The Second Life of Vintage Japanese Singers

By Julien Oeuillet

Staff Writer

31/5/2021

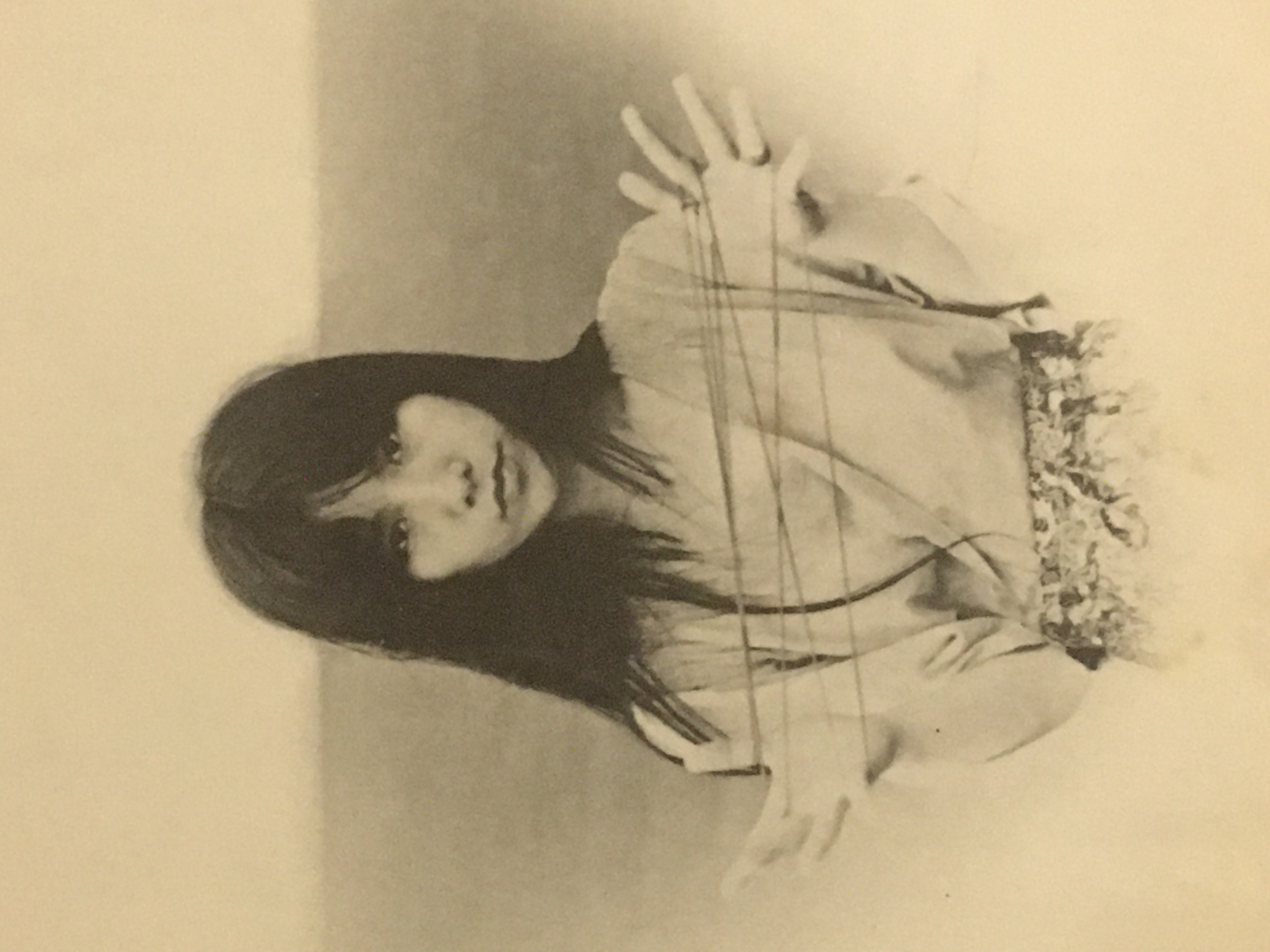

Yoshiko Sai (Picture Credit: H. Kawabata)

I first stumbled upon the music of Yoshiko Sai on YouTube on a cold, dark evening. Melancholy, I decided to embrace the gloom and listen to sad songs rather than trying to force a smile with upbeat music. She turned out to be exactly what I needed. Her music was somber, yet poetic, the kind that transcends language, which is just as well, since I don’t understand Japanese and had no idea what she was singing about.

Sai’s voice is haunting and ghostly, and the melodies of her songs display her full range, leaping from soulful crooning to otherworldly wailing. The instruments form a backdrop of discordant harmony: strings that stay hanging high in the air, piano used almost like a percussion instrument, layers from a Hammond organ that sound like they’re somewhere in between church music and jazz. Her songs invoke feelings of nostalgia and loss, grief and disorientation. And, after creating four albums in the 1970s, this ghostly singer vanished from the public eye.

Perhaps all this is unsurprising, since Sai began writing poems and songs after an early brush with death. As a student, she spent a year hospitalized with a potentially lethal kidney disease. “Before my illness, I was a young girl with no concept of death,” she told me when I tracked her down, “I was very shocked to be faced with the potentiality of my own demise. Suddenly it was in my mind all the time. This probably reflects a lot in my songs.” Indeed, it does.

Sai began writing poems and songs after an early brush with death.

“Before I write a song, I let images come to me first,” she said, “then I put them into words. I am not sure if they have a concrete meaning or not. This is true for ‘Yukionna,’ for example.” This song is an evocation of the Yuki-onna, the snow maiden, a revenant from Japanese legend. Depending on the different tales about her (and the different interpretations of them), the Yuki-onna is either a dangerous winter ghost or a benevolent spirit. Sai’s song uses the tragic timbre of her voice, heartbreaking orchestration, and wintry sound effects to convey a feel of the character. “The same applies to ‘Fuyu No Chikadou,’” Sai added, “where I just wanted to write the atmosphere of walking through an underpass in winter, where I walked every day [to and from] the train station nearby. I felt so cold and alienated there.” The song features electric guitar and Hammond organ, while she sings the verses she wrote as a bedridden, maybe-dying young woman.

Sai has a deep fascination with the writer Kyusaku Yumeno, an author of gothic, sepulcral fantasy novels. In 1977, one of his novels was adapted into a movie, suffused with eroticism and lesbian themes. Naturally, Sai did the soundtrack. Everything about Yoshiko Sai seems poised to create an aura of mystery: her taste for horror writers, her thanatic debut as a songwriter, her savage independence, her ambiguous songs, her retreat from the public eye, and her now rather reclusive life.

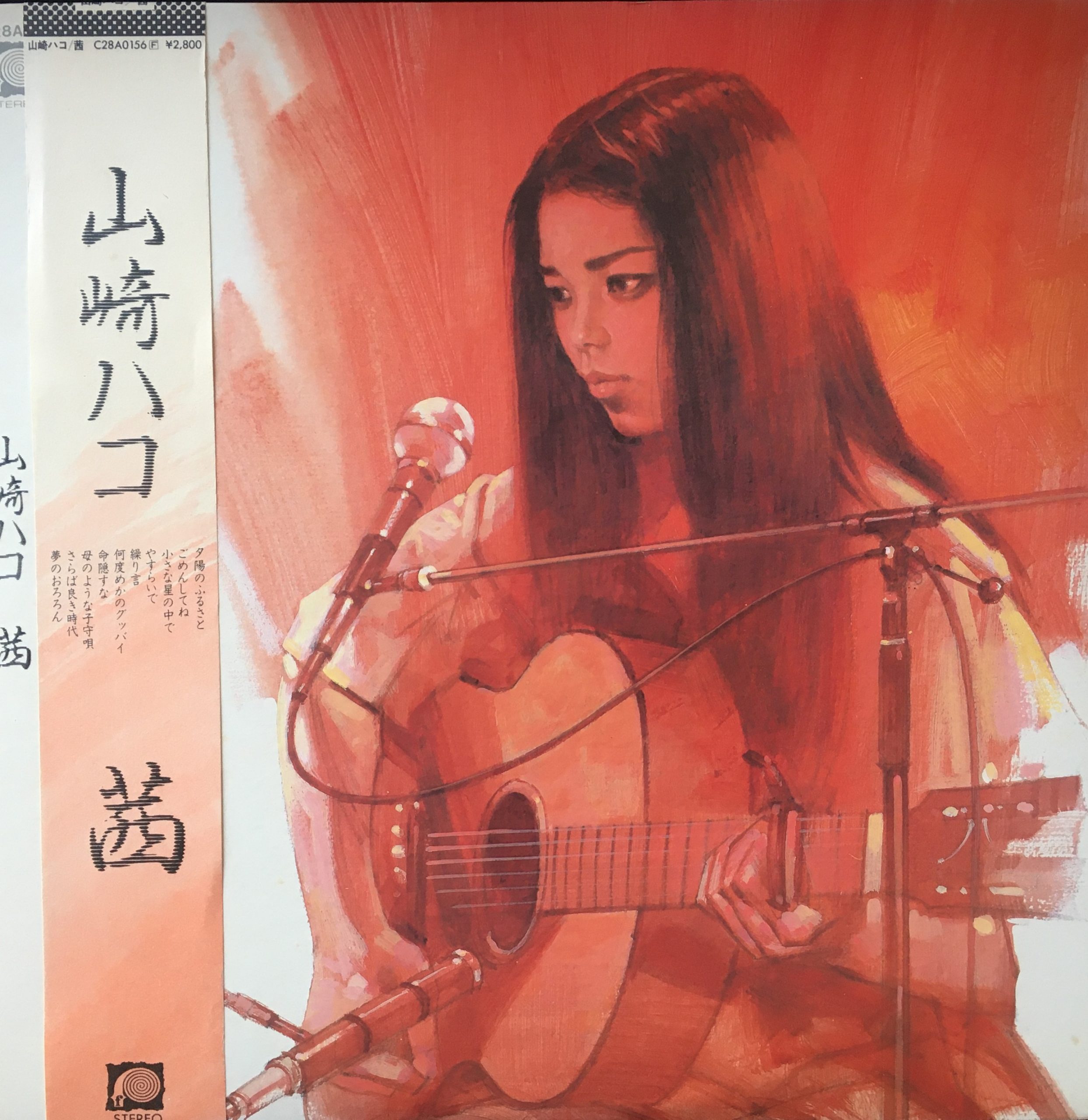

Another melancholy Japanese singer from the 70s is Hako Yamasaki, whose (then) childlike appearance belied the darkness and emotional depth of her music, qualities that come through in the raw intensity of her singing, a rawness that producers, cleverly, seem to have refrained from polishing away. Her instrument of choice is an acoustic guitar, which she plays herself, though the use of a Hammond organ lends an extra solemnity. In one song, “Yoake Mae,” she sings like the world is ending. In another, “Tanjo Iwai,” she sings like the world has already ended and she contemplates its remnants.

Cover for Hako Yamasaki’s album, Akane (1979)

Yamasaki won musical competitions as a teenager and was thrown into the world of professional music at a young age. “I was only 18 when I debuted as a singer-songwriter,” she told me. “My life changed drastically after this; I could no longer live the life of a highschool girl. This is what the song “Aruite” is about: becoming an extremely busy professional singer, so young, and thinking I do not sing because I am happy, I am happy because I sing. I thought, let’s keep singing, let’s pave the way of life.” Unlike Yoshiko Sai, Yamasaki did not opt for a life of relative obscurity after peaking in the 70s, but continued, and continues, to give small performances in Japan, alone with her acoustic guitar.

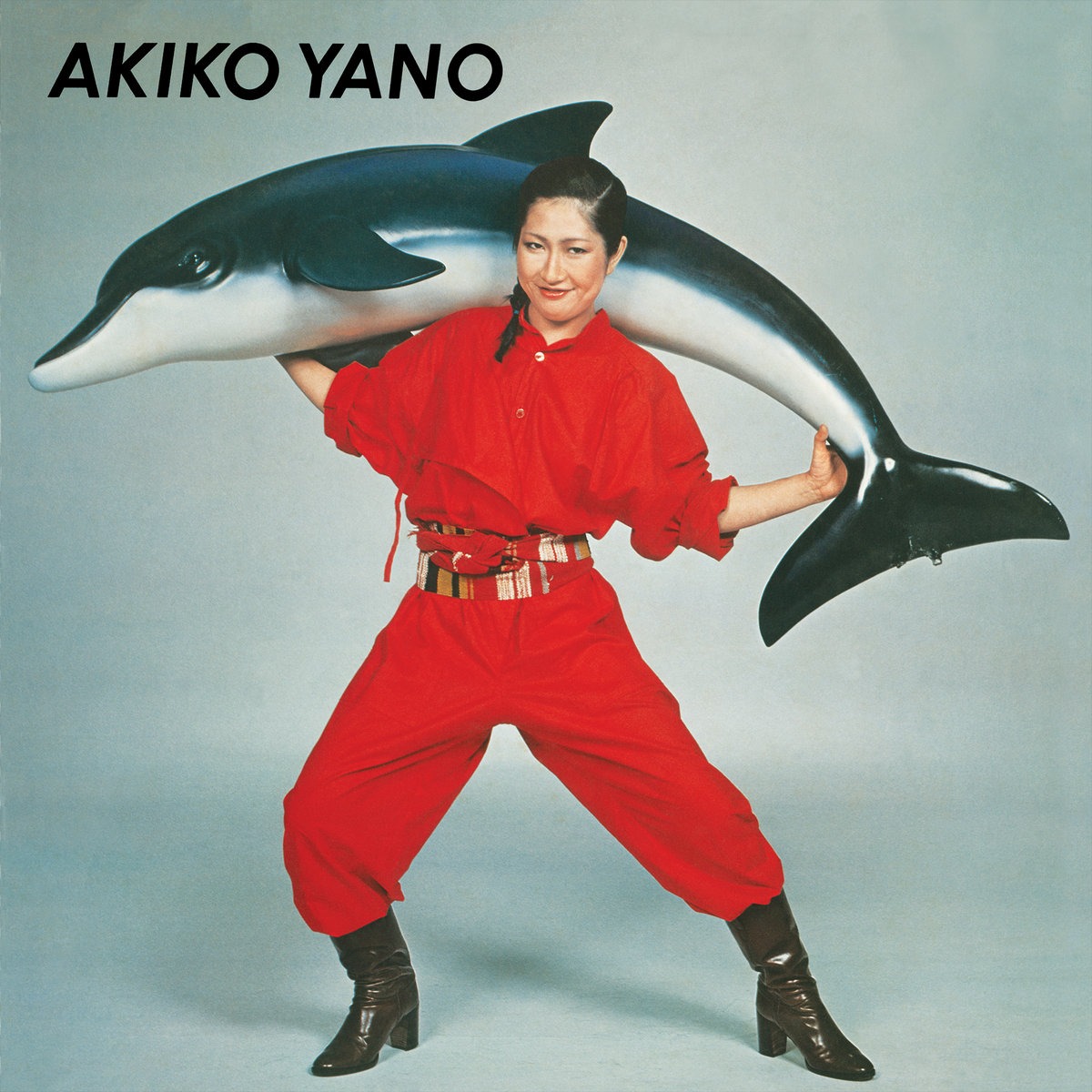

Then there’s Akiko Yano. Much lighter and more cheerful than the other two, Yano’s debut album, Japanese Girl, was released in 1976, and demonstrated her skills as a jazz pianist and a singer. It included strange piano chords, art-pop vibes, and ended with an unexpected, rousing military march that makes it sound like she’s about to storm the Bastille. Throughout Yano’s long career, which has continued to this day, she’s never stopped oscillating between pop, free jazz, and electronic experimentations. As Yamasaki told me, Akiko Yano “has a unique world of her own.”

Yano would later play with Yellow Magic Orchestra, or YMO, Japan’s biggest band in the late 70s-early 80s. One of the pioneers of electronic music, they achieved international success, in part because their upbeat, joyful melodies contrasted with the dark, gloomy tunes of other synthesizer-minded musicians of the era. Yano ended up marrying (and divorcing) one of YMO’s members, Ryuichi Sakamoto, a classically-trained pianist and ethnomusicologist, who composed the soundtrack for The Last Emperor, for which he won an Oscar.

Although ghostly Yoshiko, tortured Hako, and quirky Akiko are very different, the commonalities between them are obvious. All three pioneered female songwriting in Japan, bringing highly personal experiences, sometimes intimate and sad, so different from the innocent songs expected from Japanese women before then. “In the 1970s a lot of women graduated and then focused on marriage,” Yoshiko Sai said, “I wanted to protest against this and prove I could be an independent woman.” Likewise, Akiko Yano commented on how rare it was for a young mother like her to start a career as a singer, in a country where many believed a performer had to be single and childless.

And, today, thanks to YouTube, their old songs are enjoying an uncanny second life. When I first stumbled upon these songs on YouTube, I thought I was special. Part of the magic of its AI is that it gives you the illusion that you discovered videos by yourself, the illusion of agency. Little did I know that I was not alone: vintage Japanese singers have been trending on YouTube, spawning communities of new fans looking for more of their music, and endlessly debating about them in the comments section.

Vintage Japanese singers have been trending on YouTube, spawning communities of new fans.

“The YouTube algorithm is responsible for these successes, and it is kept secret,” said Fabian Pelsch, an German journalist based in Asia who specializes in pop culture. “I contacted them but they refuse to reveal how it works. But whatever the way, an AI created a trend, and this is a new phenomenon. And at the end of the day we never really understand an AI, right? But if you think about it, the reason why one song on the radio would become a hit and another would be instantly forgotten has always been mysterious.”

Although YouTube declined to respond to my requests too, there is no shortage of speculation on how the website decides which videos get put in front of people and which don’t. Marketers have been seeking to exploit YouTube’s algorithm for as long as the site has existed. YouTube itself actively discourages clickbait and aims to find “videos for viewers, rather than viewers for videos.” Ironically, old Japanese singers who did not look for Internet fame found it anyway just by having made good music, and YouTube introduced these vintage artists to an audience who did not know they were waiting for them.

Another reason why some vintage Japanese singers found YouTube fame without even trying, is because the website favors good thumbnails. The sleeve art of old vinyl records is especially appropriate for that. In an era when records came in large dimensions, their packaging was richly decorated with great artwork, something that later disappeared in the era of small CD cases. The cover of Yoshiko Sai’s first album, for example, shows her standing in a dark, windy moor, her fingers tangled in a red thread, the wind sweeping her hair and the long grass behind her.

Cover of Yoshiko Sai’s first album, Mangekyu (1975). Design by H. Kawabata.

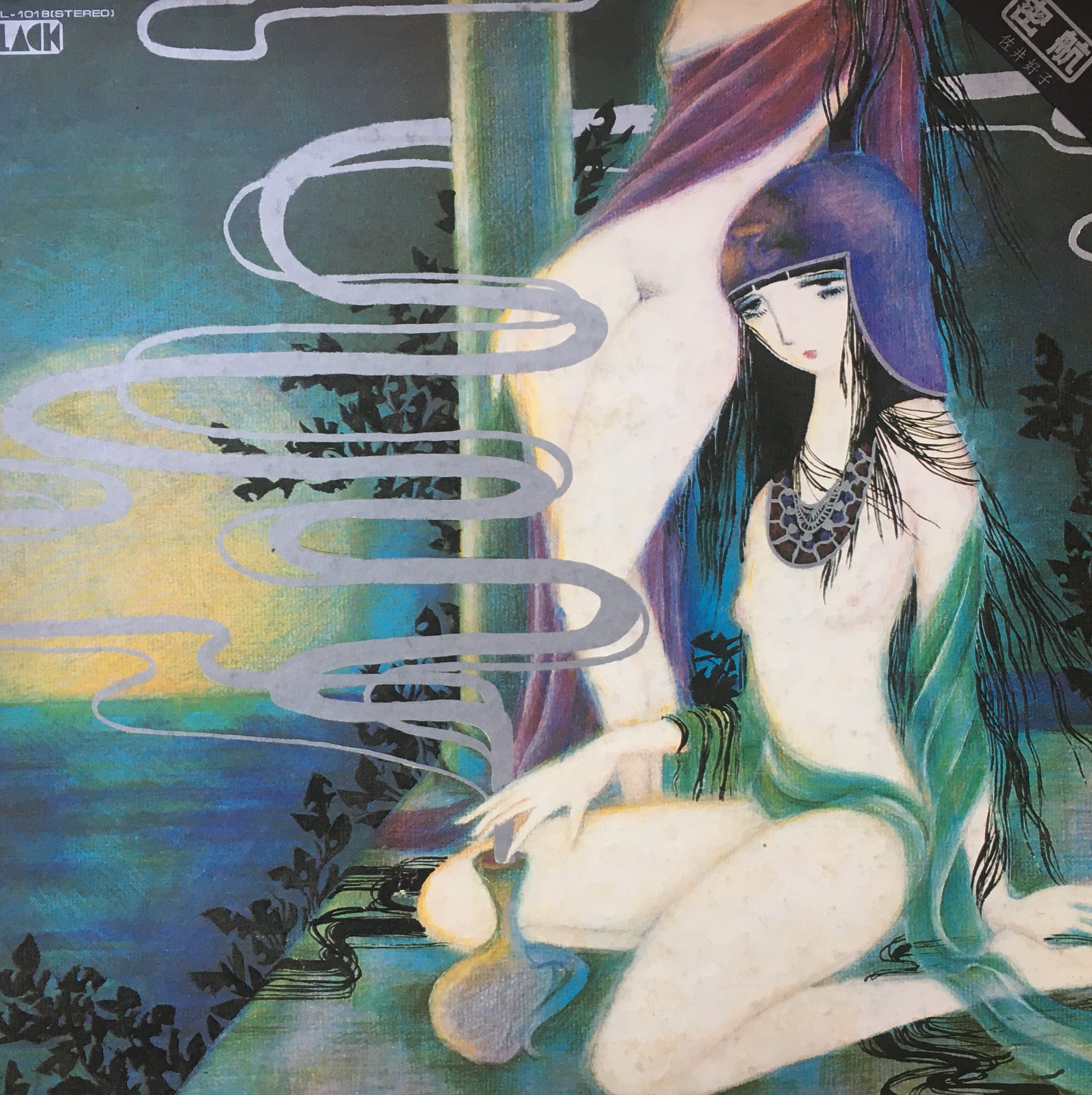

“It was taken in Nara Park,” Sai told me. “We wandered around with the photographer to find the best place in this huge park and ended up in a very remote area with no one around.” This iconic record cover has been reimagined online in countless parodies and homages. “I have seen some of these artworks,” she said, “it was very enjoyable.” Sai, who is also a painter, created the covers of two of her albums herself, which feature eerie paintings of naked girls.

Cover of Yoshiko Sai’s second album, Mikku (1976) featuring her own painting

Similarly, Akiko Yano frequently used pop-art imagery to reflect her unique personality. The cover of her second album shows her clad in red lifting an inflatable dolphin, an image that became very famous in Japan.

Whatever the case, these artists are happy to know their old songs are reaching new listeners.

“I do not receive many letters from fans or anything like that,” Hako Yamasaki told me, “but as I keep my eyes open for music around the world I notice Japanese music resurfacing and it is a wonderful feeling.”

Hako Yamasaki, still playing (Picture Credit: Keiren Kanai)

“I have noticed more and more comments coming from Western people and I enjoy reading them,” said Yoshiko Sai. “I am very happy to know my music reached people through time and space thanks to the internet.”

This second life is a testament to the quality of these songs and the remarkable women who made them, who bucked tradition to express their weird little messages. And now, almost half a century later, my own daughter ranks Yoshiko Sai with her enigmatic pose amongst her fashion icons alongside the latest Korean idols.