The Polling Crisis

By Eve Bigaj

Staff Writer

23/12/2020

“Don’t sweat the polls,” The Atlantic reassured us this October. In 2016, forecaster Sam Wang vowed to eat a bug if Donald Trump won – and ended up having to. The memory was still fresh, but in the intervening years pollsters had worked hard to regain our trust. As The Atlantic (and just about every other respectable publication) explained, the 2016 error was due to late deciders and the failure to weight by education. This year, most voters had made up their mind long before the election and pollsters had corrected the weighting mistake. Everything would be fine.

When the 2020 results came in, the reassurances vanished like a puff of smoke. Not only was this year’s statewide error as large as in 2016, but each major national poll was off by at least 3.5 points, while the Senate polls were even worse than the general election ones.

America is in the middle of a polling crisis – or is it? FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver told us there’s no need to panic. After all, the magnitude of this year’s polling error was about average by historical standards (that is, from 1972 onwards). Indeed, the 2020 error is nowhere near as bad as 1980’s, when state and national polls were off by nearly 9 points, completely missing Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory over Jimmy Carter.

Silver is right that the magnitude of this year’s polling error is historically unremarkable, but history holds other lessons too.

Historically, most polling failures have been due to unique factors, which never recurred in other election cycles. When FiveThirtyEight compared the biases in polls between 2000 and 2012, it found that “the accuracy of a state’s polls one election does not appear to have any bearing on their accuracy the next.” In 2020, that is no longer the case. What is new about the 2020 state-poll error is precisely…that it isn’t new. The general pattern of the 2020 error matches the 2016 pattern: by and large, the polls overestimated Democratic support in the same states and to similar degrees as in 2016. More precisely, there is a small but statistically significant correlation between the 2016 and 2020 state poll errors. (The correlation is larger for the Midwestern states which decided the 2016 election.)[1]

What is new about the 2020 state-poll error is precisely…that it isn’t new. The general pattern of the 2020 error matches the 2016 pattern.

Why would there be such a correlation? The simplest explanation is that, despite their best efforts, pollsters made some of the same mistakes in 2016 as in 2020. If that’s right, those mistakes may be difficult to avoid in the future. And so even if, as Nate Silver claims, we’re not in a polling crisis yet, we may be headed towards one.

Nate Silver (Picture Credit: Treefort Music Fest)

Why did the polls fail this year, and are they likely to fail again? To answer these questions, I talked to data analyst David Shor, who developed the Obama 2012 campaign’s election forecast and until recently operated an internet survey at consultancy company Civis Analytics. But before I walk you through what I found, you’ll need to know a little about how polling works (or fails to work). So please take a moment to imagine you’re an American trying to predict how your neighborhood will vote. Assuming you can’t survey everyone, you’ll need to find a way to contact a random subset of the residents. Following the practices 0f the most highly regarded polling firms, you might accomplish this by randomly dialing cell phone numbers with the appropriate area codes.

Why did the polls fail this year, and are they likely to fail again?

Now imagine that you’re dialing those random numbers and asking people how they’ll vote. What determines how accurately the responses reflect voting patterns in your neighborhood? First, there’s simple luck. If you survey just a few people, by pure misfortune they might all be Biden supporters. As you dial more (random) numbers, the ratio of Trump to Biden supporters will approach the ratio in the neighborhood as a whole – but it’s unlikely to be exactly the same. That’s the first source of error: the margin of error, or the range by which your poll is likely to be off by pure misfortune. Now the margin of error in any individual poll is non-negligible, but since, as far as pure chance is concerned, polls are just as likely to be off in one direction than in the other, this problem disappears in the aggregate; the margin of error of an average of polls will be negligible. So the 2020 polling error as a whole can’t be explained by pure statistical misfortune.

The second source of error is specific to election polling. As you call up your neighbors, the best you can do is find out how they are planning to vote. In the end, they might not turn up to the polling booth. (They might also change their mind, but there isn’t really anything you can do about that – except perhaps poll closer to election day.) To deal with this problem, you might restrict attention to respondents who say they are likely to vote. Or you might create a “turnout model,” predicting which demographics are likely to show up to vote based on past elections and adjust the survey responses accordingly. Many pollsters do either or both of those things.

Let me just get this out of the way: even though the 2020 turnout was the highest in over a century, it’s unlikely to have contributed much to polling error. The 2020 late deciders were by and large split evenly between Democrats and Republicans, so the impact of turnout on polling error would have been at best localized to a few regions. And turnout wouldn’t explain the correlation between the 2016 and 2020 error: why would new 2020 voters turn out for President Trump in just the right numbers to mimic the 2016 pattern? While almost none of the 2016 error was caused by unpredictable turnout, some of it was attributable to late deciders. But since this year the polls saw much fewer undecided voters, that wasn’t the 2020 problem either.

The final source of error, sampling bias, is the crux of the matter. If you only call up the richest (or poorest) residents of your neighborhood, the answers probably won’t reflect the place as a whole. Your sample is unrepresentative. Dialing random phone numbers used to solve this problem, but these days it’s not so easy. In the era of landlines, each household would have precisely one phone number, naturally corresponding to their address and easily accessible in the phonebook. Today, more than 60% of Americans lack a landline. And cell phones don’t neatly correspond to addresses the way landlines do; for example, a transplant from one state to another will often keep her old phone. Such a person can vote in her new place of residence, but because of her phone’s misleading area code, she isn’t part of the pollsters’ sample. (This is part of the reason some pollsters elect to choose numbers from the voter registry instead – but this introduces other problems, like missing voters who register at the last minute.)

Sampling bias is the crux of the matter.

Pollsters have ways around the cellphone problem, but it gets worse. If you try out our little experiment and dial the numbers of strangers, you’ll hear the hang-up tone more often than their voices. With the rise of caller ID, ever growing number of spam calls, and a general fall in trust, Americans are less and less likely to respond to phone calls. In 1997, 36% of Americans responded to polls. Today, response rates are as low as 1%. This means that pollsters’ samples are no longer representative; the 1% of Americans quirky enough to answer polls differs from the population at large in many respects.

To make up for low response rates, pollsters apply demographic “weights” to survey responses. In other words, if the sample contains fewer members of a given demographic (e.g. Black men with a college degree) than the population at large, the responses of this demographic will count for more than the responses of overrepresented demographics. Essentially, pollsters are extrapolating from the survey responses they do get to the ones they think they would have gotten if the demographic ratios in their sample matched reality.

Weighting played an important role in 2016, when voters without a degree were disproportionately likely to vote for Trump. Since many pollsters failed to weight by education, the fact that such voters are also less likely to respond to polls contributed to the polling error. That was the mistake pollsters promised to fix in 2020…and now you know everything you need to know to understand David Shor’s explanation of why the polls were off anyway.

Trump rally in The Villages, Florida, October 2020 (Picture Credit: Whoisjohngalt)

Shor told me that the 2020 error exhibited the same patterns as the 2016 error, plus an additional bias in favor of Democrats, which explained the national polling error. Let’s consider this additional bias – a bias that was not present in 2016 – first.

In March 2020, Democrats started responding to surveys in unusually high numbers. It’s not hard to come up with explanations why. Democrats are likelier to self-quarantine and to hold the types of white-collar jobs that can be done from home – so they were simply likelier to be home to answer the phone. They also generally became more politically engaged during this time – perhaps because they were concerned with how Trump was handling the pandemic – which further manifested as a heightened likelihood of answering surveys. Finally, if you’re sitting home all day, you’re likelier to answer a survey out of pure boredom.

Shor also put forward some data that's at least plausibly consistent with it. The increase in Dem response clearly happens before the pandemic, in the primary. But maybe it held because of the primary pic.twitter.com/aH9Q3rMqpp

— Nate Cohn (@Nate_Cohn) November 10, 2020

This all sounds obvious in retrospect. Couldn’t the pollsters have noticed this possible source of error before the election? “Something like COVID-19 was a big enough event that it might make sense to stop and think how that could affect the accuracy of the polls. As far as you know, is that something people did?” I asked.

“People actually thought about it a different way: more people are responding, so that means that there’s less response bias,” Shor confessed. We both laughed at the irony, then Shor continued: “It all sounds obvious in retrospect, but I remember people were really excited. Their costs went down, it was easier for them to recruit.”

As Shor explained, polls’ abysmal response rates cause not only sampling error, but also skyrocketing costs. Every time the response rate is halved, the time it takes for the polling firm to get a survey response doubles. And with every increase in time per response comes an increase in the cost of employing the poor souls who are hung up on 99 times for every interview they manage to conduct. (Federal law prohibits automated cell phone polls.) In 2012, a single survey response cost $3 or $4; by 2016, that number was up to $20. Is it any wonder that pollsters met March’s rising response rates with relief instead of skepticism?

Still, there are many pollsters in competition with each other – shouldn’t that pressure them to be more accurate? Shor explained that there’s pressure to be more accurate than other pollsters, but not to be actually accurate. “If you’re getting numbers that are roughly in line with what everyone else is getting, I think it’s very easy to be complacent. And I’m guilty of this too, you know, as a practitioner. It’s a very rational thing to do. Most of the time when your numbers are totally different it’s because something went wrong.”

“If you’re getting numbers that are roughly in line with what everyone else is getting, I think it’s very easy to be complacent.”

The flipside of being complacent if your results match everyone else’s is “herding:” tweaking your methodology when they don’t. “As a practitioner, I herd all the time,” Shor admitted. “I’ll consider a change, and if it makes things really weird and really different than what other people are doing, then I’ll be like ‘Oh, this is probably wrong,’ and I’ll dig into it and I’ll usually find something.”

Polling organizations are small, Shor said, so there’s no one with whom to, for instance, compare turnout models, and little time to solve problems from scratch. (He recalled being forbidden to discuss methodology with competitors.) So pollsters “herd” without being able to tell whether they are simply following other herders.

As a practitioner, Shor is right to herd. He is likelier to have made a mistake – or just to have gotten unusual responses due to pure misfortune – than to be right while everyone else is wrong. Despite this, herding decreases the accuracy of the average of all polls taken together. What is rational for the practitioner also hurts the consumer of polls.

The more I talk to Shor, the more I realize just how difficult the pollster’s job is, and how little reward there is for doing the right thing. While response rates plummet and costs skyrocket, the public is more and more invested in polls’ accuracy, and judges pollsters harshly even before the results are in. Ann Selzer, who oversees The Des Moines Register’s uncannily accurate Iowa Poll, explained why releasing atypical poll results is so uncomfortable: “From the time the poll comes out, my Twitter feed, my Facebook feed, my inbox is full of people going ‘You’re wrong! You’re crazy!’” Selzer has the consolation of being (and having been) right; most who stray from the herd don’t.

This brings me, finally, to the surprising correlation between the 2016 and 2020 polling errors. Turns out it’s actually a three-way correlation; while the 2018 midterm polls were unusually accurate, the error they did exhibit was also correlated with the 2016 error. For three election cycles in a row, pollsters’ errors have exhibited the same state-by-state pattern. The simplest and likeliest explanation for such a repeated pattern is an underlying cause common to all three elections.

Shor thinks that common cause lies in those plummeting response rates. “If 50% of people aren’t answering your calls, that’s one thing. If 1% of people are answering your calls, that 1% is super weird,” he said. That 1% is, on the whole, much more highly educated, more trusting (of people and institutions), more agreeable, and more interested in politics than the average American. These differences didn’t use to matter, because the ways in which survey-takers were weird were unrelated to how they voted. In 2016, that changed.

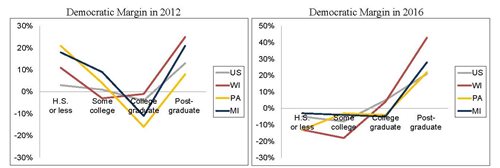

Take education. Over many decades, and across multiple countries, higher education has been becoming increasingly correlated with voting for the left-leaning party. But before 2016, in the US this correlation was dampened by a subtler “u-shaped” pattern within education groups: the least educated voters (those with at most a high school degree) voted similarly to the highest educated (those with post-graduate degrees). Therefore, respondents with post-graduate degrees, who are especially overrepresented in polls, could more or less stand in for the least educated respondents, who are underrepresented. In a way, then, it wasn’t so much that pollsters were unlucky in 2016 as that they were lucky before 2016, when the overrepresentation of the overeducated and the underrepresentation of the undereducated in their samples cancelled each other out.

Democratic Presidential Vote Margin in 2012 and 2016 by Voter Education Level and Geography (Source: NEP national Exit Poll 2012, 2016, reproduced from the 2016 AAPOR report)

In 2016, pollsters’ luck ran out, and now they have to weight by education. That’s harder than you might think, since there is no good source of data on education levels; the American Community Survey and the Current Population Survey, two different government surveys, give conflicting numbers of educated citizens. Things get even trickier when pollsters try to combine education with other weights. For instance, if educated Americans in rural areas vote differently from their educated peers in cities, accurate weighting will require county-by-county education data, which is even less accurate than state-level data.

Still, weighting by education is a solvable problem. (Shor explained that he gets around the inconsistencies between government surveys by choosing the one that would have made past polls more accurate.) Unfortunately, the other unusual features of survey takers affect voting behavior even after you control for education. Take social trust. “High social trust” people are those who agree with the statement “Generally speaking, most people can be trusted;” those with low social trust instead agree that “Generally speaking, you can’t be too careful in dealing with people.” According to the General Social Survey, only 30% of Americans have high social trust. (“Oh, but can that survey be trusted?” you ask. I think so; it has a 70% response rate.) By contrast, if you ask a participant in a typical phone survey whether people can be trusted, you’ll find that 50% of respondents will agree. This makes a lot of sense; if you think that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people, you might prefer not to talk to strangers on the phone at all.

Starting in 2016, social trust became correlated with vote. The correlation holds across demographics; for instance, high-trust whites without college degrees are likelier to vote for a Democrat than low-trust whites without degrees. This means that even weighting by education wouldn’t have removed the full polling error in either of the past two presidential elections.

If weighting by education is hard, then weighting by traits like social trust is practically impossible. There is no data on how these traits are distributed across geographic area, or how they interact with, say, race or gender. And given that the subject of study is precisely those unwilling to answer surveys, gathering such data would require a Herculean effort backed by vast monetary resources.

Given the falling response rates to phone polls, it was only a matter of time before one of the quirks of survey respondents became correlated with vote. “I was always in a state of existential terror over the idea that our polling could be wrong in some way,” Shor confided. “The problem is that there are just so many different ways that things could go wrong. People who answer surveys are just so weird! There can be 30 different things that you have to try to fix and you fix 16 of them but not the rest.”

Given the falling response rates to phone polls, it was only a matter of time before one of the quirks of survey respondents became correlated with vote.

Something shifted in my mind. “Why were the polls off after 2016?” no longer feels like the right question to ask. In the 1980s, 50% of people responded to polls. By 2012, that number had fallen to 9%, and yet poll accuracy remained roughly constant.

So the real question is “Why were the polls so accurate before 2016?”

Shor is as puzzled as me. “It’s incredible to me that polling has worked as well as it has.”

Perhaps there’s a more satisfying answer: in 2000-2012, Americans may have been unusually predictable. Landslides like Reagan’s don’t happen anymore; in the 21st century, 80% of the electorate has voted according to party affiliation. Demographics further predict vote: given somebody’s county of residence, race, sex, and education, in 2000-2012 it was possible to predict that person’s vote with a high degree of accuracy, without conducting any surveys. Perhaps this is why polls in the 2000s maintained the same level of accuracy as previous decades: demographic predictability helped offset lower response rates. As Nate Silver pointed out, this hypothesis is supported by the relatively poor accuracy of primary polls in this era, since voting in primary elections is affected by demographics to a far lesser degree than in general elections.

This suggests one more source of the 2020 error: traditional demographic coalitions are falling apart. Though Black and Hispanic voters still lean heavily Democratic, an increasing proportion has been swinging towards the Republicans. Black and Latino respondents have always been underrepresented in surveys. Given that they are increasingly inhomogeneous in their voting habits, weighting such a small sample is likely to misrepresent them. This is the final piece in the polling error puzzle: some of the error in Florida is probably explained by the shift in support among Hispanic voters.

Trump at the Latino Coalition Legislative Summit, March 2020 (Picture Credit: The White House)

There’s something else, though, something I’d rather not tell you about, a recalcitrant fact I haven’t been able to fit neatly into my narrative. The bravest pollsters publish “outliers:” surveys whose results don’t line up with any of the other polls. I want to be brave too, so here goes: the outlier in my story.

After talking to Shor, I think I understand it all. Social trust (along with the other traits which make people likelier to answer phone calls) is so low and so correlated with political views that traditional phone polling is basically dead. And as the costs of phone polls rise, internet polls are becoming a viable alternative. They face their own problems, but they are no longer less accurate than phone polls. That’s despite the fact that the participants of a given online survey – say, people who click on a Facebook ad for that survey – are far from a representative sample of the electorate: online survey respondents are likelier to be self-employed or on disability, for instance. Online pollsters try to make up what they lack in sample representativeness with a combination of survey size, weighting, and mathematical modeling. That’s where the future lies, Shor told me. “There are no more A+ [phone] pollsters.”

Except…there are. More precisely, there is one A+ pollster: Ann Selzer. Since the nineties, Selzer’s Iowa Poll has been consistently getting things right when no one else did. She was the only pollster to predict Barack Obama’s victory in Iowa’s 2008 Democratic caucus. And yet, judging by what Shor told me, she does everything wrong. She weights less than other pollsters, not more. (She rarely weights by education, for instance.) She only includes responses among those who say they are “very likely” to vote, even though 95% of survey respondents actually vote. She doesn’t use a turnout model at all. While every other pollster complains about falling social trust, somehow the people who answer her surveys are representative of the population at large.

There are so many pollsters that someone is bound to be right multiple elections in a row. Is Selzer just that person? I don’t think so. FiveThirtyEight dubbed her “the best pollster in politics” before the 2016 election, and her polls have continued to be accurate since then. That’s not what you’d expect from pure luck.

So what is Selzer’s secret? I have some hypotheses, but remember: what you’re about to hear is motivated reasoning. I’m just a journalist trying to fit things into a coherent narrative on a deadline.

There are two ways I think Selzer might be getting her uncannily accurate results without disproving the existence of a polling crisis. First, she hasn’t released her response rates, and they may be higher than other pollsters’. She mentioned in an interview that she trains her callers in politeness, or what she calls “Iowa niceness.” Perhaps this makes her respondents less likely to hang up. Second, Selzer’s extremely simple method probably wouldn’t work in states other than Iowa. When Patrick Murray, the founding director of Monmouth University’s Polling Institute, tried following Selzer and eliminating turnout models from his polls, he saw no change in accuracy in any state except…Iowa.

Convinced? Good. Now let’s proceed as if I never mentioned Ann Selzer.

Inaccurate polling has real-world consequences: it can depress turnout by giving the false impression of a blowout or cause candidates to campaign in the wrong places. But the implications are more serious than this.

Inaccurate polling has real-world consequences.

Take, for instance, the poll which found that 80% of Americans support strict quarantine measures. What can we conclude from that? Nothing more than that 80% of those Americans who are answering the phone during the pandemic – and hence who are likelier to be respecting quarantine guidelines – support these guidelines. That’s barely more meaningful than a survey about…how likely you are to answer surveys.

COVID-19 will pass. Trump will fade to a hazy memory. But many of the issues facing phone surveys will remain. Social trust has fallen from 45% in 1980 to 30% in 2018; phone response rates have dropped even more sharply. These trends are unlikely to reverse anytime soon, and so the difficulties that have plagued the past election cycles are here to stay – and will likely worsen.

Pioneer pollster George Gallup once compared polling to soup-sampling: “As long as it was a well-stirred pot, you only need a single sip to determine the taste.” Unlike vegetables, people have to consent to be part of the mix. These days, most cower at the bottom of the pot, far from the reach of pollsters’ ladles. It’s less like a soup and more like a deep, impenetrable sea.

Politicians rely on polls to gauge the popularity of policies. The less polls reflect reality, the less those in power know about those they govern, and the worse they represent them. In a vicious cycle, the less Americans are represented by their institutions, the less they trust them, and the less likely they are to answer the surveys that would help those institutions become trustworthy.

The polls are broken; democracy is next in line.