Who’s Afraid of Peng Shuai?

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

25/11/2021

Peng Shuai at a tennis tournament in Strasbourg in 2014 (Picture Credit: Prachatai)

The most striking thing about the Peng Shuai fiasco is how dumb it all is. The inanity of Peng’s post has been compounded by the Chinese government’s overreaction to it, the ham-handed attempts by state media to whitewash it, and the role the International Olympic Committee has played in this farce, stupidity piled on stupidity, like layers in a demented wedding cake.

Peng Shuai’s post (translated here), which started this whole debacle, is one of the most bizarre things you’ll ever read. Despite some calling it a Me Too sexual assault allegation, it is not exactly what you’d call “damning.” Reading it made me feel worried about Peng’s mental state rather than angry at the man named in it. “I know it’s not clear, and it’s useless to say anything about it,” it begins. “But I still want to say it. I know I’m a hypocrite, I admit that I’m not a good girl. I’m a very bad girl.” This pretty much sets the tone for the rest of the post.

Peng’s post is a rambling, confusing, and often garbled account of what, if true, was a rather screwed up relationship between her and former Chinese Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli. It alleges that the two had an on-again, off-again affair for some years. It alleges that Zhang’s wife knew about it and accepted it, so much so that she ate dinner with her and Zhang and allowed the two to have sex in their house whilst she was home. The whole post is addressed to Zhang and reads like an open letter to him, a cry for attention. It does not read at all like the account of someone who has been sexually assaulted or forced into sex, instead it’s filled with statements like “I discovered that you are a very good person, and you also treated me quite well,” “We had days when we couldn’t stop talking with each other,” and “our feelings had nothing to do with money and power.” It mentions her love for Zhang, expresses admiration at his intelligence and erudition, and recounts their happy times together. It talks about how she was starved for affection as a child. It laments how he made her keep their relationship a secret, how he refused to divorce his wife for her, how she had to suffer insults from his wife when he wasn’t there (exactly how and why Zhang’s wife and mistress would be interacting without Zhang present is unclear).

Former Chinese Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli at the Fortune Global Forum in Chengdu in 2013 (Picture Credit: Fortune Live Media)

It doesn’t even really seem to allege that Zhang sexually assaulted Peng or forced her into sex. It does accuse Zhang of “forcing” her to have sex with him on one occasion in their sporadic relationship, and states that she agreed to do so because she was “afraid” and “panicking” – it’s unclear why she felt this as there is no reference to him using physical force against her (and, indeed, since Peng was 32 and athletic at the time, and Zhang was 72 and not, it’s likely she’s stronger than him) or threatening her in any way – but in the same breath it states that she also agreed to do so because she was “carrying all the feelings I had for you during those 7 years.” Peng herself doesn’t seem to set much store in this; instead her biggest grievance against Zhang appears to be that he repeatedly seduced her and then stopped contacting her (sometimes for years). The whole post screams “I HATE YOU, I LOVE YOU.” “You played with me,” Peng concludes bitterly, “and when you didn’t want me anymore, you discarded me.” This doesn’t sound like a sexual abuse victim crying for justice, it sounds like an obsessive, jilted ex-lover crying for acknowledgement.

Peng Shuai doesn’t sound like a sexual abuse victim crying for justice, she sounds like an obsessive, jilted ex-lover crying for acknowledgement.

In most other countries, this would be salacious fodder for the gossip mill, but little else. Not only is the trail, such as it is, several years cold, Peng states in the post, repeatedly, that she has no evidence of their affair whatsoever, and if Zhang chose to deny it, it would just be a “he said, she said” situation. Furthermore, even if everything in Peng’s post is true, it is unclear what wrongdoing Zhang would be guilty of. It doesn’t seem like Zhang sexually abused her; it doesn’t even seem like he cheated on his wife because of how strangely ok Mrs Zhang appears to be about the whole thing. Zhang’s only crime seems to be not wanting to continue a relationship with Peng. A sex scandal like this would set people gossiping for weeks, but it’s unlikely to outrage them. It’s basically a non-issue, and the obvious course of action for the government would be to do absolutely nothing.

Except, of course, this is the Chinese Communist Party we’re talking about. In the eyes of the Party, its members are answerable to no one save the Party itself. Its high-ranking members are not accountable to ordinary mortals, even if you happen to be one of China’s most famous tennis players and an Olympic athlete. In the eyes of the Party, even relatively minor aspersions against it or its high-ranking members cannot be tolerated, lest they encourage others to come forward with more. In the eyes of the Party, Peng had committed a grievous sin by airing her grievances against Zhang so publicly. And so the Party did what it does best: it overreacted. Not only was Peng Shuai’s post scrubbed from Weibo (where it was posted) within 30 minutes, even searches for her name have been heavily restricted on Chinese sites. Then, Peng mysteriously disappeared from public view, with speculation rife that she’s being detained by the state.

In the eyes of the Party, its members are answerable to no one save the Party itself.

Peng’s disappearance attracted wide attention, both in and outside China. The international tennis community, in particular, rallied around her, with champions like Naomi Osaka, Serena Williams, Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, and Nicolas Mahut speaking out and drawing attention to her plight. The Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), to its credit, has threatened to pull out of China unless the situation is resolved satisfactorily, and has refused to be cozened by the Chinese government’s propaganda efforts. Before long, foreign governments were voicing their concern and demanding proof of Peng’s safety and whereabouts.

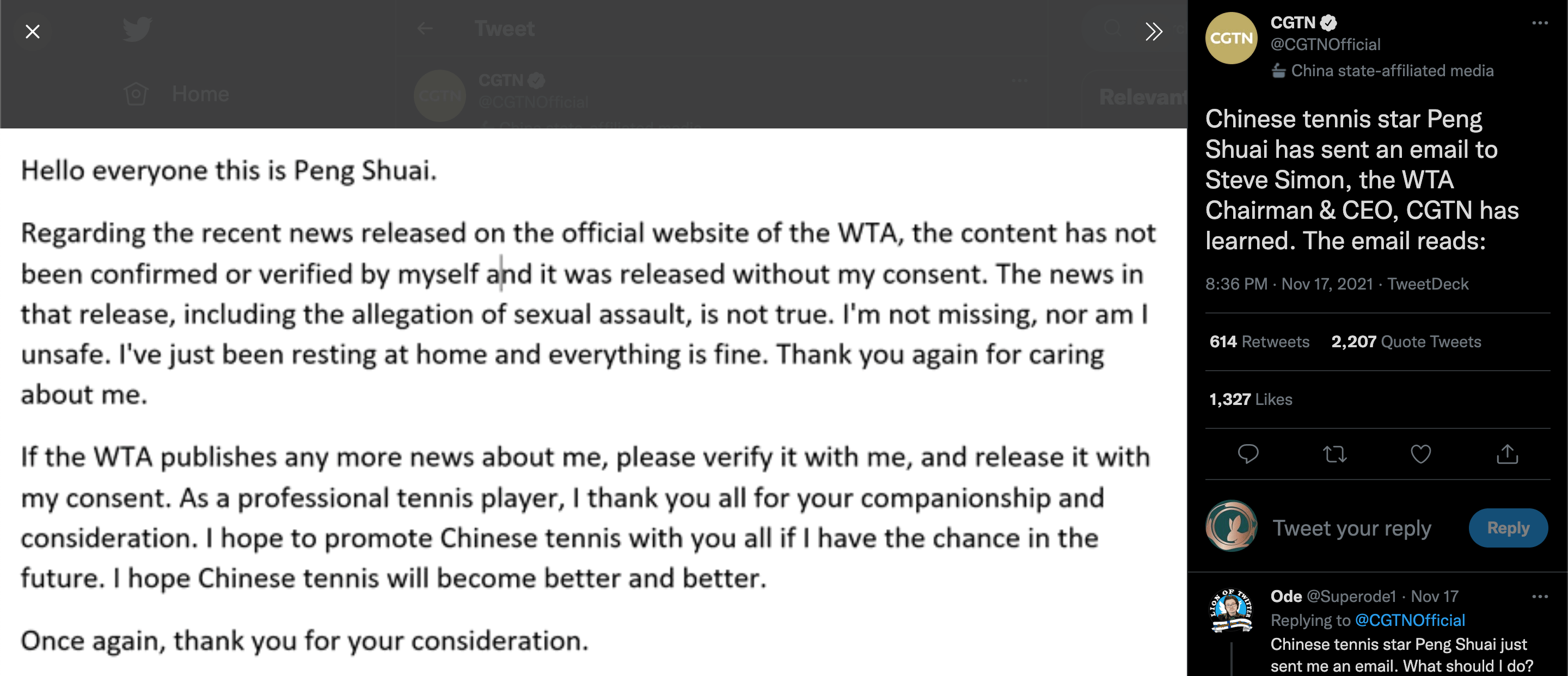

The Party responded to this mounting pressure in its characteristically stupid way – with a propaganda blitz that predictably made it look even more repressive than it already did. It got Chinese state media and its pet “journalists” to share photos and videos purporting to show Peng at a youth tennis event and eating at a restaurant, though there is, of course, no way to know if she is actually free or if she resumed her captivity after being trotted out for that photo op, or, in the case of the former, when these photos and videos were even taken. Most ridiculous of all, state mouthpiece CGTN shared what it claimed was a screenshot from an email Peng Shuai sent to Steve Simon, the chairman of the WTA. In it, the person purporting to be Peng Shuai reassures him that “I’m not missing, nor am I unsafe. I’ve just been resting at home and everything is fine,” before requesting that the WTA obtain her consent before publishing anything else about her. Incredibly, even though it’s presumably addressed just to Simon, it begins with the words “Hello everyone this is Peng Shuai,” and a vertical bar, as if from a blinking cursor, can clearly be seen running through one of the words in this screenshot – as if it’s not from a sent email at all, but from an email or a document that’s still being drafted. This obviously reassured no one, least of all Simon, who said that it “only raises my concerns as to her safety.”

CGTN’s tweet sharing what it claims is Peng Shuai’s email to Steve Simon. Note the cursor mark through the word “and.”

Pretty much the only one who seems satisfied with the way China has handled this issue is the International Olympic Committee, which announced that Peng was “safe and well, living at her home in Beijing, but would like to have her privacy respected at this time,” after holding a video call with her last Sunday. Of course, even a prisoner in a cell can be “safe and well,” and the IOC had no way of ascertaining if Peng was actually free, and so it was heavily criticized for helping China keep up this farce. “Frankly, it is shameful to see the IOC participating in this Chinese government’s charade that everything is fine and normal for Peng Shuai,” said Elaine Pearson, the Australia director of Human Rights Watch. “Clearly it is not, otherwise why would the Chinese government be censoring Peng Shuai from the internet in China and not letting her speak freely to media or the public.” (Honestly, under the circumstances, the only thing now that would definitively prove that Peng Shuai is really free is if she was to travel to a country that has no extradition treaty with China and was then willing to return home.) Since then, the Chinese government has been hard at work with a dual strategy – in China it censors all mention of the Peng fiasco and pretends that it doesn’t exist; abroad, where it can’t do this, it has its diplomats and state media proxies claim that Peng is free and that this whole thing has been “maliciously hyped-up.” This contradiction, though, has only made it look even more absurd. As one comment on Weibo noted before it was removed, Peng’s case is “prohibited in China – you’re not allowed to discuss it – yet the Chinese government is busy explaining it to foreigners.”

“When you tear out a man’s tongue, you are not proving him a liar,” says Tyrion Lannister in George R. R. Martin’s A Clash of Kings, “you’re only telling the world that you fear what he might say.” This is a simple lesson, but one the Chinese Communist Party seems incapable of learning. What’s been the result of the Party’s overreaction to Peng Shuai’s post? Peng’s grievances, which were really rather minor, and which would have soon faded away by themselves, have now been amplified into every corner of the planet. The issue of Zhang never calling Peng back has now grown into the vastly more serious one of the Chinese government persecuting Peng for posting about it. China’s state media has never looked more blatantly like a propaganda mouthpiece, and the IOC now looks like either an amoral gold digger or a dupe at a Potemkin village for going along with this charade. People in China, and the rest of the world, have yet another reason to distrust the Chinese government. The Party is, once again, the victim of its own brutishness, paranoia, and control-freakery. It was afraid of looking bad, so now it looks worse. It couldn’t stand to have a small problem, so now it has a big problem. It would be funny if it wasn’t so awful.