The Controversial Legacy of Charlie Chan

By B. Alexandra Szerlip

Contributor

1/6/2020

Charlie Chan (left, played by Warner Oland) with Number One Son Lee (played by Keye Luke)

For much of the 20th century, Charlie Chan was one of the most famous detectives in the world, on par with Sherlock Holmes. Distinguished by his wispy mustache, three-piece suits, Panama hat and, most notably, his often witty, pseudo-Confucian aphorisms (“Bad alibi like dead fish – cannot stand test of time,” “Love is as unexpected as squirt from aggressive grapefruit”), Chan specialized in solving murders in cities around the world. Colorful settings – a racetrack, a swanky night club, a wax museum, a high-end casino, an archeological site – populated with appropriately colorful characters, added to his allure.

Charlie Chan was the invention of Earl Derr Biggers, a small-town Ohio “rube” who managed to matriculate to Harvard, then worked as a newspaper columnist and night police reporter before trying his hand at mystery novels. Intended as a minor character —“a mere bit of local color,” as Biggers later put it — Sergeant Chan grew in importance as the novels evolved.

No one, least of all his creator, could have anticipated Chan’s popularity, especially at a time when anti-“heathen Chinese” sentiment in the US was raging. Between 1925 and 1949, Hollywood cranked out 47 Chan adventures — some 52 hours of screen time. By the 1930s, the witty sleuth was practically a household name, a media star embraced as the first positive Chinese role model.

The film series, which disseminated Chan’s fame far beyond the six novels it was based on, included some masterful cinematography, anticipating the best of Film Noir, along with a cast of supporting actors en route to major film careers — Ray Milland (as a romantic lead), William Holden (lawyer and suspect), J. Carroll Nash (snake charmer), Leo G. Carroll (small-time black marketeer), newly-minted Dracula Bela Lugosi (suspicious fortune teller), and future Superman George Reeves (suspicious cruise ship passenger).

According to The Chinese Mirror: A Journal of Chinese Film History, Chan’s exploits were the most popular movies in 1930s China, as well as among Chinese expatriates. Far from feeling offended, native Chinese audiences “got” that Chan’s pseudo-Confucian proverbs were often used to comic, even ironic, effect. The New York Herald Tribune described Chan as “philosophical,” and “one of the most endearing and likable characters of the cinema.”

Far from feeling offended, native Chinese audiences “got” that Chan’s pseudo-Confucian proverbs were often used to comic, even ironic, effect.

Part of Chan’s appeal was that he was the opposite of Fu Manchu — a kind of Sino-Dracula fond of kidnapping innocent young white girls, plying them with opium and forcing them into sexual depravity – a fictional villain who played a significant role in spreading an already rampant “Yellow Peril” racism throughout the Western world. Though more unlikely a hero than his pipe-smoking English counterpart, Chan was as 20th century “American,” in his own way, as Holmes was Victorian British. China would never have produced him.

Today, though, Chan is often vilified for embodying the racist attitudes he, in fact, helped mollify — targeted as an indefensible and insidious stereotype, with his fractured English, fortune-cookie wisdom (long before “Chinese” fortune cookies became popular in the States), and seemingly servile manner, an Uncle Tom as pernicious in his appeal as Aunt Jemima.

An exemplar of what critic Stanley Crouch called “cultural miscegenation,” Chan continues to both delight and offend millions — in part because all but the first three Chan films (lackluster “silents”) starred white actors in the title role. His story offers a unique window into both American cultural history and the curiously contradictory manifestations of xenophobia.

***

Warner Oland — a Swede with Russian blood — was already a distinguished stage actor before appearing on film as an Italian gangster, a handful of “Oriental” villains, and as a Hasidic cantor, Al Jolson’s father, in The Jazz Singer. In 1931, fresh from two leading roles for Paramount as the satanic Fu Manchu, he was hired by Fox Films to star in a movie version of Biggers’ Charlie Chan Carries On.

Oland’s interpretation proved a great success with the public. One of his greatest fans was his co-star. “I couldn’t believe he was Swedish,” recalled Keye Luke, the Chinese-born actor who had an ongoing role as Charlie’s lanky, Americanized, Number One Son. “The man was what you would call an aristocrat among actors. He had a grand style. He lectured at Harvard, was the first man to translate Strindberg into English. In all of his Chan pictures, the Chinese he spoke he learned. He and I used to practice Chinese calligraphy…He made periodic trips to China…the man was a thoroughly dedicated artist…That’s why he was so good.” As for accusations of singsong fractured English, Luke pointed out that Oland “had the genius” to realize that Chan was speaking in his second language and to perform accordingly. Over the next six years – with a brief return to Oriental villainy as Dr Yogami in Werewolf in London – Oland would appear in 16 Chan adventures.

Number One Son Lee (played by Keye Luke) and Charlie Chan (played by Warner Oland)

The tradition of “yellow face” – white actors playing Asians on film – dates back to the earliest silents. A few portrayals were positive, others toxic, even incendiary. Mary Pickford as the doomed geisha, Madame Butterfly, in 1915. Rudolph Valentino as The Sheik (1921) promoting the idea of Arabs as savage beasts who auction off their own women. American Paul Muni and Austrian Luise Rainer (Academy Award for best actress) as struggling Chinese farmers in The Good Earth (1937). (At the height of her career, the stunning Anna May Wong – a longtime friend of Warner Oland – was considered for the female lead but rejected as being “too Asian.”) Katherine Hepburn as Jade in Dragon Seed (1944). Yul Brynner, the quintessential Siamese potentate, appeared 4,625 times in various stage productions and revivals of The King and I, in addition to the blockbuster 1957 film. 17-year-old Rita Hayworth played an Egyptian in a 1935 Charlie Chan feature. Quintessential American he-man John Wayne played Genghis Khan in The Conqueror (1956), and Marlon Brando turned Okinawan in Teahouse of the August Moon that same year.

Topping the list of “most controversial” is Mickey Rooney as the myopic, bucktoothed, bumbling Japanese landlord in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) – a role he was hired to “play overboard.” Public umbrage didn’t really manifest until decades after its release.

Ultimately adding to the future Chan series controversy were three “Negro” actors, all designated to play minstrel-inspired stereotypes in the name of comedy. The oddly named Mantan Moreland appeared as Birmingham Brown, Chan’s skittish, superstitious chauffeur with bulging eyes who was forever warning his boss to stay away from haunted mansions, die-hard Nazis, seances, and secret passageways. The studios considered Moreland enough of a draw (to Harlem audiences, among others) to include him in 14 Chan films, even giving him top billing.

Stepin Fetchit (né Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry), the first African-American actor millionaire, had a one-time stint as Chan’s manservant, Snowshoes – a lazy, slow-witted, jive-talkin’ “coon,”a character so excessively clichéd that at least one respected film historian calls the role “subversively anti-stereotypical.” All of Charlie Chan in Egypt, in which “Effendi Snowshoes” appears, pits black, yellow and Arab men against white Europeans, the former all concerned with truth and justice, the latter, obsessed with material wealth, all guilty of murder, larceny, and betrayal.

Asians were allowed minor roles – as members of Charlie’s “multitudinous” family (a dozen Americanized daughters and sons who say things like “Baloney!” “That’s a lot of applesauce!” and “Gee, is he dead, Pop?”), his wife, and a savvy Chinese circus contortionist (a love interest for Number One Son Lee).

***

Any detective story worth its salt depends on at least some scientific method.

The Chinese, it turns out, made a few significant forensic advancements long before anyone else. Hsi Duan Yu (The Washing Away of Wrongs), written in 1248, describes how to distinguish a drowned victim from a strangled one — the first recorded application of medical knowledge to crime solving.

Sherlock Holmes, who perhaps more than anyone (actual or invented) introduced the public to the importance of scientific crime fighting, was based on a real person, Scottish surgeon Dr Joseph Bell. (Giving credit where it’s due, Sherlock’s creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, was also quick to acknowledge the influence of Edgar Allan Poe, creator of the brilliant, eccentric C. Auguste Dupin, circa 1841. “Where was the detective story,” Doyle asked, “until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?”)

The 1800s, Holmes’ era, was an exciting time for forensic breakthroughs, many of which were incorporated into the sleuth’s repertoire: serology, ciphers, footprints, fingerprints, post-mortem bruising, the first use of toxicology (arsenic detection in a murder trial), handwriting analysis, photography (“Facts, like photographic film, must be exposed before developing” — Charlie Chan), the first microscope with a comparison bridge. Those tools, combined with deductive logic and acute attention to seemingly banal, mundane detail, are what set Sherlock apart. Policemen in Victorian England were more likely to rely on eyewitness accounts, and/or round up likely suspects and beat confessions out of them. 1888, the year in which several Sherlock cases are set, was also the year British doctors were allowed to examine Jack the Ripper’s victims for wound patterns.

Detective fiction built public confidence that police work could be founded on systemic methods and, by extension, that some sense (and order) could be made of the chaos, irrationality, and mass violence particularly endemic to large cities in the wake of the industrial revolution, soon followed by two horrific world wars. Fictional or no, Holmes and Chan suggested that a “new” and much needed kind of intelligence was at work. Early forensic scientists actually instructed their students to read Holmes and Chan stories as part of their studies.

Chan, too, had a real life model, Chang Apana, a diminutive Honolulu policeman who specialized in bringing opium smugglers and gamblers to justice, sometimes literally leaping over roofs in pursuit. Famous in his own right, despite the endemic racism of colonial Hawaii, Apana was known for carrying a coiled leather bullwhip around his waist, in lieu of a firearm. His resume included a robbery solved on the basis of a single silk thread and a murder solved by shoe mud traced back to a certain part of town. With the publication of Biggers’ first novel, Hawaiians were quick to recognize their local hero as a model. (In 2005, Apana would be named one of the 100 most influential people in Hawaii’s history, his bullwhip on permanent display in Honolulu’s Police Department Museum.)

Chang Apana, the real-life Charlie Chan

By the time Charlie Chan arrived, universities were beginning to offer degrees in criminology and “police science” for the first time. Microscopes were being used to compare bullet casings, blood techniques (including the use of luminol, which glows in the presence of even trace amounts of hemoglobin) were being developed, voiceprints studied. Though Chan books and films weren’t as forensically focused as Holmes, they gave at least passing nods to gunpowder stains, irregularities in typewritten letters, coded radiograms, and fingerprints, both real and forged. (Scotland Yard had introduced fingerprint matching to US law officials at the 1904 St Louis Worlds’ Fair.) An x-ray machine helps Chan locate a murdered archeologist hidden in a sarcophagus. In the course of solving the murder of a horse owner, allegedly kicked to death by his prize stallion, Chan makes particular use of blood spatter patterns. “Murder without blood stains,” he observes, “like Amos without Andy” – reference to a popular radio sit-com, set in Harlem, created by and starring two Caucasians in black face.

In other instances, chemical labs help Chan determine that an “invisible” bullet had been fashioned from frozen blood; that traces of “minasterol” (a drug that makes people lose all resistance to hypnotic suggestion) were present; that poisoned pygmy darts or cobra venom had been put to sinister use. Poison gas was a favorite weapon; in one case, it was hidden inside a violin in a phial designed to break at the pitch of a certain note, thus dispatching the musician.

***

Charlie Chan at the Opera (1936), Charlie Chan at the Olympics (1937), and Charlie Chan at Treasure Island (1939), all but the last starring Warner Oland, are among the best of the entire three-decade series, thanks to a combination of great set design, lighting and directing, colorful characters, and clever, well-constructed story lines.

Part whodunit, part horror flick, Opera featured a handsome Boris Karloff, already a major star, as a flamboyantly deranged former opera singer, initially confined to an asylum. Like Oland, he’d previously headlined as Charlie Chan’s opposite, in the embarrassingly awful The Mask of Fu Manchu (“Conquer and breed! Kill the white man! And take his women!”) and had just begun a six-picture series as Chinese detective Mr Wong (a Chan spinoff). Chan untangles the murder plot, beating his Caucasian colleagues (as usual) to the punch. “You’re all right,” dim, racist, Sergeant Kelley concedes. “Just like chop suey – a mystery, but a swell dish.”

Karloff (left) and Oland (right) in Charlie Chan at the Opera

The lower budget but very topical Olympics holds its own. The theft of a remote-control “auto-fly” device by a German spy ring is augmented with masterfully integrated newsreel footage of a China Clipper and the doomed Hindenberg (both of which Chan travels on), as well as of the recent 1936 Berlin Olympics (with all swastikas blotted out).

Treasure Island, too, made use of newsreel footage, this time from the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. The villain turns out to be Doctor Zodiac, a phony psychic and master of disguise (played by Cesar Romero) who, Chan deduces, suffers from “a disease known to science as pseudo-logia-fantastica,” a dangerous mix of fantasy, vanity, and ambition.

The killer’s modus operandi (ciphers and cryptograms, threatening letters sent to the media) eerily parallel the actual Zodiac killings that would terrorize northern California in the late 1960s and early 70s. While the real-life Zodiac Killer was never caught (DNA profiling had yet to be discovered), several historians are convinced he studied the film and was inspired by it. As the prescient Chan had surmised, “Possible truth disguised as fiction.”

***

In 1932 (and later in 1940), the Chinese government managed to block production of several Hollywood Fu Manchu films. But in March 1936, when “Mr Chan” first traveled to Shanghai, he was mobbed by journalists and photographers, lauded as a hero for bringing the first “positive” Chinese character to American film — “the smartest guy in the room,” the one who always managed to solve the crime, showing up his dimwitted, cigar-chewing white counterparts in the process. Screenings in Shanghai’s International Settlement cinemas were packed. Even Lu Xun (a.k.a. Zhou Shuren), the great Chinese writer known for razor-sharp, often bitter essays, was a huge fan.

China’s nascent film industry soon released the first of a half dozen Chan films of its own (a daughter, rather than a son, helps him solve crimes). Contemporary accounts noted that lead actor Xu Xinyuan carefully copied Oland’s mannerisms and speech — a Chinese imitating a Swede imitating a Chinese. At the same time, all six of Biggers’ novels were translated into Chinese by Xiaoquing Cheng, a celebrated detective novelist in his own right.

Lead actor Xu Xinyuan carefully copied Oland’s mannerisms and speech — a Chinese imitating a Swede imitating a Chinese.

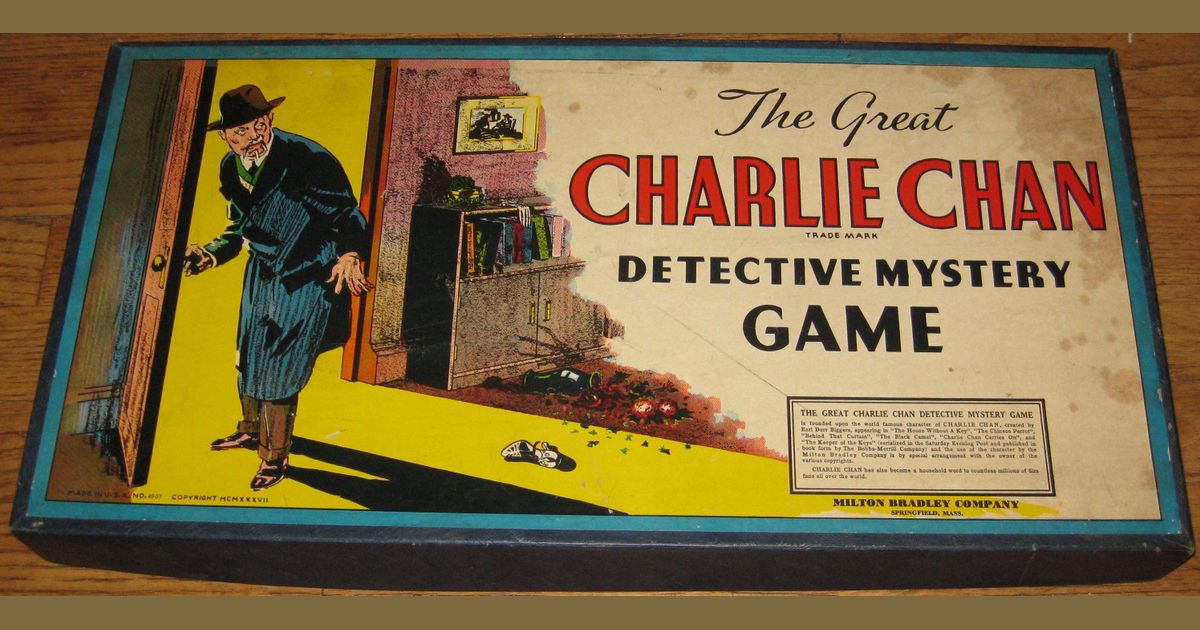

There were also three Spanish-language Chan films, a syndicated Charlie Chan comic strip, a Chan card game, and a Chan Mystery Board Game (precursor to Milton Bradley’s Clue), followed by several long-running radio shows.

***

Unlike the virtuously sober detective he made famous (Chan only drank sarsaparilla, a “soft drink” similar to root beer), Warner Oland had a serious drinking problem, though it was common knowledge among his fellow actors that a few nips prior to shooting a scene helped slow down his speech, to the character’s benefit. In 1937, the same year Oland’s wife sued for divorce, Oland walked off the set of Charlie Chan at the Ringside and simply vanished. He died the following summer, of bronchial pneumonia, exacerbated by alcoholism, in his mother’s bed — seven years before penicillin became available to the general public — having returned to his native Stockholm for the first time in decades. He was 58. What could be salvaged from the Ringside footage was incorporated into the newly minted Mr Moto series, yet another attempt to cash in on Chan’s popularity, but with a drinking and smoking “Japanese” detective, played by Peter Lorre.

There was no question that the Chan films, each shot in a matter of weeks for $250,000 and each grossing in excess of a million dollars – in the middle of the Depression, no less – would continue. Oland was replaced with Missourian Sidney Toler (22 Chan films), who was in turn replaced by Scotsman Roland Winters (6 films). With Oland’s passing, Keye Luke, who’d played opposite the Swede eight times, voluntarily left the series. (He went on to play Kato in the original Green Hornet series, worked on Broadway in Flower Drum Song, and played Master Po in King Fu opposite Kwai Chang Caine, a head-shaved David Carradine.) “I felt that they’d never be able to get another Chan like Oland,” Luke said, “and they never did.” Toler and Winters were, he allowed, “good, competent actors, but they were never Oland — not the complete Chan.”

***

Ultimately, Charlie Chan did more than entertain. Like Sherlock Holmes, he inspired generations of forensic scientists and professors; in Chan’s case, many were Chinese Americans who, it’s fair to say, would otherwise have been far less likely to embrace that particular path. Master crime writer Ellery Queen called Biggers’ creation “a service to humanity and to interracial relations.” And for what it’s worth, his character also made newsreels designed to reverse the nationwide prohibition against showing films on Sunday: “Humble self see much puzzlement why men can’t see Charlie Chan on Sunday when same men can play golf.”

That said, in the decades following the series’ end, Chan’s lovable Chinaman morphed with evil Fu Manchu in the public’s mind. The “underworld” alleys of Chinatown were a staple in Film Noir, which segued to Cold War Red-scare paranoia — implicit in The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Roman Polanski’s neo-noir Chinatown (1974), with its iconic closing line, and The China Syndrome (1979), among other box office successes.

In 1997, charismatic actor Russell Wong signed on to star in a Stephen Soderberg film as Charlie Chan’s grandson — a slimmed down, sexy, cerebral martial arts master with a love interest. Though some Asian-Americans were curious, if skeptical, others were outraged. (“If you put a black man in a hood, does that make the Ku Klux Klan a civil rights organization?” argued Filipino playwright Frank Chin.) The project was eventually cancelled.

Russell Wong, the Charlie Chan who never was (Picture Credit: Gordon Vasquez)

In 2003, a season of 23 restored Charlie Chan films from the 1930s and 40s was pulled from the Fox Movie Channel following a storm of protest over its depiction of Asians and African-Americans. The station insisted that the aim of the season was to accentuate “complex stories, interesting characters and Charlie Chan’s great intellect.” The Asian Law Alliance disagreed. “The movies were racist in the 1930s,” said Alliance director Richard Konda, “and they are still racist in 2003.”

The reputations of the black actors who’d appeared in the early Chan films, all suffered with the advent of the civil rights movement for having done the best they could have done with the limited roles — once thought hilarious, later demeaning and offensive — available to them at the time. Hindsight criticism of white actors who’d taken on non-white roles tended to focus on the studios rather than the actors.

***

Meanwhile, Hollywood’s “yellow face” tradition carried on. Neither the aforementioned David Carradine (Kwai Chang Kaine in Kung Fu (1972); Peters Sellers (Chinese detective Sidney Wang in Neil Simon’s Murder by Death, 1976); Peter Ustinov (the lead in Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen, a 1981 slapstick remake); Johnny Depp (as a Native American in The Lone Ranger (2013); nor Tilda Swinton (as The Ancient One in Doctor Strange (2016) raised as much ire.

A casting controversy did, however, erupt when Miss Saigon, a Vietnam-era retelling of Madame Butterfly, opened on Broadway in 1991, following a hugely successful London run (in which two white actors were cast as Asians/Eurasians, complete with eye prostheses and bronzing cream).

Still, when Hollywood finally allowed itself an all-Asian cast, in 1993’s Joy Luck Club, then a quarter of a century later in the romantic comedy Crazy Rich Asians, a number of Asian-Americans voiced their displeasure. As one critic noted, “An environment where only one person, or portrayal, is permitted to stand in for the whole is bound to turn into a breeding ground for resentment.”

Charlie Chan Is Dead also appeared in 1993, a literary anthology featuring largely young, under-the-radar Asian-American talents hailing from Korea, Cambodia, the Philippines, Pakistan, and beyond. Its introduction referenced Little Black Sambo, Tonto (The Lone Ranger’s “Indian” sidekick), Amos n’ Andy, Fu Manchu, Aunt Jemima, and the relentless “colonization of our imagination” by both Hollywood and the Western literary canon. An updated edition (subtitled: At Home in the World) appeared in 2004, a top-hatted, cocktail-sipping Anna May Wong audaciously peering out, challenging the reader to enter, from its cover.

Sherlock Holmes, never subject to racial (or British class) prejudice, has enjoyed a kinder and far less volatile fate, portrayed in some 200 films by at least 44 different actors and, most recently, in a trio of witty, fast-paced, updated-for-the-21st century series starring Benedict Cumberbatch, Robert Downey Jr, and Johnny Lee Miller (with Asian actress Lucy Liu as Watson) as the great detective.

***

Racism is an ever-evolving construct.

The Chan films reflected, and played off of, the zeitgeist of their era – the good, the bad, and the ugly. Charlie Chan, for his part, was strongly anti-Japanese. Many Shanghai-based Chan fans in the 1930s, 40s, and beyond were likely also fans of Darkie Toothpaste, a hugely popular East Asian brand with a grinning, minstrel-inspired logo and a Chinese name that translated as “Black People Toothpaste.” It wasn’t until 1989, in response to public pressure, that the name was changed to Darlie, the logo “lightened” into a racially ambiguous man.

Chan “might have been a stereotype,” observed New York Times movie critic Dave Kehr, but he was “on the side of the angels.” And, he added, “one of the few heroic figures in American film to function proudly as an intellectual.”

Charlie Chan “might have been a stereotype,” observed New York Times movie critic Dave Kehr, but he was “on the side of the angels.”

Today, 75 years after the last film in the series was released, the Chinese detective’s oeuvre continues to be periodically “re-discovered” by audiences, thanks to home video sets (Fox Movie Channel reversed itself and issued a collection in 2006), DVD archive reissues from MGM, Warner Brothers, Turner Classics, and YouTube. Some viewers are uncomfortable or offended, others manage to see the films as Chinese co-star Keye Luke did.

“Demeaning to the race? My God! You’ve got a Chinese hero!” he said. “We thought we were making the best damn murder mysteries in Hollywood at the time. We were very proud of them.”

“Sometimes,” Oland’s Chan might have added, “jewel found in ashes.”