Malaysia’s Democratic Moment

By Shaun Tan

Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and Staff Writer

2/5/2019

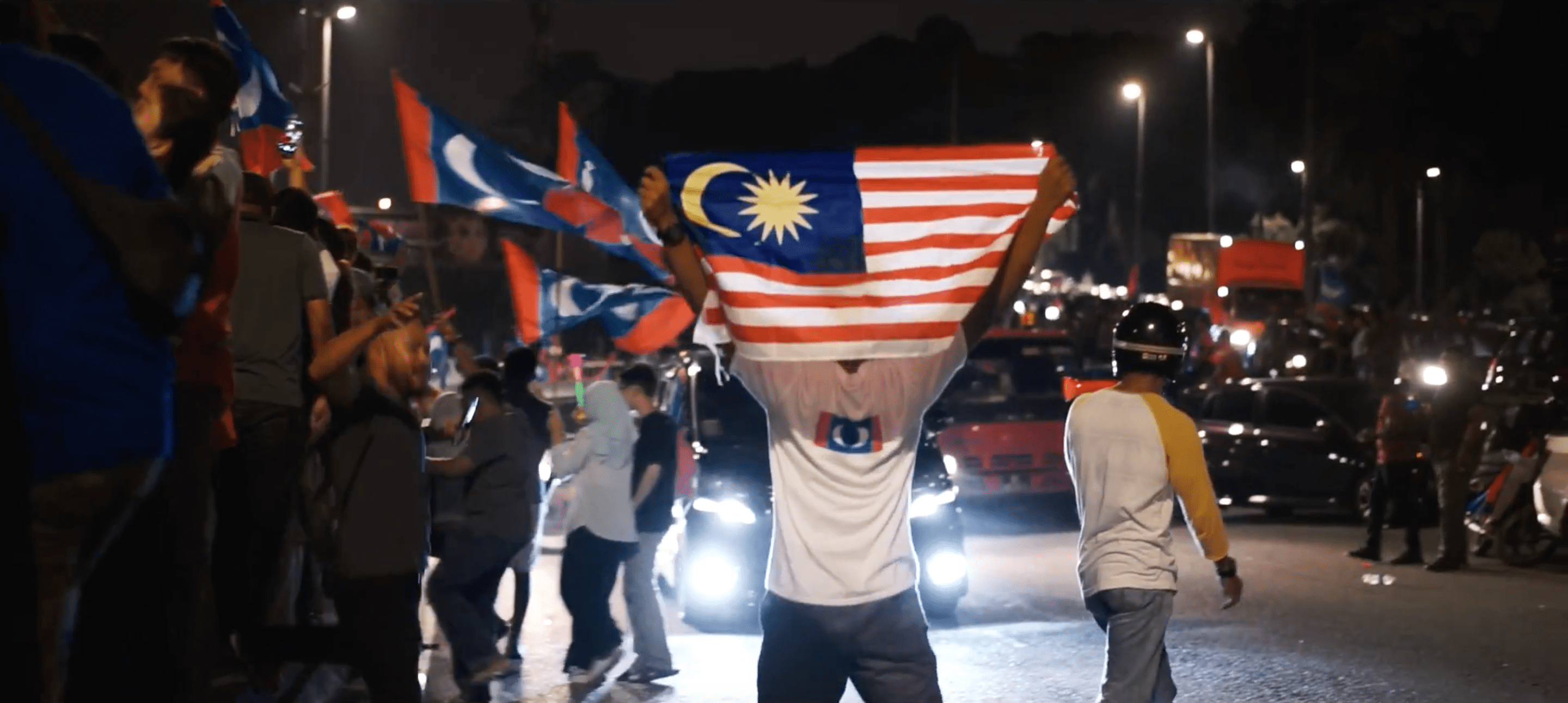

Pakatan Harapan supporters celebrate the May 9th election results

9th May, 2018

Victory! It blared from the horns of thousands of cars, burst across the night sky in showers of sparks, swelled in the hearts of millions of Malaysians, on the streets and public squares where they cheered and waved flags, in restaurants and living rooms across the country, and beyond that, in the hearts of the Malaysian diaspora around the world who sat rapt before computer screens, who sobbed into phones, barely able to comprehend a victory that was as momentous as it was unexpected.

The fall of the Barisan Nasional party that had ruled Malaysia since independence – a party that had grown increasingly despotic, corrupt, and Islamist – Malaysia’s rebirth, its redemption, its democratic restoration, for surely we had a republic now, if we could keep it. We all knew we were witnessing history in the making, and there would be calls later for this victory, or at least the 1MDB corruption scandal that helped bring it about, to be included in the national history syllabus, and even the most cynical amongst us suspended our doubts – about the shakiness of the coalition that had won power, the record of our new-old prime minister and the sketchiness of his succession plan – came to speak without irony of a New Malaysia and all it portended. It couldn’t last.

***

It didn’t.

A year on and much of that hope has given way to disappointment and disillusion, and the new government helmed by the Pakatan Harapan coalition manages to look both increasingly authoritarian and increasingly feeble.

The Pakatan Harapan coalition manages to look both increasingly authoritarian and increasingly feeble.

When campaigning, Pakatan politicians railed against the autocracy and religious intolerance of its competitors, the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) party, and the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS). In its manifesto, it vowed to repeal a raft of repressive laws, including the Printing Presses and Publications Act, which was used to control the media, the Prevention of Crime Act, which allows detention without trial for up to 60 days, the National Security Council Act, which allows for the designation of “security areas” in which deadly force can be used with impunity, and the Sedition Act, which allows the imprisonment of anyone deemed to have incited “hatred” or “discontent.”

Yet all those laws remain on the books. If the mantle of power has persuaded Pakatan’s leaders of the utility of such legislation, it was a swift conversion. One might have expected Malaysia’s prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad – who, after all, led BN and ruled as a dictator from 1981-2003 – to harbor such sympathies; one expected better, however, from people like Deputy Prime Minister Wan Azizah, Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng, Minister of Defense Mohamad Sabu, Minister of Communications and Multimedia Gobind Singh, all of whom have been persecuted under such laws themselves, or seen them used against friends and family, and whom democrats hoped would check Mahathir’s authoritarian instincts.

Worse still, Pakatan even seems to be seeking to expand the number of draconian laws. It is putting together a religious and racial hatred bill, a repressive hate speech law that would impose a jail sentence of up to seven years on anyone who “insults a religion or race.” An egregious enough encroachment on free expression in any society, such a law is infinitely more harmful in a society like Malaysia’s, where even questioning affirmative action policies, discussing whether people should be allowed to convert out of Islam, or even a non-Muslim uttering the word “Allah,” have been deemed “insults” to religion or race; such a law will quickly be abused to shut down legitimate inquiry, criticism, and debate. No less a supposed moderate than Lim Guan Eng has called for harsher punishments against those who insult a religion, and the government has set up a special unit to monitor insults to Islam. Not that new laws seem necessary even for that end – under existing laws people are being arrested and charged for such alleged insults.

Pakatan even seems to be seeking to expand the number of draconian laws.

During his long political career, Mahathir has been called many things – Machiavellian, tyrannical, steely, stubborn, unapologetic. This was the man who, for more than 20 years ruled Malaysia with an iron fist, who neutered the judiciary when it refused to bend to his will, who imprisoned scores of his political opponents on dubious pretexts, who, to this day, refuses to apologize to Anwar Ibrahim – the man he has promised to cede power to – for jailing him for five years under trumped-up sodomy charges back in 1999. (It’s a mark of how low the bar in Malaysian politics is that Mahathir is still better than Najib Razak, the man he unseated.)

Mahathir Mohamad at 93: still anti-Semitic, still unrepentant about jailing Anwar, still seemingly fond of draconian laws, and still the least bad option at present

One thing Mahathir has never been called, though, is weak, which makes Pakatan’s recent policy capitulations surprising as well as disappointing. Over the past year, Pakatan tried to push forward two initiatives, first, the recognition of the standardized examination certificate for local Chinese language schools for university entry, and the second, the ratification of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Both were good initiatives that would have reduced discrimination and leveled the playing field. Both were abandoned by the government after protests by racial supremacists from the majority Malay ethnic group who feared the removal of discriminatory barriers would allow minorities to outcompete them, and who wanted to continue to benefit from Malaysia’s system of institutionalized racism.

Pakatan is appeasing Islamic extremists because its competitors, BN and PAS, have bound themselves closely to them and are seeking to win the Muslim vote by branding Pakatan “anti-Islam.” But this appeasement of Islamists is likely to work the way appeasement usually does – it will only embolden them, cede them the initiative, whet their appetite, and show them their bad behavior is rewarded, prompting ever more ridiculous demands.

In place of a mixture of authoritarianism and weakness, Pakatan should adopt a policy of liberty combined with strength. It should respect and protect the fundamental freedoms outlined in Malaysia’s Constitution as well as innumerable international human rights documents (many of which Malaysia has signed), including freedom of expression and freedom from discrimination, freedoms that are essential to any thriving democracy. At the same time, when it comes to those who would react to the peaceful exercise of those freedoms with violence, or the incitement of imminent violence, Mahathir should respond with the steel for which he is known. In defending liberty against the assassin’s veto, he should be steely, stubborn, utterly unapologetic. A few sharp examples should teach people like that the importance of self-control. Nor would he have to resort to draconian laws to do this: Malaysia’s conventional criminal laws, the kind found in any liberal democracy, are more than adequate.

Of course, no one can expect Pakatan (or most political parties) to care more about democracy than winning the next election. Pakatan is now leaning towards the right because it wants to court the Islamist and the conservative Muslim vote and because it has taken the liberal and the moderate vote for granted. It thinks the liberals and the moderates (who make up its base) have no choice but to vote for it, because the alternatives, BN and PAS, are so much more unpalatable to them. The liberals and moderates must show Pakatan that they always have a choice. Pakatan might not lose the next election because liberal and moderate voters switched their votes to BN or PAS. It could lose because they supported and voted for Pakatan in the end, but did so reluctantly: they didn’t volunteer to help out during the campaign period, they didn’t post all about it on social media, they didn’t round up five of their friends and family members to go to the polling centers on election day. These things matter, and by such things are elections often won or lost.

The liberals and moderates must show Pakatan that they always have a choice.

Pakatan could also lose because liberal and moderate voters were so disgusted they didn’t vote at all, because they decided to play the long game – to risk having BN return to power so that the next time Pakatan wins it’ll take the concerns of its base seriously – because they don’t see the point in having a two-party system if both parties are almost equally despotic and Islamist. Ultimately, it’s up to them, not Mahathir or Anwar or any other Pakatan leader, to keep Malaysia democratic. To do so, they have to be prepared to criticize and to demonstrate when the government backtracks on important promises, or fails to defend fundamental rights, and to remind Pakatan that they are the reason it holds power today, and that they can determine if it keeps it.

***

Writing history is a tricky thing, particularly when not enough time has passed to know the significance of events.

Police raid an apartment linked to former Prime Minister Najib Razak, seizing suitcases of cash and valuables suspected to have been obtained illicitly

Sure, we could include the 1MDB corruption scandal and the Pakatan victory in the history syllabus, but their significance depends on whether that’s followed by an “and” or a “but then.”

For example, “the 1MDB corruption scandal helped bring about the fall of the authoritarian BN party, a change of government, and the restoration of democracy to Malaysia” – there it would certainly be significant.

What if instead, however, it was “the 1MDB corruption scandal helped bring about the fall of the authoritarian BN party and a change of government, but then BN regained power in the next election and went back to robbing the country for the next 50 years?” Or “the 1MDB corruption scandal helped bring about the fall of the authoritarian BN party and a change of government, but then the new government became near as oppressive as the one it replaced?”

See? It’s all a matter of perspective.

To be fair, Pakatan seems better disposed towards democracy than its predecessor. It abolished the National Civics Bureau, whose chief function seemed to be to indoctrinate people with racist and extremist propaganda. It amended the Universities and University Colleges Act, allowing students to engage in political activities on campus. It repealed the Anti-Fake News Act, which the BN regime enacted to muzzle the media. When the police arrested someone for insulting Mahathir on Facebook, he rebuked them for doing so – something his predecessor (or perhaps even Mahathir himself circa 2003) would never have done.

Pakatan still has time to fulfill its promises, its supporters still have time to make sure it does, and the history of the 1MDB saga, and that most extraordinary of elections, is not written yet.