Bridging the Culture War Divide

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

2/5/2019

Student protestors surround Nicholas Christakis (right), a college master at Yale in November 2015

A specter is haunting academia – the specter of progressivism. It sweeps in like a wind, toppling statues, drawing new lines in the sand, and ripping away tradition and status to reveal (or so it claims), the oppression beneath.

It’s a revolution, some call it, and like many revolutions it has little tolerance for those who don’t conform to its new orthodoxy. At Middlebury College radical leftist students shut down a talk by social scientist Charles Murray because they didn’t like his ideas on race and IQ. At Berkeley they forced the cancellation of a talk by conservative writer Ann Coulter. At Evergreen State College they disrupted the class of a professor who challenged a call for white people to temporarily absent themselves from campus. At Yale they rounded on a college master and his wife (both also professors), and demanded their resignations for saying that students should dress as they please for Halloween. On these campuses, and many others across the US, the UK, and Canada, the specter of progressivism advances.

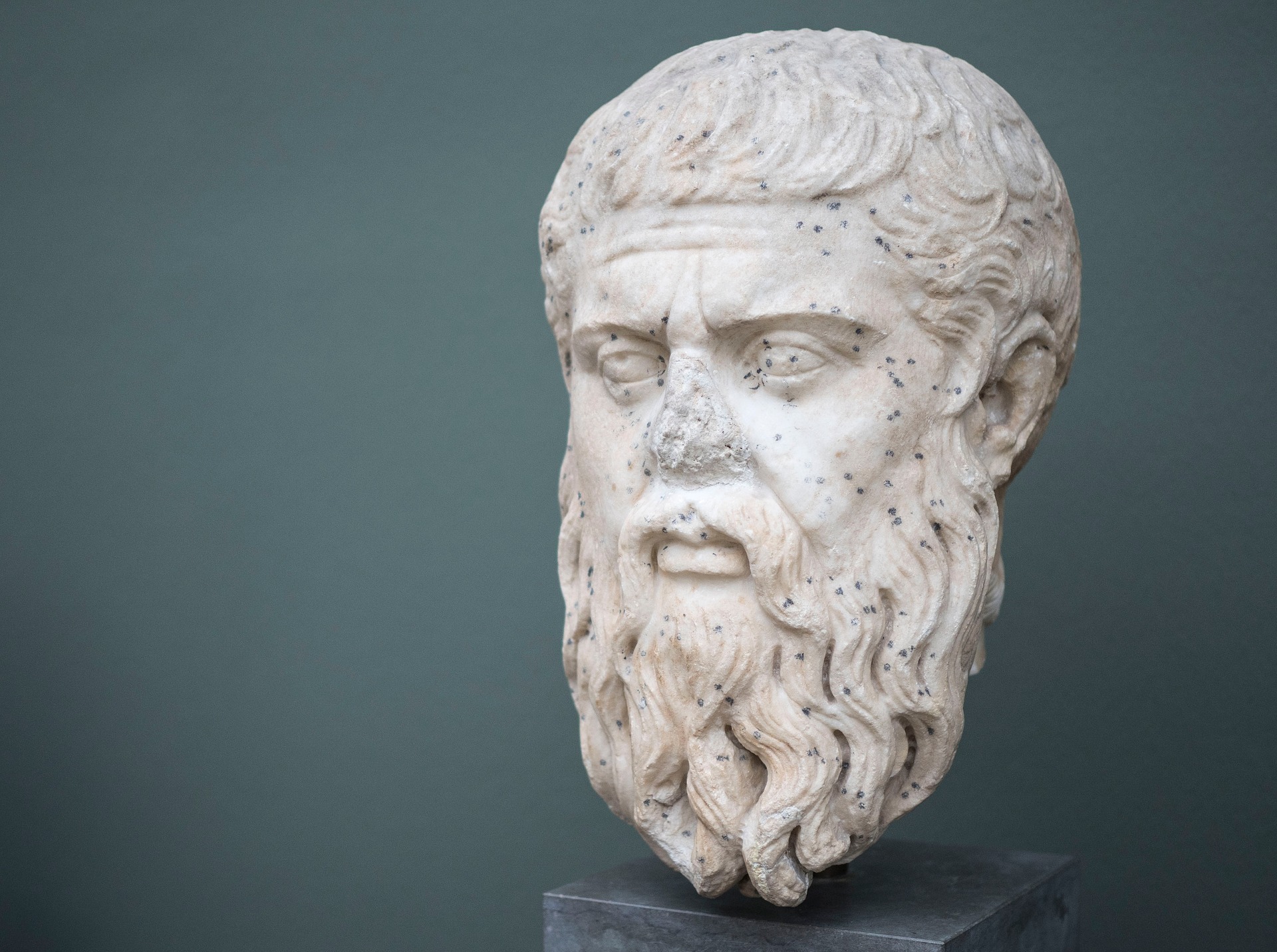

The new Red Guard takes a particular interest in tearing down idols, and no one seems safe from their bloodlust, not Plato, not Nietzsche, not Livy, not Shakespeare – in fact it seems the more established someone is the more likely he or she is to be attacked, that for the last to be first, the first must be last. At the University of Manchester, students objected to an inscription of Rudyard Kipling’s “If” on the grounds that the poet was “racist and imperialist,” and painted over it with “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou. At universities in the UK, a student-led campaign called “Why Is My Curriculum White?” aims to “decolonize” syllabi, to rid them of what it sees as the oppressive overrepresentation of white authors. The Keele University Manifesto for Decolonizing the Curriculum says “male, pale, and stale” curricula cause feelings of “isolation, marginalization, alienation, and exclusion” in students of color, and there are similar movements in the US pushing for the excision of “dead white males” from reading lists.

But who will they replace them with? It’s one thing if the new syllabi feature diverse and groundbreaking literature, but the radical left has a worrying tendency to obsess over victimhood and grievance, and to replace white males with women and people of color, not because they’re the best writers on the subject, but just because they’re women and people of color. “I’m here to teach resistance, one book at a time,” wrote Yvette DeChavez, who taught American literature, in the Los Angeles Times, “I wanted to create an American novel syllabus that skipped over the white dudes and instead privileged the voices of indigenous and people of color writers.” Dan-el Padilla Peralta, a left-leaning classicist at Princeton, called this “reparative epistemic justice.” “[W]hite men will have to surrender the privilege they have of seeing their words printed and disseminated,” he said. “They will have to take a back seat, so that people of color, and women, and gender non-conforming scholars of color benefit from the privileges, career and otherwise, of seeing their words on the page.” Why does this sound just like reverse discrimination, like some sort of affirmative action for the humanities?

One can know something about the tree from the fruit it bears. The Sokal Hoax of 1996 and the Sokal Squared Hoax of 2018 demonstrated the laughably low standards of some ostensibly serious peer-reviewed left-leaning social science journals. These hoaxes involved writing deliberately nonsensical articles (which nonetheless fit with leftist ideology), and getting them accepted by those journals. One of the articles in the latter hoax involved “canine rape culture at a Portland dog park,” another suggested binding “privileged” students to the floor with chains.

The progressives claim they are building a paradise, but why is this paradise filled with crippling insecurity, with the heckler’s veto, with reverse racism, with the lowering of standards or the outright denial that standards exist? Why do leftists so often respond to dissenting voices not with reasoned argument but with calls for them to be muzzled, or nonsensical slogans like “Believe survivors,” or ad hominem demands to “Check your privilege?”

***

What of the premises at the core of the radical left?

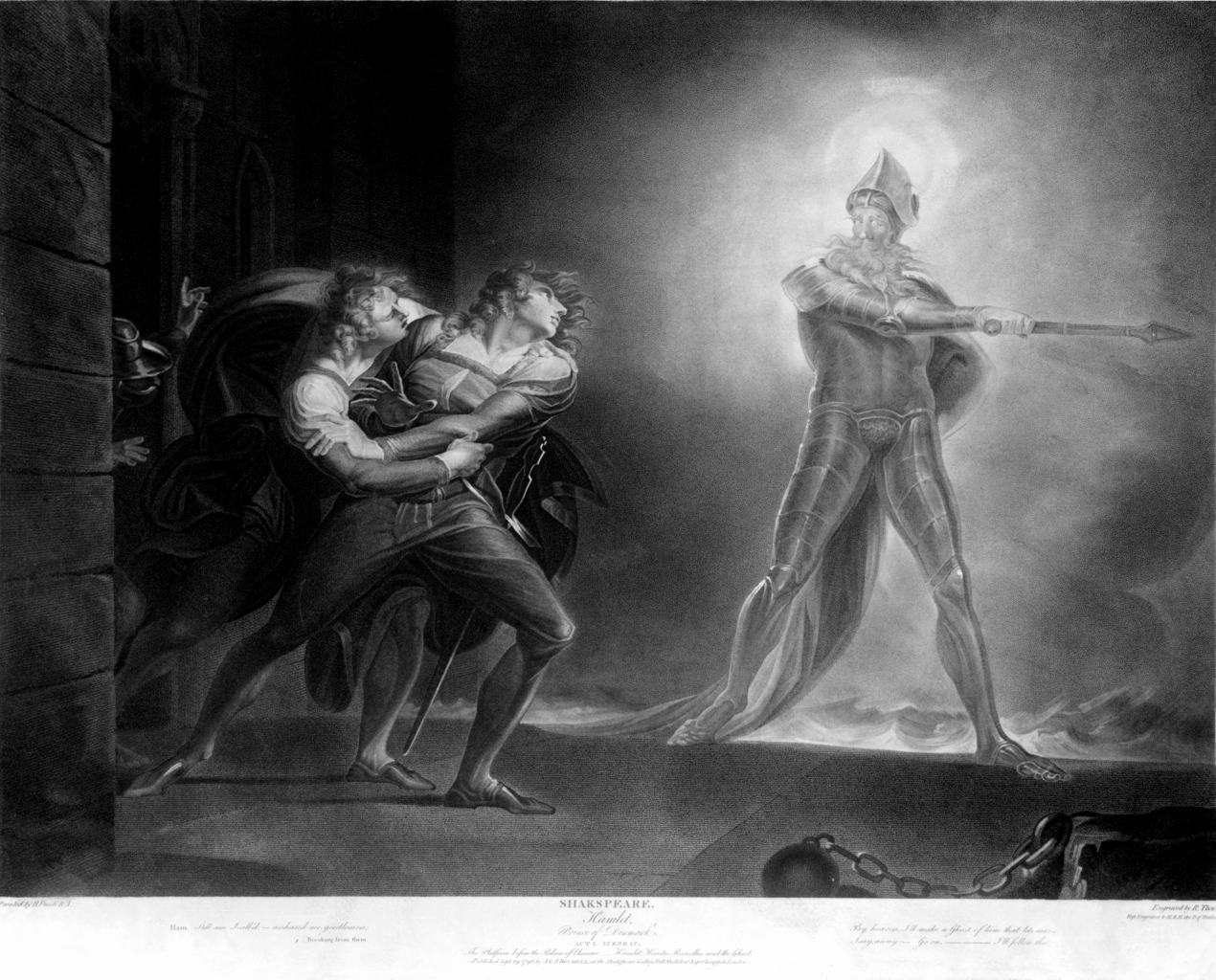

Its obsession with race, gender, and sexual orientation, and its insistence that these things should take precedence over merit is racist and sexist itself, and a betrayal of Martin Luther King’s dream for people to be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. “Decolonize the curriculum asks us to make decisions about knowledge based on biology rather than on intellectual merit,” wrote Joanna Williams in openDemocracy. “Instead of looking at what Hegel or W. E. B. Du Bois, Audre Lorde, or Sylvia Plath, have to offer in terms of their contribution to knowledge, we are asked to make crude judgments based on sex and skin color with white and male being bad, black and female being better.” The authors progressives assail are included on the curriculum not because they’re white or male, but because they’re good, because few can match the lyrical beauty of Homer, or the crisp brilliance of John Stuart Mill, or the wild wit of Oscar Wilde, because few can depict triumph and tragedy like Plutarch and Shakespeare. “I know Shakespeare’s a dead white guy,” said Mr Morgan, the black schoolteacher in the movie 10 Things I Hate About You, “but he knows his shit.”

“I know Shakespeare’s a dead white guy, but he knows his shit.”

You tell ‘em, Mr Morgan

In claiming that minorities don’t learn as well from events that took place in the West, progressives also misunderstand the nature of education. The study of, say, Thucydides’ history of the Peloponnesian War is important not because it tells us that two ancient Greek city-states fought each other from 431-404 BC, but because of what it teaches us about (amongst many other things) war’s effect on a society, a lesson that’s valuable to students no matter what country or ethnicity they hail from.

The claim that minorities have trouble relating to Western writers or characters, or anyone from a different background, is similarly dubious. I’m of Chinese ethnicity, and I happen to feel a strong affinity with Jia Baoyu, the curious and idealistic male lead in Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber, but I also relate to Hamlet, the dark and volatile prince of Denmark. Indeed, if education is the passing on of knowledge and wisdom from person to person and generation to generation, then the progressive position reveals a mistrust of the project of education as a whole. “To argue that ‘universal truth’ is a myth and that truth is context-dependent is to give up on the goals of education entirely – we have simply nothing to learn from previous generations or from each other,” wrote Williams. “We can only indulge in the narcissistic enterprise of exploring our individual truths within our personal context.”

Also illogical is the claim that a certain author should be removed from reading lists for being a bad person (usually because he was part of “the patriarchy” or allegedly racist or sexist). Even if, for the sake of argument, we accept that an author really was as morally reprehensible as his detractors claim, how would that affect the merits of his work? Would it make his ideas less significant, his insights less astute, his writing less eloquent? Could we not condemn him as a man, yet appreciate him as a thinker or stylist?

In calling for these changes to the syllabus in the name of inclusivity, the radical left also misunderstands the nature of colleges and universities. Colleges and universities, especially elite ones, are not and were never meant to be inclusive – in fact, some of them are amongst the most exclusive institutions in the world. Ivy League universities, for example, pick their students, faculty, and administrators largely because they’re supposed to be the best – and this elitism and exclusivity is part of their cachet, a cachet they (and often their students) tout by boasting of their low admissions rates. They’re committed to giving their students the best education possible, and to do so they need to use the best materials – regardless of who produced them.

Harvard, with its 4.5% college admissions rate, isn’t really meant to be inclusive

***

Is it any surprise, then, that the keepers of Western civilization in schools so stubbornly defend their heritage against the specter of progressivism? Much of their defense seems not so much a defense of Western civilization specifically than a defense of merit and standards.

If we are to speak of merit, though, some Eurocentric academics have been known to disregard it if it comes from another tradition. Eugene Sun Park, a former philosophy PhD student at a university in the Midwest, related that when he tried to push for more intellectual diversity in his department (including the hiring of experts in Chinese and feminist philosophy) he was basically told by one department member “This is the intellectual tradition we work in. Take it or leave it.” When he tried to introduce non-Western philosophy in his dissertation, a professor suggested he transfer to the Religious Studies department or some other department where “ethnic studies” would be more welcome.

Most times, however, Eurocentric academics don’t seem to reject literature from other cultures – they’re just ignorant of it. When I was a student at Yale, the professors who didn’t know much about parts of the world outside the US and Europe didn’t pretend that they did. “I was completely ignorant of that,” the classicist Donald Kagan, one of my teachers, said when I told him about race and society in Southeast Asia, “I knew nothing about it.”

No one can know all things, of course, but some prominent Western thinkers in times past had far better knowledge of and appreciation for the East. In his article, “Western philosophy is racist,” Bryan W. Van Norden, head of philosophy at Yale-NUS College and author of Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto, described how the German polymath Christian Wolff (1679-1754) was heavily influenced by Confucius and argued that he demonstrated it was possible to have a system of morality not based on either divine revelation or natural religion. This made Wolff a villain to conservative Christians but a hero of the German Enlightenment. French economist Francois Quesnay (1694-1774) was influenced by Chinese philosophy and governmental institutions, particularly the rule of the sage-king, Shun, who he saw as a model for the laissez-faire system he propounded.

Christian Wolff, polymath, radical, cosmopolitan

Western professors of strategy (and even business leaders) have long recognized the value of Sun Tzu’s Art of War, which is as edifying as Carl von Clausewitz’s On War (and infinitely more readable), but that’s usually about it; Western academics are largely ignorant of the wealth of knowledge and ideas from other cultures on the very same issues they study. It’s a pity. Everyone knows about Mahatma Gandhi, of course, but not everyone knows that his philosophy of truth and non-violence is as intellectually rigorous as it is moral, and is invaluable to any student of politics. Frantz Fanon could not be more different from Gandhi in manner or the methods he prescribes (though he sees colonialism in a similar way), and The Wretched of the Earth reveals the caged fury in the heart of the colonized man, and would help Europeans understand their former empires. Amy Chua’s World on Fire shows why race matters and makes readers rethink democracy. In his Satanic Verses Salman Rushdie sings of the dangers of fanaticism as ominously as any Greek chorus. Kahlil Gibran’s writing is a spring of wisdom and beauty. Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber is a work of breathtaking loveliness and sharp social commentary. Tracing the fates of two doomed lovers amidst the decline and revival of a great house, it’s a meditation on the meaning of life and a bittersweet tribute to youth and youth’s end.

Scene from Dream of the Red Chamber, by Qing Dynasty artist Sun Wen

And then there’s Confucius. Far from the patron saint of Asian authoritarianism, as he’s so often made out to be by opportunistic Asian dictators and clueless Western commentators, Confucius actually counseled balance, reciprocal obligations between ruler and ruled, and stubborn integrity in the face of unjust authority, along with filial piety. Surprisingly, he sometimes displays an individualistic streak that would rival Henry David Thoreau’s, and his moderation is a refreshing counterpoint to the extremism of his Western counterpart, Plato.

These are just a few examples from the texts I happen to be familiar with, of course. There’s plenty more where that came from.

***

In Beyond Liberal Democracy: Political Thinking for an East Asian Context, Daniel A. Bell, dean of political science and public administration at Shandong University, related his experience teaching political theory at the National University of Singapore. When he included a Chinese thinker in his syllabus, he was surprised to discover that this led to hate mail and “strong dissatisfaction” among minority Malay and Indian students. The following year, he included contributions from Islamic and Indian thinkers, leading to greater class satisfaction.

“The lesson, of course,” he concluded, “is that the teacher should make an effort to design a curriculum that draws on the scholarly contributions of all ethnic groups in the class.”

Despite his undoubtedly good intentions, he seems to have learned a false lesson. If the contributions from Malay and Indian thinkers had more merit than some of the other items on the syllabus, then he should have included them solely for that reason, not because of inclusiveness for inclusiveness’ sake, and certainly not because of hate mail and pressure from students. The role of a teacher is to challenge his students with the most eloquent, most significant, and most intellectually rigorous texts, not to please them.

The role of a teacher is to challenge his students, not to please them.

The writers I mentioned in the preceding section, however – and no doubt many others that I’m ignorant of – could easily be included in syllabi in schools in the West for no other reason than that they’re incredibly good. This seems to be the approach taken at Yale-NUS College in Singapore, which teaches the Ramayana alongside the Odyssey in literature, Sima Qian alongside Herodotus in history, and Mencius alongside Aristotle in philosophy. Teachers in the West owe it to themselves, their students, and their own disciplines to learn about these texts and to include them in their courses whenever appropriate. Not because of diversity or inclusiveness or some feeble cultural relativism or that cliché that we “live in a globalized world,” but because good ideas don’t recognize borders. Because there are universal lessons and some can be found in other cultures. Because nothing human should be alien to the humanities, and the more kinds of humans you understand, the better you understand human nature. Because you cannot understand an issue if you remain ignorant of the rest of the world’s literature on it.

Scene from the Ramayana

Even after widening their scope, of course, most of the writers and thinkers Western teachers include in their syllabi may well still be white, but what are the chances that all of them will be? And when they do include non-white names on the curriculum, they’ll be doing so not as a sop to progressives, but because they genuinely think it enriches an understanding of an issue.

This argument appeals not to a sense of inclusiveness but a sense of elitism. Every teacher worth his salt should try to ensure that the texts used in his class are the best – the best in the world, in fact. But how to know if they really are the best in the world without some familiarity of what’s in the rest of the world?

“Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus, the Proust of the Papuans?” the writer and Nobel Laureate Saul Bellow once asked, in an apparent jab at the progressive agenda. “I’d be happy to read them.”

He received a lot of flak for that, for implying that the Zulus and the Papuans hadn’t produced a literary genius, and, indeed, that some cultures might have produced more genius than others.

Less attention, however, is paid to his second sentence: “I’d be happy to read them.”

What that means is that whilst he was ignorant (or maybe even skeptical) of a Zulu or Papuan genius, he was open to learning about and recognizing one.

If he was indeed sincere in that assertion, that seems a good approach to take – openness to other cultures without relaxing your standards. Brilliance is rare enough that no one who cares about his or her field can ignore it – whether it comes from a Zulu or a dead white man.