The Machine In The Ghost

By Felix Behr

Staff Writer

16/10/2019

Commander Antilles strides down the corridors of Princess Leia’s Tantive IV. He tells an accompanying soldier to secure the airlock and prepare the escape pods. The soldier bustles off and Antilles waits for a door to open in the slow sci-fi manner. As it does, the figure of Carrie Fisher, as she appeared in Star Wars: Episode IV, appears.

Here, the audience tenses. Almost 40 years have passed between Episode IV’s 1977 release and Rogue One’s premier and the image of Carrie Fisher looked almost unchanged. More importantly, Carrie Fisher had died the week before. And yet, there she was. Or at least, an obviously digital depiction of her was. So was Peter Cushing, the British actor who played Grand Moff Tarkin in the original movie, now dead for 22 years. CGI transcended death.

Responses came quick, with applause and unease both present. Catherine Shoard, film editor at The Guardian, wrote that despite the way “Grand Moff’s dialogue doesn’t seem entirely synchronized, and that’s an alarmingly waxy pallor” the “CGI resurrectors” did a good job. However, Eliana Dockterman, a staff writer for Time, felt uneasy before the younger Carrie Fisher: “There was something particularly plastic about this version of the young Carrie Fisher — so smooth and so perfect it couldn’t be real — that pulled me out of the moment.” Everywhere the question concerning the ethical nature of granting actors a certain immortality was raised.

Carrie Fisher in Rogue One

The gut reaction at the time was that something transgressive had occurred. And in a sense, it had. As technology continues to change the way we live, it’s also changing the way we live after death. A new kind of ghost has emerged from data-driven machines, crossing back into life.

A new kind of ghost has emerged from data-driven machines, crossing back into life.

We’re all familiar with the restless spirit trope: someone dies, but due to some tragedy (like a violent death) or unfinished business, the soul cannot pass on, leaving a specter behind. Certain events imprint that person’s psyche onto his surroundings, so that it continues to haunt them after death.

Nowadays though, we don’t need to die to imprint our surroundings — living works just as well. Each of us generates terabytes of data in our lifetimes through our online interactions. We upload countless photos and videos of ourselves. Everything, from our interests to our habits to our mannerisms to our images are imprinted onto the vast (and often commodified) global database and they linger long after we’re gone as digital echoes, shadows, ghosts.

Of these ghosts, Roman Mazurenko’s has received the most publicity. On November 28th, 2015, Mazurenko’s exploration of Moscow ended abruptly as he was hit by a speeding car. He was pronounced dead two days later.

As she grieved, Eugenia Kuyda, Mazurenko’s best friend and the founder of the bot-powered messaging app Luka, wondered what a version of her app would look like if it sounded like Mazurenko. She proceeded to collect as many of his text messages as possible from friends and family to feed a new chatbot. The result engaged in conversations that sounded like Mazurenko to Kuyda. The app, titled Roman Mazurenko, is still available for download.

The app seemed to touch on an untapped market. In an article for Quartz, Kuyda explained how “people started sending us emails asking to build a bot for them. Some people wanted to build a replica of themselves and some wanted to build a bot for a person they loved and that was gone.” The new bot, Replika, feeds off hours of conversation between the user and the app until it has gathered enough information to consistently mimic the style and the personality of the writing it has been consuming. After many, many sessions a replica of you can function as its own conversationalist. A similar startup called Eternime promises to preserve your thoughts, stories, and memories for eternity as living biography.

The difference between asking the mechanically rendered Mazurenko about his drunken weekend and seeing Fisher and Cushing act in Star Wars is due to the data from which they were summoned, or the way their existence has imprinted into data available to us. One learns to speak from the words of its corporal counterpart. The other is a projection recreated from recordings of Fisher and Cushing’s original roles. Both, though, create stand-ins from the impressions left by their lives. And both tend to produce a certain level of unease.

Digital ghosts unnerve us because they challenge the special position we’ve carved for humanity. The recreations of Fisher and Cushing fall directly into the Uncanny Valley, in which a product, usually a robot, looks human but not human enough. “[In the valley there] are robots that are unnerving for their human qualities, their similarities to us,” wrote the philosopher Timothy Morton in Being Ecological. “And there are corpses somewhere down there. And right at the bottom of the valley we have animated corpses, zombies. They are dead and disgusting and also disgustingly alive.” We don’t feel uncomfortable because something fails to copy humanity. Rather, the distaste is due to the presumption of lesser things to mimic it. The mimicking offends us because if a construct can pass off as a human, then maybe we’re not so special after all.

“[R]ight at the bottom of the valley we have animated corpses, zombies. They are dead and disgusting and also disgustingly alive.”

To reinforce the boundary between humans and human-like non-humans, we invent obstacles like the Turing Test. We sit in a room and commence two text conversations, one with an advanced chatbot and the other with an actual person. If after a series of questions and answers, we can’t tell which is which, the machine has supposedly passed. But really, the opposite is the case. It’s not that the machine has passed, but that the human has failed. The human has failed to prove himself as something more than a series of algorithms that a machine could replicate.

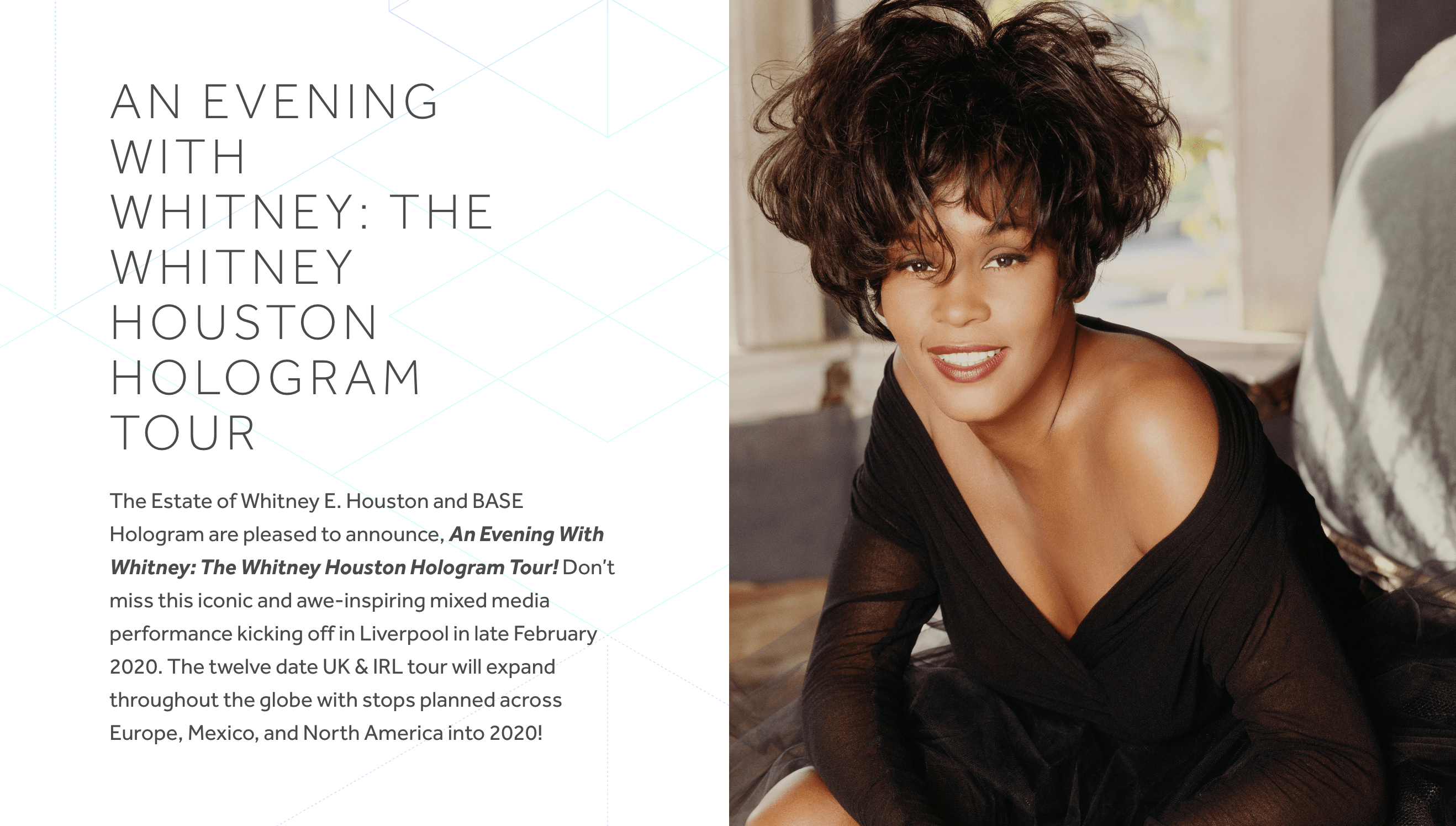

As this kind of preservation progresses, new laws concerning the posthumous ownership of such data will be needed. While services tend to only take data to improve themselves, it doesn’t take a particularly cynical person to question how future companies will treat issues of copyright with respect to the individual. Just look at James Dean. In 2014, CMG Worldwide, an intellectual property management firm, sued Twitter to reveal the identity behind a James Dean account, claiming that the account infringed on federal trademark laws and Indiana’s rights of publicity, which awards 100 years of protection for publicity rights. CMG Worldwide owns the images and the quotations that belong to the brand “James Dean.” While James Dean died long before the technology to digitally capture his trace or echo arrived, other celebrities didn’t. Although she died in 2012, Whitney Huston, an American singer, is scheduled to tour Mexico, Europe, and the US via hologram in 2020.

“I Will Always Love You”

In the midst of our worries over the probable automation of our jobs, we’ve ignored the creep towards automating human functions. Nothing so grand as “The Great Replacement” or a Terminator-styled revolution lie in wait. Rather, our ghostly doubles will come into being in more banal ways. In China, a software engineer called Li Kaixiang made the news when his girlfriend discovered that the person who was texting her was actually a chatbot programmed by Li to keep up with her messages as he worked, sending sweet nothings like “Baby, this is our 618th day together. Hope you’ll feel bright as the sun.” As with our ghost, what makes us us is unerringly copied.

I left Rogue One, however, without tendrils of anxiety over existential automation tearing at me — I’m not that pretentious. Rather, my thoughts whirled around the fact that I had just watched actors play the same role in a prequel to a film made almost 40 years ago. And it sort of worked. Around me, people took pictures, sent texts, adding to the data troves of their lives. Without thinking, I pulled out my phone and texted my partner, feeding my potential ghost: “Just saw Rogue One. It’s alright. Not as amazing as people say.” I wonder if she could have told the difference if that message was sent by a programmed replica of me instead.