Sleeping with the Enemy

By Mahlon Meyer

Contributor

25/7/2019

Animation mocking the 2015 meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou (Picture Credit: Next Animation Studios)

Throughout the Japanese invasion and occupation of China, they fought, sometimes openly, sometimes covertly. The two parties, Nationalist and Communist, who were supposed to be fighting against the Japanese, ended up time and again fighting against each other.

They have a history of betrayal and deceit, of feigned alliances and covert assassinations, of deadly warfare and frustrating defeats. By the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the two sides continued to despise each other across the hundred miles of the Taiwan Strait for the next 50 years. By 2008, however, the Nationalists, or Kuomintang (KMT), had effectively become the pro-Beijing party in Taiwan. How did this happen?

Nationalist troops firing artillery at Communist forces during the Chinese Civil War

***

When Chiang Kai-shek retreated to Taiwan in 1949, together with 2 million soldiers, officials, and former landlords, he relinquished control of the Chinese mainland to an enemy he still insisted on calling “land bandits.” Over the next few decades, the Communists exterminated or marginalized the remaining Nationalists on the mainland who had been unable or unwilling to flee.

The Nationalists on Taiwan were perhaps equally brutal. The found themselves sharing the island with its local inhabitants – ethnic Chinese who had migrated there from coastal provinces centuries ago and now considered themselves a distinct people. These Taiwanese, as they came to be called, numbered some 6 million, and spoke a distinct dialect, Hokkien. Since they’d been colonized by Japan for 50 years, from 1895-1945, they were also heavily influenced by Japanese culture.

During the first generation, the Nationalists and their followers were almost entirely “mainlanders.” Constituting just a quarter of Taiwan’s population, they established an apartheid-like government, controlling the military, the police, and the schools. To consolidate their control over the island, the Nationalists proceeded to massacre 30,000 to 300,000 Taiwanese in the first few years of their rule. A period of martial law known as the White Terror, in which political opposition was heavily suppressed, descended over Taiwan for the next 38 years.

Pro-democracy leaders arrested during the Kaohsiung Incident, 10th December 1989

The Nationalists buttressed this with a vast educational apparatus that portrayed themselves as the bringers of traditional Chinese culture, a culture that was superior to that of the local Taiwanese. In this narrative, Taiwan was relegated to a mere staging ground for the Nationalists’ eventual reconquest of mainland China. Until the formation of an opposition party in the 1980s, “education was designed to foster loyalty to the Chinese regime and affection for a Chinese homeland,” wrote Chang Bi-yu in Place, Identity, and National Imagination in Postwar Taiwan.

In other words, Chang and other scholars argue, the Nationalists’ propaganda of “taking back China,” not only kept their own nostalgia alive, but oppressed Taiwanese by teaching them their island had value only as part of that plan: a place without identity or meaningful history. “The desire to return to China laojia [homeland] was romanticized to encourage students to take on the role of ‘China diaspora,’ wrote Chang. “Paradoxically, in the KMT regime’s ‘making home’ on the island, the mainlander-dominated education made the islanders feel ‘homeless’ and like outsiders in their home,” she wrote.

This suppression of Taiwanese identity and dissent continued for decades. In 1979, however, the US recognized the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and abandoned the Nationalist government. In part to create a new legitimacy for their government, the Nationalists began to institute democratic reforms. Another reason for this was that by then the Taiwanese had worked their way up through the ranks of the military and now exerted considerable influence. Taiwanese leaders had also become increasingly assertive, opposing the government through activism, and beginning a long series of demonstrations in 1977.

In 1996, the Nationalists held Taiwan’s first presidential election, and won, beating the Taiwanese Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Just four years later, in 2000, though, the DPP won, ending 50 years of unbroken Nationalist rule over Taiwan.

This shook the Nationalists to their cores. The policies of the new government, led by President Chen Shui-bian, did little to soothe their fears. It had Taiwan’s textbooks rewritten. It renamed major roads, which had been named after Nationalist leaders. It pulled down statues of Chiang Kai-shek across the island. It also ordered Taiwan’s most prominent monument, the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall to be renamed “Taiwan’s Democracy Memorial Hall” in 2007.

New inscription is put on the gate of the memorial hall

The DPP also created a “Peace Memorial Day” to remember the event most associated with Nationalist violence, the 2-28 Incident. On February 28th, 1947, just as the Nationalist government was preparing to retreat to Taiwan, Nationalist policemen beat an old Taiwanese woman selling contraband cigarettes, sparking an island-wide protest. Chiang Kai-shek eventually sent soldiers from the mainland to crush the uprising, slaughtering thousands. Craig Smith, a historian at the University of British Columbia, in his paper, “Taiwan’s 228 Incident and the Politics of Placing Blame,” described these efforts by the DPP as constructing a “trauma narrative” with Chiang Kai-shek as the perpetrator. These policies hardened divisions between the original “mainlanders” and the “Taiwanese.” They also created confusion in children of mixed parentage, who wanted to call themselves “Taiwanese” but worried that their “mainlander” background might cast doubt on that.

Now it was the Nationalists’ turn to feel like aliens in what had come to be their own home. The DPP was now openly proclaiming that the mainlanders in their midst were no different from the Chinese Communists. Both were enemies. Both represented a corrupt and brutal China that the Taiwanese wanted no part of. This was, in the eyes of the older Nationalists, all part of a campaign not only to erase them from history, but to set them up for slaughter – just like what happened on the mainland 50 years earlier. “Chinese mainlanders,” wrote William Kirby, T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies at Harvard University, “could still feel abroad in their new Taiwan homes sixty years after migration.” Chou Chi-sui, chief of psychiatry at the Veterans General Hospital just outside Taipei, and himself from a prominent Nationalist family, said this gave many “mainlanders” post-traumatic stress disorder, making them relive the loss they felt when the Communists ousted them from China. “The second biggest event in the lives of these aging Nationalist leaders was the election of Chen Shui-bian to the presidency,” he said. “They felt again the shock of losing power and the foreboding of impending violence.”

Nationalist protestors took to the streets, carrying torches and beating drums, calling for Chen’s resignation. But Chen ruled for eight years, and the Nationalists, feeling increasingly alienated from their new home, began to look back across the Taiwan Strait at their former enemies. The ban on travel to the mainland had been lifted and many returned home to find long-lost relatives. Many of them began marrying women from China and bringing them back to Taiwan. By the end of Chen’s tenure, in 2008, first and second generation Nationalist men had married over 250,000 wives from mainland China, according to Taiwan government surveys. DPP politicians, for their part, lambasted the aging Nationalists for marrying women whom they said would influence them to support unification with China.

The Nationalists, feeling increasingly alienated from their new home, began to look back across the Taiwan Strait at their former enemies.

All this led to a growing sense of association with China. Having lost their identity as the saviors of Taiwan, they now sought a new one, by identifying with the success of the Communists across the Strait – it was also during this time that China experienced its greatest economic growth; from 2000-2008, China’s economy grew by roughly 10% a year. It was the one thing left they could feel proud of. They began to reassert their ethnic identity as Chinese. According to Chou, they began to say, “I am a Chinese, look at what the Chinese Communists have done, this shows how successful a Chinese, any Chinese can be.” Thomas Reilly, Professor of Chinese History at Pepperdine University, described the process as “mainland refugees reimagining their shattered identities.”

Beijing Olympics opening ceremony, 2008

Meanwhile, the Nationalists did everything they could to undermine Chen’s economic programs. The economy collapsed, and the Nationalists, led by Ma Ying-jeou, won the 2008 election, promising greater openness to China to boost the island’s economy. One of the first things Ma’s government did was to resume direct flights to the mainland for the first time in 50 years. Tourists, students, and investment from the mainland flooded into the island. Soon, Taiwan’s economy became massively dependent on the goodwill of China. Massive mainland investment in Taiwan’s media sector began to shape its news coverage.

Under Ma Ying-jeou’s administration, Taiwan’s economy became massively dependent on the goodwill of China.

The amity between the Nationalists and the CCP culminated in Ma Ying-jeou’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2015. “Turning military conflict into peaceful development has definitely not been an overnight effort,” Ma said, after shaking hands with Xi. An animation by Taiwanese Next Animation Studios called their meeting “a complete farce” and poked fun at the two leaders by depicting them walking hand-in-hand by a swimming pool and drinking wine together in a bathtub.

Ma Ying-jeou with Xi Jinping in Singapore, 7th November 2015 (Picture Credit: 總統府)

A backlash came in 2016, with the DPP, led by Tsai Ing-wen, returning to power. Tsai, a strong advocate of Taiwanese sovereignty, is despised by Beijing. In her New Year’s Day message this year, she told it to respect the Taiwanese people’s choice to live under a free, democratic system. On the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, she called on China to face up to what had happened and to become a democracy, and her government called on it to “sincerely repent” for the slaughter – in stark contrast to Ma, who at his meeting with Xi said that “[b]oth sides should respect each other’s values and way of life.” Over furious objections from Beijing, Tsai also recently visited the US in her official capacity as president. There, she said that Taiwan “would never be intimidated.” And, at a speech at Columbia University, she referenced the ongoing protests in Hong Kong, saying that “Hong Kong’s experience under ‘one country, two systems’ has shown…that authoritarianism and democracy cannot coexist.”

The DPP itself capitalizes on the backlash towards the mainland and mainlanders. When Taiwanese residents expressed anger at mainland tourists littering on the island’s beaches and defecating at their scenic attractions, the DPP drew parallels between this and the Nationalists’ behavior when they first arrived in Taiwan.

Of course, the lines between the Nationalist–supporting “mainlanders” who arrived in the 1940s and 50s and “local Taiwanese” have blurred a lot since 1949. Many “local Taiwanese” ended up joining the KMT, and it was one of them, Lee Teng-huei, who became vice president under Chiang Ching-kuo (Chiang Kai-shek’s son), and later president of Taiwan and, therefore, leader of the party when he died in 1988. It was Lee who instituted massive changes to the bifurcation of identity on the island. He introduced the word “new immigrants” or “new Taiwanese” to refer to the “mainlanders” (though this just infuriated them). He broadened the definition of what it meant to be “Taiwanese” such that it no longer referred to benshengren (or “native province person”) but to any citizen who called Taiwan home.

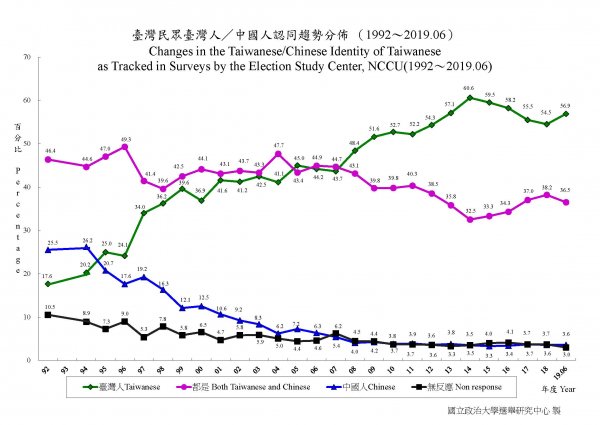

While first and second generation “mainlanders” felt relatively clear about their identities, later generations’ sense of self were much more complicated, with many aware of mixed parentage or choosing party affiliation according to political issues, like declaring independence, or economic issues, like closer ties with China, rather than family origin. Nowadays, only a few (usually older) people still call themselves “mainlanders” or even solely Chinese – the vast majority call themselves both Chinese and Taiwanese, or solely Taiwanese. Indeed, identifying as solely Taiwanese is becoming increasingly popular, especially amongst younger people.

Due in large part to this, the Nationalist Party has now muted its warmth for the CCP whilst vaunting the benefits of coupling the island’s economy with China’s. To identify as Taiwanese and support the Nationalist Party is no longer an outright conflict since one is arguably still acting in the best economic interests of Taiwan.

Whatever the case, the shifting sands of Taiwanese politics and the evolution of the Nationalist Party’s relationship with the CCP is an affirmation of William Clay’s observation that in politics “[t]here are no permanent enemies, and permanent friends, only permanent interests.”

Related posts: