Starving Watchdogs

By Manzoor Ali

Staff Writer

2/5/2019

Journalists in Peshawar sell tea to protest layoffs

Times have been lean for Saba Rani, a reporter based in Peshawar in Pakistan.

In early 2017, she was laid off from the Express Tribune, along with many of her other colleagues. In October 2018, she was abruptly sacked from Aaj News Television.

Her story is far from unusual. Rani is just one of hundreds of Pakistani journalists who have lost their jobs or seen their wages slashed in recent years. Pakistan’s news industry is facing a cash crunch that has led many outlets to downsize or even close. The Nawai Waqt group, one of the country’s oldest media groups, abruptly shuttered its Waqt News TV station in October 2018, laying off more than 170 employees. According to G. M. Jamali, president of a faction of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, an umbrella organization for journalists which split into two factions following an election dispute, some 850 journalists and 4,000 people in the media industry have been laid off in the past few months.

Pakistan’s economy has been slowing of late, but the news industry has been hit harder than most. Like the media industry in many other countries, the one in Pakistan is heavily dependent on ads for revenue. After peaking from 2016-17 at $621 million, however, total ad revenue has declined, falling by 6.9% to $578 million the following year, according to figures collected by Aurora Magazine, a publication that tracks advertising in Pakistan. This was despite the fact that 2018 was an election year, a time when political parties typically spend huge amounts on ads to reach voters. Like the media industry in many other countries, the one in Pakistan has done a poor job of transitioning to the digital age, suffering from the drop in print ad spending, losing out on digital ad spending to giants like Google and Facebook, and failing to develop other sources of revenue to make up for the shortfall.

Like the media industry in many other countries, the one in Pakistan has done a poor job of transitioning to the digital age.

Pakistan’s media also draws a comparatively small, but significant, amount of revenue from ads from government departments (typically concerning vacancies, project tenders, and campaigns) – from 2013-17 this averaged $26.5 million annually. This is at odds with the adversarial relationship the press often has with Pakistan’s government, as well as its powerful military.

In 2007, when then dictator General Pervez Musharraf deposed the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, it was the media that rallied the people against him. The government blacked out media coverage and imposed a state of emergency in the country, but this failed, resulting in Musharraf’s ouster. In April 2014, Geo Television, the country’s largest private TV channel accused the powerful Inter-Services Intelligence’s chief of ordering the assassination of its leading anchorman, Hamid Mir. In 2016, the English language newspaper, Dawn, published a story detailing a National Security Council meeting in which the civilian leadership told the army to move decisively against militants to prevent Pakistan from becoming internationally isolated. The “Dawn Leaks,” as they came to be known, caused a national crisis, as the opposition party branded them as an attempt to weaken the army. When counter terrorism personnel dubbed some people terrorists and killed them in front of their young children in the Sahiwal area of Punjab province in January, it was the local media that showed that the family was on its way to a wedding, and had nothing to do with terrorism.

Indeed, Pakistan’s media has a long tradition of resistance to military dictatorship. All Pakistan’s military dictators clashed with the media, with Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who ruled as Pakistan’s president from 1978-88, even having journalists publicly flogged. Under him, editors used to leave blank spaces on newspaper pages to protest censorship.

In recent years, though, there have been signs of either government pressure on the press, or self-censorship by the management or owners of media companies to ingratiate themselves with the government. In April 2018, Mosharraf Zaidi, a prominent commentator, accused The News International of censorship. “For the first time in over a decade, @thenews_intl has refused to publish my column,” he tweeted, also posting the rejected column. “This unnecessary muzzling of debate is not healthy. Strong nations cultivate robust debate. Weak ones fear it. Pakistan is stronger than it is being allowed to be.” Shortly after, Najam Sethi, another prominent journalist, said his show on GEO News had been taken off the air, and that Jang, Pakistan’s biggest media group, had stopped printing his column. “But its [sic] not their fault,” he tweeted. “They have been muzzled.” In January, Cyril Almeida, the reporter responsible for the Dawn Leaks, and one of the country’s most popular commentators, suddenly ended his weekly column without explanation. Other prominent anchorpeople have also been taken off the air, and many columnists have claimed that newspapers have refused to publish their articles on topics deemed “sensitive” by the military.

Getting reliable and comprehensive information on this trend is difficult. Not a single media outlet has publicly disclosed the number of layoffs and pay cuts it’s made, and there seems to be an omerta amongst media companies keeping them from talking about each other. The media companies themselves are owned by powerful and secretive families or media barons – the Jang group by the Rehmans, the Express group by the Lakhanis, the Nawai Waqt group by the Nizamis, Dunya News by Mian Amer Mahmood – who seem to make it their policy never to disclose what they’re doing, nor to report what’s happening to the others in the industry. Iqbal Khattak, Pakistani representative of Reporters Without Borders and executive director of Freedom Network, a Pakistani civil society organization, says the failure of these families and media barons to reinvest the past earnings from these businesses has hampered the ability of the industry to absorb the recent financial shock.

Khattak also says that the poverty of the country as a whole also means that only a fraction of the population is capable of helping to sustain the press. “40% of the country is on the verge of [the] poverty line, while 40% is below this line, and you have only 20% to look towards to sustain yourself,” he says.

“40% of the country is on the verge of [the] poverty line, while 40% is below this line, and you have only 20% to look towards to sustain yourself.”

Under Imran Khan, Pakistan’s new prime minister, who was elected in August 2018, things are likely to only get harder. His Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party is even more hostile to the free press than its predecessor, and was suspicious of the media even before it came into power. As an opposition party, it accused the former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, currently incarcerated on corruption charges, of throwing state money at media barons, and boycotted Pakistan’s largest media conglomerate, the Jang group, for about nine months because of what it said was biased reporting. It was Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf which cheer-led the campaign against the Dawn Leaks.

Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party is even more hostile to the free press than its predecessor

Now that it controls the government, Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf has tightened advertising spending to the media. It has refused to pay the $57 million the government owes various media outlets in advertising fees. In January, the cabinet also approved legislation to merge the Press Council (which regulates print media) and the Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (which regulates online media), into the Media Regulatory Authority, a move journalists have opposed, saying the government will use this authority to further curtail media freedom.

Dr Faizullah Jan, a journalism professor at the University of Peshawar, sees all this as a move by the state apparatus to control the media. This, Jan says, will hinder the media’s ability to scrutinize or criticize government activities.

“Whatever is the reason [behind] this crisis plaguing the media industry its ultimate beneficiary is [the] Pakistani government,” Khattak agrees. “This crisis is [a] calculated move [to] cripple [the] media industry.

“Whatever is the reason [behind] this crisis plaguing the media industry its ultimate beneficiary is [the] Pakistani government.”

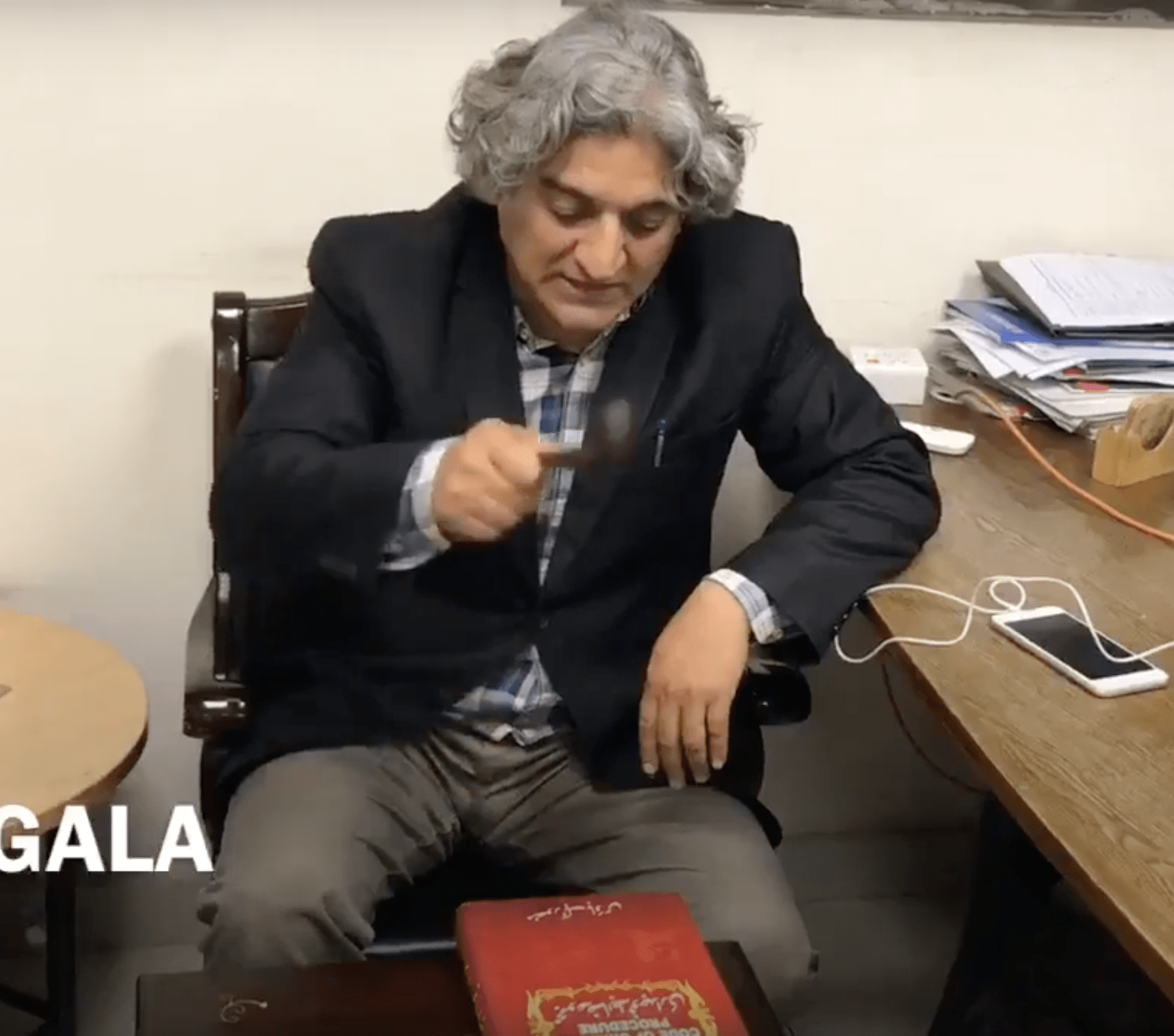

With no light at the end of the tunnel for journalists, many of them are experimenting with side businesses to make ends meet. Some are turning to social media to keep their journalism alive. One of these journalists, Matiullah Jan, together with several colleagues, has started a YouTube channel called Funny Gala (a play on the name of Imran Khan’s private residence, Bani Gala), where he lampoons the executive, the military, and the Supreme Court.

In one of the recent videos, Jan and his colleagues mock a recent decision by the Supreme Court to legalize the occupation of several thousand acres of land in Karachi by the country’s largest real estate developer, Bahria Town, in exchange for the developer paying the government the massive sum of Rs 460 billion ($3.2 billion).

Jan plays auctioneer and hammers the Pakistani Penal Code book

The video shows Jan playing auctioneer between several bidders, who are supposed to be real estate developers. As Jan hammers the Pakistani Penal Code book lying in front of him stating “Order, order!” the bidding reaches the sum of Rs 420 billion (420 is also the section in the Penal Code that deals with cheating and dishonesty). However, Jan declares that the amount will be Rs 460 billion and tells the successful bidder that the land now belongs to him.

“Aaj Insaf ki boli bala howi hai!” (“Justice has been auctioned at a high rate!”) declares one of bidders, a play on the Urdu idiom “Insaf ka bolbala” meaning “Justice has been done.”