Australia Is Uniquely Bad for Defamation

By Cassidy Warner

Staff Writer

31/8/2022

Picture Credit: wiredforlego

When you think “Australia,” you think “a liberal democracy,” a country that upholds fundamental freedoms. In many respects, Australia compares well with other liberal democracies. Australia’s Freedom Score (95 out of 100) is on par with or better than countries like the UK (93/100), New Zealand (99/100), Canada (98/100), Germany (94/100), France (89/100), and the US (83/100). The country regularly ranks high on freedom indexes and democracy indexes and all sorts of human rights and civil liberties metrics.

But when it comes to freedom of expression and freedom of the press, Australia is uniquely terrible. All the others have enshrined free speech in either their Constitution, a bill of rights, or other legislation (like the UK’s 1998 Human Rights Act). Australia, on the other hand, lacks an express right to free speech, relying solely on common law precedent and UN conventions that, when combined, maybe, sort of, subject to interpretation and limitation, infer a right to freedom of expression – or more precisely, “an implied freedom of political communication,” which is already a qualified version of free speech. Yet, in true “she’ll be right” fashion, the approach of Australia’s High Court has been to assume that the Constitution would likely have meant to protect an individual’s rights and freedoms, and therefore to infer a blanket implied freedom of expression until presented with an explicit challenge.

The problem with this approach is that there has been far more legislation explicitly limiting free speech than there has been protecting it.

Australian defamation law is the bane of journalism because it legally enshrines the right to reputation in a manner that overrides the implied right to free speech. The 2005-2006 Uniform Defamation Acts specify that they aim not to place unreasonable limits on the expression of free speech (s3(b)), but then promptly forget about that in further provisions. The only other mention of freedom of expression is as the last item on a list of “potentially” applicable considerations that do not need to be taken into account when determining whether the defamatory material was of public interest (s29A(3i)). In other words, Australian defamation law makes the right to freedom of expression a footnote when it should be equally as important as the right to reputation.

Australian defamation law is the bane of journalism because it legally enshrines the right to reputation in a manner that overrides the implied right to free speech.

Journalists are keenly aware of this imbalance. In its 2021 Press Freedom Survey, the Media, Entertainment, and Art Alliance (MEAA) found more than 88% of Australian journalists thought that the defamation laws made reporting more difficult; nearly a third reported having a news story killed in the last 12 months over fears of defamation action; and almost 8% had actually received a defamation writ within the past two years. Louisa Lim, a former correspondent for the BBC and NPR in China, now a Senior Lecturer in Journalism at the University of Melbourne, has even compared the muzzling effect of Australia’s “oppressive and notoriously complex defamation laws” to the regime of censorship in authoritarian China: public interest journalism is stifled in both countries, just in very different ways.

Defamation law is, of course, not unique to Australia, so what is it about Australia’s legal framework that is so unusually harsh?

Defamation is the publication of material, whether written, spoken, or pictorial, that harms a person’s reputation. A plaintiff, the aggrieved person, brings a defamation action against the person or organization that published the defamatory material, the defendant. An example of a defamatory statement might be: “The plaintiff walked out of an electronics store with a laptop he did not pay for.” Defamation is not limited to the exact wording of the statement; it also includes anything it implies. For example, the plaintiff could claim the statement implies that he’s a thief, but he can also claim it implies any number of other things, for example, that he is a liar, a member of the mafia, or a spy. Depending on the situation, some of these claims might sound bizarre and ridiculous, but it will be up to the jury (or judge, in federal court) to determine which implications are valid. But because defendants don’t know which implications will be accepted by the court, they usually respond to all of them, just in case.

In most Western jurisdictions, like the US, Canada, and New Zealand, it is up to the plaintiff to prove that they have been defamed by the defendant – making the defendant innocent until proven guilty. But in Australia, it’s the opposite: the burden is on the defendant to prove that they have NOT defamed the plaintiff, which means they are guilty until proven innocent.

This makes it much harder for people to defend themselves against defamation lawsuits. Bernard Keane, the political editor of Crikey magazine, one of few remaining independent Australian news sources, spoke of his own experience being sued for defamation: “It is distressing. It is distressing personally. It is distressing for your publication. Afterwards it leaves you with a sense that you are performing without a net.” Like Keane, many Australian journalists and whistleblowers have been buried under the weight of the paperwork needed to prove their innocence, and all the while their other public interest stories remain uninvestigated and unwritten because there is no time left once the legal system has extracted its pound of flesh. Chris Masters, who has won the Walkley Award for excellence in journalism five times, for instance, spent 10 years defending a defamation claim (that he ultimately won) and almost quit the profession because of the stress.

Similarly, in the process of proving that defamation has occurred, most Western jurisdictions require the plaintiff to prove how, and to what extent, the alleged defamation has harmed them (e.g. through lost business opportunities or lost revenue). But in Australia, prior to the 2021 reforms (more on that later), the plaintiff did not have to prove harm at all; the simple existence of unflattering material (which is presumed to be untrue) was considered proof enough that harm had been done to the plaintiff (Defamation Act 2005, s7.2). Thus, the plaintiff has a leg up from the get-go as they are automatically entitled to damages if the defendant cannot establish a defense.

The maximum damages that can be awarded for non-economic harm is $296,000 (all figures have been converted to USD) (an amount that has steadily increased from $171,000 in 2005); but this figure has regularly been exceeded. For example, a South Australian lawyer won $512,000 over a campaign of negative Google reviews; former NSW Deputy Premier John Barilaro won $489,000 over “vulgar” videos on YouTube that Google had refused to remove; the Wagners, a regular (albeit wealthy) family, were awarded $1.75 million after a popular radio host, Alan Jones, made a series of “vicious and spiteful” claims that the family were criminally responsible for flooding fatalities on their property; Geoffrey Rush won $2 million over claims of inappropriate behavior on set; and Rebel Wilson won $3.2 million (later reduced to $410,000 on appeal) over claims that she was a serial liar.

And, in addition to the fact that courts can simply override the cap if they feel that aggravated damages are appropriate, plaintiffs can also bring separate motions against different publishing entities even if they are all owned and operated by the same company, effectively rendering the cap pointless, as each case will entitle the plaintiff to separate damages if they win.

Another key difference between Australia and other liberal democracies is the fact that Australia doesn’t make a distinction for public figures. Although the accepted precedent is that “a man who chooses to enter the arena of politics must expect to suffer hard words at times,” (Australian Consolidated Press Ltd v Uren (1966)), the reality is that Australian politicians are some of the most prolific plaintiffs. They regularly feel the need to protect their thin skins, clogging up the courts by suing everyone from senators to the prime minister, from Australia’s publicly funded broadcasters (like the ABC) to random, small-fry Twitter commentators over the smallest slights.

Another key difference between Australia and other liberal democracies is the fact that Australia doesn’t make a distinction for public figures.

In most other Western jurisdictions, there is a higher threshold for defaming public figures (like politicians). In the US, for instance, a public figure suing for defamation must prove the defendants acted with “actual malice” (i.e. knowing that what they were publishing was untrue) rather than just negligence in publishing something defamatory. Australia does not have this requirement. As with freedom of speech, the closest Australia comes to differentiating defamation of a public figure is the implied freedom of political communication. But this just makes it slightly easier for the defendant to argue that the publication was in the public interest – the number of successful defamation suits brought by politicians show that the courts interpret the implied freedom of political communication very narrowly.

Another issue is the shortcomings of defenses available to Australian journalists and media organizations. Prior to reforms in 2021, which introduced a new defense that’s yet to be tested in court, the only applicable defenses were the defenses of truth, qualified privilege, and honest opinion (or fair comment).

When it comes to the defense of truth, it is remarkably difficult to prove something is true to the satisfaction of the court. For instance, if one of the allegedly defamatory statements or implications relates to a criminal offense (e.g. murder, corruption, embezzlement), the only acceptable proof is a criminal conviction in a court. Thus, if a newspaper alleges that the plaintiff committed an offense, it is exceedingly difficult to prove the truth of those accusations to the satisfaction of the court if criminal proceedings are not yet underway. (If they are underway, civil matters like defamation are stayed (postponed) until the criminal proceedings are concluded, but public interest journalism is often at the frontier of these investigations and defamation suits can easily outpace their criminal counterparts.)

When it comes to the defense of truth, it is remarkably difficult to prove something is true to the satisfaction of the court.

For example, Ben Roberts-Smith, a highly decorated former SAS soldier, is currently suing veteran journalist Chris Masters, as well as The Age, Sydney Morning Herald, and The Canberra Times over stories that report generic SAS involvement in “unlawful killings” in Afghanistan while on deployment. Roberts-Smith has claimed that Masters (and the newspapers) defamed him by implying that he was a war criminal, a murderer, and a domestic abuser – all serious crimes. The defendants have pled a truth defense, but government inquiries into the criminal aspects of the allegations are still ongoing, so there will be no criminal convictions for the defendants to point to. Thus, ironically, in order to prove the truth of their claims, Masters and his publishers have been forced to provide (and thus publicize) even more damaging claims against Roberts-Smith in order to also prove the truth of the implications that he drew from their original stories. The fact that the defendants have such evidence ready and are willing to take it to court should be a clear indication that the original stories were already subject to strict oversight and backed by extensive research – what the court might conclude were “reasonable” actions and conditions under which to publish the original material.

Ben Roberts-Smith (Picture Credit: Nick-D)

The defense of honest opinion, as its name implies, can only be used in cases where a journalist or commentator is offering an opinion, and so does not cover most reporting, which usually presents matters of fact.

The defense of qualified privilege essentially requires the defendant to show they had a moral, social, or legal duty to publish the defamatory material. They can do this by showing they acted “reasonably” by revealing information that is of public interest and/or for the public good. However, this defense has been interpreted so narrowly that it has never succeeded in an Australian court. So ineffective is the defense of qualified privilege, that the 2021 reforms introduced a new, similar defense of public interest to make up for its shortcomings.

The combination of these factors makes for a particularly harsh legal landscape for journalism which often takes aim at public figures and seeks to uncover evidence of misconduct and potentially criminal behavior. The result, said Karen Percy, a former ABC journalist and the current MEAA president, is an environment that severely “curtails the way [journalists] can do their jobs.” Speaking at the 2022 Sydney Writers Festival, veteran journalists like Louise Milligan, Chris Masters, and Kate McClymont all reported that their internal thought processes have changed when preparing a story: they no longer just ask themselves whether their writing is objectively true (an important ideal for all journalists to strive for), but whether or not they could prove that truth, and any adjacent implication, to the satisfaction of Australia’s peculiarly hostile courts. It was striking to see how wary all three of them were when commenting on this issue, how overly cautious they seemed when choosing their words.

To give some perspective, between 2008 and 2017, plaintiffs won 71% of the cases against media organizations that went to trial; and that number doesn’t reflect the fact that most cases are settled before trial, overwhelmingly in favor of the plaintiff. The difficulty of defending yourself, courts’ willingness to award very large damages, and the fact that the loser at trial is usually required to pay the winner’s legal fees (which can easily run into the millions), make it obvious why only about 10-15% of defamation suits go to trial. Lacking in-house legal counsel, defamation insurance, and a dedicated defamation budget, most journalists and small publications simply can’t afford to go to trial.

Between 2008 and 2017, plaintiffs won 71% of the cases against media organizations that went to trial.

Thus, rich and powerful people are able to wield defamation law like a cudgel, knowing that the law favors the plaintiff, and that the expedient option for most defendants is to settle quickly before legal costs mount.

Because defamation actions have been so detrimental to media organizations, journalists now report that legal teams comb over many of their stories, removing details that, on face value, should be easy to defend, because they don’t know how a court would see it. Louisa Lim, for instance, recounted having direct quotes removed from her articles, as well as statistics that were already in the public domain, simply because the lawyers couldn’t be too careful – self-censorship was considered better than getting sued.

They are right to be careful, because the courts have proven time and again that what the media considers reasonable assertions and evidentially supported claims, are not proof against against defamation.

For example, Dr Chau Chak Wing, a Chinese-Australian businessman has twice successfully sued media organizations, including the ABC, Nine, and the Sydney Morning Herald, over reports regarding how he’d been identified as a co-conspirator in a bribery scandal. He claimed the reports implied that he’d bribed people (amongst other things), and won an award of $191,000 in 2019, and another $403,000 in 2021. In similar circumstances in the US, for instance, it is unlikely that a defamation action would ever have been successful because Chau fits the definition of a public figure (a business leader with significant influence in spheres of public interest), and as such would have needed to prove that the ABC acted with malice. Even if, for some reason, he wasn’t deemed a public figure, it’s unlikely the courts would have accepted Chau’s argument that the reports implied he’d bribed people. If ABC was relying on the defense of truth, the burden of proof would have been on Chau to show that he hadn’t bribed anyone, which would have been determined on the balance of probabilities, rather than whether Chau had been convicted of the crime yet.

The simple truth is that when journalism faces off against Australia’s onerous defamation regime, it loses, and so does the public. Journalists have no confidence that the law will protect them when they act in good faith to report on issues of public import (like potential corruption or criminality involving public figures). Thus, it is perhaps unsurprising that only 44% of Australian news consumers agree that “the news adequately monitors and scrutinizes powerful people and businesses,” undoubtedly because it is difficult for journalists to do their jobs with a sword of Damocles hanging over their heads.

There is, however, some cause for hope.

As previously mentioned, Australia finally passed some (modest) reforms, on July 1, 2021, most notably introducing a “serious harm” threshold that plaintiffs must overcome in order to bring their case, which puts Australia more in line with other liberal democracies. The hope is that this new requirement will reduce the number of vexatious claims that operate only to silence critics through the threat of high legal fees because plaintiffs will have to outlay significant costs before the defendant even becomes involved.

The other significant reform is the new public interest defense that was designed to replace the ineffective defense of qualified privilege. This defense will protect journalists from defamation suits if they can show that publishing the defamatory material was in the public interest. However, legal experts and media executives are not optimistic. Michael Douglas, for instance, a defamation lawyer and a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Western Australia argues that the new defense will be no better than the previous defense of qualified privilege, “getting to a similar place through different wording.” Defenses like these continue to turn on debatable terms like “reasonable” and “responsible” and Australian courts have made it clear that their interpretation of these terms is not aligned with the media’s. Thus, after decades of rejecting media organizations’ defenses of qualified privilege, it is difficult to believe that the courts will suddenly be receptive to the new public interest defense. Michael Bradley, a managing partner at Marque Lawyers and a popular pundit on law reform and public policy, for instance, believes that even if the ABC had had the new public interest defense available to them, Dr Chau’s defamation case wouldn’t have turned out any differently.

These new provisions will soon be put to the test.

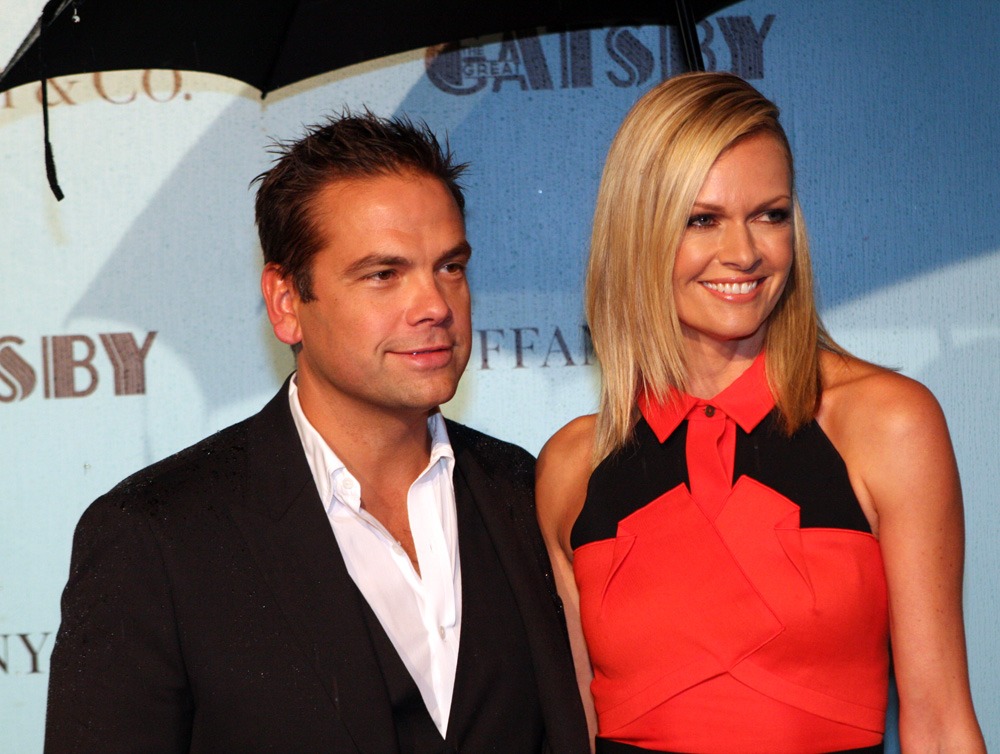

In just the past two weeks, Crikey magazine has very publicly thrown down the gauntlet, writing an open letter than was published in the New York Times that invited Lachlan Murdoch (son of media mogul, Rupert Murdoch) to sue it for defamation over an article in which Bernard Keane, the magazine’s political editor, called “Murdoch” a co-conspirator in the January 6th insurrection in the United States. (It is debatable which Murdoch this refers to: Crikey claims it refers to Rupert; Lachlan infers a reference to himself.) This case will illustrate how difficult (or not) it might be for a plaintiff to establish that they have been seriously harmed; and if Lachlan Murdoch succeeds in that respect, it will also show the efficacy of the new public interest defense.

Lachlan Murdoch with wife Sarah Murdoch in 2013 (Picture Credit: Eva Rinaldi)

(The fact that Lachlan Murdoch has chosen to sue Australia’s Crikey, which he has now done, when he hasn’t sued any American news organizations for saying similar things – presumably because the US has robust protections for free speech and freedom of the press, and a public figure distinction – shows the dismal contrast between the two countries in this respect.)

But whilst it is encouraging to see a small player like Crikey put its faith in these new provisions, many other newsrooms have been cowed into self-censorship after having the field tilted so heavily against them for so long. It will likely take some major legal victories for them to unlearn that habit.