Faking It

By Shruti Kothari

Staff Writer

20/6/2019

I was recently tasked with interviewing a fashion designer for the cover story of a magazine (not this one). Oddly enough, she had emailed the publisher and asked to be featured; this request was fortified with a stacked resume, which included working with various celebrities, features in other prominent publications, authoring four bestselling books, and a TEDx talk on how all body shapes were beautiful. Sold, we promised her the article. A few days later, I was balancing six of her outfits like a human hanger, and asking her questions as she smiled for the company photographer.

Between my questions, she kept repeating the same thing: “Whatever you do, Shruti, please promise me that your team will Photoshop me to look thin. I’ve been writing a memoir and so I’ve put on weight these last six months, but I don’t normally look like this.”

Given the subject of her TEDx talk, I found this attitude confusing. She then started to say things like, “I’ll Instagram this photo shoot, it’ll really give your magazine a boost. You know, yesterday I ate at a restaurant and tagged them, and today they’re completely booked out. Because I tagged them.”

Alarmed, I surreptitiously started to research her as the afternoon wore on. She had 79 followers on Instagram; even if they all flew in from across the world and congregated at this restaurant, it would have been half empty to an optimist. Her books were on Amazon, but the publishing house was eponymous; it was her own. Moreover, each of her books had twenty-ish reviews, all five stars. Were these written by friends or employees, I wondered? Even with the perfect ratings, her works lay somewhere beyond the #1,000 top-ranked books; certainly not bestsellers, then. The further I delved into her story, the more evidence I gathered that she was, in fact, a con artist.

The further I delved into her story, the more evidence I gathered that she was, in fact, a con artist.

I legged it back to the office straight after, and divulged my revelations to the publisher. He was stunned, but that didn’t matter: we were stuck. We couldn’t possibly put her on the face of our publication, but we were held hostage by our own word. We had guaranteed her an article, so no matter what we did, our integrity was compromised. I could have written to her and told her I thought she was a fraud, but I didn’t have it in me. She was in her sixties, all dentures and leathered skin, and she’d told me stories about how her life had been fraught with domestic abuse and family betrayal. Who knows if any of it was true, but I kept thinking of Tennessee Williams’ Blanche DuBois. What if this lady was genuinely delusional, some subconscious defense mechanism to avoid an unpleasant reality, and by accusing her I tore down her entire world?

In any case, although she will never be on the cover, she will certainly have a page or two inside within the next few months. What’s amazing is that she has enough honest achievements to write a decent piece about — one of her dresses appeared in a TV show fifteen years ago, for example. Though perhaps she scored that gig by persuading the producers that her clothes sold like hotcakes. Once her article is published, she will have even more ammunition to prove to others that she’s a smashing success, in a magical upwards spiral where sheer conviction leads to the manifestation of her desires. She talked about Bob Proctor and Jack Canfield being her close friends; these popular motivational coaches often encourage strategies like she uses, where if you believe something enough, it shall come true.

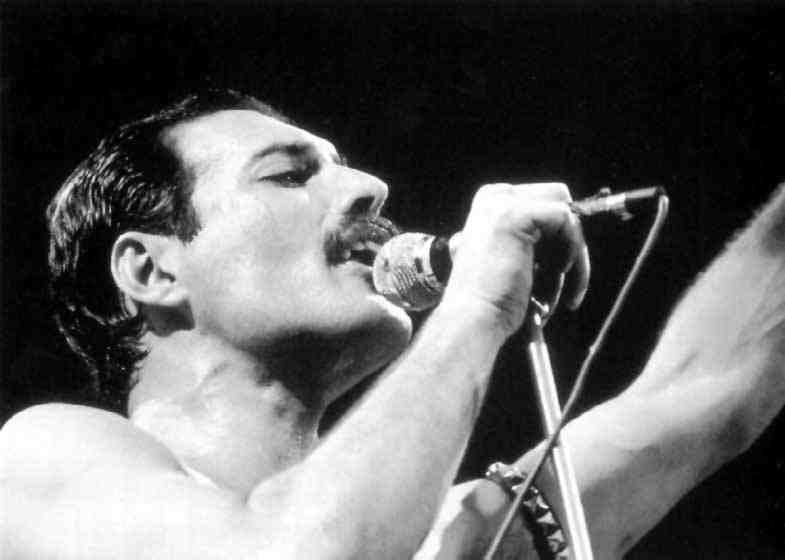

I have nothing against having strong belief in oneself. Disruptors are vital for progress in any field. For example, Freddie Mercury had an unshakeable faith in his own music, and success followed that absolute certainty; the industry changed because of it. Picasso’s radical experimentation made him one of the fathers of modern art. Without single-minded drive and self-confidence, they would never have made it big the way they did. However, both of these figures possessed incredible amounts of talent to back their clarity of vision; there was no deception of any kind, just forward movement.

Freddie Mercury (Picture Credit: nikoretro)

Then there is the matter of wishing something unreal into existence. It’s not impossible: the existence of psychosomatic illnesses, or the efficacy of placebos, even when the patient knows they’re popping sugar pills, provides easy evidence of that. Philip Zimbardo’s famous Stanford Prison Experiment, where students assigned the part of either guard or prisoner internalized their roles so deeply that the experiment had to be terminated early, again shows that even though a person may be aware that something is a lie, being told it is true can make it true to some degree. In this case, again, there is no villain; all of the cards are on the table, so there is no real deception. Nonetheless, it can still have a large impact on a subconscious level, and can be harnessed. For example, dressing smartly to meetings may automatically give you more authority in your eyes and in those of the beholder.

What about the case in which there is a clear liar, and someone is being duped? Restaurants will often pay people who have never eaten at their establishment to write positive reviews on TripAdvisor; people make a career out of providing such feedback. The truth is, it’s an effective and widely used method to increase your customer base. Journalist Oobah Butler, armed with a burner phone, fake food photographs and sham reviews, turned his shed into the #1 restaurant in London on TripAdvisor within six months of “opening,” all without cooking or serving a single meal. When he finally hosted a dinner, he served ready meals presented and garnished differently, and diners lauded the creations as spectacular. It was a win-win situation, where guests felt they had experienced an exclusive, exceptional dinner, and Butler could have taken money from them and perhaps even sustained the restaurant for some time. He didn’t, of course. He shut down the operation and used the information for an article, as planned.

It can be argued that modern-age villain Elizabeth Holmes, founder of Theranos, had noble objectives; she perhaps genuinely wanted to develop technology that allowed blood tests to become cheaper and more efficient, thereby improving medical accessibility, especially for lower income individuals. Her company reached a $10 billion valuation at some point; she was acknowledged as the youngest female self-made billionaire. Investments were based on fudged facts, non-existent machinery, and the all-star cast Holmes invited to join the board of the company. Holmes herself was convincing — aside from adopting a deepened voice and wearing black turtlenecks reminiscent of Steve Jobs to appear more trustworthy, she seemed so sure about her ability to perform that big corporations threw millions of dollars her way.

Elizabeth Holmes: Entrepreneur, master networker, fraud

The question is, at what point does this “Fake it ‘til you make it” mindset become truly unethical? Everyone loved socialite Anna Sorokin until she turned out to be fraudulent, but she became an object of fascination and intrigue, rather than actual loathing. Holmes wasn’t vilified just because she was revealed as a scammer. It’s true that if no one had found out, she may have remained a hero, so certainly her downfall was caused by her inability to remain undetected. However, what made her so reviled goes far deeper than that. Her deception involved taking large amounts of money from people, but also harming patients through inaccurate blood testing, and putting employees in such moral dilemmas that her chief scientist committed suicide from the pressure.

Her lies, and the death of the scientist, revolved around Holmes’ inability to deliver the goods. Even years of scamming may have been forgiven if she eventually did successfully invent technology for comprehensive testing that only required one drop of blood, as promised. If the journalist, Butler, were actually a good chef, then despite his murky beginnings, he may have sustained his fake restaurant to the point where it became a real restaurant with good food. Everybody would have been a winner. If anyone ever caught on to the lies, they may have even laughed about it, because they weren’t being personally or harmfully cheated.

Even years of scamming may have been forgiven if she eventually did deliver as promised.

Essentially, if you are planning to embellish the truth here and there, it’s best to make every effort to ensure it won’t come to light. It’s not a good look. If you do want to convince your neighbors that you’re an expert hairdresser, and they should let you snip their locks for half the price of a salon do, you’d better be sure you’re able to do a half-decent job. If not, back out before it begins, or there’ll be a much-deserved reckoning. Provide what you promised, and you’re safe.

If your discrepancies are discovered, be prepared for an accounting. What lengths did you go to, to protect your lies? Gaslighting or forgery? Make sure your ends can justify your dishonest means. For example, I’m sure the fellow who forged the Donation of Constantine has no regrets. This document was employed several times over centuries; for example, it was used to convince the Carolingian Emperor Charlemagne to endow lands and power upon the Pope, who, in return, crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor. Victories all around, and by the time the document was declared inauthentic, everyone involved in its conception was conveniently dead, and it had achieved its aim: more authority for the Catholic Church.

13th century fresco depicting purported Donation of Constantine

In “The Hunting of the Snark,” Lewis Carroll writes, “what I tell you three times is true.” The more we are told something, especially from reliable or varied sources, the more we begin to accept it, unless something tips us off. The protagonist in The Emperor’s New Clothes was content to walk around nude if it was an assurance of his wisdom. Everyone around him wanted so badly to believe that he was wearing a fabulous new outfit, that they might have spent the rest of their lives playing that game if an innocent child hadn’t pointed out that the ruler was, in fact, naked.

I don’t know if I’m willing to take on the role of that child when it comes to the woman I interviewed. When I informed her that her feature would be delayed, she responded, “Ah, bummer! I had organized a party with my important American friends and influencers to celebrate it, and I really wanted to invite you, but even the best-laid plans go awry. Sorry you won’t meet them!”

Somehow, my rejection of her turned into a rejection of myself, and the combination of steel balls and fragile delusion it must have taken to write that response was weirdly admirable. It is something I am unwilling to shatter. Something about her makes me want to suspend my disbelief. Writing a kind article about her can only help boost her questionable career, at no cost to myself or anyone else, really. While her prose isn’t great (I barely made it through a page of one of her books), her designing isn’t bad. I will become an accomplice in her performance, partly because her acting wasn’t good enough to land her a solo, but largely because I’m curious to follow her story and see how far her attitude gets her.