The Subversive History of Japanese Tattoos

By B. Alexandra Szerlip

Contributor

2/7/2019

According to a 2018 Newsweek magazine survey, Italy ranks first in the Western world for being home to adults who sport tattoos (as many as four per person) – at 48% of the population. Sweden ranks a close second. The United States ranks third – we’re talking about an estimated 45 million people. From there, in descending order: Australia, Argentina, Spain, Denmark, the UK, Brazil, France, Germany, then Greece.

The numbers are considerably lower in Asia, where skin decoration still carries the onus of a centuries-long association with criminality and the lower classes — sailors, “primitives,” sideshow performers, gamblers, pirates, thugs, and gangsters.

But in fact, some of the most stunning tattoos ever created — anywhere — pay homage to the art’s spiritual homeland.

As early as the 17th century, Japanese authorities had adopted the common Chinese practice of using tattoos as a form punishment and identification of thieves and other “minor” lawbreakers. Simple geometrics were drawn in black ink on arms, wrists, ankles, and sometimes faces, then driven in with a series of needles attached to a handle.

During the 18th century, tattoos were commandeered as proof of amorous devotion. Courtesans of uyiko-e, Edo’s pleasure district, sometimes had the name of a favorite client tattooed on their upper arm. On occasion, a besotted client might do likewise. Several extant woodblock prints document this practice; one by Utagawa Kunisada (from his series On Contemporary Beauties) depicts a young woman, whose affair has clearly soured, biting down on a handkerchief to keep from screaming as a friend burns the tattoo off with hot pellets.

Picture Credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Larger tattoos eventually became fashionable among young, trendy, big-city males. Though samurai had rarely, if ever, sported body designs, images of dragons, demons, severed heads, and bloody corpses — romanticized throwbacks to this medieval soldier caste — were much in favor.

Scholars believe that the fad would have gone the way of all fads had it not been for the immense popularity of Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Water Margins, a series of lush, colorful, dynamically action-filled woodblock prints that first appeared in 1827. Also known as One Hundred and Eight Heroes, Water Margins was based on a translation of a 14th-century Chinese text (based, in turn, on 12th-century stories) about heroic, Robin Hood-like bandits dedicated to protecting ordinary citizens from corrupt officials.

In the original Chinese version, only four of the superhuman “heroes” (notably Shi Jin, described as having nine dragons gracefully swirling around his torso) had tattoos. (Confucian piety, not to mention Christianity and Judaism, frowns on altering one’s God-given body.) With a flair for creative license, Kuniyoshi created elaborate skin decorations ranging from peonies and nine-tailed kitsune foxes, octopi and squid, to fierce hawks, crouching tigers, swooping eagles, and cowering monkeys – for 11 more of the heroes.

Shi Jin

The son of a silk dyer, Kuniyoshi had grown up surrounded by rich colors and patterns. At 14, his drawing talents got him admitted, as an apprentice, to the studio of famous ukiyo-e print master Utagawa Toyokuni. Toyokuni’s speciality was portraits of Kabuki actors. It was a relationship that would bear remarkable fruit.

Despite the fact that Water Margins’ bandit heroes acted outside the law, the book was deemed educational and morally appropriate. Kuniyoshi — fundamentally rebellious, in addition to being highly skilled — had cleverly circumvented the government’s watchful eye by choosing to romanticize (and Japan-esize) 12th-century folk heroes. By covering his bandits with decoration as dazzling and ambitious as those found on the finest kimonos (it’s often difficult to tell where the kimono motifs end and the tattoos begin), Kuniyoshi’s prints managed to promote the exotic while hinting at the illicit. Also a political satirist, he used animals and plants as visual allegories which, though apparently subtle enough to elude the shogunate’s radar, weren’t lost on the public.

Kuniyoshi’s prints managed to promote the exotic while hinting at the illicit.

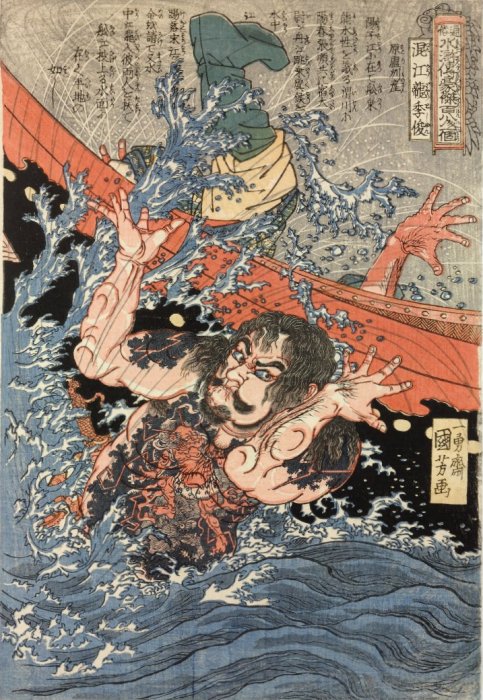

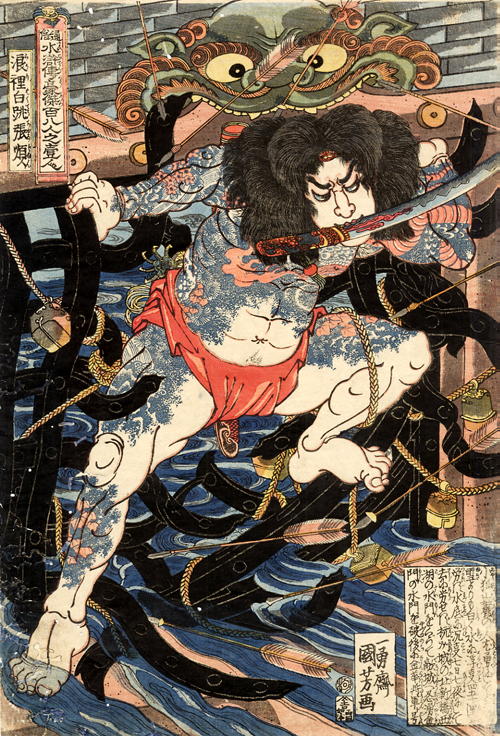

The bandit Zhang Shun’s arms, chest and calves were covered with an enormous snake slithering through ivy near a mountain waterfall (Zhang Shun was a strong swimmer, often stripped down to a loincloth). Similarly, Kuniyoshi gave Ran Xiaowu, a fisherman-turned-smuggler, an underwater fight scene that showed off his fierce, indigo-colored leopard torso.

Zhang Shun

Another Water Margin hero was Li Jun, whose body serves as a canvas for a portrait of Raijin, the Thunder God, surrounded by lightning bolts. A waterfall cascades down Du Sing’s ample back while a dragon ripples across his forearms. Kuniyoshi covered the notoriously handsome bandit-martial artist Yan Qing with lions, peonies, and a waterfall

Woodblock prints were a complicated business. First came the drawing, which is carved into wood blocks, then printed. In the early 18th century, they were hand colored. In 1765, a full color process was perfected, using a different block for each of five or more colors, each of which had to be perfectly aligned. Still, having been mass-produced, a print could be had for the price of a bowl of noodles. Those who could afford to often used them to paper the walls of their homes.

It wasn’t long before Kuniyoshi’s designs became the basis of actual tattoos. The success of Water Margins propelled Kuniyoshi to rock star status, fueling the popularity of warrior figures, which in turn inspired a craze for the colorful, ornate designs being applied to human skin. These were especially impressive considering the added complication of working on three-dimensional, breathing “canvas,” plus the relatively primitive tools that Edo practitioners had to work with. (Kuniyoshi, known as “scarlet skin” to his friends, reputedly had a tattoo that began at one shoulder and traveled down the length of his back.)

The tattoo surge proved particularly popular with manual laborers — construction workers, porters, horse grooms, palanquin and rickshaw drivers, carpenters, and couriers — men whose work, not coincidentally, often allowed them to doff their clothes in public.

Edo (now Tokyo), having been built largely of wood, was hugely dependent on its firefighters. Given that dragons (which live in both air and water) were believed to control weather and send rain, kumonryu (dragon tattoos) were a favored design among these brave public servants. (Dragons also represent the warrior spirit.) The heavy quilted and hooded clothing they wore, which would be soaked with water for added protection, featured similar designs.

California-based tattoo artist Don Ed Hardy, who studied with Japanese master Horihide in the 1970s, wrote that firemen “would strip bare before approaching the conflagration. The intent, besides ease of movement, was to strike a dashing pose and ‘outcool’ the rival brigades fighting the blaze.”

Firemen “would strip bare before approaching the conflagration.”

***

In 1842, concerned about social unrest, and with the shogun’s iron grip beginning to loosen, the Japanese government clamped down on depictions of current politicians and military figures in woodblock prints, placing restrictions on the size, and even the colors, used in the prints. Shunga (woodblock erotica) was outlawed altogether as a threat to public morality.

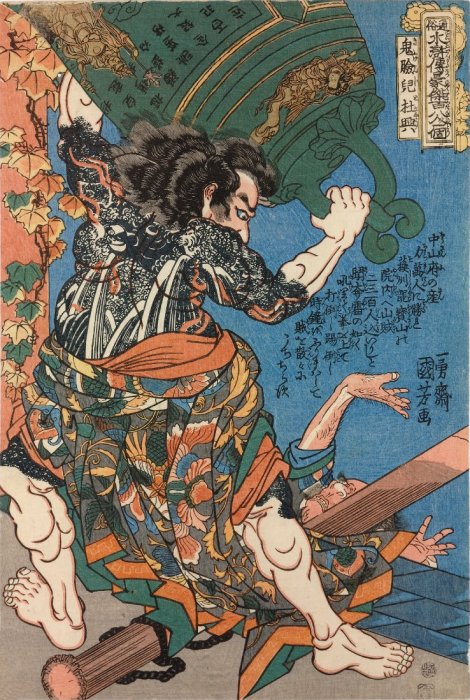

Meanwhile, the work of Kuniyoshi, and several of his contemporaries, had infiltrated and greatly informed Kabuki theatre, thereby further disseminating – and glorifying – the art form. Kabuki’s tattooed heroes were often otokodate — flamboyant, low-born “street knights,” like those in Water Margins, with whom the common citizenry could identify. Their rivalry with hostile samurai formed the plots of many plays. We know this because the most famous performances and performers of the day were immortalized in subsequent woodblock portraits by some of the era’s finest artists. (Kuniyoshi had followed up his initial success with another series, featuring 800 heavily-tattooed historical heroes (Honcho Suikoden Goyu Happyakunin), further promoting body decoration.)

Needless to say, actors didn’t limit their repertoires by subjecting themselves to getting actual tattoos of a particular character. They either painted their bodies or wore tightly fitted cotton or silk printed body suits – very effective for performances by candlelight.

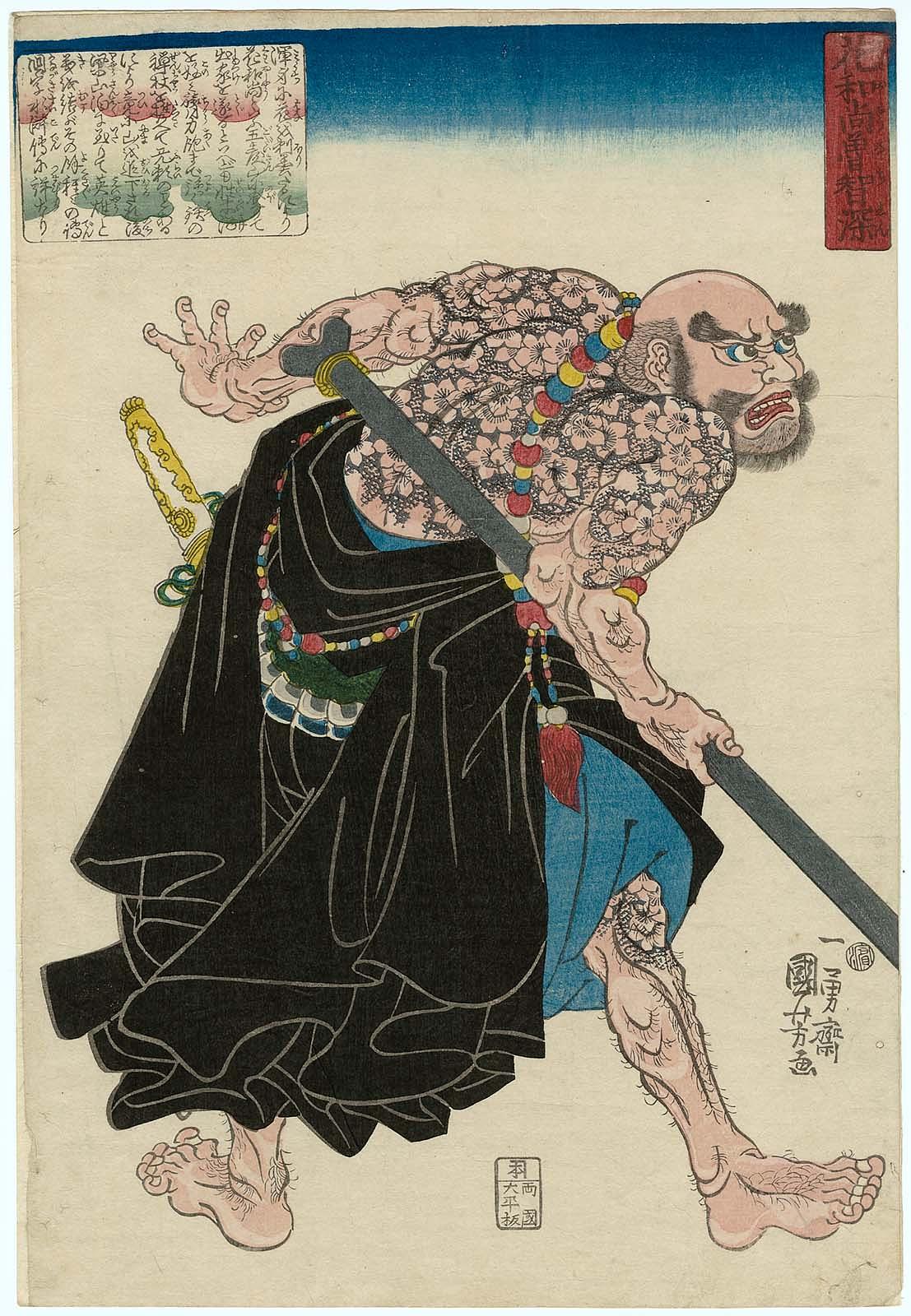

An actor portraying the bandit hero Ruan Xiao’er sports a large lobster stretching up the length of his arm, and a feathered phoenix on his chest and shoulder. Another famous bandit is decorated with a detailed rendering of the pot-bellied Chinese hero Wu Song killing a tiger with his bare hands. The character Shi Jin (recognizably portrayed in the woodblock print by Kabuki actor Nozarashi Gosuke) has a dragon encircling his right arm. Army officer-turned-outlaw-turned- priest Lu Zhishen (gorgeously rendered by Utagawa Kunisada) is covered in a mass of delicate cherry blossoms, which contrasts with his brawny physique.

Lu Zhishen

Cherry blossoms (sakura), like tattoos, exemplify the Japanese idea of mono no aware: that beauty is ephemeral, transient. That life, like beauty, is fragile and therefore all the more precious. These delicate flowers, which bloom for a very short time, are also a traditional metaphor for warriors who die young.

***

In 1868, the new Meiji government took power. Japan was slowly “opening up” to the wider world. In an attempt to “modernize,” and concerned about being seen as “barbaric” in Western eyes, the country outlawed tattooing altogether (along with Buddhist cremations). Police raided tattoo masters’ workshops, seized equipment and destroyed decades-worth of “pattern books.”

Another theory about the governmental backlash points to the centuries-old edict that only the highest members of society (the royal family and its top advisers) could wear richly embroidered clothing. Elaborate tattoos were a way of circumventing those laws and defying the established social order.

Which brings us to the Yakuza who, from the start, embraced tattooing as a “signature.” Their name stems from an Edo-era card game in which a particular losing hand was known as ya-ku-za. As gambling was illegal in ancient Japan, the connotation was of undesirables, outsiders, “losers.”

Yakuza consider themselves a patriotic cross between samurai warriors and Water Margin bandits, with a touch of ninja thrown in. Tattoos, for them, serve multiple purposes. They emphasize the Yakuzas’ difference from the “normal” world, their tolerance for pain, and their solidarity. They offer symbolic protection from harm and symbolic ties to a romanticized past. Carp tattoos (it’s believed they swim upstream in the hope of becoming dragons) are indelible reminders of endurance and courage. Last but not least, tattoos are dignified adornments unique to each man, unmatched by the finest clothing or jewelry.

Traditionally, Yazuka come from poor, or troubled, backgrounds; many are school dropouts. Membership offers discipline, community, and purpose, a social order of its own. It’s not uncommon to spend two to 10 years (and considerable yen) acquiring a full-body tattoo (stopping at the neck, wrist and ankles in order to be hidden under clothing), with the middle of the chest left unadorned so that kimonos can be worn without risk of exposure. Popular Yakuza designs include the aforementioned carp, dragons, thunderbolts, gods of good fortune, and…Kuniyoshi-inspired bandits.

***

To the consternation of the incredulous Meiji lawmakers, visiting foreigners were fascinated by the country’s ornate body art. Embassies even made a point of hiring heavily tattooed porters and grooms to pull their rickshaws.

Begrudgingly, former laws were loosened, allowing tattoo shops in port cities to remain open as long as they catered only to non-Asians. Patrons soon included the future Czar Nicholas II of Russia and his cousin, future King George V of England.

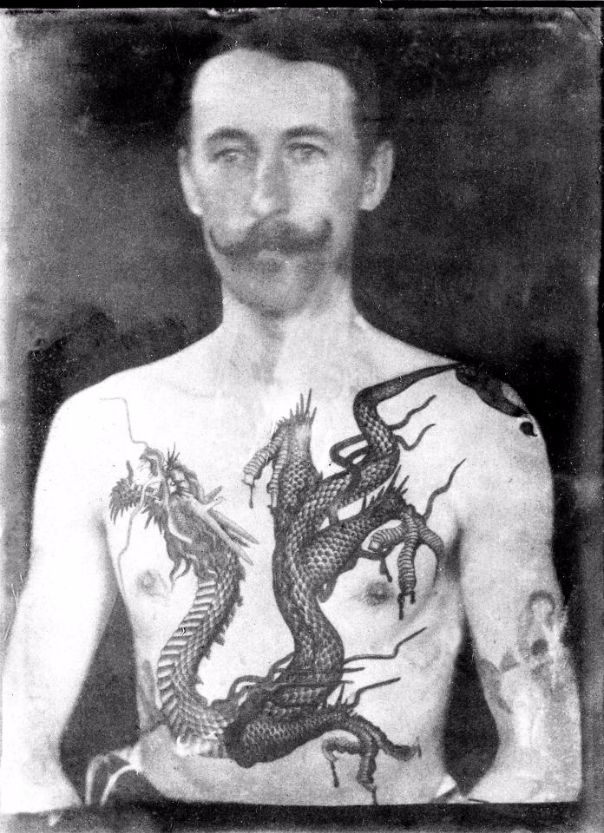

Adding to the list of “decorated” crowned heads – though many obtained their tattoos outside of Japan – were King Edward VII, King Frederick IX of Denmark, Kaiser Wilhelm, Alfonso XIII of Spain, King Oscar of Sweden, Queen Victoria’s favorite nephew, Winston Churchill’s mother (a snake circling her wrist), and an untold number of Indian potentates. King George of Greece opted for a five-colored, Japanese-like, flying dragon covering his chest; its elaborately shaded and feathered wings took 80 hours to complete.

Tattooed Victorian man

***

After World War II, tattooing became legal in Japan (in the name of freedom of expression), but the stigma of criminality remains. The popularity of 1970s movies featuring coldblooded, heavily tattooed Yazuka didn’t help.

According to a 2018 article in the Washington Post, “Visitors to Japan who have tattoos bigger than a Band-Aid can forget about going to hot springs or swimming in a public pool…some beaches and gyms, certain restaurants and karaoke rooms, and even some convenience stores.” Those who do risk being viewed “with repugnance.”

In 2012, Osaka’s City Hall made a controversial decision to ban tattoos amongst its employees, under the premise that they intimidated the general public. Employees who already had them were required to keep them covered at all times and forbidden to get more. Then, in 2015, Osaka’s police embarked on high-profile raids on tattoo artists, claiming they could only practice if they had health care provider licenses. In other words, if they were doctors.

Last November, thanks to the tireless efforts of a group called Saving Tattoos in Japan, the Osaka High Court issued a landmark decision: tattooing is artistic creation, not medical practice. Requiring medical licenses violates Constitutional rights.

Meanwhile, tattoos continue to grow in popularity worldwide. Tattooing has, in fact, become an extremely competitive profession. Though styles change, Kuniyoshi’s designs continue to be replicated, nearly two centuries later, both in Japan and beyond. Water Margin stories, in their various iterations, inform everything from tv shows and films to comic books and video games.

Tattooists, like sushi chefs, have been traditionally, and exclusively, male. As with many such die-hard constructs, this, too, is slowly changing. One of Japan’s first top-ranking female tattoo artists is Shodai Hori Nami, whose rise through the ranks is even more impressive considering that she trained prior to the introduction of electric tools. Her designs are noteworthy both for meticulous draftsmanship and exuberant color. “You can endlessly tell me to go play golf,” she said, in answer to an interview question about married women knowing their place, and the difficulty of the path she chose, “but I’m not interested.” (For the record, at least one 19th century woodblock print depicts female Kabuki warriors. Toyohara Kunichika created a triptych of elaborately tattooed Amazons, 10 in all, preparing for battle, brandishing swords, pole weapons…and hair combs.)

Elsewhere, from Amsterdam to Los Angeles, there’s a new generation of female tattoo artists. The latest craze appears to be “embroidery tats” — designs that mimic embroidery stitches and appear to be three-dimensional. (Check out the more than 2,000 hashtags on Instagram.)

The Washington Post may have overstated its point. Japanese try to be non-confrontational, and foreigners (decorated or otherwise) are treated differently from Yakuza. Still, it will be interesting to see what happens when Japan hosts the 2020 Summer Olympics when both international guests (an estimated 40 million) and athletes will, inevitably, be showing some skin.