The Myth of the Perfect Hero

By Erin McIntosh

Staff Writer

9/9/2020

Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze

In these times of upheaval — in the face of a pandemic, economic crisis, and nationwide riots – it’s tempting to look to heroes for guidance. But what makes a hero? Who we choose to call heroes is telling. Recently, George Floyd, the black man whose death at the hands of police sparked this summer’s sweeping Black Lives Matter protests, has gone from ex-convict to martyr, with some calling for a statue of him in the planned National Garden of American Heroes. Others have taken issue with his canonization, though. “What I find despicable is that everyone is pretending that this man lived a heroic life when he didn’t,” said political commentator Candace Owens, referencing Floyd’s long history of violence and criminality, including robbing a pregnant woman at gunpoint. Whilst saying that no one should have died like he did, she went on to declare: “I refuse to accept the narrative that this person is a martyr…That we should be buying t-shirts with his name on it.” She’s right. Making someone out to be a hero when that person obviously isn’t one is delusional and counterproductive.

When we expect heroes to be perfect, they inevitably fall, if only because they can’t live up to that ideal of perfection.

A common definition of the term “hero” is “a person noted for courageous acts or nobility of character.” The heroic pantheon often includes people like George Washington, who helped liberate America from the British Empire, Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, who won the Civil War and ended slavery in the United States, Winston Churchill, who defied Hitler and led Britain to victory in the Second World War, and Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s democracy icon, who won the 1990 election in a landslide and then stoically endured 15 years of house arrest because she refused to submit to the military junta that nullified the election results. Such figures are often idolized, and biopics are made celebrating their lives, peppered with inspiring speeches, all while glossing over the less salutary parts of their characters.

Under closer inspection, some of the sheen comes off. One writer assesses Washington to be both “one of America’s greatest heroes” and “a moral coward” for his refusal to free any of his hundreds of slaves before his death. It’s debatable to what extent Lincoln considered the Civil War to be about slavery. As he wrote in 1862: “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” Does it count for anything that he held that his “personal wish” (italics his) was “that all men every where could be free,” if he wasn’t actually fighting for it? Likewise, Grant, commanding general of the Union Army in the Civil War and, later, 18th President of the United States, was pro-abolition at a time when that sentiment was far from popular, at great risk to his reputation and career. But, at the same time, he ended the sovereign tribal treaty system, a decision that destroyed Native American rights and made them wards of the state. Churchill, a bulwark against tyranny, was also a known imperialist and racist. And the Nobel Peace Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi has gone from a champion of democracy and human rights to being an accomplice to and apologist for the suppression of free speech and the genocide against Rohingyas in Myanmar by the same military junta she spent so many years opposing. “She was a moral symbol,” Kenneth Roth observed in The New Yorker, “and we read into that symbol certain virtues, which turned out to be wrong.”

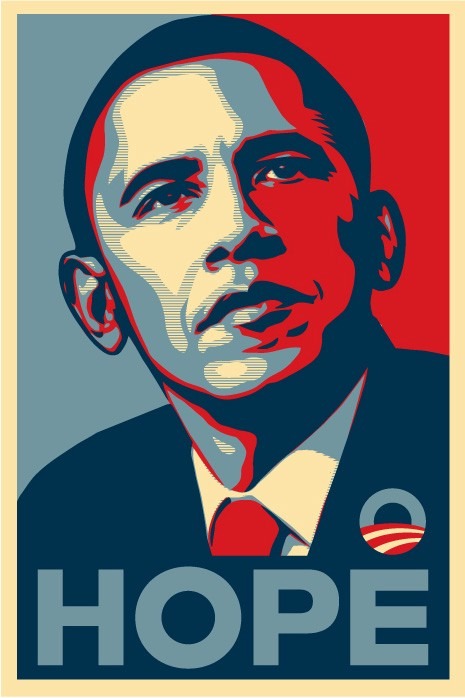

Are such people still heroes, then? At what point does someone go from being a flawed hero to a villain? If courageous acts are what makes a hero, then they’d certainly still qualify (though, it should be noted, so too would someone like Genghis Khan). If we also consider as heroes those who demonstrate a “nobility of character,” then someone like Barack Obama, one-time harbinger of hope (and still idolized by American liberals), would count as a hero too – though some might dispute this, citing his drone strikes, which have killed hundreds of civilians, and his construction of the infamous border cages that Donald Trump was later blamed for, to name just a few of his misdeeds. But then again, whether or not someone is noble — acting from integrity and high moral ideals — is very much a matter of perspective. For some, Obama’s drone strikes might be unforgivable, while for others, they might signify true leadership and the willingness to make hard decisions.

But maybe we shouldn’t be so concerned with who’s a hero and who’s not. After all, branding anyone brave, noble, or a hero is as disingenuous as branding anyone who commits a transgression a villain. Both acts are reductive and fail to encompass that person’s whole character. Viewing famous people as heroes or villains, as white or black, denies both their humanity and our own. As cultural commentator Ayishat Akanbi said, “The inability to accept complexity is the inability to accept it in yourself.” We can learn more from these people by taking a more nuanced view.

Viewing famous people as heroes or villains, as white or black, denies both their humanity and our own.

Lifting anyone up as special, even those who have accomplished great deeds, sends the message they are “more” than us in some way — whether braver, stronger, smarter, or more talented. This creates a separation between them and us that can discourage us from emulating them and achieving our own greatness. And when these people fail, as they sometimes will, many of us become disillusioned entirely, which leads us only into despair or, worse, a nihilism under which we scorn the values we once believed in. Instead, however, we can choose to learn from these failings, studying these mistakes without having to make them ourselves. We can always benefit by looking to others to see what positive traits we can incorporate into ourselves, as well as what negative traits we should guard against.

It’s easy to look at the heroes of the world and feel small, just as it’s easy to look at the villains of the world and feel virtuous. But in doing so, we miss the valuable lessons they can teach us. When we stop being so hung up on heroes and start to recognize them as human, we give ourselves permission to take matters into our own hands and pursue our own heroic quests. The remarkable might then become the mundane, but, in a sense, isn’t that what heroes are for? “Only a hero,” wrote Norman Mailer, “can capture the secret imagination of a people, and so be good for the vitality of his nation; a hero embodies the fantasy and so allows each private mind the liberty to consider its fantasy and find a way to grow. Each mind can become more conscious of its desire and waste less strength in hiding from itself.” A hero leads by example, and that example doesn’t have to be perfect.