier to rape or sexually harass someone you have power over.

Furthermore, if rape or sexual harassment were indeed motivated by the desire to feel powerful, then one would expect them to be less common among those who already feel powerful, and that they would more often go against the power gradient rather than along it; that is to say, raping or sexually harassing someone more powerful would have greater appeal than sexually abusing someone less powerful.

Tarquinius and Lucretia by Hans von Aachen. It depicts the rape of the noblewoman Lucretia by Tarquinius, prince of Rome.

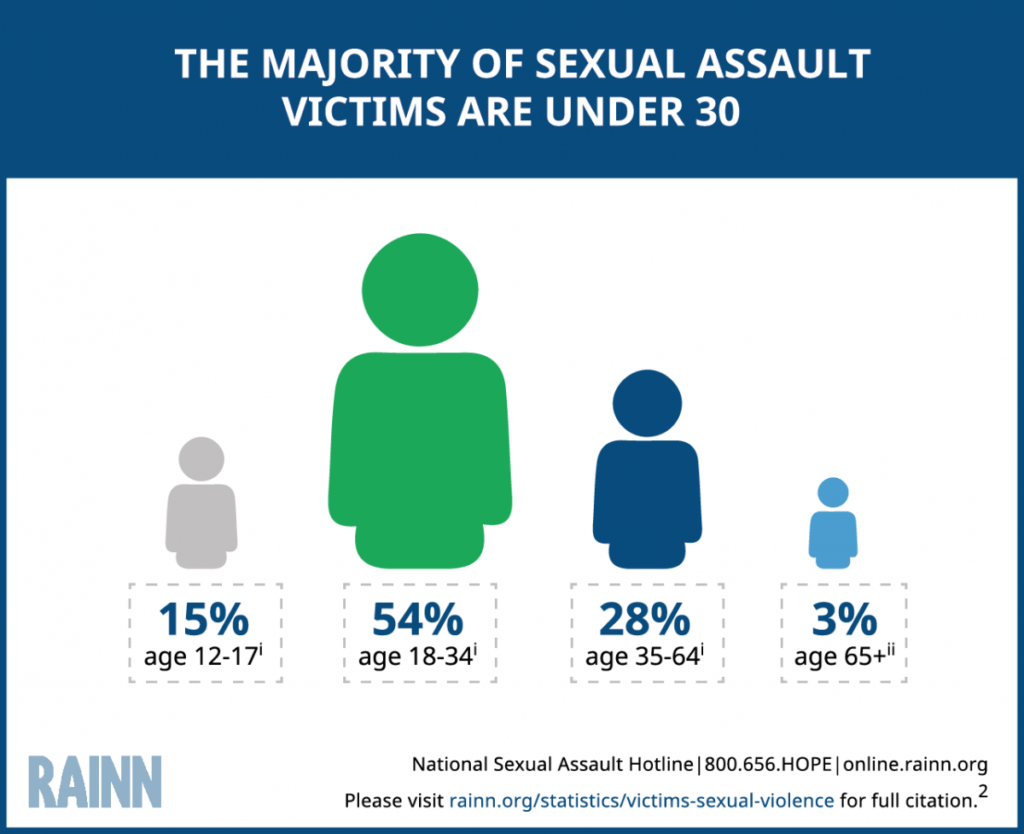

In fact, the women most likely to be sexually abused are not those with the most or least power, but those of the most fertile child-bearing age. In a study of 250,000 rapes and sexual assaults, sociologists Richard Felson and Richard Moran found that the overwhelming majority of victims were young, with a 15-year-old female nine times more likely to be abused than a 35-year-old female. This disparity cannot be explained by the very young being easy targets, because the equally helpless very old are rarely the victims of sexual abuse. It makes sense only if the young are preferred by abusers because youth is correlated with attractiveness and fertility. Likewise, statistics compiled from the US Department of Justice by the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN) show that the majority of sexual assault victims (54%) fall between the ages of 18-34, the age band in which people are usually considered most attractive.

Felson and Moran also found that, while victims of sexual abuse are overwhelmingly young, abusers themselves tend to be older than men who commit other violent crimes. This is hard to explain if sexual abuse is motivated by a desire for power, but easy to explain if it is motivated mostly by sex (and older men commit these acts because their sexual attractiveness has declined but their sexual desire has not).

Another finding of Felson and Moran’s study was that homosexual men are just as likely to sexually abuse men as heterosexual men are to sexually abuse women. Indeed, every one of the 136 rapes committed by the openly gay Reynhard Sinaga was of men. This again suggests that sexual abusers are primarily motivated by sexual attraction toward their victims.

Now, it could be argued that people sexually assault those they are sexually attracted to not simply because they want to have sex with them, but because for some deranged reason they want to see the object of their desire suffer. In her article, Rape is About Power, Not Sex, lawyer and feminist Jill Filipovic proclaimed:

“Rapists don’t rape because they can’t “get” sex elsewhere. Rapists don’t rape because they’re uncontrollably turned on by the sight of some cleavage, or a midriff, or red lipstick, or an ankle. They rape because they’re misogynist sadists.”

However, it should be noted that the vast majority of convicted rapists fall short of the clinical criteria required for sadism. Most experiments into the sexual arousal patterns of convicted rapists, like those of Quinsey et al. and Harris et al., have found that rapists tend to be aroused by simulated sexual violence but not simulated nonsexual violence.

Many rapists also try to hide their assault from the victim. Sinaga only managed to become Britain’s most prolific rapist through stealth. He would wait outside nightclubs for drunken men, whom he’d lure back to his apartment, where he’d drug them unconscious, and then rape them. It was only after one of Sinaga’s victims awoke mid-rape and managed to fight him off that his crimes came to light.

Reynhard Sinaga

The fact that men like Sinaga sexually assaulted their victims only after they were unconscious suggests that sexual assault is not motivated specifically by a wish to inflict suffering on the victim, but rather, a wish to elicit pleasure in the rapist even if the victim feels nothing at all.

There are of course some abusers for whom part of the appeal of sexual abuse is the suffering of the victim. But it should be noted that even in these cases, sadism is usually only the proximate cause, while sex is the ultimate cause, because the sadism is typically a paraphilia that results in ejaculation. Thus, even in the cases in which sexual abuse is about power, power is usually about sex.

It should by now be clear that sexual misconduct and abuse are about sexual attraction far more than they are about power. But if all it takes to demonstrate this is a few paragraphs of text, why does the world still believe the myth? How did such blatant falsehood escape the realm of fantasy, bypass the burden of proof, trespass into courtrooms and lecture halls, and usurp the truth?

One explanation is the “Woozle effect,” a phenomenon whereby frequent citations of a work eventually create the impression that the work is established fact, leading to it being cited even more, perpetuating the impression.

The term “Woozle effect” comes from an episode in A. A. Milne’s book Winnie-the-Pooh, in which Pooh and Piglet follow tracks in the snow, believing they are on the trail of a creature called a woozle. The tracks keep multiplying until someone tells them they’ve been following their own tracks in circles under a tree.

But in order to so utterly dominate the debate, the idea must have some inherent appeal, and in this case, the appeal is likely political convenience. For many it is preferable to believe that our worst failings result from culture and not nature, because we can change our culture but generally not our nature. If sexual misconduct and abuse are a result of learned male entitlement, then we can simply educate men to be less entitled. But if they’re largely a result of unrestrained male libido — too primal to be fully amenable to cultural remedies — then they have no easy answers.

Furthermore, believing sexual misconduct and abuse is about power ostensibly has greater social utility than believing it is about sexual attraction. The most common argument against the idea that sexual abuse is about sexual attraction is that it takes the blame off the abuser and shifts it to the victim for dressing provocatively or generally being too sexy. But this is nonsense; to say that sexual abuse is largely about sexual attraction does not in any way diminish the responsibility of the abuser. Explaining behavior is not excusing it. We can simultaneously recognize that a rapist was motivated by the need for sexual gratification and acknowledge that he is morally culpable for not controlling his urges.

To say that sexual abuse is largely about sexual attraction does not in any way diminish the responsibility of the abuser.

Radical feminists who see danger in the belief that sexual misconduct and abuse are about sexual attraction should instead look at the far greater dangers of believing they’re about power. For instance, this belief has a seductive but perilous corollary — if rape is a conscious act of oppression, then someone can’t be guilty of rape if he just wanted sex — an argument that many a rapist would make to himself to alleviate guilt, and that many a victim will make to herself to exonerate her rapist.

In the end, though, the biggest danger of the “sexual abuse is about power” claim is that it’s simply not true. No matter how well-meaning or socially useful a lie may seem in the short term, in the long term it will always pose a threat, because by its nature it estranges us from reality, and causes us to build our systems on illusory foundations.

If we want to combat rape and sexual harassment effectively, then we must be honest about their causes. We’ll have to overturn the mythology that has developed around these destructive acts, and acknowledge that while they may sometimes be about power, the evidence is unequivocal that they are above all about sexual attraction. There may be no simple answers to unruly libidos, but ultimately a difficult solution to the real problem will always be better than an easy solution to a false one.