The Mob Enters the Newsroom

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

6/6/2020

Note: This piece has been updated to include new developments.

The latest erosion of institutional integrity in America was not the result of President Donald Trump’s authoritarian impulses, but a stunning own-goal by the New York Times.

On 3rd June, it published an op-ed by Republican Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas called “Send In the Troops,” in which Cotton urged Trump to mobilize the military to prevent crime in the wake of the unrest following the police killing of George Floyd. The publication of this piece triggered outrage amongst many Times readers and staffers, who said it should never have been published. Nikole Hannah-Jones, a correspondent for the New York Times Magazine tweeted that she was “ashamed” that the Times ran it, whilst other staffers claimed that “Running this puts Black @NYTimes staff in danger,” and 800 employees signed a letter protesting its publication.

Two days later the Times appended a cringing self-criticism to Cotton’s op-ed, saying that “the essay fell short of our standards and should not have been published.” It pointed to Cotton’s assertion that antifa had infiltrated protest marches as “unsubstantiated” and his assertion that police officers “bore the brunt of the violence” as “overstated.” It said that “the tone of the essay in places is needlessly harsh and falls short of the thoughtful approach that advances useful debate.”

Two days later the Times appended a cringing self-criticism to Cotton’s op-ed, saying that “the essay fell short of our standards and should not have been published.”

Jonathan Turley, a law professor at George Washington University, and a frequent author of op-eds himself, noted this with alarm, writing: “The attacks on the newspaper capture the rising intolerance for opposing views in our society.” He called it “chilling” that the demands for censoring Cotton’s op-ed “are coming from journalists and writers themselves. This is akin to priests campaigning against free exercise of religion…I never thought I would see the day where writers called for private censorship of views.”

I suppose we should be thankful that the Times wasn’t craven enough to remove Cotton’s op-ed entirely, but that’s still pretty horrific. A fair reading of his piece will find those claims to be unfounded. First of all, it’s unclear how an op-ed arguing for Trump to mobilize the military to prevent crime related to the unrest would “put black NYTimes staff in danger” – are soldiers supposed to be more trigger-happy towards black people than the police or National Guardsmen? Second, whilst it’s unclear whether antifa members have infiltrated the protests marches, there’s nothing to suggest they haven’t, and, given that they usually take part in protests like this, it would actually be surprising if they sat this one out. Cotton’s assertion that police “bore the brunt of the violence” is debatable. Police are usually at the front lines of unrest, and so it’s reasonable to suppose that they shouldered most of the violence, though some may contend that it’s the protestors themselves who did. Cotton obviously thinks it’s the former, and an editor cannot substitute her own judgment for a writer’s; all she can and should do is make sure he makes a plausible case for it. And Cotton did: he backed up his assertion with reports of officers being shot whilst trying to prevent rioting and looting, as, I’m sure, the Times ensured he did.

What about the tone of the piece? I found it reasonable. It pointed out that 58% of registered voters said they’d support cities calling in the military to manage the unrest. It denounced the rioting and looting related to George Floyd’s killing, as well as what Cotton calls the “feckless politicians” who have failed to take action to prevent it. It is angry in its denunciations, yet who would not be angry about the opportunistic thieves who’ve used the protests as an excuse to loot luxury stores or mindlessly trash neighborhoods, or about the innocents who’ve been hurt by the violence, like those who depend on public amenities that were destroyed by rioters, or those whose shops and livelihoods were burned down just because they happened to be near a police station?

A destroyed store in Minneapolis after the riots related to George Floyd’s killing (Picture Credit: Jenny Salita)

Most importantly, the op-ed was careful to distinguish between violent rioters and looters (who are indeed criminals) and the majority of the protestors who are peaceful. It called for the military to be sent to stop the former, not the latter. It called for coercion to be applied to prevent rioting and looting, not people’s lawful exercise of their First Amendment rights. It pointed out that Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson deployed the military domestically too, to disperse mobs that prevented school desegregation or threatened property or innocent lives. This is a fair comparison, and Richard K. Betts, director of the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University made the same comparison in an interview in Foreign Policy. “As usual,” Betts concluded, “Trump’s rhetoric and actions are vile and alarming, and his desire to use the military is unnecessary as long as violence does not overwhelm police and the National Guard. But to rest opposition to the odious current president on the notion that using the military for law enforcement is impermissible would reject ample historical precedent, much of which has served justice more than Trumpian villainy.” In terms of overall quality, Cotton’s piece is actually of a higher standard than many op-eds in the New York Times, especially those written by writers on the left, which seem to be exempt from usual standards of quality control.

Other arguments given or suggested as rationale for the Times’ reversal were even more ridiculous. Three staffers said sources told them they’d no longer provide them with information because of the op-ed, even though any true journalist knows not to trade their independence for access. Dean Baquet, the Times’ executive editor said, ludicrously, that even “very sophisticated people” thought op-eds reflected the views of the publication as a whole, which, if taken to its logical conclusion, would be an argument for banning all op-eds from the paper, save the ones its editorial team agreed with, and thus having no opposing views whatsoever in its opinion section.

Other arguments given or suggested as rationale for the Times’ reversal were even more ridiculous.

As a matter of fact, I don’t agree with Cotton’s conclusion that Trump should use the Insurrection Act to mobilize the military to deal with the unrest, at least, not without state governors themselves requesting it – I view it as a last resort that has not (yet) become necessary. But I recognize the need for room for disagreement, and I benefitted from hearing his argument, even if I was not ultimately swayed by it. In his article in The Atlantic, “Against the Insurrection Act,” Conor Friedesdorf showed how to deal with an argument you disagree with. He acknowledged the points in favor of deploying troops to deal with the riots, including that some people might trust soldiers more than the police, and weighed them. Ultimately, however, he concluded it would be a bad idea for a variety of reasons, including that the military would be under the president’s direct control, and Trump can’t be trusted not to cock things up. There are some valid reasons in favor of Cotton’s argument. There are many valid reasons against it. There is no valid reason, however, to refuse to even hear his argument, let alone to prevent others from hearing it.

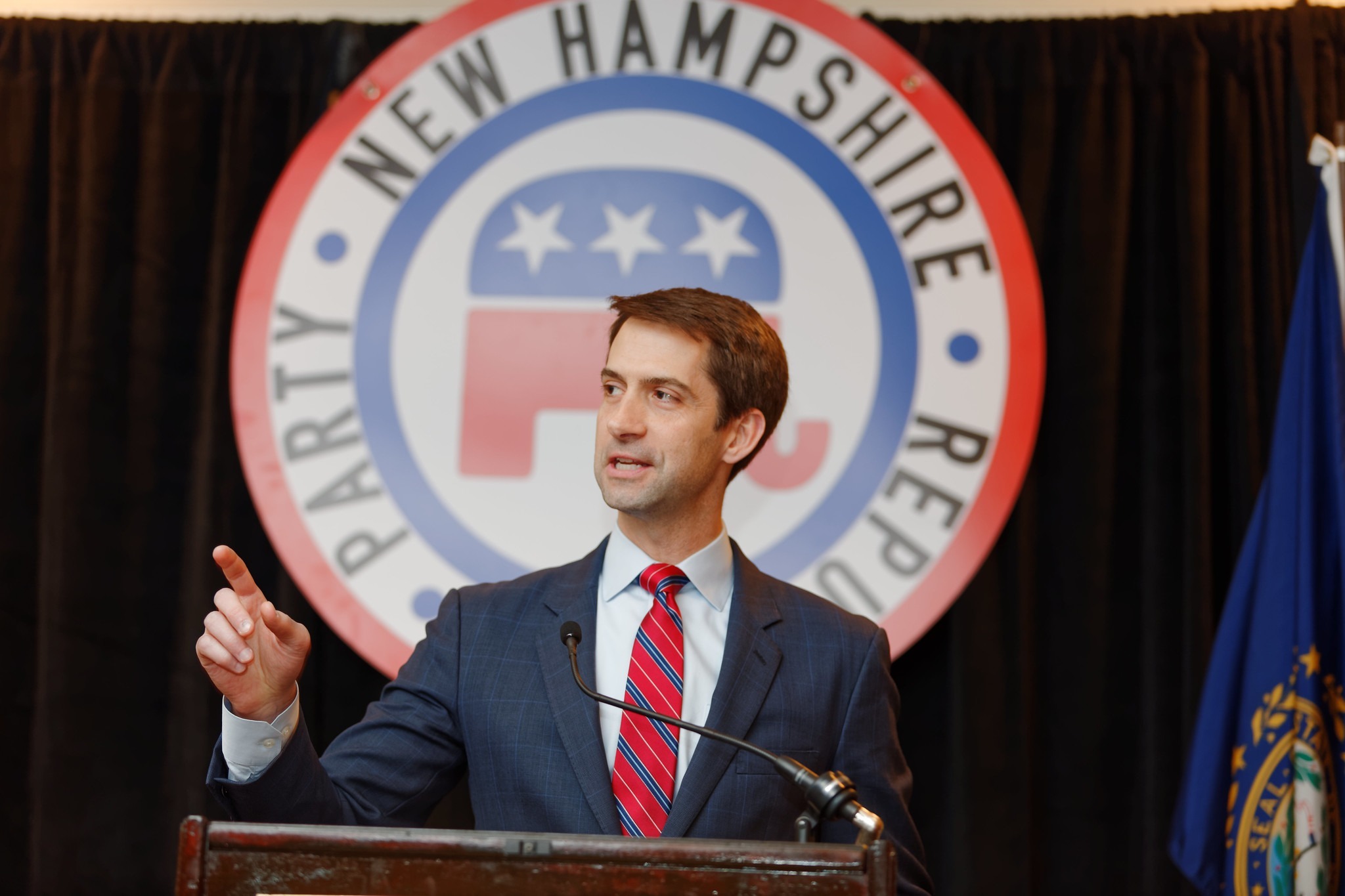

Tom Cotton (Picture Credit: Michael Vadon)

As a journalist, my writing has pissed off those on the right, those on the left, and, sometimes, both. I’ve had many editors, and the best ones, the ones I respected most, were those who held me to rigorous standards and published my articles – even though they might not have agreed with them – so long as I made a good case, and who then refused demands from irate readers to take them down or apologize for them. As an editor myself now, I’ve tried to follow their example, conscious of the need to hear different, even dissenting ideas, and that a publication that only airs one set of views would be a very dull one indeed.

I’d have thought the New York Times knew this. After all, it’s published op-eds even by America’s enemies, like Taliban leaders and Vladimir Putin (who used the opportunity to cast aspersions on the United States), without much fuss, on the grounds that they’re important enough that what they think matters, even if it’s repugnant. Ironically, it seems the Times is more charitable towards actual far-right foreign dictators than towards right-leaning American politicians. (In her article, “Tom Cotton’s Fascist Op-Ed,” Times columnist Michelle Goldberg tried to square this circle by arguing that that now is too sensitive a time to publish an op-ed like Cotton’s, since the issue it addresses is still playing out, and that, presumably, the timing was less sensitive when the Times published those other op-eds. This is complete nonsense, since news publications value the timeliness of stories immensely, and so are much keener to publish op-eds when they address a hot topic (i.e. when they’re more “sensitive”) rather than later when their relevance has become academic. “No, we shouldn’t run this op-ed on the protests when everyone’s talking about them. We should run it later when they’ve died down and fewer people care,” said no journalist, ever.)

Ironically, it seems the Times is more charitable towards actual far-right foreign dictators than towards right-leaning American politicians.

Why this disparity, then? Probably because of the tribalism, or perceived tribalism, of Times readers and staffers, who view the opinions of conservative politicians as beyond the pale, even if, apparently, those of Islamofascists and Russian autocrats are not. Another reason for the outrage over Cotton’s op-ed is tribalism’s equally ugly corollary – territoriality. After all, aren’t the pages of the New York Times supposed to be their safe space?

If the Times has allowed itself to become the exclusive safe space of the far left, though, it only has itself to blame. Its reversal on this issue is an insult to itself as well as its readers, and will play into the right-wing narrative that publications like it are just leftist echo chambers, intolerant of true diversity. A truly good publication recognizes the obligation to inform, guide, even challenge its readers, not pander to them.

For one shining moment, the Times seemed to remember that. “We published Cotton’s argument in part because we’ve committed to Times readers to provide a debate on important questions like this,” wrote editorial page editor James Bennet on 4th June, before the Times caved in to the pressure, decided its previous judgment and its editorial process was flawed, and reversed itself. “It would undermine the integrity and independence of the New York Times if we only published views that editors like me agreed with, and it would betray what I think of as our fundamental purpose – not to tell you what to think, but to help you think for yourself.”

Unfortunately, Bennet has since resigned from his position. In his place is Katie Kingsbury, who, in a note that sounds like it came from the Spanish Inquisition, promptly told Times opinion staff anyone who sees “any piece of Opinion journalism – including headlines or social posts or photos or you name it – that gives you the slightest pause, please call or text me immediately.”

Translation: If you detect any sign of heresy amongst your fellow journalists, immediately notify me or your closest Inquisitor.

I hope the Times rediscovers its journalistic principles. Already many authoritarians around the world watch gleefully as segments of American society self-destruct and forget their commitment to freedom, diversity, and tolerance. The last thing we need is for an institution as venerable as the New York Times to do the same.