Kings of New York

By Lisa Yin Zhang

Staff Writer

21/5/2020

Picture Credit: Marc A. Hermann (Cuomo), Gage Skidmore (de Blasio)

I thought about finally watching The Sopranos this quarantine, but what’s the point, when I can watch a real-life high-stakes Italian-American feud unfold before me?

I’m referring, of course, to the very public feud between New York State governor, Andrew Cuomo, and New York City mayor, Bill de Blasio. The two prominent Democrats have duked it out over issues ranging from public housing, workout routines, homelessness, taxation, the subway, the euthanizing of a single social-media-star deer, and napping. “If someone disagrees with him openly,” de Blasio has said of Cuomo, “some kind of revenge or vendetta follows.” Likewise, an insider in the Cuomo camp accused a de Blasio-backed primary challenger of being “an outgrowth of the mayor’s vendetta against the governor.”

The fact that this feud is playing out before a captive audience of eight million sheltering New Yorkers with far too much free time has only intensified it. And New Yorkers haven’t been coy about who they favor.

The fact that this feud is playing out before a captive audience of eight million sheltering New Yorkers with far too much free time has only intensified it.

“Cuomo isn’t holding me hostage so much as coronavirus is, but he is the only one telling me…where I can and cannot go (anywhere), who I can and cannot see (everyone), who I can and cannot listen to (President Trump, Bill de Blasio),” swooned a journalist at Jezebel, “I think I have a crush???”

Meanwhile, a Buzzfeed article noted, dryly, “Everybody’s Having A Great Time Hating De Blasio.” “Until Cuomo says anything, I don’t trust what DeBlasio says!” wrote a Reddit user, whilst another described the mayor as “Tepid” and “Flaccid.”

How did it come to this? What are the roots of this feud, and why has Cuomo’s performance during the COVID-19 crisis been praised while de Blasio’s has been derided?

Picture Credit: Sam valadi

Andrew Cuomo, born and bred in New York, was the eldest of five children, the son of the legendary liberal New York governor Mario Cuomo, and came of age in the Clinton era of the Democratic Party. He was always combative. In the 80s, first as head of his father’s transition committee and then as an advisor, he was notorious for strong-arming politicians on his father’s behalf. In the 90s, as the Clinton administration’s Housing and Urban Development secretary, he fought with HUD’s inspector general. Across his career, he’s sparred with former governors Eliot Spitzer and David Paterson, Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, and Michael Bloomberg, de Blasio’s mayoral predecessor.

Described once as “a political tactician of almost limitless ambition and extraordinary ability, a leader with jagged edges and little regard for rules,” those who know Andrew Cuomo intimately say his approach to power is zero sum: the more anyone else has of it, the less remains for him. His view on progressive governance? Too much poetry, not enough prose. He bills himself instead as a progressive “not just in words,” successfully passing marriage equality, raising the state minimum wage, cracking down on gun control, instituting family leave, expanding reproductive health, and developing infrastructure. “Bernie Sanders [wants] free college tuition,” he said. “Did it! Fifteen dollar minimum wage? Did it!”

Those who know Andrew Cuomo intimately say his approach to power is zero sum: the more anyone else has of it, the less remains for him.

Bill de Blasio, on the other hand, grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, studied at NYU and Columbia (contrast to Cuomo’s Fordham U and Albany Law), and, at 26, went to Nicaragua to help the Sandinistas distribute food and medicine (at the same age, Cuomo was working in his father’s gubernatorial campaign). His own father was no role model: an alcoholic, he divorced de Blasio’s mother early, and committed suicide a decade later. In marked contrast to Cuomo, who cites his father as a paragon and views his accomplishments as a goalpost, de Blasio took his mother’s maiden name.

He began his career in David Dinkins’ mayoral campaign in 1989. In the 90s, he was the regional director of the Department of Housing and Urban Development — appointed, in fact, by then HUD secretary Andrew Cuomo. De Blasio went on to win his first government seat, as a city council member, in 2001. He displayed a streak of vindictiveness even then: “If you’re not with me for speaker,” he told a fellow council member, “I’m against you in anything you do, ever.” (He lost.) In 2009, he was elected public advocate. And in 2013, due largely to the meteoric fall of clear favorite Anthony Weiner, de Blasio was elected mayor of New York City by a landslide 49-point victory.

“If you’re not with me for speaker,” de Blasio told a fellow council member, “I’m against you in anything you do, ever.”

But Cuomo didn’t endorse de Blasio until he was already the presumptive Democratic candidate. That day, at, ironically, a unity rally, Cuomo’s and de Blasio’s aides got into a vicious argument about the speaking order. It was de Blasio’s day of glory — but Cuomo, always the alpha male, spoke for longer. Then, on July 17, 2014, Eric Garner, an unarmed black man, was killed by police. When a jury failed to indict the New York Police Department officer, the city erupted in protests. Weeks later, two officers were killed in revenge. Dozens of NYPD cops turned their backs on the mayor at the officers’ funeral because of his perceived failure to support them during anti-police protests. Cuomo offered little support. “There are so many ways for you to be both a responsible actor and a good friend,” said a close friend of de Blasio, “and he did none of them in that moment.”

Understanding why New Yorkers so overwhelmingly favor Cuomo, though, requires insight into the New York psyche. As former Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen put it: “New Yorkers are incredibly tribal and proud and think they’re the greatest people in the world, and they think New York is the greatest city in the world, both of which happen to be true.”

New Yorkers seem to demand leaders who are as chauvinistically proud of their city as they are. This is doubly true in a New York rocked by crisis, a New York with Broadway dimmed; a New York without museums, or restaurants, or even the subway. Slowly, we’re seeing New York build a new identity: we applaud essential workers as a city each day at 7 pm, for instance. And some traditions, like irascibility, never die: someone attempting to replicate the lovely Italian quarantine tradition of singing opera from their balcony was met with a very loud, very New York, “Shut the fuck up!” Memes documenting stubborn, asshole-ish New Yorker-ness abound. The narrative of what it means to be a New Yorker — resilient, fiercely proud, maybe a bit of a prick, probably a little miserable, mixed in with something redeeming — is more important than ever before, as the city is pummeled by the pandemic.

Picture Credit: absolutewade

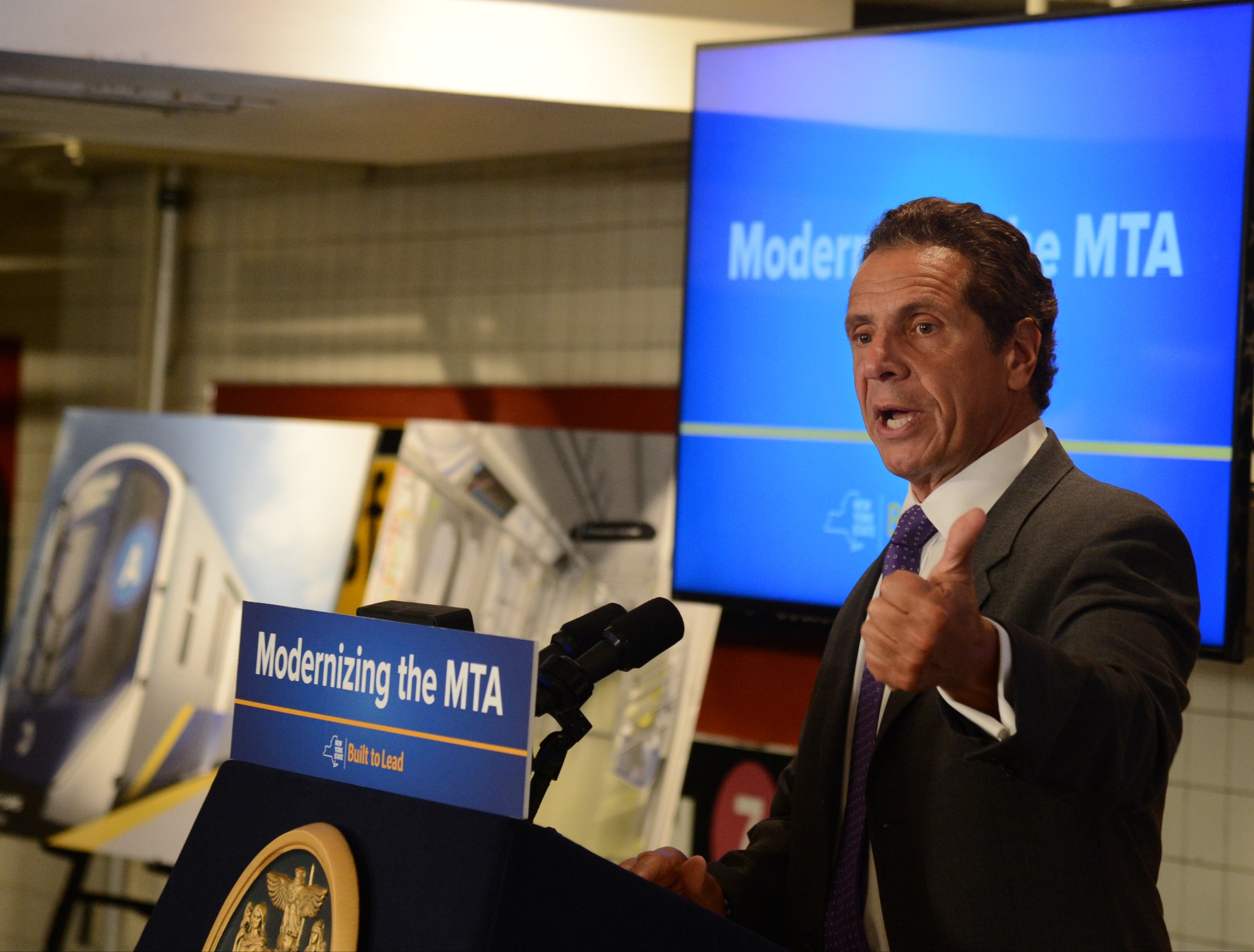

With his lined face, dark, curly hair shot with gray, characteristic glower, and distinctive Queens Italian drawl, Governor Cuomo fits in well with that gritty narrative. He has been frenetically busy in recent weeks, waking as early as 4:30 am to review COVID-19 briefings. When asked what he’s doing for fun, he replied that he was signing bills to make New Yorkers’ lives better — “And that’s enough,” he insisted. He loves all things New York. He can be found haunting his local Dunkin’ Donuts, and his hobbies include fishing, zip-lining, and generally hanging about New York State. Like his father before him, he’s known to travel hundreds of miles to avoid spending a night away from the state. “I am happy doing what I do,” he told a Politico reporter recently, then paused to think. “Not happy, that’s the wrong word. Happy-ish…Well, it’s hard, right?”

Cuomo (Picture Credit: Metropolitan Transportation Authority of the State of New York)

De Blasio, on the other hand, seems to sometimes embody the bumbling side of the progressive wing of the party. Once, at a rally in Miami, he got excited and shouted “Hasta la victoria, siempre!” the rallying cry of Che Guevara, whom Florida’s Cuban exile community detests. “The left has some people that are just clueless as hell,” grumbled State Senator Annette Taddeo. Most damning of all, he didn’t grow up in New York, and can appear to adore it less than he should. “He may be the first mayor of NYC to speak without any trace of a New York accent,” said linguist Daniel Kaufman. He has a lopsided smile that sometimes looks like a sneer, and, to the outrage of many, he eats pizza with a fork and knife. He’s a Boston Red Sox fan. And, of course, he ran for president, thus insulting New Yorkers by implying there’s a higher post than Mayor of New York City (76% of New Yorkers were against his bid). It didn’t help that he was out campaigning in Iowa when a blackout swept the city, and that he hesitated about returning to deal with it. (By the time he got back, the power was already back on.) This has all served to estrange the mayor from his people. “The New York mayor turned quixotic presidential candidate seems sick of his city,” observed Matt Flegenheimer in the New York Times, “and the feeling is mutual.”

De Blasio at the 2019 Iowa Democratic Wing Ding, a fundraiser (Picture Credit: Gage Skidmore)

The media factors in too. Cuomo’s popularity is buoyed by his cosy relationship with the press. There’s obviously his brother, Chris Cuomo, whose CNN show he frequently appears on, but also a years-long amity with New York Post reporter Fred Dicker (which has since cooled). He’s earned such a reputation for prattling on to the press, often on irrelevant tangents, that the New York Times once threatened to bar its reporters from talking to him off the record. De Blasio, by contrast, has a notoriously poor relationship with the media. He seems to take their haranguing — a New York City mayoral ritual — deeply personally: “You don’t understand,” he told one of his staff once. “They hate me.” It’s an open secret that he’s rooted for the downfall of tabloids, once emailing his aides in response to rumors of firings at The Daily News: “That would be good for us, right?” The press has returned the favor. Reporters tweet their frustration when he’s late to events, leading to the widespread notion that de Blasio is tardy, lazy, and disorganized. “DE BLASIO MUST GO!” read one New York Post headline last summer.

The COVID-19 crisis has only widened the popularity gap. Governor Cuomo is an excellent communicator. He has been both straightforward and meditative, explaining complicated systems of decision-making, whilst at the same time going on weirdly relatable little tangents: “My daughter, you know. That’s everything to me. That’s why I get up in the morning. How could I protect my daughter?” Due in large part to this, he’s been lauded for his handling of the pandemic. Even his critics have praised his performance. Nicole Malliotakis, a Staten Island Republican congressional candidate, said, “I do believe that during an emergency situation he is at his best.”

Mayor de Blasio is a bit of a ham. His daily press briefings teem with soaring rhetoric and barrages against President Donald Trump, passé to New Yorkers who’ve heard it all before and simply want their lives to get better. I tuned in recently to him brandishing a New York Post cover: “What kind of human being sees the suffering here and decides that people in New York City don’t deserve help? What kind of person does that?” he demanded. He’s been seen as vague and vacillating: clashing with his own health officials, closing schools too late with too little preparation, more comfortable raging against Trump in Washington than fixing problems at home. The optics aren’t good: not a day after (finally) issuing a stay at home order, he was seen at his beloved Brooklyn gym (which is in a different borough from his house).

“It’s not just what you’re communicating. It’s how you’re communicating it,” Rebecca Katz, a former de Blasio aide, said. “And Cuomo fundamentally understands this in a way that de Blasio frankly refuses to.” It’s true: narrative matters. But it’s not the only thing that matters. We should be wary when narrative diverges from the facts.

Narrative matters. But it’s not the only thing that matters. We should be wary when narrative diverges from the facts.

While de Blasio has gotten most of the flak for New York City’s coronavirus situation, both men are responsible for what can only be called a shitshow of a governmental response. In early February, Mayor de Blasio said of the coronavirus: “this is not something that you’re going to contract in the subway or on the bus.” On March 2nd, Governor Cuomo said, “Excuse our arrogance as New Yorkers — I speak for the mayor also on this one…We don’t even think it’s going to be as bad as it was in other countries.” For days after the first positive test in New York, both Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio and their offices projected confidence; for weeks, they failed to take aggressive action. “We’ll tell you the second we think you should change your behavior,” said de Blasio on March 5th. Then, when the mayor finally told New Yorkers they should change their behavior, the governor resisted, favoring a more gradual shutdown. “I’m as afraid of the fear and the panic as I am of the virus, and I think that the fear is more contagious than the virus right now,” Cuomo said. COVID-19 hit black and Latinx people in New York City hardest. Manhattan, the densest borough — but also the richest, and whitest — reported the lowest rates of infection. When social distancing guidelines were put into place, police closed one eye to packed parks in cramped downtown Manhattan, whilst relentlessly patrolling the largest, most sprawling park in the city, in the heavily brown and black Bronx. But both the governor and the mayor have insisted they had no regrets about their handling of the pandemic.

The Bronx (Picture Credit: dreig)

Furthermore, what reporting on the de Blasio-Cuomo feud often neglects is that whatever antipathy exists between the two men is only partly personal. In many ways, it’s only the logical result of the structural failings of New York state governance. In de Blasio’s own words, “Where you stand is where you sit. Rockefeller and Lindsay, Koch and Cuomo, Bloomberg and Cuomo — this is not a news flash. There’s a natural tension between mayors and governors that’s quite profound.” Due to a vast bureaucracy, and vestigial pieces of legal code — the state’s constitution is around seven times longer than the federal one — mundane aspects of city life, like applying for a liquor license or instituting a red-light camera, have to go through the state’s capital, Albany, two and a half hours north. On the other hand, New York City, though technically under the jurisdiction of the state, is far more of a cultural and economic powerhouse, and the mayor of the city typically upstages the governor of the state. This system sets the stage for constant boundary disputes and friction and sparring.

Finally, dominant media narratives often overlook a large slice of New Yorkers. While de Blasio’s poll numbers have plummeted with liberal white people, he is still very popular with black voters, who often have no love for the mainstream news media: 31% of white voters approve of him, and 58% disapprove, whilst 66% of black voters approve of him and 23% disapprove. Liberal white people’s dislike of de Blasio is so strong that it can even override the facts: while crime has fallen during de Blasio’s tenure as mayor, some white voters believe it has risen. “If you are a person on the Upper East Side or the Upper West Side — or the Times’ newsroom — your perception of de Blasio is a mirror image of what people of color think,” Peter Ragone, a former aide to de Blasio, said. “You know what people of color love? Jobs and not getting frisked by the cops.” Some criticisms leveled against de Blasio, like his purported laziness, are tropes often used against African Americans. Because he’s an advocate for those constituencies — and husband to a black wife and father to a biracial son — some allege that those racist stereotypes are applied to him by extension.

Believe that, or don’t. But consider it carefully. In this tale of two cities, if you’re lucky enough to remain gainfully employed, to still have the time to read think pieces like this one, then the least you can do is try to look beyond the spin and the optics, beyond de Blasio’s faux pas and Cuomo’s cute repartee with his brother on CNN. The true measure of a leader, after all, especially in a time of crisis, depends not on having the best narrative, but on ensuring the welfare of your people.