The Solomon Islands Torn Between China and Taiwan

By Julien Oeuillet

Staff Writer

30/11/2021

Solomon Islanders during Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen’s visit in 2017 (Picture Credit: Presidential Palace of the Republic of China)

In August 1942, the US Navy and its allies engaged Japanese forces on a small island of the Solomon archipelago in the Western Pacific Ocean: this was the beginning of the Battle of Guadalcanal. For the next six months, the two powers fought ferociously over the tiny piece of land – just like they did for other confetti scattered in the Pacific Ocean.

And once the war was over, everyone forgot about these islands.

Then suddenly, last week, the Solomon Islands, now an independent parliamentary democracy, made the news again. Large-scale riots erupted in its capital, Honiara, which is located on the island of Guadalcanal. A police station and a hut next to Parliament House were set ablaze, and many Chinese businesses have been looted and torched.

Astonishingly, the main trigger for this revolt is foreign policy: more specifically, the government’s decision to turn its back on Taiwan.

Most Pacific islands have very small populations, ranging from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands, surrounded by vast expands of empty ocean. Even as tourist destinations, the enormous distances that separate them from the rest of the world, and the scarcity of transport and facilities make them less desirable destinations than closer places with tropical beaches. As a result, they seldom get much attention, and few countries really care about them.

Amongst the few countries who do care, though, are China and Taiwan, who have both long courted the island nations in the Pacific for diplomatic recognition. Much of this courtship is through “checkbook diplomacy”: offering large sums of money to these small and isolated communities in exchange for recognition as the one true government of China. Pacific Island nations have been known to switch recognition on a dime, or, rather, a lot of dimes, playing China and Taiwan off against each other and recognizing whoever offers them more money. The Solomon Islands recognized Taiwan for 36 years, starting from 1983. This changed in 2019, when it switched recognition to China, reportedly at a price of $500 million in aid from Beijing.

Pacific Island nations have been known to switch recognition on a dime, or, rather, a lot of dimes, playing China and Taiwan off against each other.

But many Solomon Islanders were unhappy with this change.

The Solomon Islands is home to only 650,000 people. But they are very diverse, ethnically and culturally, and live on several islands on the archipelago, sometimes very distant from each other. And although the capital Honiara is located on Guadalcanal island, the most populated province is Malaita island, with each province having its own assembly and premier.

The Solomon Islands (Picture Credit: TUBS)

When in 2019, the prime minister of the Solomon Islands, Manasseh Sogavare, announced his government was abandoning Taiwan for China, a large portion of the population of the country and its politicians opposed what became known in common parlance as “the switch.” Yes, this mattered to Solomon Islanders enough that they have a term for it.

Daniel Suidani, Malaita’s premier, spoke out against “the switch,” and this reflected public sentiment in Malaita so well that his popularity rose – and so did the population’s anger. Generally, Malaita and Guadalcanal often don’t see eye-to-eye. Between 1998 and 2003, ethnic violence between the two islands became a serious concern: Malaitans moving to Guadalcanal in search of jobs were harassed by local militias, and formed their own militia for protection. In the end, a joint contingent of 2,200 policemen from Australia and New Zealand had to intervene.

Malaita is home to 137,000 inhabitants, more than a quarter of the entire population of the Solomon Islands. The province of Guadalcanal and the district of Honiara (officially distinct despite being located on the same island) are home to 158,000 inhabitants. The rest of the population – less than half the total – is scattered in the eight remaining provinces. Profiles of the other provinces describe more traditional communities living in smaller and more isolated settlements with a large variety of ethnicities and local languages (there may be as much as 70 different languages in the Solomon Islands).

But why do Malaitans care so much one way or another whether their country recognizes Taiwan or China?

One theory is that Malaita opposes “the switch” just because Honiara, which many Malaitans resent, favors it. A year ago, Anna Powles, Senior Lecturer in Security Studies at Massey University in New Zealand, said of “the switch” that “Beijing and Taipei are pawns in the long-standing dispute between Malaita and the state.”

Another significant factor is that, whilst both China and Taiwan give aid to the Solomon Islands, Taiwan gives aid more effectively and gets more bang for its buck. Denghua Zhang, research fellow at the Department of Pacific Affairs at Australian National University (ANU), comparing the aid China and Taiwan give to the Pacific region, observed that “The majority of Chinese aid goes into large-scale infrastructure projects in the form of concessional loans […] In comparison, Taiwan’s aid has focused on technical assistance in agriculture and health, government scholarships and small- to medium-sized infrastructure.” Taiwanese aid is more in line with what Solomon Islanders really want. The Economist noted that, for voters, “more important are promises of corrugated iron for roofs,” and that MPs in the Solomon Islands are elected less because of their party affiliation and national politics, and more on whether they can swiftly deliver practical benefits to their constituencies.

Whilst both China and Taiwan give aid to the Solomon Islands, Taiwan gives aid more effectively and gets more bang for its buck.

Zhang and Derek Gwali Futaiasi, another scholar at ANU, noted that “Beijing’s over-emphasis on contacts with the Solomon Islands national government […] places China in a disadvantage when compared with traditional partners that devote substantial attention to grassroots and civil society organizations in Pacific island countries.” A prime example of this is with Constituency Development Funds (CDFs) in the Solomon Islands.

CDFs are basically funds given to MPs to spend on their constituencies. The money for CDFs come through allocations from the state, or from third parties. Taiwan contributed to these CDFs, giving $9 million out of a total of $47.6 million in 2015. However, China has been reluctant to go down this route. John Moffat Fugui, a Solomon Islander MP who now serves as the country’s first ambassador to China, explained that “Beijing told us that for us here in the Solomon Islands, they would provide the rural constituency development funds, RCDF — but just for a transition period […] China doesn’t give such funds […] they told us, we will give you this RCDF for a certain period and then when that’s up, we’d go back to loans for major projects.” In the end, China gave $960,000 to a National Development Fund accessible by 39 of the 50 members of Parliament, all of whom are government MPs. The local chapter of the NGO Transparency International pointed out that the fund was put on an account “jointly operated by Solomon Islands Government and the Embassy of the Republic of China” and lamented that “the beneficiaries of the so-called National Development Fund are only the Members of Parliament who are in the Executive Government no more nor less.”

Grant Wyeth, a political analyst wrote in The Diplomat that “there is a sense that the benefits from large projects that stem from Chinese demand or investment are not being equally distributed, and that the processes that decide on these projects are not transparent. This is creating a strong public sense of suspicion toward the central government — and toward China as well.” In contrast, Taiwan appears to have distributed its aid more directly and more evenly. Powles, at the time “the switch” happened, said she expected “very human” impacts, with “development programs which have been terminated and jobs which will be lost, students who will have to leave Taiwan immediately, relationships which have been formed and have now been severed.” As a result of “the switch,” over 100 young Solomon Islanders who had been given prestigious scholarships to study at Taiwanese universities immediately lost those scholarships. Writing for The Guardian soon after “the switch,” Edward Cavanough interviewed people, from farmers to parents of students in both Malaita and Honiara who felt Taiwan has been a long-standing presence that made life on the island better. “We will not agree with our government with the shift to China,” said Misak, a farmer in Malaita. “We still maintain our allegiance and support our premier.”

There is also an aversion to China. Some Solomon Islanders are put off by the Chinese who visit the country to provide assistance, finding them “rough and disrespectful” compared to their Taiwanese counterparts. Others are alarmed by China’s ambitions in their country, like its attempt to lease an entire island in the archipelago. Still others are repulsed by China’s disregard for freedom and human rights, including its oppression of religious minorities. Like many other Solomon Islanders, Suidani resents the Chinese government’s authoritarian attitude, which it uses at home and increasingly displays abroad. Writing for The Interpreter, Joseph Foukona, Assistant Professor at the University of Hawaii, noted China’s furious reaction to Suidani referring to Taiwan as a country and displaying Taiwan’s flag in public, and how it accused him of “breaching the sovereignty and territorial integrity of China.” This, Foukana wrote, “reflects how the Chinese state administers order and demands obedience within China – and that it expects the countries it has diplomatic relations with to do the same.”

Like many other Solomon Islanders, Suidani resents the Chinese government’s authoritarian attitude, which it uses at home and increasingly displays abroad.

A similar dynamic plays out in other Pacific Island nations. One Pacific Island state that still recognizes Taiwan instead of China is the Republic of Palau. Located closer to the Philippines, its small population of 18,000 are ethnically Austronesian, and thus close to Taiwanese aborigines. In January, its newly-elected president Surangel Whipps Jr. won against a pro-Beijing candidate and was very critical of China. He said his country should be “the last man standing” on Taiwan’s side and denounced Beijing’s attempts to pressure him: “I’ve had meetings with them and the first thing they said to me before […] was ‘What you’re doing is illegal, recognizing Taiwan is illegal, you need to stop it’ […] that’s the tone they use. We shouldn’t be told we can’t be friends with so and so.”

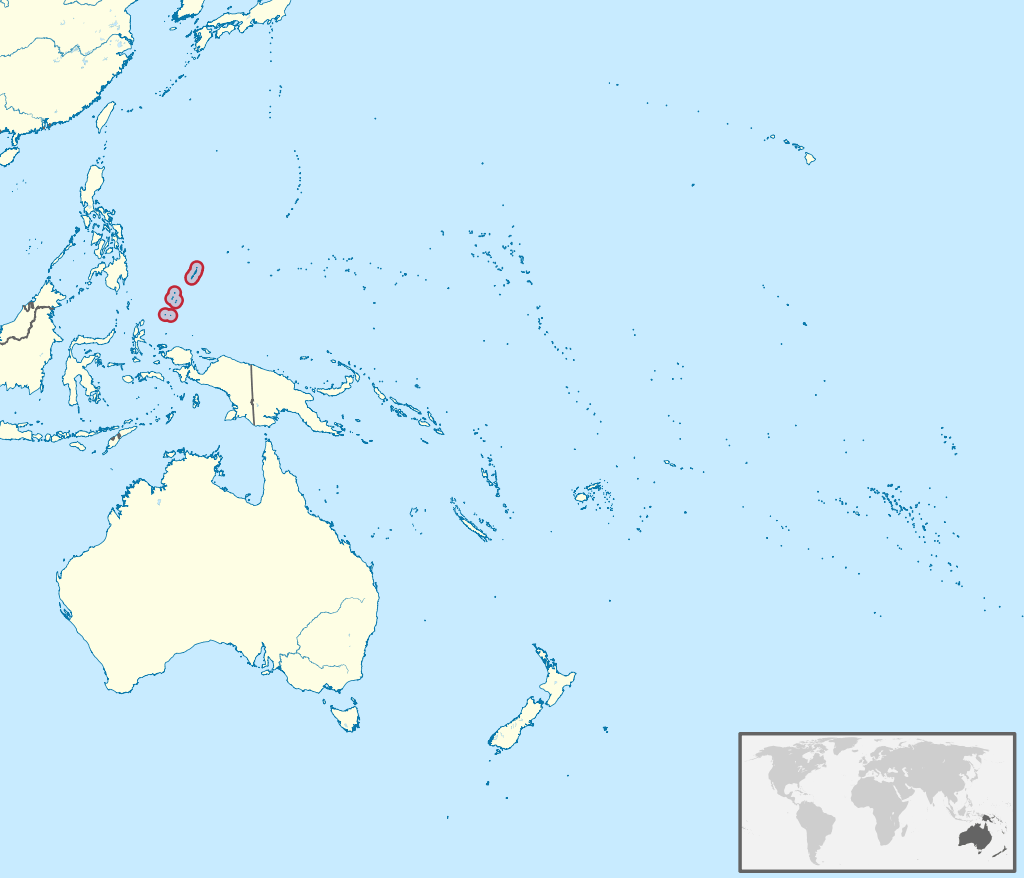

Map showing Palau (Picture Credit: TUBS)

Whipps also described how China suddenly started sending large numbers of tourists to Palau in the early 2010s, before abruptly banning them in 2017 in an attempt to create economic pain. This backfired however: in 2018, writing for The Guardian, Kate Lyons reported how the arrival of Chinese tourists created inflation and skyrocketing rent and food prices – their eventual ban was “a blessing in disguise” – and already in 2015 the Palauan government was trying to reduce the number of Chinese charter flights “in response to environmental and social concerns.”

Pacific Island nations have long been ignored by most of the rest of the world. As a result, many of them are even poorer than countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Until recently, the United States did not see these islands as strategically important anymore and barely paid them any attention. Australia has been criticized for neglecting its historical relationship with Pacific islanders, despite its close relationship with them, something that dates back from the time when Australia was the British Empire’s primary outpost in the Pacific region. This neglect has left room for other powers, like China, to step in with bags of money to fill the gap.

Children in Malaita (Picture Credit: Leocadio Sebastian)

But as tensions rise between China and the West, the Pacific is becoming increasingly strategically important. When the Solomon Islands switched recognition from Taiwan to China, its neighbor Kiribati did the same. Located further north, Kiribati is an archipelago spread across a much larger area, giving it a gigantic exclusive economic zone of 3.5 million square kilometers. In April 2021, China announced plans to restore a former WWII airstrip on one of Kiribati’s northeast islands. The United States used this island, Kanton, for space and missile tracking operations in the past. If China were to militarize Kanton efficiently, it would have a base just 3,000 kilometers south of Hawaii. The Solomon Islands lie close to Australia, New Zealand, and New Caledonia; roughly a third of the way from the Australian coast to Hawaii – if China were to gain a foothold there, it could cut them off from each other.

Globe showing Solomon Islands (Picture Credit: TUBS)

Analysts do not expect Sogavare to resign because of the riots in the Solomon Islands, but opposition leader Matthew Wade has stated that if he were to replace Sogavare, he “would go back to the people” and hold a referendum on whether China or Taiwan should be recognized. The riots seem to have died down now, but, whatever the case, the tussle between China and the free world for influence in this region is sure to continue.

Related posts: