The Todai Mystique

By Richard Milner

Staff Writer

25/11/2019

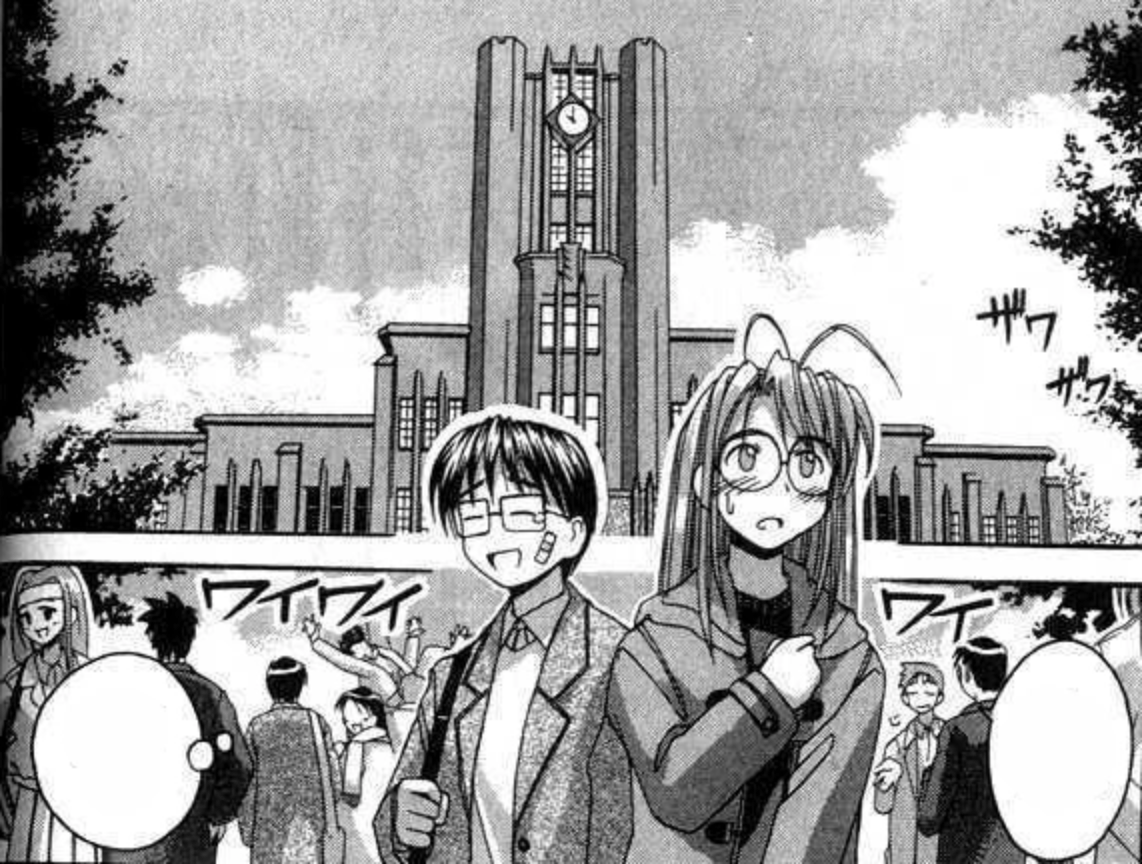

The iconic clock tower at the Yasuda Auditorium

The popular anime Death Note follows the cat-and-mouse game between genius high school serial killer Light and genius detective L. When Light takes the entrance exam to enter Tokyo University, L (suspecting Light) does the same so he can keep a closer eye on him (they both attain the highest score in the entrance exam). The manga Tokyo Daigaku Monogatari (Tokyo University Story) follows the romance between two high school students preparing to apply to Tokyo University. In the manga Dragon Zakura, a former biker attempts to do the impossible: get five hopeless students from a crappy high school into Tokyo University. The popular manga (and later anime) Love Hina spans 14 books. Most of it is about the struggle of Keitaro, a loser with middling grades hell-bent on getting into Tokyo University, despite already having failed the entrance exam twice. Through a twist of events, he ends up becoming the manager of a dormitory for girls, most of whom also dream of studying at Tokyo University. In Itazura na Kiss the brilliant Naoki is a shoo-in for Tokyo University, but surprises everyone by choosing to matriculate elsewhere so he can be schoolmates with his love interest, Kotoko.

Thus is the status of Tokyo University (or Todai, as it’s known in Japan) embedded in the Japanese psyche as the country’s premier university: brilliant people go there, or are expected to go there, and people who want to be thought brilliant aspire to go there (whether realistically or not). In Japanese society, Todai is the Holy Grail; if you could combine Oxford and Cambridge in the UK or Harvard and Yale in the US, you may get an idea of its cultural significance. In April this year, the Budokan, a stadium in Tokyo with a capacity of 60,000, was booked out for the 6,000 or so students, their families, and the press, attending Todai’s opening ceremonies. To put this into perspective, this would be like Cambridge renting out Wembley Stadium for the day, or Princeton renting out Madison Square Garden.

In Japanese society, Todai is the Holy Grail; if you could combine Oxford and Cambridge in the UK or Harvard and Yale in the US, you may get an idea of its cultural significance.

After this event, new students often make their way to Akamon, the iconic red gate at the main Hongo campus, and pass under its ruddy halo to sear away their old, pre-university existences and assume their newly deified forms. Todai, it’s clear, is more than just a university – it’s one of Japan’s most storied institutions.

Akamon

***

Founded in 1877 by the Meiji government as Japan’s first national university, Todai was supposed to help usher Japan into the modern world so it could compete with the Western powers. The original Todai campus, the current Komaba campus, was cobbled together from existing vocational schools and originally called the Imperial University.

Sketch of the old Faculty of Law building in 1902, before it was destroyed in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake

But how does one get into Todai? Acceptance into its hallowed halls depends almost completely on passing a series of exams. First, there’s the generic, comparatively easy national exam, the results of which can be used to apply to a number of universities in the country, and then there’s Todai’s legendarily difficult entrance exam. Passing these exams determines whether someone will be accepted into Todai; everything else, school grades, extra-curricular activities, are practically meaningless. (Todai does have an alternative, more holistic admissions process, the Admission Office Exam, wherein students use personal statements, reference letters, interviews, and presentations to panels of Todai faculty to apply, but this was only instituted in 2015, and only a tiny minority of students enter the school this way (2.3% this year).)

Students applying to Todai must apply directly for one of three concentrations derived from the two broad categories of Arts and Sciences. The Arts is divided into Economics, Law, and Literature and Education. The Sciences is divided into Engineering and Mathematics, Agriculture and Pharmacology, and Medicine. Performance on the entrance exam is weighted according to which of these three concentrations the student intends to focus on.

General Library

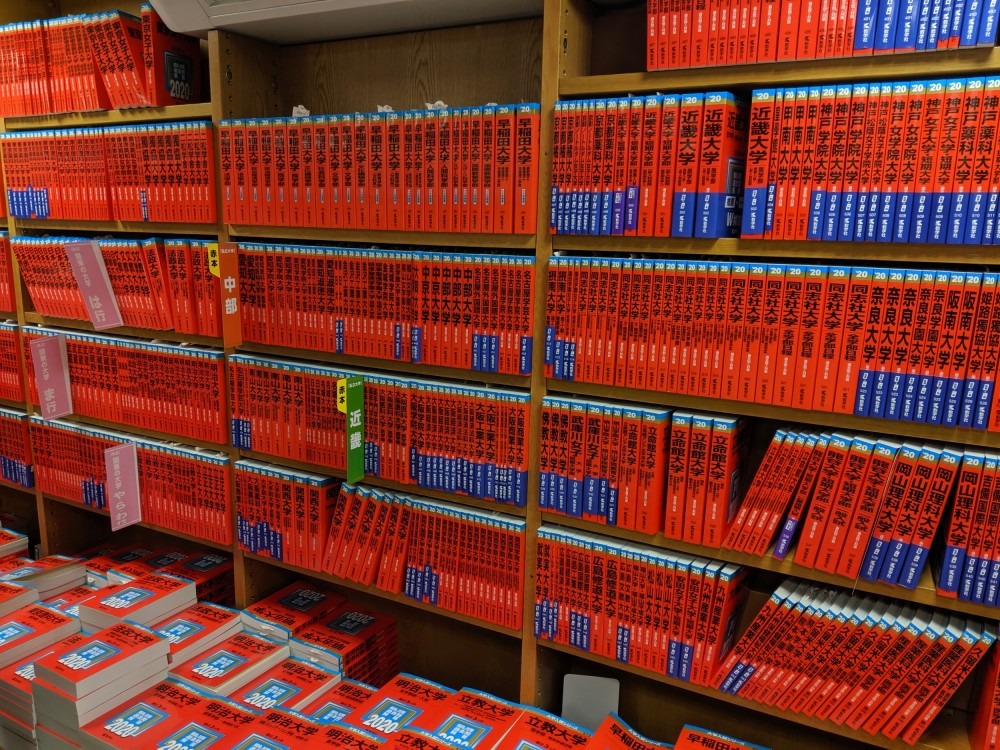

Naturally, a whole industry has evolved around getting students into Todai. If Todai is intellectual heaven, then the Bible is the akahon (red book) study guides, which are divided into Arts and Sciences and contain past entrance exams. A perusal of the past papers reveals English essays comparable to those in the SATs (i.e. American high school level) and calculus-level math problems. Then there are Todai-specific cram schools (the Japanese equivalent of prep schools), with classes that typically commence at 3:15 pm and can run till 10 pm, and cost up to $3,000 a year per subject for group classes and $4,200 a year per subject for private classes (competitive students will typically start going to cram schools at least a year ahead of the entrance exam, and someone taking the Science paper, for example, would be tested on Math, Physics, Chemistry, and Biology).

Akahon

Compared to its Western counterparts, Todai’s school fees, at $6,000 a year, are very affordable (Oxford charges $11,500 a year, Yale $72,000), and a large proportion of its students come from lower-income households (a third of student families earn just $40,000 a year or less) and to offset costs almost a quarter of students have permanent part-time jobs. Because cram schools are generally located in urban areas, though, students from the countryside are considerably disadvantaged, and 32.9% of Todai students hail from Tokyo alone.

Science is decidedly more popular at Todai than Arts, with 56% of students choosing the former and 44% the latter. Science students are also more likely to stay at Todai for graduate school to become more competitive in the job market, with 79% of them electing to do so, versus 23% of Arts students. Though students are required to pick a concentration when they apply to Todai, for the first two years, they only take general Arts or Science classes – it’s not till their third year that they start studying their actual major (excluding degrees like medicine, undergraduate degrees in Japan usually take four years).

Scene from Love Hina

What will the elect find when they finally arrive at Todai? A university virtually identical to any other in Japan or the West. Gray-carpeted classrooms with projectors; white linoleum floors and sundry stores and Starbucks. Todai student life is highly insular. Students stay tethered to classmates of the same grade and adhere to routines as closely as they slip into the passive, rote-learning common to public universities in Japan. Early-year students have schedules filled with classes and assignments, whilst latter-year students have large gaps in their schedules between midterms and finals meant to be spent working on theses orchestrated by departmental advisors. Students in the sciences do little more than spend 12 hours a day in a lab with their cohorts carrying out the wishes of professors who allocate generational projects from one set of graduates to the next.

This rigidity fits nicely with the studious image of Todai students that rests in the mind of the general public. However, the sharp divide between sciences and arts is reflected in their respective campuses. Most of Todai’s maintenance budget goes into its sciencey Hongo campus, the well-manicured main campus that usually appears in pictures. Student life there, however, is largely inert, with students shuffling from one building to another with little interaction in between. The artsy Komaba campus, however, sits in an undeveloped residential neighborhood and is falling into visible disrepair. Grass is knee-high, buildings are chained off, and courtyards are overrun with pavement-splitting bushes and wall-climbing ivy. Yet the tenor there is downright lively. Students linger in aimless groups, lie on benches, practice hip-hop dance, just like at any Western university.

Building on Komaba campus

Most professors at Todai are Todai graduates themselves, and many have studied abroad, won awards in their fields, and have numerous publications to their name. They head up research projects, both small and large, across private and public sectors totaling roughly $540 million last year. This research includes ventures like an ocean-bound laboratory that analyzes fish DNA to better understand marine food chains, the development of a fluorescent reagent that helps detect prostate cancer, the role of AI in sustainable agriculture, and an optical lattice clock that apparently loses only 1 second every 30 million years.

For all its hype, though, Todai simply recreates the rigid, hierarchical structures in Japanese society, including the kohai (young mentee) – senpai (respected elder) dynamic. This can be seen in student-professor relationships at Todai. These relationships can be close, even chummy. However, students are keenly aware that professors are the first point of contact to the cadre of Todai allies that students encounter after graduation. Job opportunities in Japan often come from word-of-mouth referrals that can include having attended the same junior high school, and, because of its status, Todai’s name commands a level of favoritism beyond all others. Under the guidance of their professors, Todai students approaching graduation reap the rewards of their hard work – not so much in the form of a better education, but in connections between alums and affiliates who form Todai’s tribal network of alliances. The lesson here is clear: to progress to the next level, follow your senpai’s lead. Though it was founded to help modernize Japan, Todai teaches its students less how to change things by thinking critically or independently than how to fit into Japanese society and carry on the traditions of the past.

***

Where do Todai graduates go when they complete their studies, though?

A third of arts graduates go on to work at one of Japan’s ministries, like the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, the Ministry of Economy and Trade and Industry, or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The rest of them often join banks like Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation or Mizuho. Science graduates commonly join the manufacturing, energy, or IT fields, including companies like Sony and Toyota, or consultancies like Accenture.

There is one place that hires the largest number of Todai graduates, regardless of field of study, though, and that’s the sprawling Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism. So many Todai graduates join this one ministry, in fact, that it accounts for approximately 15% of all Todai graduate hires per year (nearly 100).

Todai graduates have won numerous Nobel Prizes in the fields of Literature, Physics, and Medicine, as well as Pritzker Architecture Prizes. They’ve also gone on to become astronauts, like Takuya Onishi, and captains of industry, like Kouei Tsuge, chairman of JR Tokai, Japan’s railway system. Some have become influencers or entertainers, like Osamu Hayashi, a celebrity educator, or TV host Rei Kikukawa.

Rei Kikukawa

17 of Japan’s 65 Prime Ministers have graduated from Todai. Eisaku Sato won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1974 for entering Japan into the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, while Yasuhiro Nakasone revered military power and was an adherent of the philosophy of nihonjinron (Japanese exceptionalism). Some made important contributions to Japan’s economy (Kiichi Miyazawa), or social welfare (Yukio Hatayomo); some, like Takeo Fukuda, were just lame ducks.

Yasuhiro Nakasone (second from left)

Some were less successful, or downright shady. Kenji Kasahara founded an online social network called Mixi, that was popular in the late 2000s, but which has since gone defunct. Takafumi Horie (dubbed Horiemon for his resemblance to the Japanese cartoon character Doraemon) was released from jail in 2013 after being incarcerated for securities fraud related to Livedoor, an internet services provider taken down in 2006.

The vast majority of Todai graduates, however, become die-cast worker drones. Todai students are all intelligent, or at least intelligent enough once augmented by cram school training. It’s likely, though, that the truly exceptional graduates would have been exceptional whatever school they attended. Conversely, when its more mediocre graduates gain a measure of prominence, it’s usually because Todai’s reputation did much of the heavy lifting.

The vast majority of Todai graduates, however, become die-cast worker drones.

Todai’s reputation as the best is undisputed in Japan, and it’s also consistently ranked #1 in the country on international rankings like The World University Rankings, which takes into account factors like reputation, research output, and faculty-to-student ratio. However, in 2019, Todai slipped to #2, in large part due to its low international student count (3.15% of the undergraduate student body, 9% overall), as international diversity makes up 20% of the total score in those rankings.

The university that came in #1 in Japan was Kyoto University (Kyodai), where international students make up 12% of the student body. This was enough for Todai President Makoto Gonokami to declare reforms to focus on globalization and the development of a more multicultural environment. The final goal of updating Todai’s curriculum is not simply to best Kyodai, however, it’s to break into the top 10 universities in the world and sit aside venerated institutions like Oxford (#1), Cambridge (#3), Harvard (#7), and Yale (#8) (Todai is currently #36).

A one-time slip in an international ranking is unlikely to threaten Todai’s preeminent place in the Japanese imagination, of course, but if it wants to be truly world-class, it will have to question the way it’s always done things, and to train its students to question, too. Only then can it be as exceptional as Japanese people think it is.