The One-Child Policy and the Rewriting of History

By Mahlon Meyer

Contributor

9/6/2019

Sitting in the hushed darkness of a movie theater in Seattle, a woman emits a low moan. The moan is taken up by another woman a few seats away. Another woman begins to cry, softly. Soon snuffles are heard around the theater. One person breathes out an almost inaudible, “Oh my God.” On the screen flash images of pink and orange fetuses discarded among mounds of decaying trash.

Such reactions are common during screenings of this film. The film, One Child Nation, made by Nanfu Wang, a Chinese filmmaker who lives in New York, opened at the premiere Sundance film festival this January. It was then shown in other leading film festivals around the country, including in Utah, Missouri, Florida, Chicago, and in Seattle at the Seattle International Film Festival, where reports attest to similar emotional responses. It will be shown in film festivals over the next few months in the UK, Australia, New York, Aspen, and Israel. It is scheduled for a much anticipated popular release later this year.

Critics, too, have had strong reactions to the film. The New York Times called the film “essential” to understanding China. Variety described the film as a harrowing portrait of a totalitarian state gone out of control with barbaric policies. Likewise, even minor newspapers around the country have weighed in, lambasting China for implementing the one-child policy, which the film explores. The Northwest Asian Weekly in Seattle, for instance, called it “damning,” and added that its only flaw was that it tried to cover too much ground in just 90 minutes.

On the surface, the film is meant to show the cost of the one–child policy, a desperate measure implemented by Deng Xiaoping to restrict women to birthing just a single child. The policy kicked off in the early 1980s soon after a Chinese census showed that the population had exceeded a billion people. It ended in 2015, by the order of Xi Jinping, the current president, who has been made dictator for life.

The one–child policy was the reaction of a government facing a Malthusian nightmare. At the time it was implemented, the cultivated land available to each person in China was 0.25 acres – perhaps not even enough to sustain life (in the US, it was 10 times as much at 2.1 acres per person).

Planners were aware of the massive famines that had hit China in the previous century, for instance at the end of the 19th century, when starvation and overpopulation had sent millions of Chinese fleeing overseas in the first great mass migration that spread Chinese refugees throughout the world, from guano pits in South America to sugar plantations in Hawaii to the West Coast of the United States to work as miners, railroad laborers, and canners.

However, like many other important details of the policy, the filmmakers gloss over this history. It’s mentioned only as propaganda in the mouth of a tired old woman as she explains that she sterilized tens of thousands of women as a government health official. Others, for instance an elderly relative of the filmmaker who gave a daughter away so the family could try to have a son, simply repeats over and over, “We had no other choice.”

For that matter, the film appears to have been made — like most Chinese independent films — with the tastes of US audiences in mind, especially as an abortion debate roils again through American national politics.

One Child Nation commences with a long, lingering shot of an unknown object. The object resolves itself into a blue hand with fully formed fingers. The camera angle rotates around the object so the viewer can see it’s the body of an infant. The infant appears blue on the screen, leading the viewer to imagine the image is computer generated, so unreal and ghostly does it appear. Later in the film, viewers realize that the body is in fact real. An artist has retrieved the corpses of dead fetuses, aborted in the final weeks or months, from trash heaps, and preserved them. They have been preserved in liquid in glass jars kept on the artist’s shelves for years, ever since the one-child policy ended.

An artist has retrieved the corpses of dead fetuses, aborted in the final weeks or months, from trash heaps, and preserved them.

The film also spends a great deal of time following the fate of female infants who were abandoned on the roadside. Some were left to die. Others were taken up by garbage collectors or gangsters and sold to orphanages. These were then adopted, in some cases, by American couples. The film concludes with the story of an American couple — the husband is white and the wife is from China — creating a large computer bank of adopted Chinese children in the United States. Their goal is to help these adopted children find their original birth mothers back in China.

The film, however, fails to put the practice of female infanticide into any historical context. This is not an unimportant mistake. In fact, by linking female infanticide to the one-child policy, the filmmaker is grossly distorting the practice. In doing so, the filmmaker is engaging in the kind of propaganda she allegedly wishes to impugn.

In fact, scholars have shown that female infanticide has existed at least since the Song Dynasty, and probably from even as early as the Han Dynasty. The practice has existed for thousands of years, not as a result of a relatively brief policy that spanned three decades in the twentieth century, but rather as part of the very nature of traditional Chinese civilization itself: a civilization based in rice farming and patrilineal descent, in which a family reckoned its survival on how many hands it could field. Daughters, who were to be married into other families, were simply mouths to feed until they left home and thereafter could not provide agricultural labor.

If the film had grounded its critique of female infanticide in this history, the story might have been more compelling. It might have shown that Chinese women for thousands of years, in fact, have been lamenting the lowly status of daughters in Chinese families. As early as the Han Dynasty, Ban Zhao, the sister of a famous historian, wrote that, “In ancient times, on the third day after a girl was born, people placed her at the base of the bed. She was put below the bed to show that she was lowly and weak and should concentrate on humbling herself before others.”

The film might also have shown that resistance to female infanticide predates the one-child policy. At the beginning of the 20th century, reformers, inspired by Western ideas of rights, called for the end of female infanticide. One of the most famous revolutionaries in the period leading up to the Republican Revolution of 1911, Qiu Jin, a woman who rode on horseback, studied espionage in Japan, and taught her students to make bombs, advocated tirelessly against the practice.

Still, one might argue that the film simply captures the devastating consequences of the one–child policy with no need for historical background, like a photograph captures an instant in time. This might seem to make sense. The film shows photographs of women being transported, bound and struggling, to rudimentary abortion clinics. It shows abortionists, government minions, who talk ruefully about their victims. It details instances of abortions being carried out on 8– and 9–month pregnant women. And then, of course, are all the shots of discarded fetuses.

Clip from One Child Nation

However, here is where the film is perhaps the most unsatisfying and dovetails with American concerns about abortion rights. The film focuses on the fetuses, the dead babies, with no exploration of the complexities of children raised in single-child families. It is essentially a film about dead creatures that may or may not have been human beings, depending on where you stand.

If the filmmaker had been really creative — of the stature of someone like the Chinese writer Lu Xun, who used cannibalism as a metaphor for the fundamental relationship between human beings in Chinese society — she might have suggested that the focus on dead fetuses was more than simply a reminder of excruciating loss and mass murder. She might have gone so far as to suggest that under the current regime in China, all Chinese people are unborn fetuses discarded on a trash heap and preserved in chemicals.

That is, she might have linked the abortion of so many millions of Chinese babies to any one of the liberal Western critiques of China today — an education system that stultifies the development of critical thinking, repression of human rights, systematic erasure of memory by denying people the right to study their country’s true history, an environment marred by pollution that gradually harms people’s health.

Many social scientists studying the effects of the one–child policy are more concerned with the psychological impact of children growing up in families without siblings and catered to by four grandparents. Some worry that “singletons,” as the Chinese of that generation are called, may have grown up self-centered. If true, that would essentially apply to many Chinese people today under forty — the future leaders of the country. As Jing Xu, an anthropologist at the University of Washington, said, “There is a big controversy around what has happened to children in families in which the basic structure has fundamentally changed compared to the traditional model.” (Today, Jing noted, China is embracing “a strong pronatalist culture,” encouraging births).

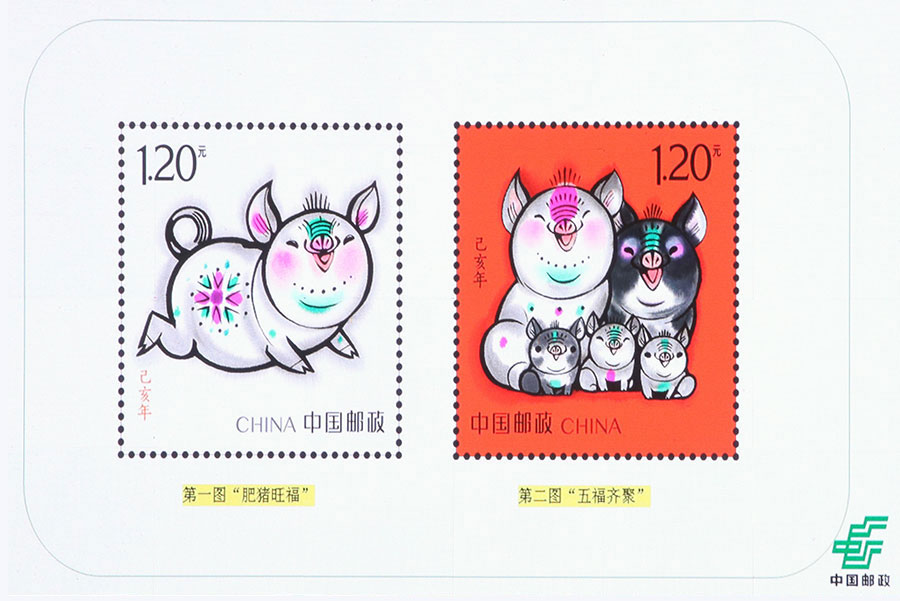

Chinese postage stamps for the Year of the Pig in 2019. The presence of three piglets was viewed by many as signaling easing birth policies.

So is the documentary simply sensationalism — like a beggar sitting in a traditional market showing off an amputated limb to get pity or attention? Clues within the film suggest a different reading. At one point, as the filmmaker is trying to interview a village headman who implemented the one—child policy, his wife screams at her that “just because her uncle is an official” doesn’t give her the right to do whatever she wants.

When I was a Newsweek correspondent in China in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s security was tight. Once, driving into a remote village in Fujian Province in a taxi, a Chinese police car pulled up on the other end of the road just as I began to step out of the car — so fast had the news spread of a foreign reporter arriving. My colleagues and I, even the Chinese Americans, were arrested, harassed, and kicked out.

And yet the filmmaker walks through villages and major cities, and public train stations and squares with her camera held high, filming with impunity. At one point in the film, we can even see her reflection in a mirror, holding a video camera aloft. She films her uncle, family members, and officials in different parts of the country. How did she get such access? Is it possible to shoot a film so freely, especially about such a controversial topic, in China these days? Does her uncle, an “official,” help her get approval?

The answer is unclear. However, an analysis of the arc of the movie itself suggests a different reading of the film. The film deftly shows the barbaric treatment of pregnant mothers and the abandonment of millions of fetuses. It closes, however, with a recapitulation of many of the main characters repeating over and over that it was policy and that they “had no choice.”

The implication is that now that the policy has been banned — by no less than Xi Jinping — people can finally grieve and lament and see it for what it was: the act of a callous totalitarian state. The structure of the plot then creates a counter narrative that implies that Xi has loosened China from the grip of horror, allowed people to vent their complaints about past practices and opened an era of liberal truthspeak.

The structure of the plot creates a counter narrative that implies that Xi has loosened China from the grip of horror.

The opposite could not be truer. Rarely has free speech or mourning for past tragedies been more repressed. However, not only Chinese politicians, but also artists and writers are now engaged in a mass social project to remake history and elevate Xi Jinping and his family at the expense of Deng Xiaoping. Whilst it is impossible to prove that the filmmaker was intentionally part of this effort, her film can certainly be seen to be part of this zeitgeist.

As has been reported in the New York Times and the Financial Times, workers in the southern city of Shenzhen completely revamped a museum dedicated to Deng Xiaoping and his policies of economic invigoration that had traditionally been recognized as elevating 400 million Chinese out of poverty. Before Xi Jinping assumed the presidency, biographies of Deng were routinely published in the US and China, hailing him as “the greatest leader of the 20th century,” as one hagiography put it. However, since Xi tightened his grip on power, even the museum in Shenzhen was given a facelift to show that it was Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, rather than Deng, who was responsible for much of the economic transformation.

None of this is new to Chinese history. In imperial China, founders of new dynasties would force the historians of the outgoing dynasty to write a new history. Of course, the new emperor was painted in the most glowing terms possible, whilst emperors of earlier dynasties were now shown to be scoundrels.

Whether this new filmmaker (historian) of China intends to follow such a tradition is not entirely clear. But her work certainly fits with the prevailing attitude among most establishment artists, cultural workers, and media savants in China — that Xi Jinping has freed China from many of the unjust, decadent, and corrupt practices of his predecessors. What is interesting is that Deng Xiaoping, according to a recent article in the New York Times, used the same tactics.

Whether or not Americans watching One Child Nation will come away with the impression that Xi Jinping has saved millions of unborn Chinese children and done away with the barbarism of Deng Xiaoping is unknown. They will certainly come away with the impression that China was more barbaric in the past. They may even come away with the impression that 2015 was a turning point, when the policy was ended. Who knows? It would be a perfect film to show a Republican pro-life convention in the United States. They might even get the impression that Xi Jinping was one of them.

The truth is that the Chinese government eradicated the policy to pacify the middle class and to provide a young work force as the population ages. But the American viewers crying softly in the audience may not know