Allegory in the Time of Coronavirus

By Lisa Yin Zhang

Staff Writer

14/4/2020

Picture Credit: Jules & Jenny

My country, it seems, is newly hungry for allegory. When Donald Trump was elected, the reeling American people sent sales of Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here, a novel about the upset election of a Trump-ian politician, skyrocketing 90 years after publication. When an accused sexual assaulter rose to the ranks of the Supreme Court, The Handmaid’s Tale, a show about an authoritarian, misogynist society, became a cultural touchstone. And when the Coronavirus pandemic swept the states, the nine-year-old film Contagion began trending on Amazon Prime.

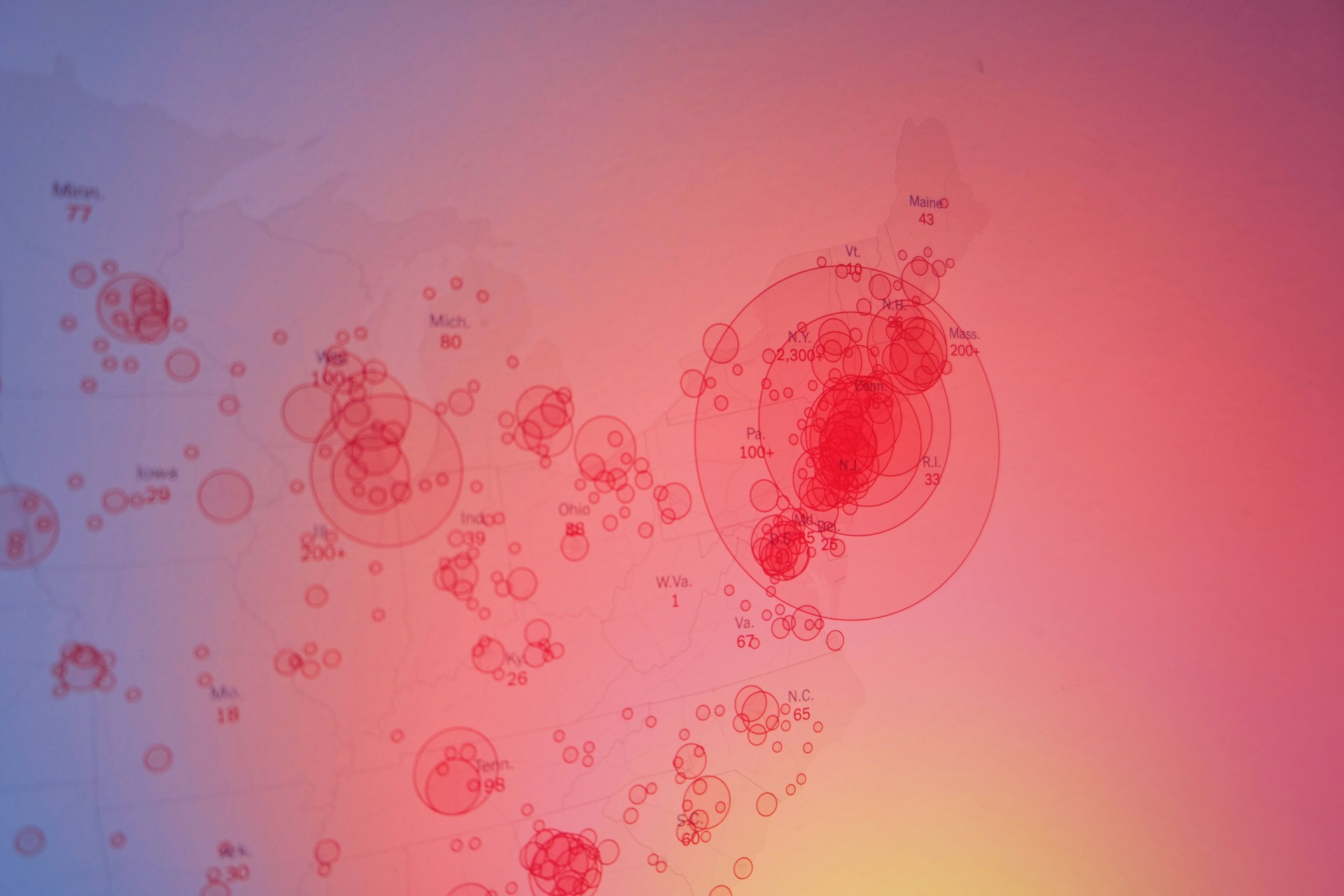

What we should have been watching instead: COVID-19 beginning to ensnare Wuhan, then China more broadly, then South Korea, Iran, Italy, Spain. Hospitals overwhelmed; the death toll rising; bodies piled in streets. The horror of lockdown.

Instead, I write this as China reports zero new cases, and the deaths from New York alone have surpassed that entire country’s total. Well, folks — looks like it happened here.

***

This is, to some, an allegory about China.

“All third world texts,” wrote the American critical theorist Fredric Jameson, “are necessarily, I want to argue, allegorical, and in a very specific way: they are to be read as what I will call national allegories.”

It goes like this:

It began in a wet market in Wuhan, where pangolin carcasses pile atop bats piled atop dogs, cats, you name it. It spread because of the dirty Chinese practice of eating those poor animals, a practice, yes, more barbaric than eating veal, eating paté. A diseased bat, a sick Chinese — not so big a leap, no? They were guilty of barbarism, authoritarianism, censorship, a whole list of democratic injustices. So came this plague of moral punishment.

We watched it happen with mild interest, just another story awash in a sea of stimuli. Even when the death toll rose calamitously, when the Chinese government instituted the largest quarantine in history, well, those were only more incomprehensibly large numbers to come out of an unthinkably huge country. (Recall Stalin’s quote: “a single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.”) And, later, when China seemed to have quashed the virus, while we were drowning in it, it was only because of the cruel efficacy of its authoritarian government, and the fearful, subservient nature of its people.

“[A] third-world novel,” Jameson continued, “tends to come before us, not immediately, but as though already-read.” We know the tale; we fit it in.

Day 18 of lockdown in New York: My president continues to refer to the disease as the “Chinese virus.”

***

But wait, let’s backtrack a bit.

It’s the last day of 2019; I’m at my boyfriend’s house to celebrate the New Year. I’m coughing conspicuously.

“You better watch out for that,” chides his uncle, holding a flute of champagne, and, I like to imagine, wearing a festive hat festooned with a glittery “2020.”

“It’s only a cough,” I protest. I don’t remember what I’m wearing, what I’m holding. “I don’t feel sick or anything.”

He puts a cracker with cheese on it in his mouth. “That’s how it always starts,” he says ominously, mouth full of cracker.

And somewhere far away, unbeknownst, the Chinese government reports the first case of a novel coronavirus.

***

For Jameson, the crucial difference between a third-world text and a first-world one is the violation of an unspoken public/private split.

“One of the determinants of capitalist culture,” he wrote, “is a radical split between the private and the public, between the poetic and the political, between what we have come to think of as the domain of the unconscious and that of the public world of classes, of the economic, and of secular political power.” He concluded: “It is precisely this very different ratio of the political to the personal which makes such [third-world] texts alien to us.”

Note: Jameson issued some academic disclaimer about the use of the terms “third world” and “first world.” Doesn’t matter. What he meant: there are “shithole” countries, and non-“shithole” countries.

Hence, he tackled China, actually a second-world country (really those labels are stupid), through the lens of the writer Lu Xun. The story is about a man who suffers a nervous breakdown, who begins to believe that the people around him are secretly cannibals.

Jameson believed the story is actually an allegory about a “maimed and retarded, disintegrating China.”

“The libidinal center of Lu Xun’s text,” says Jameson, “is the oral stage, the whole question of eating, of ingestion, devoration, incorporation, from which such fundamental categories as the pure and the impure spring.”

He could just as well be speaking about now. The oral fixation as allegory — how fitting for a wet market disease.

***

Here, under lockdown, I scour my journal entries for mentions of the virus.

The first, amazingly, is on March 5th, a full four days after the first case is reported in New York, two months after the first case in the US, three months after the WHO declares a global health emergency.

It takes place at 7:30 pm: a homeless man, stalking up and down the 1 train, proselytizing on a whole litany of subjects, one blending seamlessly into the next. All normal; but it takes a surreal turn when he starts talking about hand sanitizer. Hand sanitizer? On the subway? From a homeless person?

“Stay safe,” he said to all of us, then jingled his cup of coins, as if in emphasis.

***

White light suffuses the city, bathes the streets. It’s warm for March. There’s birdsong in New York. The cherry trees are budding.

March 6th: Mayor De Blasio urges sick New Yorkers to stay home.

In my house, we are greeted some mornings by the cooing of pigeons, who strut impetuously over our kitchen counters, send cloves of garlic rolling. Sometimes they hold garlands of twigs in their beaks, some still with crinkled little leaves attached. Irritating, but harmless.

But something’s in the air. On the train I look around and think, we’re too close together. I consider taking out my hand sanitizer, gifted to me by my mother, who worries too much, but don’t.

On the train I look around and think, we’re too close together.

I cough into the crook of my elbow. The lady beside me looks at me with disapproving alarm, but doesn’t actually get up and move.

When I’m at the gym, I think, maybe we shouldn’t be here. And then: But everybody else is here — can they all be wrong?

March 7th: Governor Cuomo declares a state of emergency. I read this on my phone at work, where posters have begun to pop up on how to wash your hands.

On March 13th, work shutters: we’re going remote.

March 14th: the first death in New York.

March 15th: schools close. 16th: bars, restaurants, gyms follow.

Whatever you want to call it, it’s a lockdown. The public and private, it seems, are colliding — even in this country.

***

Some might say, then, that this virus is really an allegory about capitalism, about globalization.

“It’s such bullshit,” says one of housemates, pacing around the living room-cum-workplace, beer in hand. “So meaningless. It’s like the epitome of useless, meaningless work.”

He says this about his corporate job, for which he is handsomely compensated, a job which could not be done from home until it had to either be done from home or not done. Documents, spreadsheets, forms: each time he turns something in his bosses are impressed with the speed with which he completes the assignment and also, it seems, vaguely stumped about what next to send.

Some days he doesn’t get an assignment until noon.

Before, at least, he was physically at work. There were other things to do to keep busy: files to file. Shit to shoot. Time spent not working then was still spent not working at work. Now what?

***

We watch the Democratic debate, a “town hall,” except there are no townspeople — that day, the CDC advised a ban on gatherings of more than 50 people.

The two men stand six feet apart, the depth of a grave. Often they face each other behind their podiums and bicker, and watching feels like intruding upon a private conversation between two old men.

The two men stand six feet apart, the depth of a grave.

The broadcast is served by a skeleton crew; there are strange cuts in programming. The camera hovers a beat too long on the moderators, who nervously shuffle papers. The slight sound echoes eerily in the empty studio.

Besides, we’re a little late to it; we can’t find a broadcast that begins in the beginning, except one off a sketchy website. The word “live” flashes sinisterly over Bernie’s face; the subtitles, often mangled, spill across Biden’s forehead. “FOLLOW, LIKE, SHARE,” rolls a neon banner ceaselessly across the bottom of the screen.

For moments at a time, I forget that one of these men might be president, that that’s why we’re watching. It doesn’t exactly feel like there is democracy, even a republic, in a time like this.

The lockdown, then, lays bare the incredible absurdity of all our systems, our institutions. It is, in part, the criss-crossing of flightpaths, of goods, of people, which global capitalism permits — no, demands — that has wrought this wretched disease.

It is, in part, the criss-crossing of flightpaths, of goods, of people, which global capitalism permits — no, demands — that has wrought this wretched disease.

The stock market plunges. 16 million people file for unemployment.

There’s a sense that the government’s failing, a growing mistrust of foreigners.

Globalization, which dangled utopian promises of all the world coming together, has instead ripped the world savagely apart, quartering even those of the same flock to different homes. It is a disease that punishes closeness.

***

Jameson is, perversely, kind of right in one aspect.

After the savage collision of the public and private due to the global pandemic, mandated lockdown, etc, etc, the middle class retreats into their middle-class domiciles. The public and the private are again sealed off, this time pneumatically.

Meanwhile, the world inside gets smaller.

***

My phone dies one night while I am cutting my boyfriend’s hair; it needs to be reset. When I do, all my apps are gone, my contacts deleted.

I’m cognizant of the sudden silence but not exactly sure what’s missing.

It takes me more than a day to re-download the New York Times; a lot has happened to the world in the interim, but nothing at all has happened to me.

A couple days later I realize I’m missing WeChat, where my Chinese relatives chat, a little pitying, about the state of the virus in America. Then, Slack, where neurotic prospective Fulbrighters fret about the state of the world, or at least the sites of their individual scholarships. Some apps I don’t ever bother to re-download.

It’s easy enough not to keep up when there’s no one around to say, “How did you not know that?”

***

Maybe I’m quartering onions for a stew when I suddenly think, “What, even, is the stock market anyway?” I have no idea. I’ve never really had an idea. It drops when people lose faith in it, this I know, abstractly. Like Tinkerbell.

***

Vocabulary catches and holds in our newly shrunken world. When a housemate coins “Coronaworld,” we laugh. “It sounds like a theme park,” says another. But now we say it all the time: “Do you think that’s open? It’s Coronaworld,” or, more commonly, “When Coronaworld is over…” Then there’s “Fooniverse,” portmanteau of “Food Universe,” the closest grocery store.

These newly-wrought catchwords catch, stick, tunnel in — like a virus with signature little spikes.

Is that good? Is that a good metaphor? I’m starting not to know.

This shrunken world, because of the sudden paucity of things, because of the sudden excess of time, becomes newly rife with allegory, metaphor, meaning. Normal human functions begin to acquire the significance of ritual — the sound of the ladle hitting the metal pot sounds like a gong, the beginning of something solemn. The fact that my boyfriend dreams of the same bus stop night after night must mean something.

Normal human functions begin to acquire the significance of ritual.

One day, I notice the product of the pigeons’ plotting: a gnarled loop of twigs. A nest. I brush it out of the window. “Ooh,” I think. “That’s good.”

***

One last time, then. This is an allegory about allegory. About things accruing meaning, about making one’s own meaning.

In Coronaworld, I allege, all things are, necessarily, allegorical. They stand in for something outside. They have to. This can’t be it.

***

I think: “You know what would be a good article title? Love in the Time of Coronavirus.” You know? Because of Love in the Time of Cholera?

I haven’t read it. So I read the Wikipedia article; I’m getting excited about all the possibilities. Ostensibly a book about true love, a love that persists across decades, it’s really positing a more complex definition of love: that it can be learned, that it can be multiple, simultaneous, that it is not easily categorizable. Could this article be about defying too-easy categorizations of people — Chinese people, Asian Americans? Márquez himself said about the book, “You have to be careful not to fall into my trap.” I rack my brain. What’s the trap here? The word “cólera,” Wikipedia tells me, can also denote rage. There’s something there, I think, an American indignation at its subjugation. I could go on. The premise, I admit, spins solely out of the conceit.

I Google the title. I’m chastened. This is not an original idea.

Maybe, then, it’s best not to write about the coronavirus at all. “Art,” chided Sloane Crosley in the New York Times, “should be given a metaphorical berth as wide as the literal one we’re giving one another.” It’s the logical end to the problem she identified. It’s the article to end all coronavirus articles.

But notice — even her appeal to stop making art about the virus, at least for now, is done artfully. The metaphorical berth is likened to the physical berth, distance physical and allegorical. It’s like she can’t help herself. She wrote a coronavirus article about not writing coronavirus articles.

We’re all out here trying to corner every possible angle of this thing and extrapolate from it. All of this allegorizing is a way to hide. A way not to have to sort through the horror of a new world that ends at the front door – no workplace, no school, no friends except through screens – and the dearth of meaning that comes with it. To allegorize in this newly depopulated universe is to say: my pushing these sticks out of this window must mean something. My making tea every day must mean something. My continuing to get out of bed, day after day, must mean something.

And it is a luxury: there are people who, while you ponder your ladle, must go outside to stock your grocery stores, to transport your goods.

But it’s also a way to survive. A way to empathize, a way to connect. Is it a coincidence that Albert Camus, the writer of The Plague, also concluded, of Sisyphus, the Greek sinner doomed to repeatedly push a boulder up a hill – a meaningless, absurd act – “We must imagine Sisyphus happy”?

Maybe.

Probably.

I’m going to put them together, because that’s what writers do. We make connections. We make things stand in for other things. We make meaning.

So here I am, in my home, at my desk, writing these words. And there you are, in your home, reading what I’ve written. In the time of coronavirus, that means something.

Related posts:

Ed Simon on Wonder in the Time of Coronavirus

Modi and His Supporters Face a COVID Reckoning

Tablighi Superspreaders in Pakistan

The Culture Factor in COVID-19

The Moral Foundations of Anti-Lockdown Anger

Are Anti-Lockdown Protests Legal?

Your Odds of Dying From COVID-19 Depend on How Polluted Your Air Is

Japanese Culture Isn’t Designed to Handle a Pandemic

The Coronavirus and the Crisis of Responsibility

To See How Coronavirus Outbreak might Play Out, Look at This Virtual Plague

FAKE NEWS | Nothing to Worry About, Says Wuhan Official From Inside Biohazard Suit