Our Royals

By Thomas Lambert

Staff Writer

6/5/2021

In a 2019 leadership debate with Jeremy Corbyn, Boris Johnson made a curious comment. Asked in the wake of recent sexual abuse allegations about Prince Andrew about the fitness of the monarchy for purpose, he replied, with a stoical grimace: “The institution of the monarchy is beyond reproach.”

The national reaction was very strange. Britons, steeped in the partisan punditry that has always attended the House of Windsor, might have been expected to react with predictable binarism: enthusiastic monarchists unfurling their Union Flags on one side, incensed republicans sharpening their guillotines on the other. Instead, however, Boris’ remark was met with a kind of universal bemusement. It seemed evasive, everyone agreed; perhaps even sophistic. The institution of the monarchy? What on earth could that mean?

The truth, of course, was that Boris had poked at a reality about British constitutional life that the UK’s populace has long repressed. It’s a truth that lurks behind the weddings and jubilees, behind the Duchy of Sussex’s recent departure, behind the teary eulogies to Prince Phillip. The institution of the monarchy no longer exists.

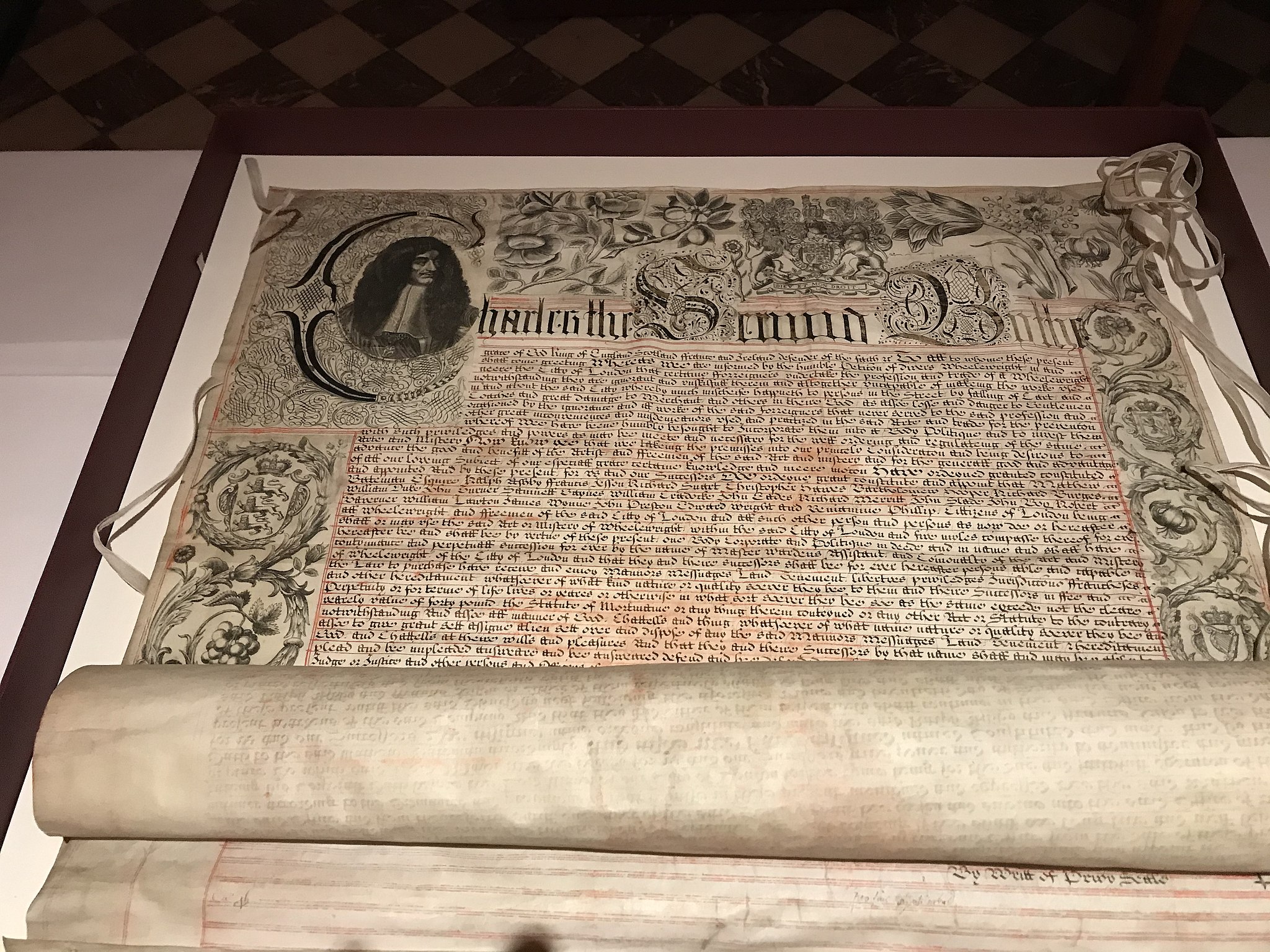

What is a monarchy? In antiquity, the monarch was a point of contact with the divine, the highest human link in the great chain of being. Like the emperor in Kafka’s “The Great Wall of China,” he was a figure infinitely remote from ordinary people, infinitely aloof. With the Enlightenment came a new conception. The monarch was no longer the guardian of feudal privileges for a clutch of barons, but the guarantor of a new kind of commons: royal charters empowered the crown courts, organized the royal mail, endowed royal academies and institutions. George Orwell, in his flintily traditionalistic essay “The Lion and the Unicorn,” noted the perverse egalitarianism of the whole scheme. We are subjugated, but in a perfect, universal way; the monarch is us, and we – with street parties, our commemorative crockery, our red, white, and blue bunting – are her. It’s only natural that in the UK the fundamental modern civic unit is neither the citoyen, as in France, nor the Staatsbürger, as in Germany (nor even, as appears to be the case in the US, the “taxpayer”) – but the “subject.”

Royal Charter given by Charles II to the Guild of Wheelwrights in 1670

Except, of course, it doesn’t quite work like that anymore. It takes no great sociological insight to realise that our rights are derived from the crown in name only. The “royal” designation is an atavism, a hangover; most “royal” institutions survive on some combination of reluctant handouts from elected governments and glitzy corporate sponsors (the website for the Royal Institution – a chartered organisation for scientific education and research that has stood fast since 1799 – lists over 30). If asked who represents them, meanwhile, Britons are more likely to cite at best an elected MP, or at worst a celebrity with whom they have some peculiar identification.

And yet, in Britain, the royals are still, undeniably, ours: our Queen, the People’s Princess, our Wills and Kate, our brood of photogenic royal babies. Where once we Britons spoke of “our” monarch the way we might speak of our nation, now the phrase has the ring of property – our infinite source of entertainment, our plaything, our pet. In an age of privatization and sale of public effects, the royal family, curiously enough, is the closest thing the UK has to an asset genuinely held in common. This is the salient fact about the British monarchy today that any interested foreigner must grasp. The royals are the commodity of which we all may partake: the res publica, the public thing.

Where once we Britons spoke of “our” monarch the way we might speak of our nation, now the phrase has the ring of property – our infinite source of entertainment, our plaything, our pet.

That the monarchy has become commodified is not a completely new insight. In a way, royalty has always been self-commodifying, in the strict Marxist sense: all the pomp and pageantry is designed to paper over the mess of relations that comprise it in one overarching political abstraction. In recent years, however, an independent media has started doing the monarchy’s job for it by cultivating its glamor and mystique. Conservative writer Theodore Dalrymple was one of the first to observe this phenomenon when he wrote of the “Dianafication” of British life in the wake of the princess’s death in 1997. The public wailing, the mountains of stuffed animals, the jowly dirges of Elton John: these were not spontaneous outpourings. All were fomented and amplified by a media which had just discovered its audience’s ravenous appetite for kitsch. For the media, glamorizing the royal family had become – and remains to this day – a sensible investment: every sprog, every spat, every substantial fascinator becomes the kernel of a new piece of “content,” a new story.

2021 Daily Mail story on Princess Diana

Enter Meghan Markle. In several ways, Meghan is admirable (impressively educated, predictably philanthropic), and if the Harry-hagiographers are to be believed, she’s been something of a breath of fresh air in an otherwise fusty and repressive royal household: “Meghan and Harry,” gushed Caitlin Flanagan in The Atlantic, “met when he was in the midst of a reevaluation of his life and a growing understanding of how much of it had been shaped by the profound trauma of his childhood.”

Meghan Markle and Harry

Yet the salient fact about Meghan is not how different she is from the royals into whose pit of emotional inhibition and veiled racism she was parachuted, but how similar she is to what royalty means today. This is the great truth that coverage of the Sussexes’ departure has been missing. Meghan wasn’t bringing celebrity culture to a recalcitrant institution; in every meaningful sense – in their relentless commodification by the media, in their grotesque symbiosis with public prurience, in their unacknowledged status as common property – the royal family were celebrities already.

Understanding this fact is key to understanding the great animus Meghan Markle has provoked. She’s not radically different from her illustrious in-laws – just slightly less white, slightly less aristocratic, and, like Ms Simpson before her, American, and therefore, in the British conservative imagination, almost axiomatically shallow. The observant royalist has long suspected that the monarchy is no longer about heredity and cultural continuity, but about gossip, celebrity, and the vagaries of PR; now Meghan arrives, fresh from California, and wants to be a princess. Like a picture of Major James Hewitt placed alongside Prince Harry, her presence helps highlight the truths about the Royal Family that we’ve known at the back of our minds all along. The vitriol is inevitable. Meghan Markle made it obvious that what we thought was an institution is now just a spectacle. Meghan joined the monarchy, and it ceased to exist.

Yet almost no-one acknowledges this basic similitude. The narrative has crystallized: the monarchy versus Meghan; heredity versus new money; old and stuffy and white versus young and vivacious and black. The Sussexes are a new kind of royal, we’re told; they check their privilege; they schmooze and mope with Oprah. The need to perpetuate this narrative, to expand it and amplify it, has led to some beautifully vile moments. Consider Meghan’s message to young women in the Commonwealth: “Growing up, as a woman of color, as a little girl of color, I know how important representation is; I know how you want to see someone who looks like you in certain positions…How inclusive is it that you can see someone who looks like you in this family, much less one who was born into it.” Perhaps, hopes Meghan, young girls in Rwanda can look at her and aspire to marry a prince of the land that once colonized them. We can only dream.

Such unspeakable crassness does help us realize how absolutely negative and hypocritical the whole spectacle is (without even having to dredge up the old favorites: Harry in his Apache helicopter gunship over Kandahar, Harry in his Nazi uniform). There is no emancipatory opportunity here, no struggle of progressive versus reactionary values: both sides of the schism are manufactured to perpetuate the story, the saga, the soap opera that never ends. The Crown spills seamlessly into the news cycle, and we all keep watching. This is why the progressive press’ hysterical support for the Sussexes’ every piety is so misguided. The philosopher Herbert Marcuse wrote in the 1960s of a phenomenon he called “repressive desublimation:” every form of dissent, critique, independent thought is capable of being commodified and co-opted to reactionary ends. We may think that in demonstrating our support for Meghan and Harry we’re dealing a blow to entrenched privilege and prejudice, but really we’re buying into its latest incarnation. “The music of the soul,” as Marcuse put it, “is also the music of salesmanship.”

Both sides of the schism are manufactured to perpetuate the story, the saga, the soap opera that never ends.

Nevertheless, pointing out the true meaning of “Megxit” only tells half the story. Indeed, the great deficiency of Meghan-skeptics like Piers Morgan has been to blend a justified revulsion at the whole spectacle with a condemnation of its two protagonists as insincere. But, in a way, Meghan and Harry should be applauded. Amidst their pieties, their fatuities, their absurdities, they seem to really believe they’re doing the right thing. Somewhere beneath the sound and the fury, “the music of the soul” plays gallantly on.

There are even occasional glimmers of insight: when Meghan confessed that “There’s the family, and then there’s the people that are running the institution,” for instance, or when Harry staggered to the conclusion that “the rest of my family…my father and my brother, they are trapped.” But these realizations were reached not in some Beverley Hills therapy session or some private beachside tête-à-téte with her inner circle, but on Oprah; they were the latest and most spectacular chapter of the saga in which Meghan and Harry are imprisoned. So when Meghan resurrects George VI’s moniker of “The Firm” to describe the extended royal household, she really believes she’s dealing a blow to a structurally unjust institution; but the institution she’s referring to doesn’t even exist. Instead, Meghan has simply identified her antagonist in the media circus on which royalty depends, and which for the last four years has been slowly but tenaciously ruining her life. Meghan is part of “The Firm,” but she doesn’t know it.

The tragedy, in fact, is that Meghan and Harry seem to have bought into the royal myth. Like Diana before them, they’ve absconded from the family, but still seem set on carving out a career as members of the international glitterati. In doing so, they seem to think they can acquire a new kind of autonomy: the kind that comes with tv show appearances, private jets, friends in high places. But Hollywood royalty is still royalty; they remain commodified, their lifestyle supported by sheer force of attention rather than any kind of institutional power. And quite soon – probably the moment Prince George, Princess Charlotte, Prince Louis come of age – Meghan and Harry will find themselves sidelined. They will become peripheral figures, wheeled out at Ascot, then pushed back into obscurity with the other forgotten victims of divorce and primogeniture: the Sarah Fergusons, the Beatrices, the Eugenies.

The Queen and Prince Philip at Ascot

Or, of course, Meghan and Harry “win.” Perhaps the Queen really will represent the last generation of icy stoicism, the stiff upper lip for which the British are so undeservedly admired. Perhaps subsequent royals will come to share and espouse Meghan’s touchy-feely brand of Californiana. Perhaps they’ll “check their privilege.” Perhaps they’ll go on Ellen, do juice cleanses, swap Balmoral for silent retreats in some ashram in a former colony. Perhaps – and already, the prospect seems eminently possible, infinitely marketable – some cataclysmic event, like the death of the Queen, will precipitate a rapprochement. The Sussexes will tearfully make up with William and his progeny, and usher in a “new kind of monarchy” with all the pomp and self-congratulation of 1215 or 1688.

The monarchy may be set for this kind of postmodern revolution. In the Sussexes’ tribulations we encounter the next wave of “Dianafication” – of royalty as an item held in common, a plaything, a national pet for us to in turns revere and deride. Will the monarchy survive? Will royalty retain its cachet? Will the Queen be our last hereditary head of state? Already the questions swirl around, the silt of public opinion disturbed by each new crisis, each new death. But the damage was already done sometime in the 20th century, somewhere in between WWI and the liberal wave of the 60s. The reaction to Diana’s death was proof of this, and the spectacle of Megxit confirms it. The monarchy is over. The Windsors belong to the media now. Only by our attention and our indulgence are they kept from the obscurity they so richly deserve.