The Man Who Trusted Too Much

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

29/7/2020

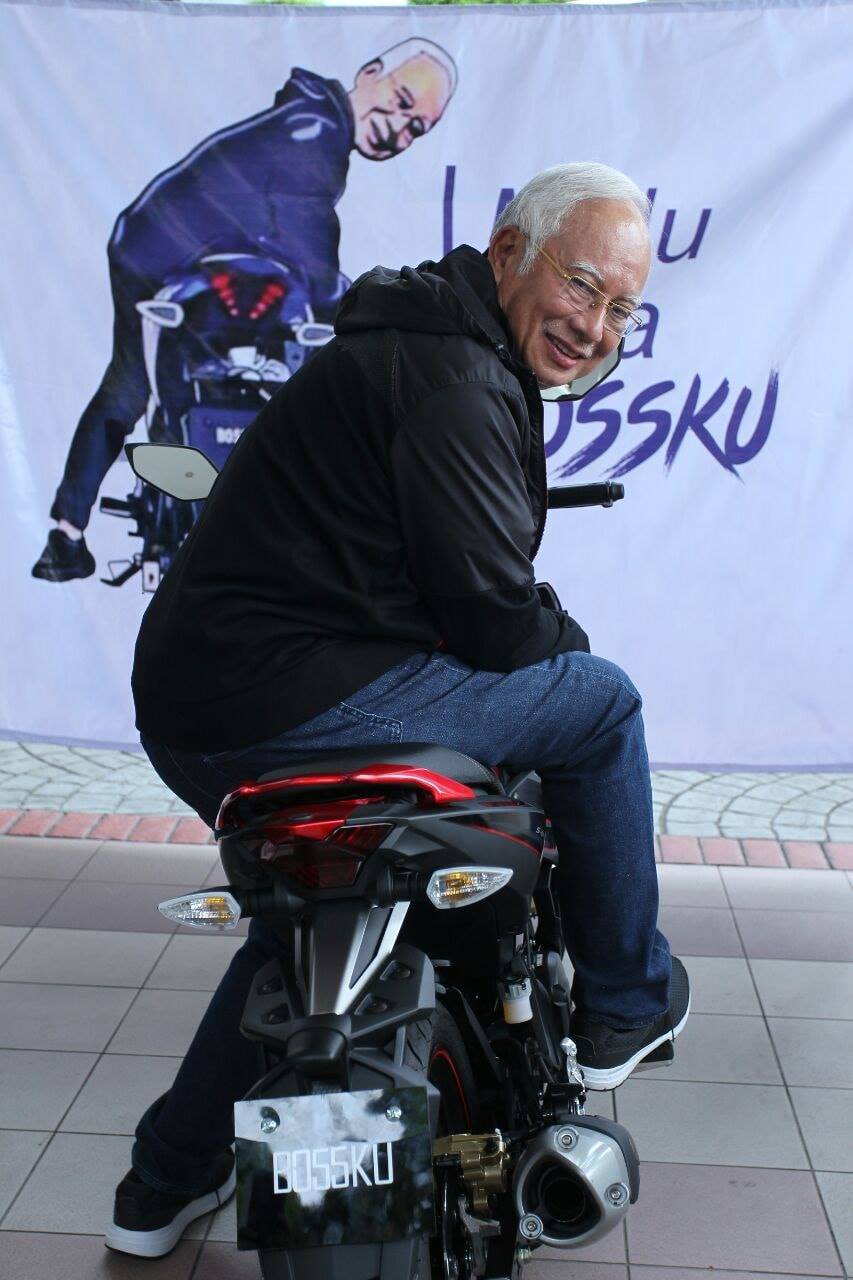

Former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak (Picture Credit: Budiey)

Yesterday, the Malaysian High Court found former Prime Minister Najib Razak guilty of all seven corruption counts laid against him in a case involving SRC (a former unit of a state investment fund). Some commentators are describing this as the fall of a political giant. Don’t believe that for a second: Najib is a giant nothing – he is an oaf, a political pygmy so painfully deficient in both intelligence and charisma that he’d likely never have achieved even middling rank were he not the son of one former prime minister and the nephew of another. He is good at virtually nothing; he is a living example of the dangers of nepotism.

There are some dictators to whom one must concede a kind of grudging admiration, a certain Mephistophelian dignity: Lee Kuan Yew, Vladimir Putin, Vlad the Impaler. Najib isn’t one of them. Look at his ridiculous face – he doesn’t even inspire fear. To the extent that people feared him at the height of his power, it was his office they feared – an office he largely inherited – not the soft, plump, petty tyrant occupying it. And he’s a coward too. As a reporter, I saw him flee the scene when someone asked him an uncomfortable question. In Blood and Silk: Power and Conflict in Modern Southeast Asia, journalist Michael Vatikiotis recounted flying with Najib in a helicopter to a political rally in a contested state. As they approached the site of the rally, Najib noted nervously that the crowd there seemed small, and wasn’t holding up banners of welcome. “Come on,” Vatikiotis said, “you’re a politician. Surely you aren’t worried about a bit of heckling?” In response, Vatikiotis wrote: “Najib looked at me with fear in his somewhat bulbous eyes and then ordered the helicopter to return to base.” Najib isn’t just a disgrace to national leaders in general; he’s also a disgrace to self-respecting dictators everywhere.

His rule as prime minister was what you’d expect from a craven bully: vindictive and paranoid, marked by chronic insecurity punctuated by periodic spasms of state violence. He persecuted political cartoonists for lampooning him. He persecuted news publications that revealed how he was robbing the country blind. He fired the attorney general because he was on the verge of filing corruption charges against him. He fired his deputy when even he spoke out against Najib’s blatant pillaging of a state fund. He purged his party of everyone except fellow crooks and sycophants. He had teenagers arrested and paraded in handcuffs on national news for insulting his likeness, for failing to show him respect, a respect he felt entitled to but repeatedly refused to earn. He disgraced this country by making it the epicenter of the world’s biggest corruption scandal.

Najib’s rule as prime minister was what you’d expect from a craven bully: vindictive and paranoid, marked by chronic insecurity punctuated by periodic spasms of state violence.

Trying to paper-over this train-wreck is a hilariously bad (yet extremely expensive) PR campaign, which plays like a gag reel of political buffoonery. Here’s Najib awkwardly taking selfies with other world leaders and constantly using the word “selfie” to try to appeal to the younger generation. Here’s Najib trying to capitalize on the popularity of Korean pop star PSY at an event, and getting mocked instead (Najib to crowd: “Are you ready for PSY?” Crowd: “YES!” Najib to crowd: “Are you ready for BN [Najib’s political coalition]?” Crowd: “NO!” *laughs at him*). Here’s Najib posing for a photo at a polling center but putting his ballot into the wrong box. Here’s Najib, dressed in a canvas jacket, jeans, and sneakers, posing awkwardly on a motorbike like he’s some mat rempit (Malay motorcycle hooligan). Here’s Najib awkwardly leading a cheesy singalong (Why is he so awkward?) with a group of young people, wherein they sing about (What else?) how he’s innocent of criminal charges. Here’s Najib sitting down for an interview with Al Jazeera and then trying to flee when the interviewer asks him about his corruption scandal and whining pitifully at her: “You are not being fair to me!”

Picture Credit: Najib’s Facebook page

To those of us happy to finally see this evil bastard apparently getting his comeuppance, it’s hard to resist a certain schadenfreude, though I’m proud to say that I kicked him when he was up. It’s also worth remembering that Najib will appeal his sentence to higher courts, that the independence of Malaysia’s judiciary and justice system is questionable (though Najib is also facing a battery of other, even more serious charges), that a coalition that he’s a part of rules the country, and that fortunes in Malaysia’s political landscape shift with the wind.

Whatever happens, though, it’s so rare us Malaysians get to see justice done that we should savor it when it comes, and those of us who believe in truth and integrity should be proud that we’ve gotten this far, that for one shining moment, at least, we managed to hold a former prime minister to account for his crimes, despite his feeble excuses and the best efforts of his slippery defense lawyer, Muhammad Shafee Abdullah.

It’s so rare us Malaysians get to see justice done that we should savor it when it comes.

In his attempt to get Najib’s sentence mitigated (he was eventually sentenced to 12 years in prison and fined $49 million), Shafee hilariously tried to portray his client as himself a victim of a scam masterminded by his co-conspirator Jho Low, saying that “If he was at fault, he was only at fault in trusting people that ought to run the company [the state investment fund].” (As a reporter in Netflix’s documentary series Dirty Money noted, in order to rely on this defense, “Najib has to paint himself as a drooling idiot who was hoodwinked by a twenty-something-year-old.”)

But in a sense, Shafee was right. Najib was too trusting. He trusted that the gravy train would never end, that his pyramid scheme would never come crashing down. He trusted that cash was king, that he could use the money he siphoned from the country to bribe or buy off enough people to keep himself in power. He trusted that the Malaysian people would believe his lies. He trusted in the primacy of politics, that the ruling coalition could completely control the courts, that there were no holdouts of professionalism and honor in the judiciary, like that exemplified by his judge, Mohd Nazlan Mohd Ghazali. It was this trust – in corruption, in patronage, in unbounded cynicism – that led to his downfall.