Why Authoritarians Like Taking Down Celebrities

By Asavari Singh

Contributor

12/11/2021

Aryan Khan (Picture Credit: Hina Bibi)

Aryan Khan is the eldest son of the Bollywood megastar Shah Rukh Khan. The 23-year-old’s tousled hair plumes up from his broad forehead just so. His golden skin hints at breakfasts on sun-kissed terraces, his chiseled body at long sessions with a personal trainer. His style is what the women’s magazines call effortless, and they are right since his good genes and expensive wardrobe never required any effort from him at all. His pouty-lipped face is beautiful, but it’s the kind you might find yourself wanting to slap.

On 2 October, the little prince was gearing up for a big weekend on a luxurious cruise ship, which offered burlesque performances, whiskey-tastings, and a rave party. But also onboard the ship were undercover agents of the narcotics control bureau. By the time the night was over, the officers, weirdly accompanied by a functionary of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had confiscated 13 grams of cocaine, 22 MDMA pills, and 21 grams of marijuana, and arrested eight people. Aryan Khan was among them.

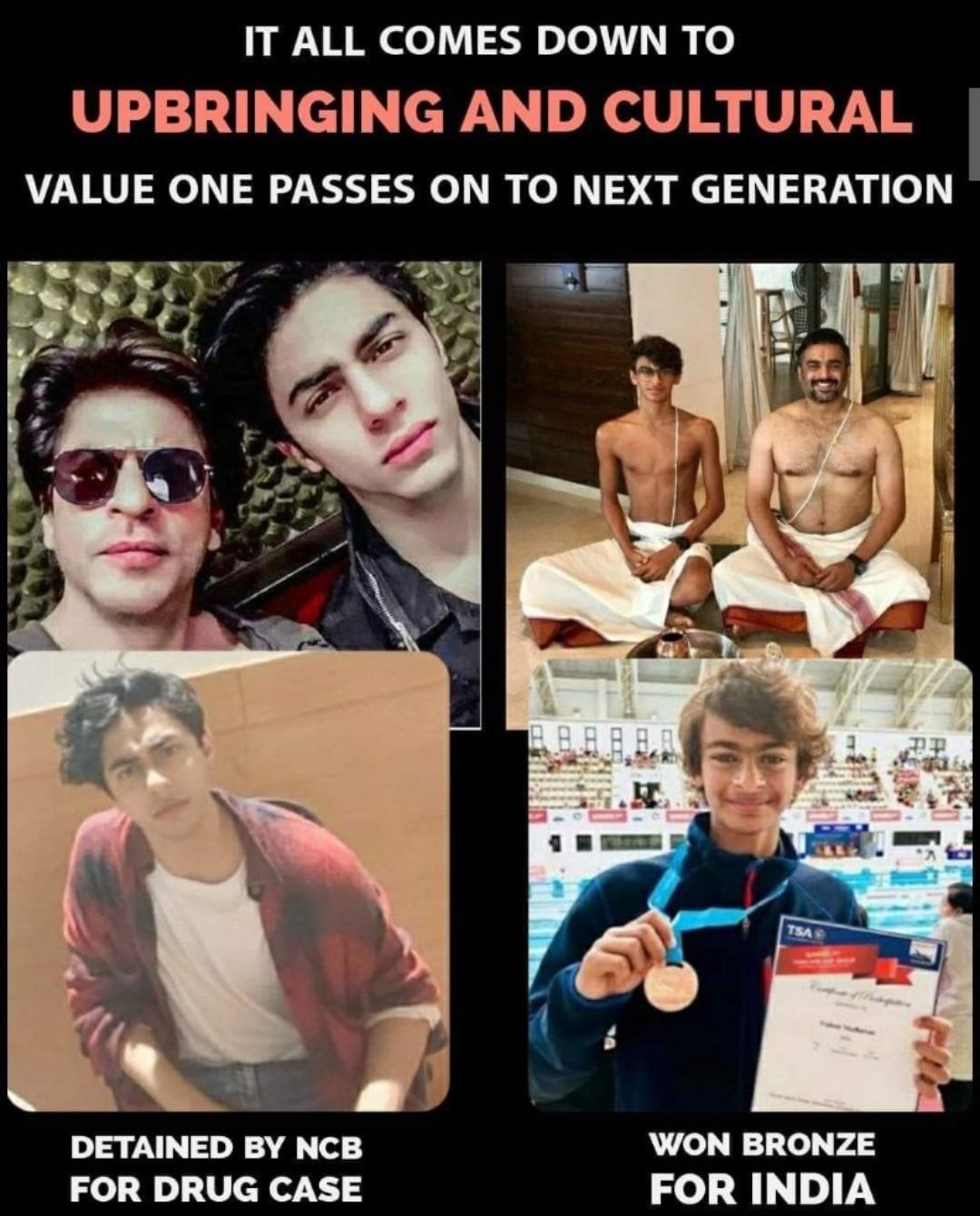

The offspring of celebrities are subject to intense scrutiny in India, and those of Bollywood celebrities most of all. No drugs were recovered from Aryan, but the court refused him bail for more than three weeks. Indian media had a field day with this story, producing countless op-eds for and against Aryan’s detention, articles on what he ate while in jail (humble pie, of course), and dissections of Shah Rukh’s flippant comments on laissez faire parenting from two decades ago. Indians couldn’t contain their collective glee, masked under tut-tutting about the drug menace and rotten rich kids. Drugs — is that what he spent his parents’ money on? Make an example of him! Let him rot in jail! Cancel his father! Boycott Bollywood!

A graphic criticizing Aryan Khan and his father

While this circus dominated Indian social media, another one started in China, also involving a pouty-lipped golden boy with implausibly perfect hair. On 21 October 2021, the Beijing police posted a picture of a piano on its Weibo account, with a coy caption — “This world has more colors than black and white, but one has to differentiate black and white. This is absolutely not to be confused.” It went viral immediately, and the wild rumors were soon confirmed. The police, aided by tip-offs from neighborhood spies known as the Chaoyang Masses, had arrested “Piano Prince” Li Yundi for hiring a prostitute. The People’s Daily, a mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched the hashtag #LiYundiDetainedForProstitution, which was apparently viewed about 790 million times and accumulated hundreds of thousands of shocked and sarcastic comments.

Li Yundi (Picture Credit: Sailing82)

Things would only get worse for the renowned pianist. Chinese music and arts associations wrinkled their noses and cut ties with him for his “extremely negative social impact” and the reality TV show Call Me By Fire literally edited him out of footage (not unlike the way Party members who fell from grace in the Soviet Union were edited out of photos).

Why are these two celebrities being treated so harshly over relatively minor offenses? Authoritarian regimes have long used the heavy hand of censorship to hide their failings, but they’ve also developed newer, subtler techniques. As political scientist Margaret E. Roberts, author of Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall, described, one such tactic is flooding, or “censoring through distraction” by overwhelming social media with information that crowds out or draws attention away from things that make the government look bad. Authoritarian governments like China and its imitators deploy this tactic regularly.

Authoritarian regimes sometimes “censor through distraction” – overwhelming social media with information that crowds out or draws attention away from things that make it look bad.

In the Li Yundi case, the New York-based media outlet NTD pointed out that the “orchestrated campaign” against the pianist appeared suspiciously close on the heels of a series of unpleasant events, including the Evergrande liquidity crisis, the Shenyang gas explosion, and the outpouring of public sympathy towards Ou Jinzhong, a fugitive who died in police custody under suspicious circumstances. Similarly, in 2014, mere hours after an earthquake killed 400 in Yunnan, Chinese media was flooded with stories about the “confession” of disgraced internet celebrity Guo Meimei, a good three years after she came into the limelight for her unseemly spending and sexual relationships.

Offices of the embattled property developer Evergrande in Chongqing (Picture Credit: MNXANL)

The Indian government is in on the game too. In the midst of an economic slowdown last year, India was riveted by the suicide of the actor Sushant Singh Rajput. The promoted narrative was that the self-made young man from the backward state of Bihar was driven to take his own life by his succubus-like actress girlfriend, Rhea Chakraborty and the cruelly elitist Bollywood in-crowd. Pro-government media channels covered little else for weeks and the offending girlfriend was sent to jail on flimsy drug charges, leading to much jubilation. #JusticeForSSR still trends on Twitter every now and then, especially when the news doesn’t quite go the government’s way. The arrest of Aryan Khan, the son of the Muslim “king of Bollywood” no less, served a similar purpose. As the journalist Barkha Dutt pointed out, the case was the “perfect deflection” from other issues, including the arrest of a minister’s son for allegedly running over and killing eight people who were protesting against new farm laws.

Rhea Chakraborty (Picture Credit: Bollywood Hungama)

But why are celebrities in particular such attractive targets for authoritarian governments?

To begin with, we are obsessed with celebrities, our fascination fuelled by the internet and gossip rags, which dangle their images and lifestyles in front of our faces, out of our reach. We get to “follow” them on social media, our noses pressed to the glass as they sell us the dream, the escape, the experience. Except that nothing really changes for us no matter what we buy. They are the haves, with money, fame, and influence that often seems disproportionate to their talent (if they have any at all), while the rest of us remain part of the toiling, faceless masses. Celebrities are objects of desire, but they also represent gross inequalities. Understandably, our fascination with them has a strong undertow of envy and resentment. We crave what researchers Steve Cross and Jo Littler call “leveling through humiliation.” Let’s face it, nothing gets as much traction as a celebrity brought low.

This brings us to schadenfreude — a German loanword describing the joy (freude) we feel at the harm (schaden) others suffer. This unworthy emotion is universal and part of the human condition, but many believe the internet has taken it to a new level, allowing us to join a jeering online mob to tear down a celebrity from the comfort of our own home.

Some governments know how to exploit this. Not only does a celebrity takedown help distract the public from the government’s failings, it also satisfies them by appealing to this sense of schadenfreude and reminds them who’s boss. At a stroke, the celebrity, the object of envy, becomes just like everybody else, maybe even worse off, restoring a sense of fairness and balance, whilst the punitive state appears righteous, egalitarian (everyone must follow the same rules!), and all-powerful – that is, so long as the takedown seems well-deserved. It’s a cheap and effective way to distract, entertain, and overawe the restless masses while also bringing in line the entertainment industry — which both India and China have recently targeted as a corrupting influence.

Not only does a celebrity takedown help distract the public from the government’s failings, it also satisfies them by appealing to this sense of schadenfreude and reminds them who’s boss.

In addition, these takedowns can deepen inter-group divisions, but strengthen intra-group affiliation. This is particularly useful for the Indian government, which has always used the politics of polarization to its advantage. Unsurprisingly, supporters of the populist Hindu right wing government are gleefully celebrating the comeuppance of “Bollywood druggies,” while the liberals are wringing their hands about the two-in-one persecution of the film industry and Muslims.

However, people in general are neither as gullible nor quite as bloodthirsty as some governments might hope. We want celebrities to pay for their crimes, but we love them too. We want to give them a chance at rehabilitation and redemption. Schadenfreude can dissipate and be replaced with empathy for the wayward celebrity, especially when the punishment goes so far that it no longer look like justice.

In China, many people are now questioning whether Li Yundi needed to be cancelled as thoroughly as he was. Even a few prominent musicians expressed their discomfiture, including one who told the South China Morning Post that “people should show more sympathy instead of gloating over his misconduct.” Another said he should be given “an opportunity to correct himself,” since other musicians abroad also “reformed themselves” after doing “stupid” things in their youth. In India, there has been a similar outpouring of sympathy for Aryan Khan and several journalists have criticized the harsh treatment meted out to him.

The other problem with excessively punishing celebrities for minor infractions is that the government’s zeal can backfire in unexpected ways, highlighting its own shortcomings and wrongdoing.

When tennis star Peng Shuai accused former Chinese Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault, far from providing accountability, the Chinese government responded by censoring her story, blocking searches and deleting posts that even hinted at the scandal. Yesterday, the Daily Mail reported that she has since vanished, likely into the Chinese security state. This would be bad enough in itself, but the Chinese government’s efforts to protect Zhang appear all the more egregious when contrasted to the heavy-handed way it treated Li Yundi. The state broadcaster CCTV, which had so much to say about “social conscience, morality, and dignity of the law” when Li was involved, was now deafeningly silent. This exposed the Chinese government’s hypocrisy and dented its credibility as a moral authority.

Zhang Gaoli (Picture Credit: Fortune Live Media)

The Aryan Khan case has caused more serious problems for India’s government. The opposition-run government of Maharashtra state — where the film capital is located — has taken up cudgels against the federal government and accused lead investigator Sameer Wankhede of corruption and other misconduct in the cruise ship raid. The federal government is now facing uncomfortable questions about its role in orchestrating a “fake drug bust” and about some of its own leaders having criminal ties. Some commentators have gleefully noted that the whole episode has “taken the lid off the holier-than-thou attitude adopted by the BJP.” On Indian social media, there is now more sympathy for Aryan Khan…and a fair amount of schadenfreude at the squirming of the BJP government. Ask a Hindu, and they might call it karma.