Shunga: Beyond “Edo Porn”

By B. Alexandra Szerlip

Contributor

9/11/2020

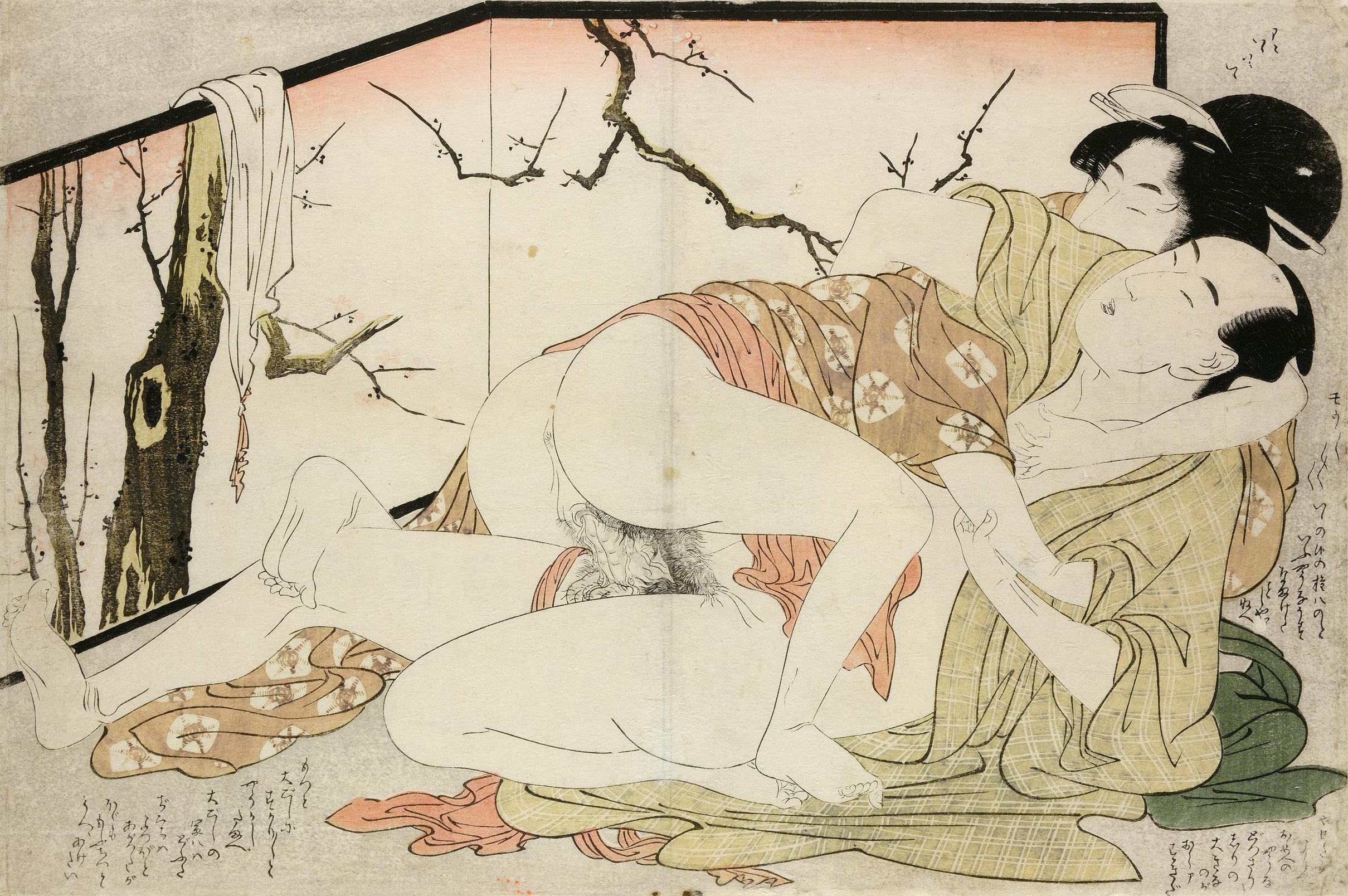

Print by Kitagawa Utamaro (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Life in 16th-century Japan was riddled with famines and civil wars. The Edo period (1603-1868), which followed, ushered in two and a half centuries of extended peace, and with it, a profound cultural shift. Precariousness and fear were left behind, replaced with the pursuit of pleasure: attending wrestling matches and plays, taking ferry rides, enjoying picnics and festivals.

The vernacular, too, was shifting. Ukiyo, which began as the Japanese interpretation of the Sanskrit word samsara, with its focus on suffering and mortality, flipped in meaning from fatalism to hedonism. Then, following the publication, and enormous success, of Asai Ryoi’s Tales of the Floating World (Ukiyo Monogatori), which included long, poetic appreciations of courtesans, the floating world — “floating,” as distinct from the “fixed” world of daily life and obligation — became inextricably linked, in people’s minds, with yukaku, Japan’s red light districts, with ukiyo-e (artistic expression inspired by the floating world), and a distinctive subgenre of ukiyo-e known as shunga.

Shunga (literally “spring pictures”) was, noted scholar Timon Screech, a Chinese-inspired euphemism meant to disguise what the images were really about; in legal writings of the period, they were known as koshoku-bon (sex books) — highly erotic paintings and woodblock prints characterized by meticulously detailed genitalia, astonishing (if not impossible) physical contortions, and occasional witty dialogue or commentary.

Print by Kitagawa Utamaro (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Originally commissioned by the wealthy, produced in hand-colored editions on the finest paper, with lacquered covers and exquisite bindings, shunga depicted a world of sexual wish fulfillment. For some, the prints were the closest thing to visiting Yoshiwara, the capital city’s most famous brothel district, in person.

Along with elaborate kimonos (partners tend to be nearly fully clothed), sumptuous, colorful quilts, and garden-variety coitus, there were vivid depictions of “69” (mutual oral sex), cunnilingus, fellatio, anal sex and finger probing, threesomes, and considerable voyeurism. Penises were often greatly exaggerated in size — a “style” not found in classical Chinese or Indian erotic art.

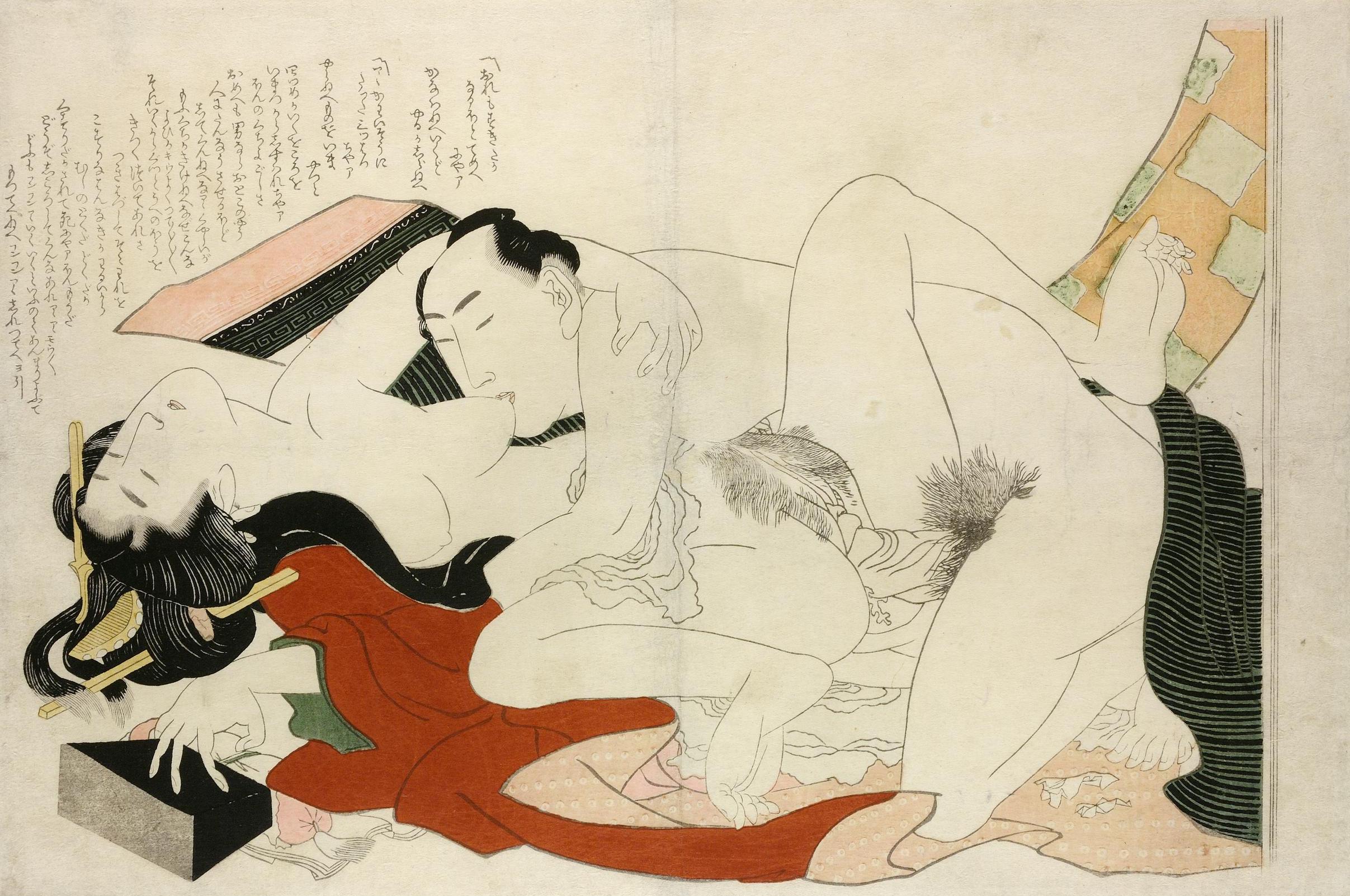

Print by Kitagawa Utamaru depicting a courtesan slipping out of a boring party to be with her favorite lover (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Assignations took place in graveyards, in gardens, on balconies and small boats, in the cupboards of busy restaurants. Husbands mated with their pregnant wives; old men seduced adolescent girls. Some images included sex toys or couples looking at shunga prints during (or in anticipation of) the sexual act.

There were “domestic” scenes, too. A couple having sex while he nonchalantly prepares his tobacco pipe. A fornicating couple entertaining a child with toys and puppets. A geisha playing a samisen and singing while straddling a customer.

By the late 17th century, woodblock printing and superior inks had largely replaced expensive hand coloring, resulting in an explosion of mass produced materials. In the past, shunga had been restricted to the libraries of wealthy samurai (and the dowries of their daughters). Records show that women of all classes, whether married, widowed, or single, now sometimes purchased shunga for themselves. (Along with sexual imagery, shunga’s depiction of fashions and hairstyles, its kabuki references and inside jokes, were also a lure.) The prints were often taken into battle by soldiers as good luck talismans.

Records show that women of all classes, whether married, widowed, or single, sometimes purchased shunga for themselves.

More than simply erotica, shunga was enriched, from its very beginnings, with layerings of ribald humor, wordplay, literary references, and parodies aimed at the cognoscenti. Appreciating the complex iconography required an educated mind. In other words, shunga was uniquely highbrow.

Print by Kitagawa Utamaro, plum trees in blossom on the screen alludes to sexual pleasure (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Though shunga could sometimes be controversial (e.g. a widow at a Buddhist temple being ravished by a priest), official objections were often non-sexual in nature. One book was censored for showing “the mixing of classes,” another for revealing too much detail about the layout of an imperial palace. Otherwise, the prints and books were largely legal and unregulated until 1722, when the Japanese government banned commercial vendors from selling them. As with all forbidden fruit, shunga became all the more sought after, its sale more surreptitious.

***

But by the early 19th century, many fans had become de-sensitized; the novelty had begun to fade. Artists (and their publishers) responded by reinvigorating the genre through the use of state-of-the-art printing methods (vivid colors, books with flaps that moved to reveal hidden imagery, even articulated paper puppets); by incorporating subject matter from popular culture (with an emphasis on the supernatural); and by taking on ever-more-taboo subject matter (rape, lesbianism, necrophilia, bestiality).

Painting by Utagawa Toyoharu depicting maids being raped by workmen (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Another bout of official censorship, around 1840, served to attract some of Japan’s greatest talents, most of whom remained anonymous. Utagawa Kuniyoshi signed his work by painting in a cat and calling himself “The Wondrous Pussy.”

Elaborately rendered pubic hair became a mainstay. 21st-century shunga experts believe that pubic hair was, in fact, an opportunity for out-doing one’s fellow artists, an intricate “signature” by which otherwise unsigned prints can sometimes be ascribed.

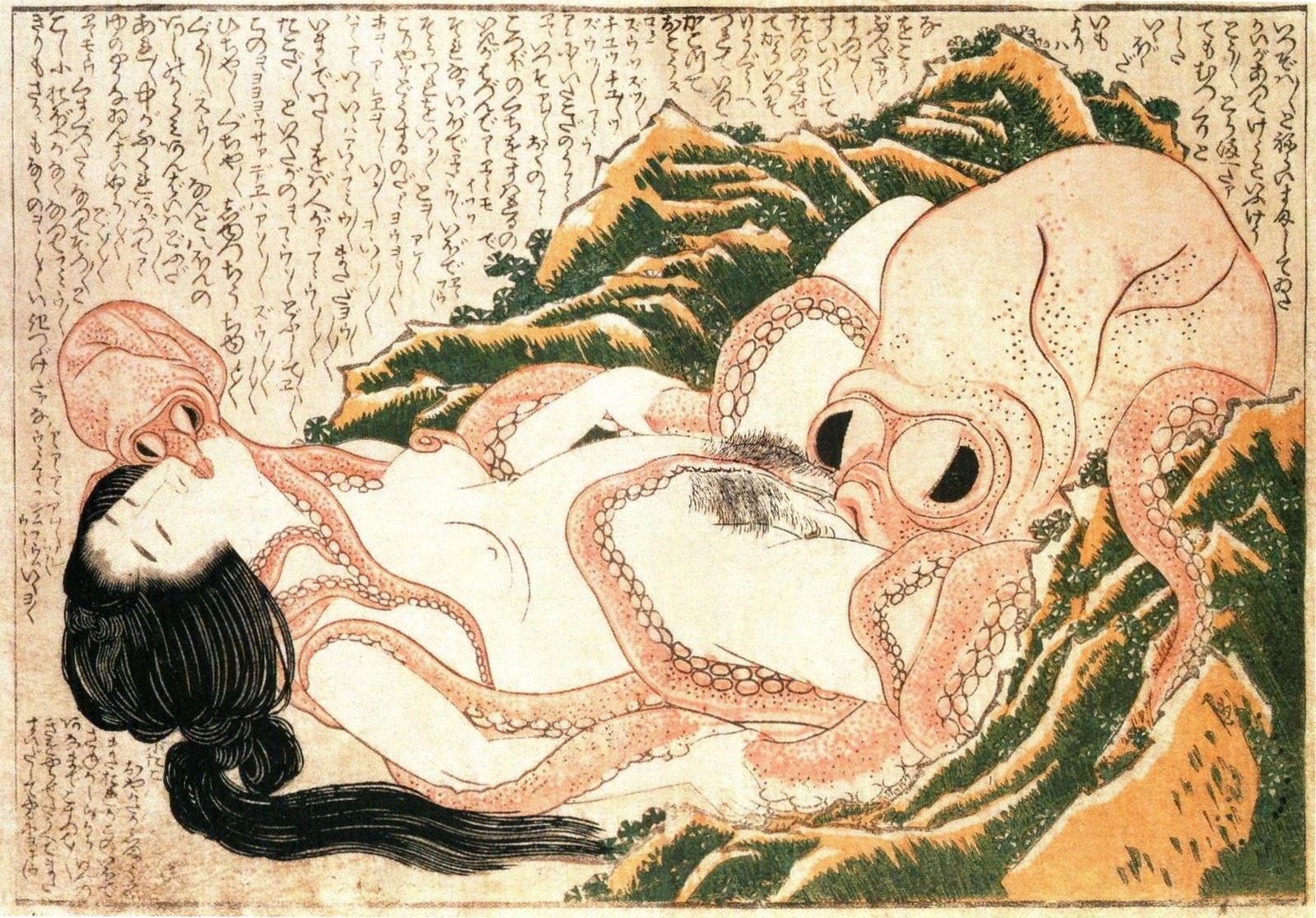

Print by Katsushika Hokusai (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Creativity and cleverness were bywords. Images were soon replete with ghosts, demons, and randy goblins, some with penises and vulvas for faces; print titles were often bawdy puns on demons’ names. Genitalia were also portrayed as maps or geological formations.

Print by Kitagawa Utamaro depicting an ama (a female pearl or abalone diver) being raped by kappa (water demons) (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Literary allusions continued apace. A Kuniyoshi print, sometimes referred to as “the gang rape” (believed by Japanese art historian Stephen Salel to be an orgy) is an elaborate parody of an earlier Kuniyoshi print, both based on the legend of four celestial guardians vanquishing the Earth Spider demon. In the first version, one soldier guardian wields a tree branch to tear the spider’s web, one a rope to lasso the demon, one a torch to burn it, another a sword to stab it. In Kuniyoshi’s ribald “re-do,” the Earth Spider demon is personified by a woman lying on the ground. The man with his finger inside her sex stands in for the soldier with the tree branch, the soldier with the rope now uses it for auto-erotic bondage, the torch has become a candle (for better viewing), the sword a different kind of “weapon.”

Prints by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (original, top, parody, bottom)

Though dogs, oversized mice and broad-winged bats can be found “having their way” with humans (usually human females), nothing — not even the Greek myth of Leda and the swan — compares with the visual impact of Hokusai’s’ Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814), the most infamous of erotic Japanese prints.

The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife by Katsushika Hokusai

In it, an octopus performs cunnilingus on a naked woman who lies on seaweed-covered rocks (one tentacle appears to curl around her clitoris), while a second, smaller octopus (its son) concentrates on her mouth and one nipple. The woman (described as an ama, a female pearl or abalone diver) swoons with pleasure, something the comical surrounding calligraphy makes clear. (A plump, good pussy. A greater delicacy than even a potato…Juices are flowing like hot water.)

Japanese viewers of “tentacle erotica” (Hokusai had been inspired by the earlier, 18th century work of Kitao Shigemasa and Katsukawa Shuncho) would have been aware that tako (octopus) was slang for vagina and also familiar with Taishokan, an ancient tale about a captured Buddhist pearl that was subsequently rescued from the Dragon King’s lair by an ama. Last but not least, there’s the wordplay of onkyo (the blessing given to the ama after the return of the jewel, one she tells the priests she’s dreamt of for years) and inkyo (octopus penis).

Humor was so often an element that shunga were known as warai-e (“laughter pictures”) and abuna-e (“dangerous pictures’) — dangerous as in provocative and risqué, not dangerous to society. “Whenever you look at these splendid pictures,” wrote 18th century artist Komatsuya Hyakki, “you cannot fail to smile. When you are stressed, shunga are best.”

Oh, I’m envious! by Tomioka Eisen

The extremely popular 18th century etiquette manual, Greater Learning for Women (Onna Daigaku), which emphasized subordination to one’s husband, was lampooned (with the swapping of an extra character in the title) to Intense Pleasure for Women (Onna Dairaku), and “updated” with correspondingly provocative images.

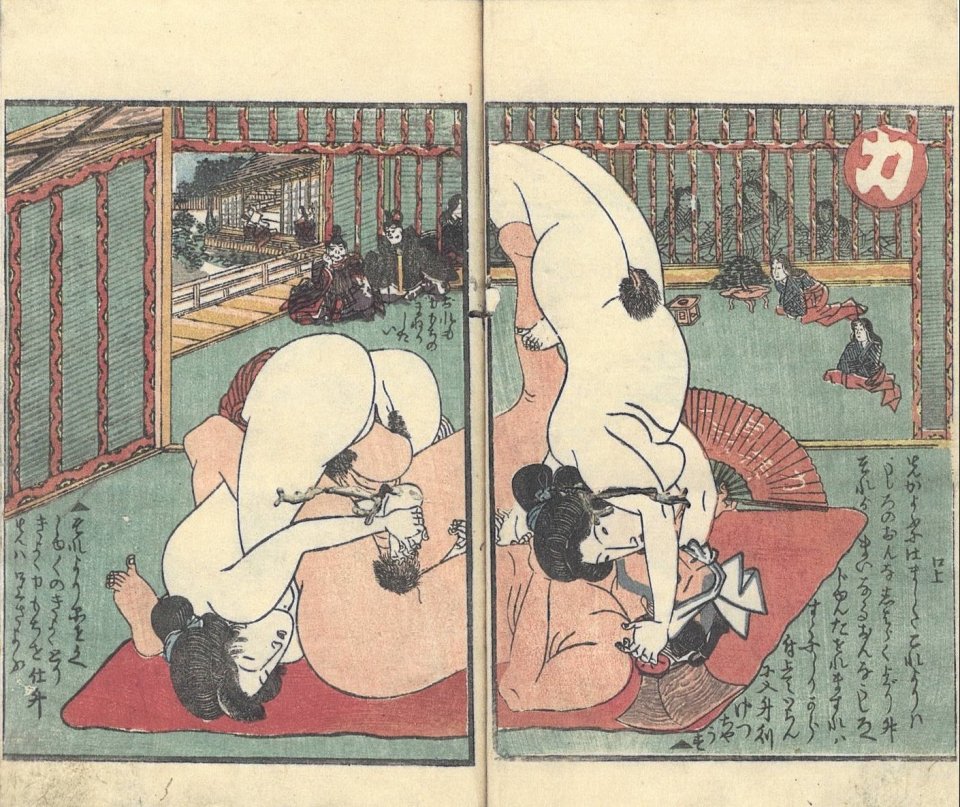

One print in Kuniyoshi’s Harbor of Love on the Island of Women series (Koi no minato-nyogo no shimada) – a parody of a 1680s Ihara Saikaku work – features two exceptionally limber women, both upside-down, “servicing” a man whose foot seems to be wedged in one of their buttocks. Another Kuniyoshi series shows half-naked women performing acrobatic stunts on a ladder, a parody of the acrobatics performed by firefighters at festivals.

Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

In a Gulliver-like print, a team of Lilliputian men try to pull down mythical warrior Kobayashi Asahina’s enormous erection with ropes. In another, blatantly sacrilegious image, Asahina is amused by a young boy who sticks his erect penis through a screen, creating the “nose” in a portrait of Daruma (a legendary Buddhist monk). In More Fun With Raccoon Dogs (Aratamete tanuki no tawamure), which plays on the belief that raccoon dogs could enlarge their scrotums at will, scrotums are reimagined as absurdist tools for making mochi (glutinous rice cakes), as fans for flailing the air to get streamers aloft for Boys’ Day, as dwarves’ heads and so on.

***

Censorship crested again in 1853, following the arrival of American Commodore Matthew Perry and his four ships into Tokyo Bay, bringing the same Western missionary values that had recently coerced traditionally bare-breasted Hawaiian females into shapeless muumuus.

One of the first civilian Westerners to arrive in the newly opened port was American businessman Francis Hall, who recorded several encounters – in shops, in private homes – with “vile pictures executed in the best style of Japanese art.”

Perhaps if they hadn’t been quite so beautiful? But ultimately, it was the open mindset, so un-Victorian if not un-Christian, that early visitors found most discomfiting, particularly when it came to their Japanese hosts’ “seemingly proper” wives, who were “entirely unashamed in viewing erotic art” in the presence of other men, something Hall described as “The depraved taste of this people, to the ordinary decencies of life.”

Voyeur maid masturbating, attributed to Isoda Koryusai (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Another early visitor, Captain Reinhold von Werner, a Prussian in the German army, noted that shunga and sex toys were sold openly, and that “even a child of ten is familiar with a secret of sexual love that elderly ladies in Europe had no idea about.”

Von Werner noted that shunga and sex toys were sold openly, and that “even a child of ten is familiar with a secret of sexual love that elderly ladies in Europe had no idea about.”

A less-often discussed “disturbing” aspect was gender fluidity and cross-dressing. Many prints depict wakashu – young, biological males who adopt dress and hairstyles distinct from either sex – something not uncommon in pre-modern Japan, and not subject to legal sanctions. Wakashu were perceived as sexually desirable by both women and men. There are also a few instances of young girls dressing up as boys.

Not all Westerners were so easily shocked. Many shunga travelled to the West as part of a general interest in Japonisme (and, of course, in sex). Collectors included Audrey Beardsley, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Gustave Klimt, Auguste Rodin, John Singer Sargent, and Pablo Picasso. Over one hundred shunga paintings, amassed by Charles Bigelow, were shipped to the US in 1909, having somehow gotten high-level approval from both Japanese and American authorities; the collection is owned, today, by The Boston Museum.

***

Arguably, the most unsettling aspect of shunga, to the uninitiated, are its graphic depictions of clitorises and glistening labia.

“How odd a vision the female undercarriage can be” noted British design critic Stephen Bayley. Not that the male undercarriage (which he refers to as “dangly bits”) fares much better.

Print by Kitagawa Utamaro (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Breasts and penises (with the occasional fig leaf) are not uncommon in Western Art, especially statuary, but “the female undercarriage”? Other than Gustave Courbet’s voyeuristic The Origin of the World (1866) and Marcel Duchamp’s secretive, final work, Étant Donnés, a full century later (it depicts a nude woman lying on her back with her face hidden, legs spread, viewed through a peephole), there’s little to rival Utagawa Kunisada’s Vaginal Inspection (1837) or his comical Beanman and Beanwoman Prepare to Storm the Storehouse (1827), to name only a few graphically “gynecological” examples. (The latter played on the then-new technology of magnifying lenses imported from the censorious West.)

***

The imperial Meiji government, which took power in 1868, was eager to present a “modern” (i.e. Western) face to the world. The Ordinance Relating to Public Morals (Ishiki kaii jorei), enacted in 1872, consisted of 53 articles discouraging behavior considered contrary to decency, safety, and order. These included a ban on mixed bathing, tattoos, and the performance of ribald songs, as well as the sale or purchase of shunga and sex toys; perpetrators risked up to a year in jail and heavy fines. Even the nomenclature of shunga was scrutinized: “Laughter pictures” (warai-e) morphed into “ominous” or “monstrous pictures” (kaiga) in common parlance. As in the past, this led to more clandestine methods of shunga production and distribution.

In the spring of 1905, the government conducted another series of wide-scale arrests and raids. Undercover police ferreted out tens of thousands of prints, woodblocks, and ostensibly “normal” postcards (sukashi shunga revealed hidden images when held up to the light), all of which were confiscated and publicly burned. Meanwhile, with the advent of the Russo-Japanese War, a new subset of prints emerged depicting nurses and soldiers in flagrante delicto, as well as Japanese soldiers buggering Russian ones.

Anti-shunga laws remained “on the books” well into late 20th century. When shunga’s value as a source of scholarly research into early Japanese culture and history finally began to be recognized, two major collections were published in Japan. Sold in plain brown wrappers, they were priced exorbitantly (to dissuade younger buyers), and parts of the text and visuals were airbrushed out or covered with black strips. It wasn’t until the 1990s that collections began to be published without interference.

***

Things began to change, again, in 2013, thanks to the efforts of British Museum curator Timothy Clark, who mounted “Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art,” a breakthrough exhibit that came with the caveat that visitors under the age of 16 had to be accompanied by a guardian. It attracted 87,000 visitors, half of whom were female. That shunga focuses on (or at the very least, includes) women’s sexual pleasure (with private parts described as “treasure boxes” rather than the “cunts,” “twats,” “slits,” or “snatches” of traditional Western pornography), and appears, for the most part, to be predicated on harmonious, mutual pleasure, wasn’t lost on them.

Print by Kitagawa Utamaro (Picture Credit: British Museum)

Clark’s attempts to reprise the exhibit in Japan were blocked at every turn. Despite the fact the shunga was now readily available in book form, it still harbored a reputation in some circles as “Edo porn.” 20 venues (influenced by political pressure) turned Clark down, claiming that the images were inappropriate for children, that they might cause offense or contribute to the stereotype of Japan as a hyper-sexualized society, that such things didn’t belong in museums at all.

But when former Japanese Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa, scion of an ancient line of feudal lords from whom he’d inherited a formidable private collection, created an executive committee to push Clark’s agenda, the government was unable to stop him. In 2015, after what one Japanese periodical described as “much hand-wringing and controversy,” the British Museum’s 2013 show was reprised, for two weeks, in Tokyo’s relatively small Eisei-Bunko Museum (run by Hosokawa’s family). Getting in to see it sometimes required a 90-minute wait. The accompanying catalog, a handsome, three-inch-thick volume, was sealed with a strip that read: Please handle the book with due consideration and don’t allow it to be viewed by anyone under 18 years old (an age restriction two years higher than the British Museum’s), an admonition reiterated on the entrance tickets.

A subsequent exhibit in Kyoto featured images borrowed primarily from a Danish collector. The enormous public interest these showings generated wasn’t lost on the Tokyo National Museum, the most prestigious of the museums that had turned Clark down. To make amends, the trustees announced they would sponsor a major shunga exhibit at the upcoming 2020 Tokyo Olympics — ultimately cancelled (or at least postponed) by the COVID-19 epidemic.

***

Without looking at shunga, wrote sociologist and noted feminist Chizuko Ueno (author of The Theatre Under the Skirt, a history of women’s panties), one cannot understand traditional Japanese concepts of sexuality in general and gender in particular.

Beyond that, the disconnect between the abiding human obsession with sex (as old as mankind itself) and its persistent stigmatization in cultures across the globe, is food for thought.

In his review of the Tokyo exhibition, art historian Naoyuki Kinoshita wrote that “Shunga should get us to think about what human beings are.”

Isn’t that what art is all about?

Woman dreaming of erotic scene at the kotatsu (covered brazier) on a winter’s evening (Picture Credit: British Museum)