Your Odds of Dying From COVID-19 Depend on How Polluted Your Air Is

By James Workman

Staff Writer

6/4/2020

The silver lining from the pandemic lockdowns has been that people can breathe deep under clear skies. From Asia to Europe to the Americas, idle traffic and industry have slashed air pollution faster than many can recall. NASA showed nitrogen dioxide “plummeting” over China while analyses found greenhouse gas reductions “absolutely unprecedented.”

What few urbanites could appreciate until today is that cleaner air also makes the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) significantly less deadly.

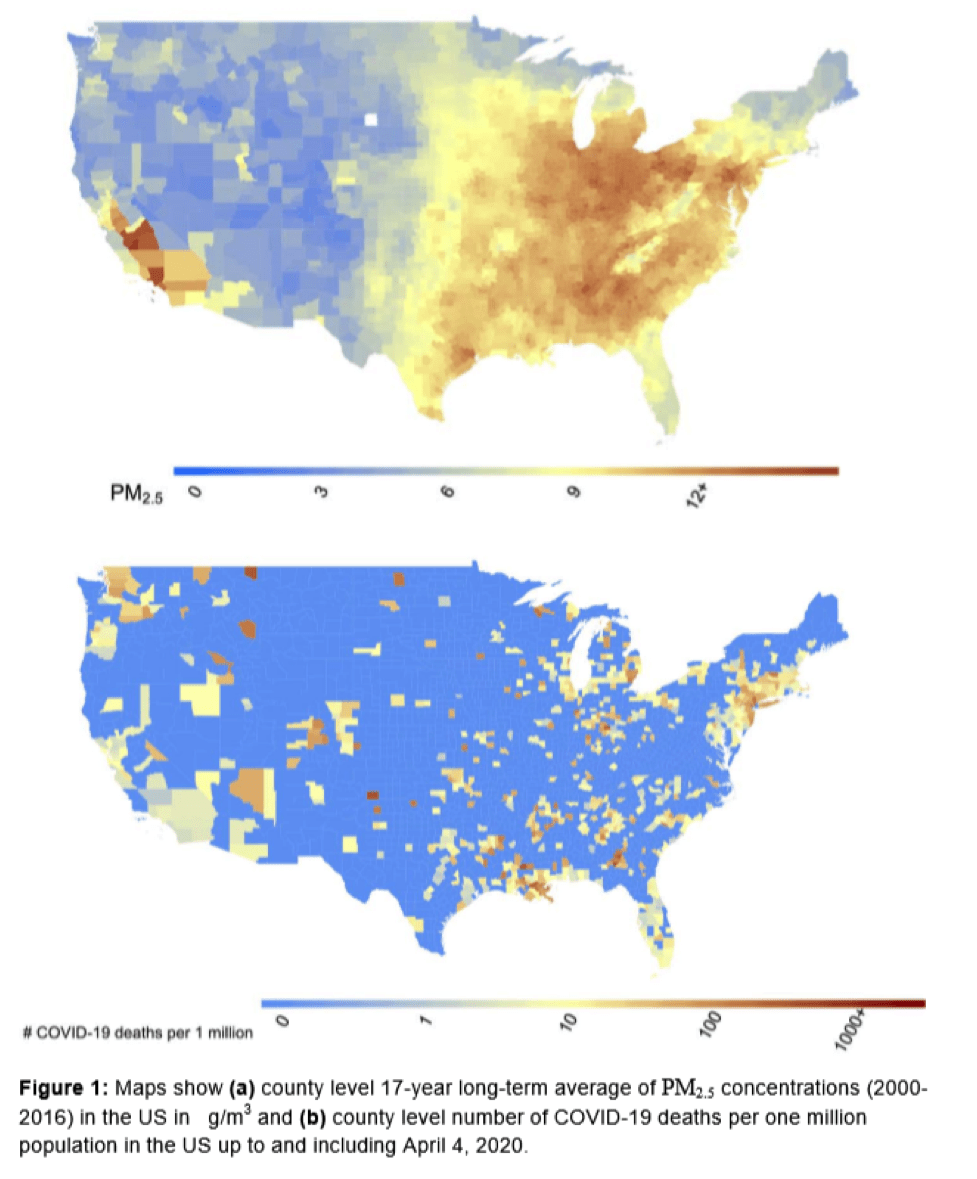

In a new study, a team of Harvard University statisticians and researchers from the T.H. Chan School of Public Health collected reams of data from 3,080 counties across the United States and combined COVID-19 death rates with 17 years of pollution data. The sample captures 98% of the US population, and controls for poverty, smoking, and population density. It found people breathing higher levels of pollution – measured as microscopic particulate matter (PM2.5) – were 15% more likely to die from the infection than those in regions with cleaner air.

The study reinforces findings from previous outbreaks. Its findings have significant implications for how – and, given finite resources, where – public health officials respond to the immediate crisis. They may focus more energy in hospitals that service poor and minority populations, often located in more polluted areas.

Looking ahead, this impacts public policy, legal liability, and the extent to which national, city, and county officials chose to regulate and enforce sanctions on emissions. “A small increase in long-term exposure to PM2.5,” the authors concluded, “leads to a large increase in COVID-19 death rate, with the magnitude of increase 20 times that observed for PM2.5 and all-cause mortality.” Those results “underscore the importance of continuing to enforce existing air pollution regulations to protect human health both during and after the COVID-19 crisis.” For example, had Manhattan reduced concentrations of particulates by one microgram per cubic meter over the last two decades, that borough could have prevented 248 people from dying of coronavirus.

Had Manhattan reduced concentrations of particulates by one microgram per cubic meter over the last two decades, it could have prevented 248 people from dying of coronavirus.

Every outbreak involves a “case fatality rate” (CFR) that tracks, among those infected, who and how many die. So, while often compared to seasonal flu, COVID-19 appears seven to seventeen times more lethal. Early in any evolving outbreak, the initially baffling range – from Germany’s low rate to Italy’s high – may vary by case demographics, testing, or viral load. To these variables, officials from Mumbai to Mexico City can add the previously obscure but now obvious and increasingly consequential risk factor of what people in an infected city are forced to inhale.

Dirty air and viral germs may seem unrelated. After all, soot isn’t contagious. Handshakes don’t spread sulfur dioxide. Yet, like overlapping circles in a Venn diagram, the two vectors fatally intersect, attacking the same at-risk host population from different pathways. Airborne particulates gradually infiltrate the human host from the outside to cut short 7 million lives. COVID-19 quickly hijacks our cells and spreads from within, further driving up demand for ventilators and body bags. Separately, our respiratory immunity may withstand constant aerial attack by pollution, or resist sudden viral invasion. But the combined assault from both at once can be deadly, especially for the elderly and those already suffering chronic respiratory ailments like asthma.

Separately, our respiratory immunity may withstand constant aerial attack by pollution, or resist sudden viral invasion. But the combined assault from both at once can be deadly.

Over time, scientists have established the link between particulate matter and “increased pathogen virulence” for pneumonia and influenza. Many also now see air pollution as a COVID-19 “threat multiplier.” Aaron Bernstein, director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, also at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, warned that those inhaling particulates, whether by choice from smoking cigarettes or involuntarily from breathing dirty air, are going to fare worse if they contract COVID-19.

How much worse? The answer depends on location and recent history, especially for polluted regions in Asia and the Middle East. In addition to the new study, our past offers prologue for what’s to come. A century after the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic, Carnegie Mellon Professor of Economics and Public Policy Karen Clay and her team studied how much fossil fuels impacted the flu’s fatality rate. Factoring in population density and temperature, they found, on average, that of 10,000 people in cities burning the least coal, the flu killed 46; in cities with higher coal burning, the flu’s toll was 57. That 20% difference is similar to the results of the Harvard study, which found people breathing higher levels of pollution 15% more likely to die from COVID-19.

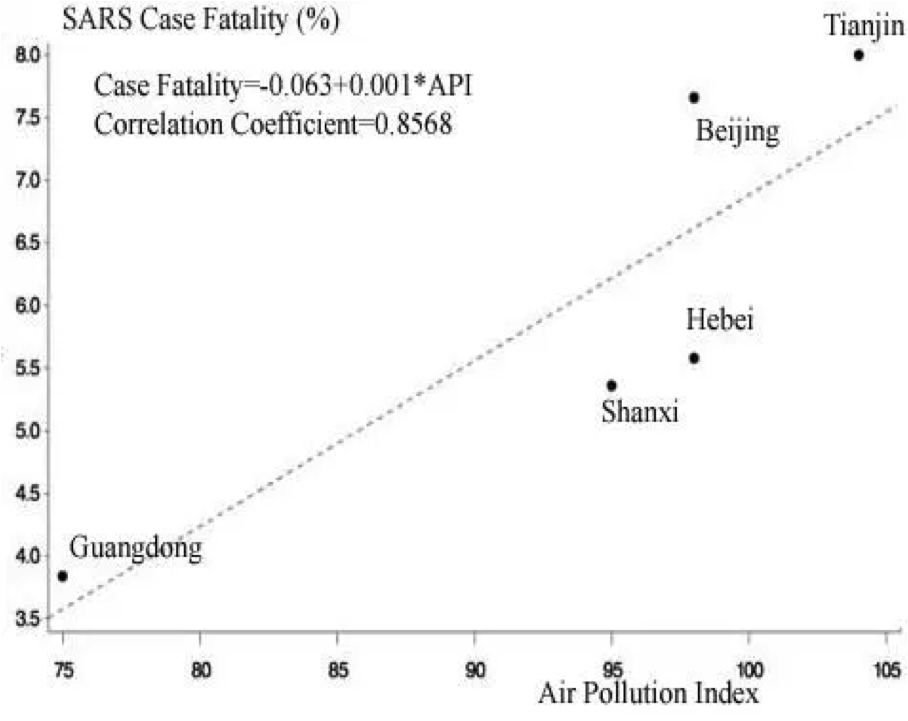

In a related study, Dr Zuo-Feng Zhang, the associate dean for research at the University of California, Los Angeles’ Fielding School of Public Health focused on another zoonotic (animal-originating) coronavirus strain, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Global health officials found that SARS initially killed in 349 out of 5,327 cases, yet fatality rates varied by geography. Officials looked at treatment facilities, sex ratio, age distribution, socioeconomic levels, and population density. No signal emerged from the noise, until Zhang’s ecological study cross-evaluated mortality data against an air pollution index to yield a clear linear trajectory: as the index rose 74 to 104, SARS fatality rate doubled; infected patients were 84% more likely to die. Zhang, contacted by the New York Times, found the COVID-19 study “very much consistent” with his own findings.

Controlling for other variables, H1N1 researchers looking at fatalities across countries also found air pollution to be an important risk factor. And in the small sample of the world’s previous coronavirus outbreak, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital highlighted how Saudi Arabia’s death rate of 44% was twice South Korea’s (22%). Risk factors included age, and weakened immunity from inhaling particulates. South Korean air isn’t pretty, until compared with Saudi Arabian cities – the Dammam, Al Jubail, Jeddah, and Riyadh hot zones both for MERS and toxic pollution – where people breathe air seven times dirtier.

Riyadh (Picture Credit: Jon Rawlinson)

To the extent that the miasma of emissions increases mortality, the converse also holds. Katherine D. Walker, senior scientist at Boston’s Health Effects Institute, says lowering air pollution can buffer the virus’ worst effects. Indeed, one provocative analysis by Marshall Burke of Stanford predicts that the two months of reduced emissions in China “likely has saved the lives of 4,000 kids under 5 and 73,000 adults over 70.” Even his most conservative estimate found clean air saved twenty times more lives than the virus claimed.

Alas, our clear skies probably won’t last. As economic activity ramps back up, emissions may follow. Yet we need not choose between economic strength and human vigor. Leaders can and do leverage stimulus funds to lower pollution per GDP. China has been gradually clearing its air, even while the Trump administration moves in the opposite direction. In the last two weeks, under the guise of “crisis response,” Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency first froze environmental laws to let industry pollute at will, then weakened fuel economy standards, despite EPA findings that, by lowering absenteeism and boosting overall worker productivity, the Clean Air Act benefits exceed costs by a factor of 30 to one.

China has been gradually clearing its air, even while the Trump administration moves in the opposite direction.

By growing the economy while saving lives, clean air pays for itself. Unlike masks, ventilators, or special medical care, benefits from this democratic “treatment” are evenly distributed among rich and poor alike. And while drug treatments may have side effects, no one has been known to sicken or die early from air that’s gotten just a little too clean.

Social distancing is effective, and worth the pain. The economies of cities and nations that bite the bullet and take early and forceful lockdown measures to suppress the virus will likely recover faster and stronger than those who don’t.

At the same time, those local, national, and global health officials striving heroically to drive down COVID-19’s death rate need to do more than focus on “flattening the curve” of contagion on the ground. Armed with this knowledge, they can also more aggressively reduce our exposure to pollution in the air.

Related posts:

The Culture Factor in COVID-19

Modi and His Supporters Face a COVID Reckoning

Tablighi Superspreaders in Pakistan

The Moral Foundations of Anti-Lockdown Anger

Are Anti-Lockdown Protests Legal?

Allegory in the Time of Coronavirus

Japanese Culture Isn’t Designed to Handle a Pandemic

The Coronavirus and the Crisis of Responsibility

To See How Coronavirus Outbreak might Play Out, Look at This Virtual Plague

FAKE NEWS | Nothing to Worry About, Says Wuhan Official From Inside Biohazard Suit