Living with the Dead

By Shruti Kothari

Staff Writer

27/10/2020

Thai people securing blessings at Wat Chedi Luang, a Buddhist temple, in Chiang Mai

In 2013, the Bangkok Post published an article about a Thai Airways plane crash. The aircraft had mysteriously skidded off the runway; the Managing Director of Thai Airways said investigations revealed that “vengeful spirits” had caused the accident and had to be appeased. Many top officials in the aviation industry stood by his statement and agreed that Suvarnabhumi Airport was plagued by a large number of such spirits which had caused countless other incidents, like worker deaths during construction, and demonic possession. This came as no surprise to local readers – the airport had been constructed on an old graveyard, and while 99 monks had chanted to appease the ghosts of the dead denizens, it made sense that some were still upset about the roar of planes disturbing their rest. Certainly, a long string of delays and bad luck surrounding Suvarnabhumi seemed to prove that.

What excited locals about the 2013 crash was not the haunting, which was expected, but an injured passenger who claimed to have been saved by an air stewardess in traditional Thai clothing. Members of the fire brigade and emergency response team had seen her too. The catch? None of the flight attendants onboard had been wearing traditional clothing. Did Suvarnabhumi have a guardian angel?

A few months later, when I returned to Bangkok from university, I was surprised to find that my old schoolfriend Top had been ousted from one of my social groups (incidentally, Top is a pilot). “He’s dating a ghost,” another friend, Pim, explained unabashedly.

When I returned to Bangkok from university, I found that my old schoolfriend had been ousted from one of my social groups for dating a ghost.

It took me a while to recover from my initial shock and piece together Pim’s story. Top, a notorious ladies’ man, the athletic kind you found sneaking out of the girls’ locker room on the regular, had finally settled on a girlfriend named Becos Cos. He’d immediately stopped drinking, quit smoking, refused to leave his house past 10 pm. Becos Cos was the complete opposite of Top’s usual model-esque lady friends: she was well-nourished, sported neon braces, and an average of six pompoms in her hair at any given time, judging by photos. Nobody had any mutual friends with her, nobody knew whence she’d sprung.

“What’s really weird,” Pim explained, “is that any time anyone asks Top how they met, he gets violently angry. He’s never answered.”

Wasn’t it possible, I asked, that there was some painful story he didn’t want to get into?

“I guess, but that’s unlikely. Anyway, that’s not all. Something else happened. I was at his house a few months ago, we were listening to music in the living room and my dad called about work. It was loud, so I walked towards Top’s room to get away from the noise. As soon as I set foot in it, my dad started yelling on the phone, that wherever I was, I needed to get out of there immediately. He said it was haunted. I jumped out and my dad immediately calmed down. It was like a switch. She’s done something to it. Maybe she was in there. Dude, nothing about her makes sense.” (According to Pim, her father sensed an evil aura and that she was in danger when she entered the room.) Pim visibly shuddered and touched an amulet under her shirt. “Just trust me and stay away from her.”

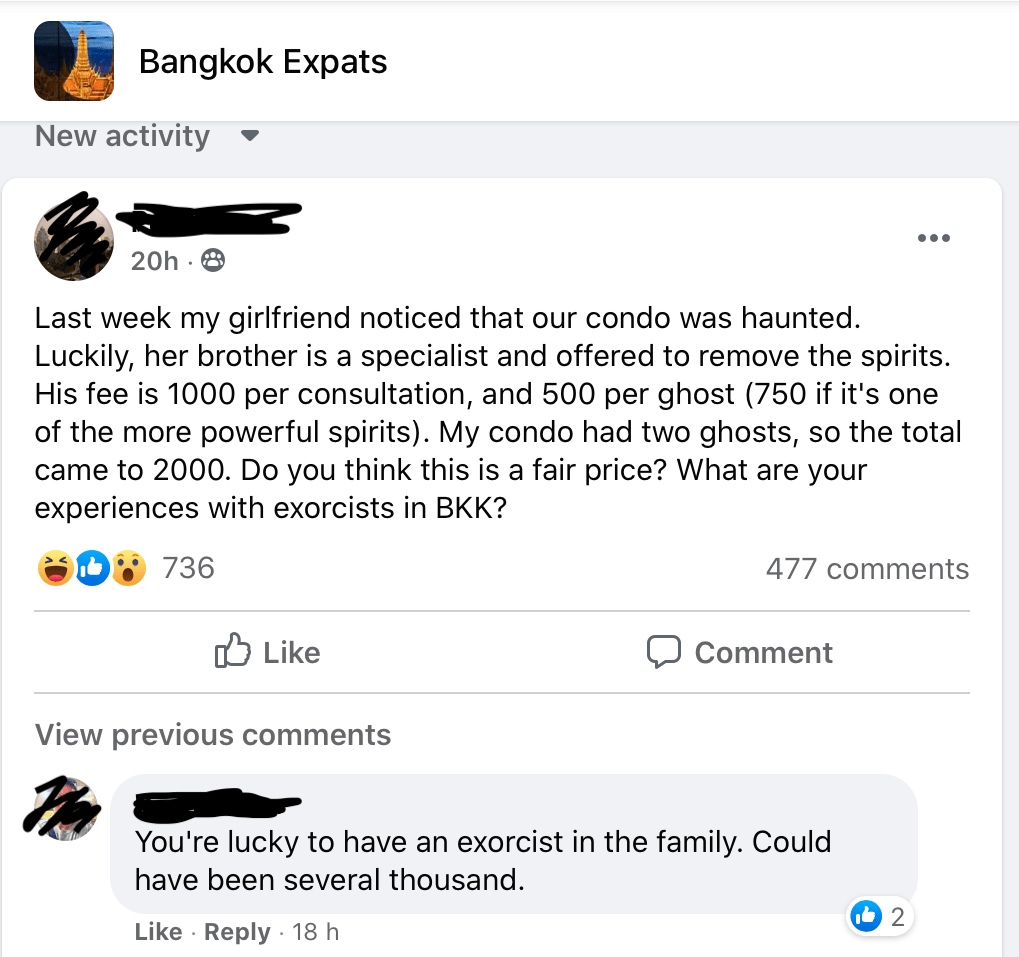

Imagine my outrage – and skepticism – when the results of a 2020 National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA) poll indicated that <6% of Thais seriously believed in ghosts. Beyond personal anecdotal experiences, which cover the spectrum between stodgy airport officials and trendy, internationally-educated hipster Thais, the evidence of strong, perennial belief is woven into our very identities. Common Thai nicknames include uan (fatty), lek (shorty) and gop (toad). Parents give these monikers to children to try to make them less attractive to evil spirits, but even if they don’t work, engaging an exorcist is a cheap and easy affair. You can report a haunting to the police, and they’ll send a task force to ghost-bust. Old Bodhi trees, revered for sheltering the Lord Buddha, also shelter powerful indigenous tree spirits; colorful brocade and satin strips wrapped around the trunks as offerings serve as visual reminders of the supernatural forces that shape the Thai psyche.

The Thai vocabulary contains a veritable cornucopia of words to describe ghosts with far more specificity than most other cultures. We have iconic named ghosts like Mae Nak, who has a very popular shrine and a largely agreed-upon mythology, but we also have subcategories of ghosts: phi chao kam nai wen, those who hold grudges against people who wronged them in life; phi ha, women who died in childbirth; phi tai hong, people who died violent or unnatural deaths and have a penchant for possessing others; phi ka arkom, those who violated traditions and were cursed. We even have phi hong nam or phi kee, who may be invoked when you are waking from a nightmare to defecate, to allow your bad luck to be flushed away alongside your excrement. Just as Inuits have absurdly precise words to describe snow on account of it being such an integral part of their quotidian experience, Thais have their ghost terms.

Just as Inuits have absurdly precise words to describe snow on account of it being such an integral part of their quotidian experience, Thais have their ghost terms.

Many ghosts are geographically bound to their place of death. Thailand’s ubiquitous spirit houses, built outside every home and office in the country, are made to accommodate ancestors and ghosts tied to the land – seen as the real landowners. No Thai, young or old, will walk past their spirit house without at least a wai (a show of obeisance characterized by pressed palms and a bow), but they often leave offerings of flowers, figurines, and food or red Fanta (to represent blood). If expansions are made to the home, often they will be made to the spirit houses as well. A farang friend opened an office here last year and within a week, his staff were on strike because he hadn’t invited a monk to seek blessings from the spirit house yet. While ghosts residing in spirit houses are relatively benevolent if you appease them properly, others are less predictable. Just last month, restaurant waitstaff kindly advised me to avoid their second-floor bathroom because it had a ghost in it that occasionally frightened the guests. An electrician who unfortunately died while doing the wiring at my previous office was frequently sighted by staff and blamed regularly for infrastructure malfunctions.

For the more “free spirits,” those able to wander the earth and strike at whim, Thais have methods of personal protection that date back millennia. Sak yant tattoos, made wildly popular in the West by Angelina Jolie and Cara Delevingne, may only be administered by trained monks, who chant as they hammer in the ink with sharp metal or bamboo rods. They are said to give the bearer good fortune, power, and defense against evil spirits, by invoking good spirits. During the annual sak yant festival, important for recharging tattoos, many bearers become possessed by their tattoo spirits. Amulets are also standard amongst Thais. The most widely worn one is of a meditating Buddha, designed and originally blessed by the monk Somdet Toh, famous for many deeds including trapping the spirit of Mae Nak in the bone of her forehead.

Somdet Toh amulet

Where does this deep-rooted ghost culture stem from? It certainly has historical echoes from the tradition of animism that predates Buddhism in the region. The reason the tradition has survived over 2,000 years is due to its compatibility with the Buddhist concept of karma. (Or, conversely, perhaps the reason Buddhism took root in Thailand was because karma was compatible with animistic beliefs.) Souls carry weight from their previous lives, and sometimes this stops them from reincarnating immediately, or ever. Importantly, the Thai Theravada Buddhist culture encourages making merit in this life to benefit the next life. However, observances involving spirits directly impact your current life; ghosts do not follow you into the next. Thus, practicing both religion and superstition is a very practical way to secure your long-term and short-term future.

This easy compatibility, as well as the prevalence of ghosts in popular contemporary Thai media means that ghosts are here to stay. Thailand’s highest-grossing movie of all time, Pee Mak (2013), is a retelling of Mae Nak’s story. Commercials and TV shows often feature ghosts. Popular radio show The Shock has been running for three decades, where locals call in from midnight to 3 am to share their supernatural encounters with listeners. The host, celebrity ghost hunter Kapon Tongplub, also sends staff to haunted houses to call in with live investigations, many of which involve the use of ghost radars and other technology.

It’s not just the ghost detection methods that have been updated over time. The ghosts themselves have become more metropolitan. Basket-weaving spirits are fading into irrelevance, but cyber spirits or air-conditioning spirits are taking their place. Judging by offerings left by believers, they now prefer Coca-Cola or Sprite to tea or juice. They live a little more luxuriously, too. For example, the company Holy Plus sells cutting-edge spirit houses made of glass and chrome, with electrical wiring and lighting – modern-day homes for the modern-day ghost. Ghosts here aren’t going away anytime soon; instead, they’re evolving with us.