Ordinarily Extraordinary

By Lisa Yin Zhang

Staff Writer

2/4/2020

Isamu Noguchi. Leonie Gilmour (Mother). Terra-cotta. c. 1932. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society.

You could say Isamu Noguchi, the great Modernist sculptor, led a charmed life. The son of a renowned Japanese poet — the first to ever publish in English — his birth was celebrated in newspapers from the California Sunset to the London Nation to the Tokyo Yorozu chōhō. Back in the States, alone, at 14, he found refuge in the enduring kindness of strangers, who housed him, fed him, educated him, and paid his college tuition. At 18, a nonplussed Noguchi so impressed the director of a New York art school that he was offered not only a fee remission but a paid position on the spot. At 21, on the prestigious Guggenheim fellowship, he walked into a café in Paris, announced his desire to meet the sculptor Constantin Brâncusi, and found himself apprenticed to the famously selective artist the following day. From there he tore through the international art scene, drinking with Alexander Calder in Paris, designing stage sets for Martha Graham in New York, flying around the world to make sculpture gardens in Jerusalem, bridges in Hiroshima, murals in Mexico City. There was a brief, scintillating marriage to Yoshiko (Shirley) Yamaguchi, Japan’s foremost movie star, complete with televised wedding, and flings with women from the painter Frida Kahlo to the dancer Ruth Page. In the final years of his life, Noguchi would represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, cementing his place in the international artistic pantheon.

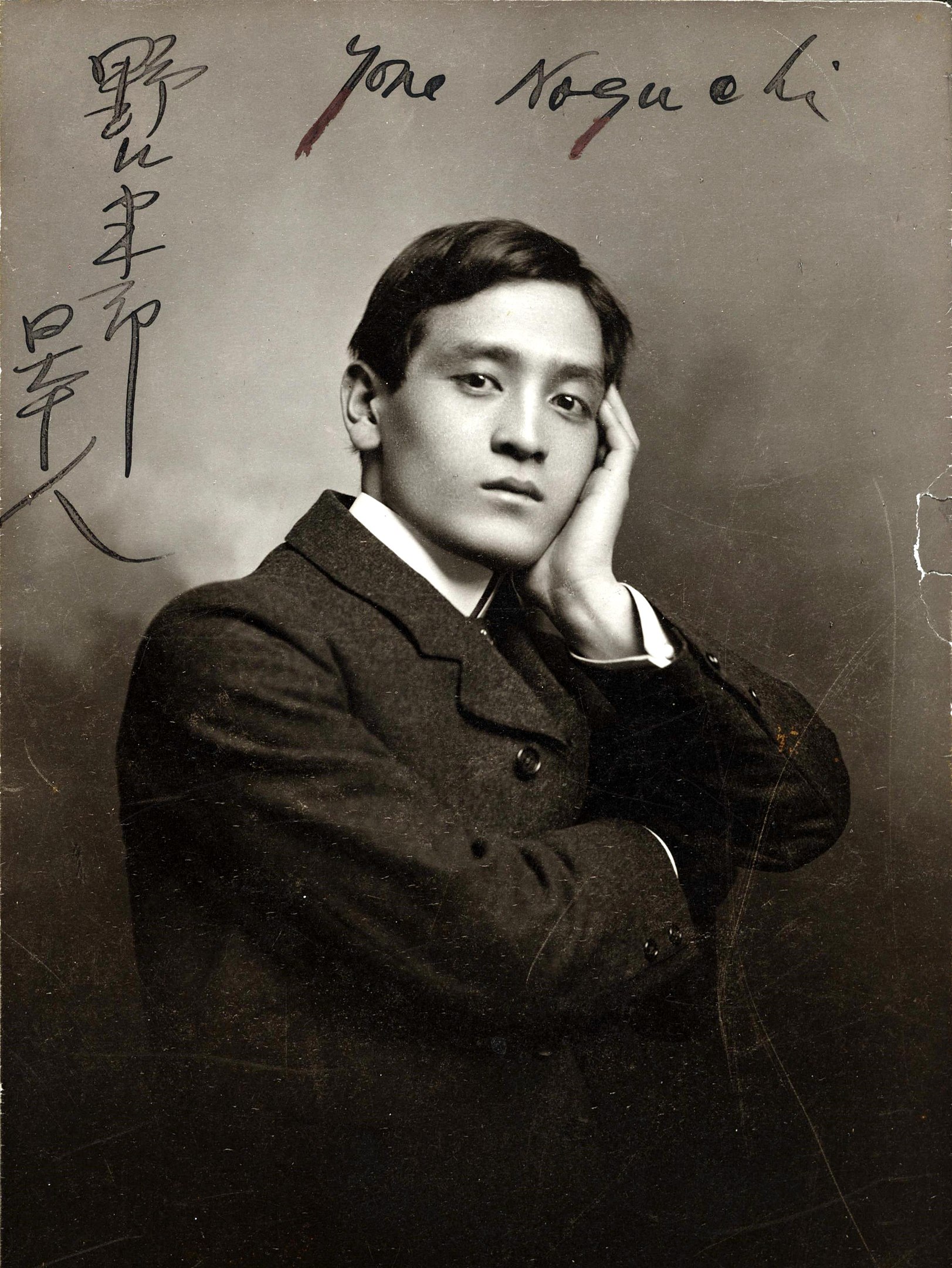

Before he settled into a more modest age, a young Isamu Noguchi often told a Christ-like tale of his own genius. “Give me uninterupted [sic] time,” he wrote to Edward Rumely, one of his mentors, at 23, “and I will rival the immortals.” If there was an artistic wellspring, it was his father, the famous poet Yonejiro Noguchi, who introduced the haiku form and Noh drama to the west, under whose influence he bristled, was overshadowed by, then ultimately overcame. In his application for the Guggenheim fellowship, he wrote: “My father, Yone Noguchi, is Japanese and has long been known as an interpreter of East and West, through poetry. I wish to fulfill my heritage.” With that desire to fill a new role, to become a new person — an artist — he decided to change his last name to his father’s. “[It] somehow [seemed] more appropriate than my mother’s name, Gilmour, which I had used till then,” he said. “I felt like Jesus Christ.” A trajectory of genius, from Father to Son: a story without mothers.

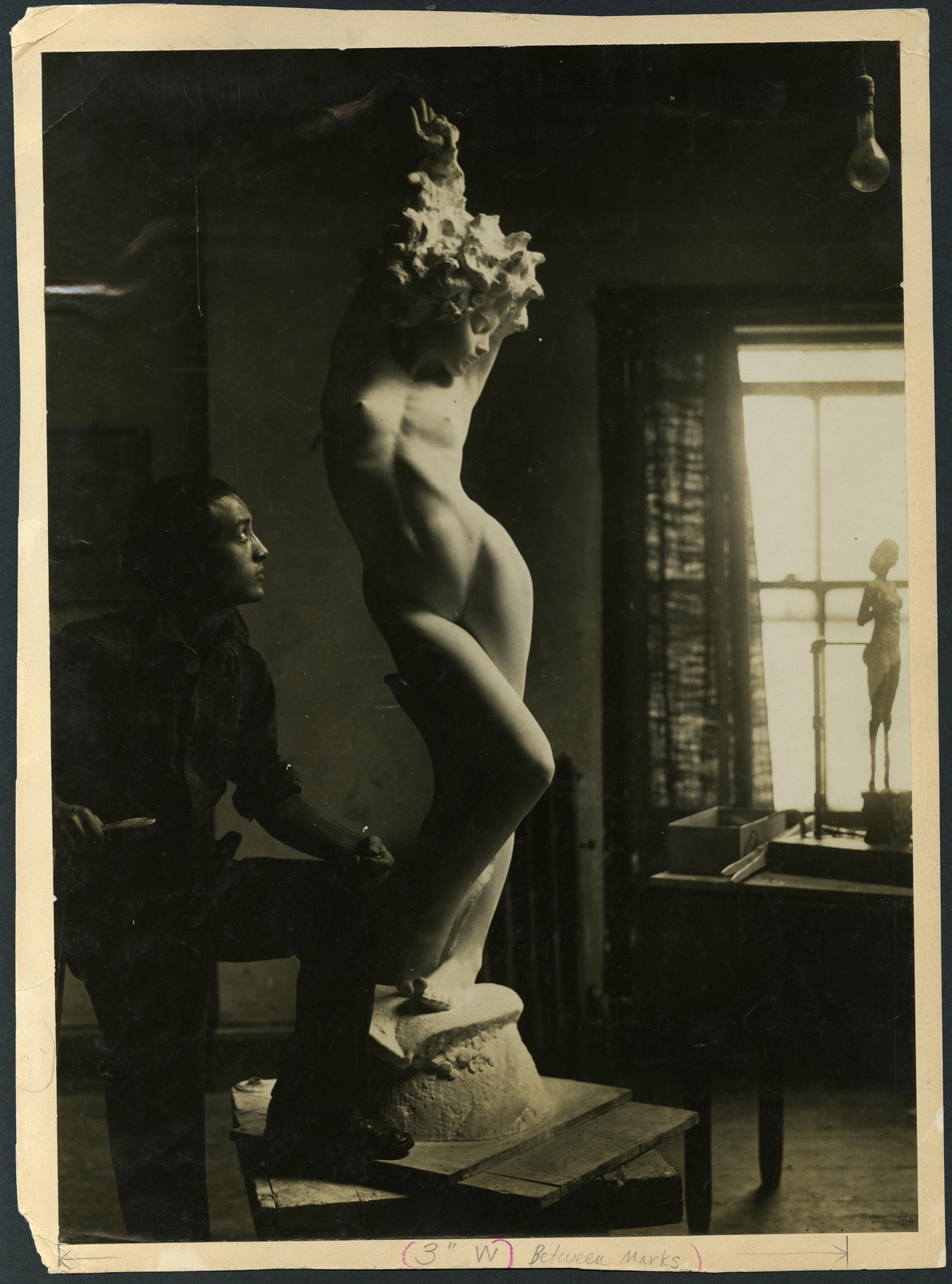

Isamu Noguchi with his sculpture, Undine (Nadja),1926. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society.

Of course, no artist comes from a void, and especially not this one, who was the son not of a poet but of two. Though the subject of a semi-fictionalized biopic as well as a biography, the story of Léonie Gilmour, writer, poet, mother, is largely lacunae, often eclipsed by her more-famous relatives: Yone, her partner, the poet; Isamu, her son, the artist; Ailes, her daughter, the dancer. She crossed paths with many luminaries — Marie Stopes, a paleontologist and campaigner for woman’s rights (and eugenicist), Charles Warren Stoddard, a scholar and professor, Lafcadio Hearn, an acclaimed writer of Japanese ghost stories — and was overshadowed by them at the same time that she’s now remembered largely through their recollections. This pattern of shadow — letters lost, stories unwritten, things forgotten — and light — the glow of others, the published work, the possessions left behind — defines Léonie’s legacy. She led a life engulfed by large arcs of history: born into a recession, marrying during the precise six-year window that rendered it illegitimate, run out of California with her mixed-race child as anti-Japanese sentiment grew febrile. At the same time, she comes to us with an intimate lucidity, slivering in and out of others’ lives, divulging little hints of her own. We know how she joked: padding around their humble apartment, she and her roommate would blurt the last line of her short story (unpublished) whenever something broke (often), giggling: “The opal seems to have exploded!” We know that she was gentle and quiet, that the pen was her preferred form of association. That she was an aesthete: “I confess the sort of poetry I like best is that which makes me slightly drunk,” she wrote once. That she was dreamy: “And I find ideas to be not a necessary ingredient in producing the divine intoxication, in fact they have a sobering effect.” We know that in anger, she resorted to a punitive coldness, rather than an emotional outburst; we know that she baked good bread. That she was an artist and scholar in her own right, delivering lectures on Japanese prints at the Brooklyn Museum, crafting jewelry, sewing clothing, stringing for the New York Times, and writing often, but not prolifically. Partly by circumstance, partly by design, Léonie Gilmour used her typewriter mostly for other people’s ideas.

Léonie Gilmour used her typewriter mostly for other people’s ideas.

When Isamu was only a baby, C. W. Stoddard, a famed author, editor, and scholar of Polynesian culture, wrote to Léonie: “I hope you are keeping one of those kid chronicles in which all the quaint and clever things he says or does are recorded.” Convinced already, somehow, of Isamu’s brilliance, and insistent that Léonie take the role of documentarian of that brilliance, he added: “This Baby Boy is to be like no other Baby Boy in all the world.” Léonie dismissed the idea. “I never liked chronicles,” she said. “The things worth keeping seemed not to be in them[:] the bright winged moment…the deeps of the heart.” The same creed seemed to apply to her own life, which was archivally fragmented, flickering, fleeting. When she finally set out to write Stoddard’s “kid chronicle” decades after the fact, caving to the adult Isamu’s beseeching, she cheekily titled it “The Kid Chronicle That Was Not Written,” then gave up the idea entirely. “Time is something I do not understand,” she wrote. “Forward and backward is all the same. The yesterdays play at hide and seek with today and all the tomorrows.” Late in life, Isamu would arrive at the same idea himself, un-indebted or unbeknownst. “We are no longer so sure that time flows in one direction only,” he wrote, “at least not in art.” In reflection, he added, “I myself seem to go in a circle — a spiral, I hope, moving a bit laterally as well.” Indeed, as time unraveled, Isamu would seem more and more his mother’s son. “I am the son,” he said ultimately, “of my mother’s imagination.”

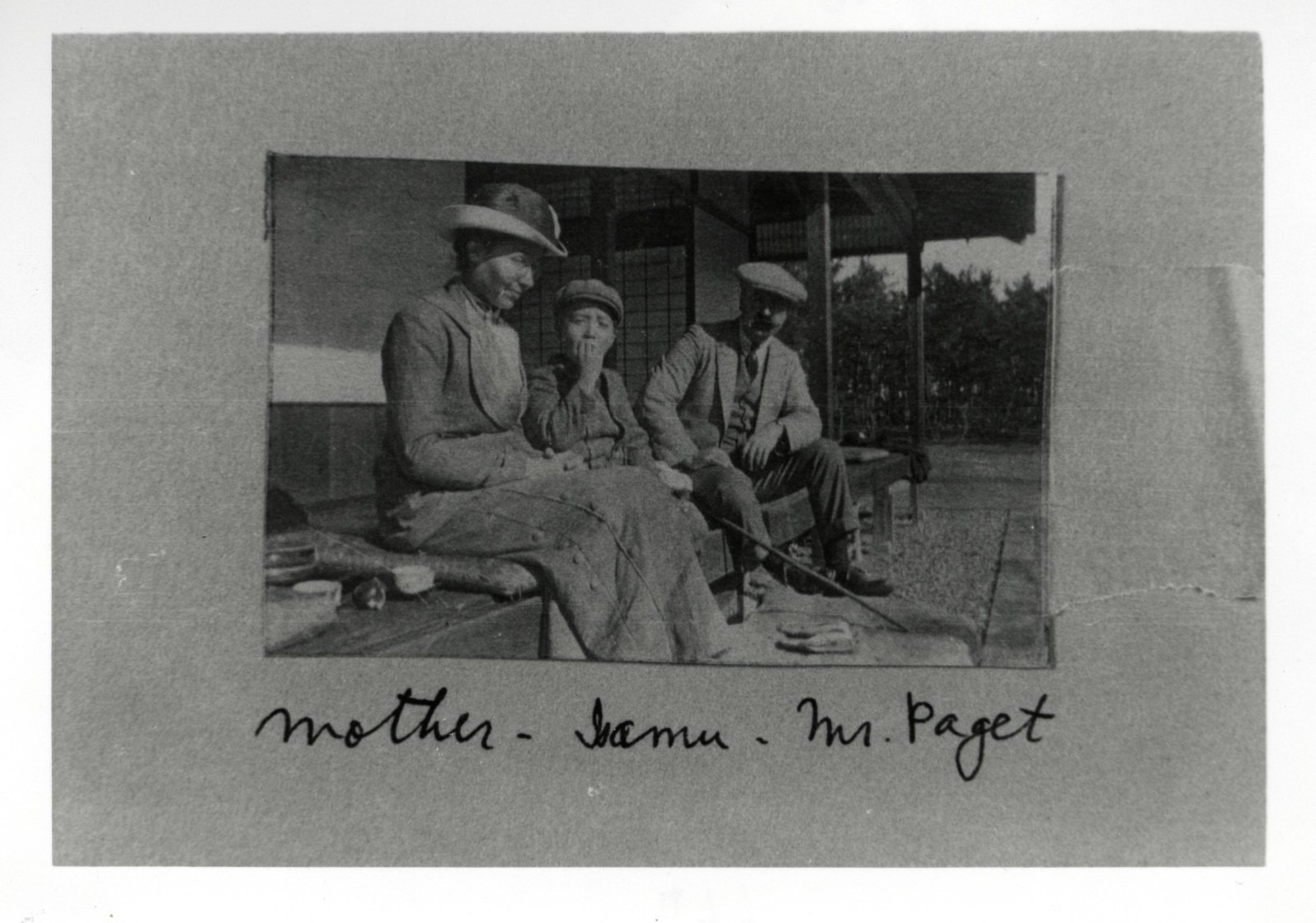

Isamu Noguchi as a child in Japan, with his mother Leonie Gilmour and Paget, a friend. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society.

Léonie Gilmour was born into poverty on June 17, 1873 in New York City. A friend of Léonie’s would later remember Andrew, her father, an Irish immigrant often unemployed, as a conspiracy theorist and anarchist who spewed theosophic, Masonic, and Vedantic philosophy, and plotted bombings at the same time that he doted on his daughter. Her mother, Albiania, was a quiet, regal woman, daughter of the owner of the Brooklyn Daily Times, who was contemptuous of her husband and went to work in his place when he lost his job. Léonie would later write, in “St Brigitta’s Place,” a fictionalized and unpublished account of her own life: “It is a story of poverty and heroism, those grim fairies who presided at my birth, to whom I owe whatever fibre of strength is in my being.” Yet she was always a romantic. In the same undated story, she wrote: “yet I love, Oh I love — the velvet-footed romance who steals past me unawares, leaving but a breath, a warmth, a light, the echo of heavenly laughter, to make me dream in happy indolence, forgetting the Poverty.”

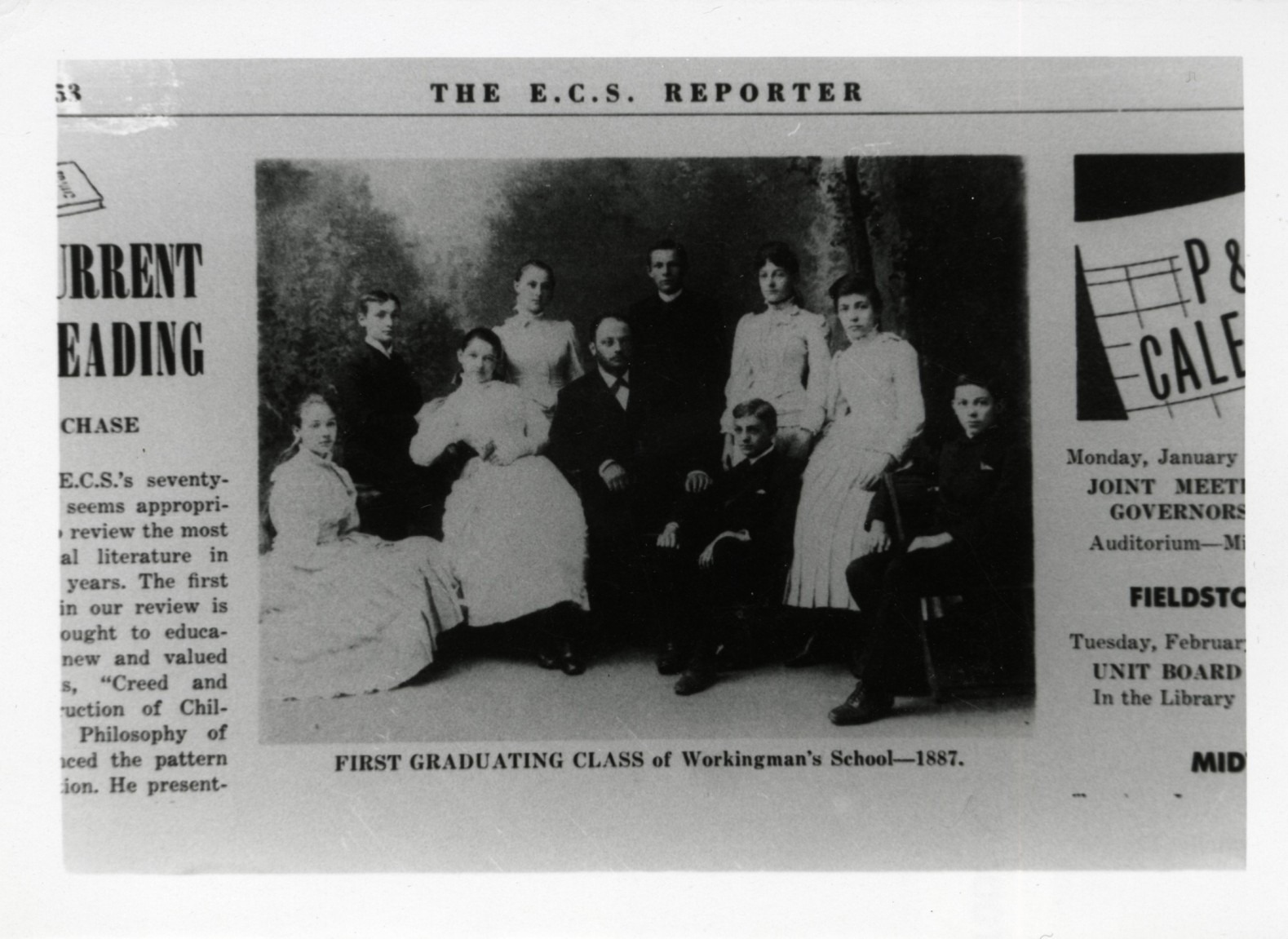

Léonie attended The Workingman’s School, a newly-opened progressive school intended for the children of working people. It espoused handicraft, teaching that one learned the properties of things only by toiling over them, and emphasized modeling in clay and sketching. She would later follow the same methods in raising her own children, recruiting Isamu to help build their house at the age of 10, and holding off teaching him to read for years, apparently to preserve his eyesight. “She would not allow him to slip into the dreamy indolence of poetry, the world of his father’s books,” wrote Edward Marx, a biographer of Léonie. “He must remain active.” She nursed dreams of sculpting an artist out of her son: he was only 14 months old when Léonie wrote to Yone: “I would like to put him to an Art school somewhere, where he will have eye and hand trained to express his idea.” He was, or became, skillful with his hands, sculpting a clay wave with a blue glaze that impressed his primary school classmates, before embarking on a career as a renowned sculptor. (He did, however, remain forever a terrible speller — even by the end of his life he never figured out how to spell the word “dilemma.”)

As Léonie’s graduation date neared, an opportunity opened up: a scholarship at the newly-formed Bryn Mawr private school. The Workingman’s School could nominate one student. Léonie was put up for it, admitted, and then excelled. A few years later, she applied for the single four-year full scholarship offered at Bryn Mawr College. Its entrance exam was said to be one of the toughest at the time — harder even than Harvard’s — testing algebra, geometry, science, and history, on top of an incredibly long reading list. She passed.

Leonie Gilmour (far left) in the first graduating class of the Workingman’s School, 1887. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society.

At Bryn Mawr, Léonie would receive one of the best educations available to an American woman at the time. Though one of the poorest students in her class, like her own fictional Brigitta, she felt no shame, believing that poverty was not shameful but ennobling, and valuing her own individuality above all else. She would major first in Chemistry, but, as recollected Marie Stopes, “found chemistry so easy that it was no mental discipline, so she took history, where dates have no reasons and are therefore hard to remember.” She met Catharine Bunnell, a wealthy Connecticut woman who would become roommate, pen pal, and good friend. (In letters, Léonie would forever spell “Catherine” with an “e” for no reason other than that she liked it better, and would sign off: “Love, Brigitta.”) In her final year at Bryn Mawr, Léonie turned her sights abroad. But Paris, a mere vacation spot for her wealthy classmates, would likely mean draining the rest of her scholarship and leaving Bryn Mawr sans diploma. It would be unpragmatic, impulsive, even foolish, to go. At the same time, the prospect was exciting, and it moved her. Tellingly, Léonie chose Paris.

It would be unpragmatic, impulsive, even foolish, to go. At the same time, the prospect was exciting, and it moved her.

Her own yet unborn son would eventually marvel at the spiraling nature of time, the way events seemed to echo both past and future. A quarter of a century after Léonie set sail, Isamu would set for Paris, equally broke. The two of them would never stop moving, criss-crossing continuously across the globe. In college, Léonie wrote, in an essay on Victorian author George Meredith, on the vulnerability of women in the hands of fickle and flighty men. “Conventions protect the weak,” she observed. “Let it be remembered, woman and child are both utterly dependent upon the caprice of man; and the Mighty Convention of Marriage.” Leaving Bryn Mawr and working as a copyeditor in New York, she answered an advertisement in the New York Herald: “WANTED — A lady teacher to give instructions in English, writing and composition.” Thus entered Yonejiro Noguchi. What followed was a volatile tale of marriage, illegitimate, half-hearted, then annulled; Léonie would have to depend on herself.

Yonejiro Noguchi

Yone was already a writer of some note, having established himself in San Francisco. But what started out as a copyediting job quickly ratcheted up into Léonie seemingly doing Yone’s work for him. “Here are the next three chapters,” Yone wrote to her, around the same time that he began addressing her as “Léonie” and not “Miss Gilmour.” “Say, listen, can’t you fix them according to your own idea?…Anyhow I wish you will arrange them to your idea.” He was wheedling, needy (“Is the story ready?”) and the quality of his English seemed to fluctuate with the amount of work needed to fix his drafts (“This broken English is not refined so well, so you might change as much as please. O please, do it!”) as well as the amount of personal responsibility he was willing to take. Apologizing for having denigrated one of Léonie’s short stories for including a female character who had the gall to get remarried, Yone wrote: “Now you will see that a brown Jap cannot be equipped with the very quality to be a gentleman.” Explaining himself further, he added: “I firmly believe that any woman or man can’t allowed to be so indulging in matrimony…Many weak people often do it, but I despise them…I will never put such a character in my story.” Ironically, he would become that very character in hers.

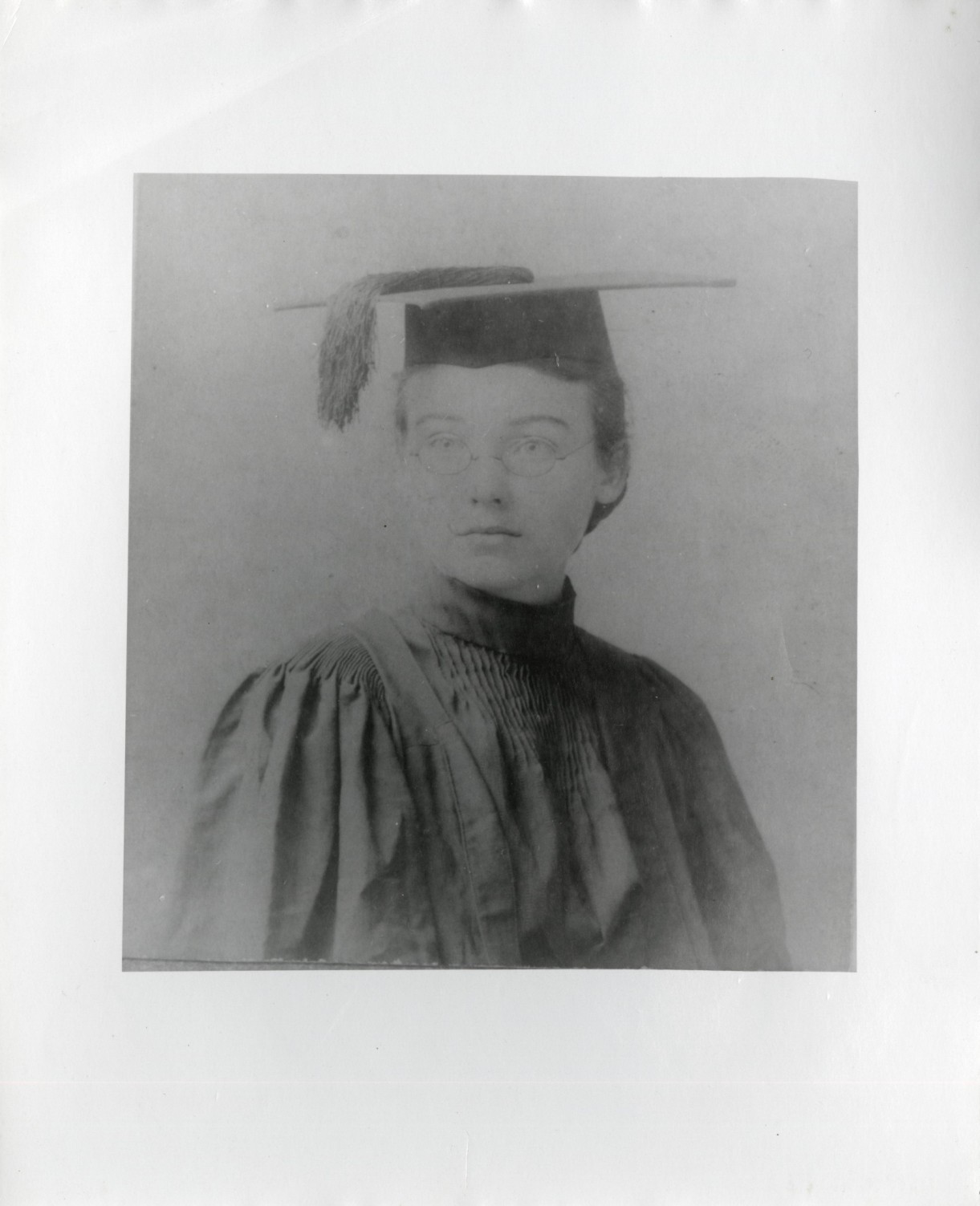

Portrait of Leonie Gilmour, 1904. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society.

It’s unknown when exactly their relationship transitioned from professional to romantic. What we do know is that they began officially dating in 1903, and, at the end of that year, Yone scrawled, on a sheet of loose leaf paper, a marriage declaration of dubious legal validity: “I declare that Leonie Gilmour is my lawful wife. Yone Noguchi. 18th November, 1903.” The following February, Léonie felt, “almost as soon as it happened,” that she had conceived. Yone laughed it off. In November, Isamu was born. But Yone was already gone. He had fallen in love with Ethel Armes, a vivacious young journalist. He wrote passionate homages to their love, and proposed to her. He departed for Tokyo.

Léonie met this turn with the steady, clear-eyed gentleness, touched with a hint of wistfulness, that was her nature. “I have a fancy, as if he were a bird that flew through my room and is vanished,” she wrote Catharine. “And I console myself — try to — that I am more fortunate than other women who must see their lovers grow old, indifferent, perhaps commonplace, whereas mine will be ever young, and ever poet.” Joining her mother in Los Angeles, she gave birth alone, except for a reporter from the Los Angeles Herald who had forced her way into the room. Léonie begged the reporter not to write the story; the reporter promised, and wrote it anyway. (Years later, en route to a quiet study trip in Japan, where his estranged father told him not to return and certainly not bearing the Noguchi name, Isamu would make the same mistake. He confided to a stranger who turned out to be a reporter, and docked in Tokyo to enormous fanfare and a forced reconciliation.)

Ethel Armes, Yone’s new bride-to-be, saw the Herald article and sent a friend, Elizabeth Converse, to investigate. Elizabeth confirmed the reports, and wrote back, of Léonie: “In appearance Middle-West as they hang over the back fence. In manner as English [as] a queen.” Léonie, it seems, was smitten with the baby Isamu, who had sparkling eyes and a sunny disposition. “She is peace and happiness and courage and hope,” she continued. “If she were the Mother of Jesus, she could not be more sure of herself or happier.” Elizabeth was entirely charmed by Léonie, too. Having witnessed Ethel’s agony up close and Yone’s misery secondhand, she had “expected to find a third dose” in Léonie. Instead, she wrote, “Her attitude has simply swamped me…Oh! I can’t understand it. She does not want help, or money, or anything; just her baby.” She concluded, most simply and most devastatingly of all: “You would like her.”

Isamu Noguchi as a child in Japan, with his mother Leonie Gilmour and her pupils, November 1910. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society.

It seemed everybody did. Of his own father, Isamu would say: “I did not think he treated her fairly.” When Isamu returned to Japan to pursue his studies, Yone’s brother, Totaro Takagi, let him stay in a new house he had built. Takagi “showered me with kindness,” wrote Isamu, “as did other relatives who gave me to understand they favored my mother.” After Yone wrote a derogatory article toward Americans, the Japan Times ran a savage hit piece with the title: “American Men Mere Rustics — Women Sentimental, Says Poet: Yone Noguchi flays the country which helped him get his start as ‘undeveloped’ and ‘woman-ridden.’” In the body of the article, the Japan Times clearly expressed pity for Léonie’s plight, who had by that point moved to Tokyo at Yone’s behest to find — already partially resigned to the probability — that despite promises of rekindling their relationship, he had already remarried to a Japanese woman. “The author was the recipient of many kindnesses in America,” wrote the Japan Times, “where he married an American girl whom he brought to live in Japan. His moral conduct and treatment of his wife led to a separation.”

But Léonie, true to her independence and sense of pride, was not happy to play the part of victim. She penned a sharp rebuttal. “Though I was not happy as Mr Noguchi’s wife,” she wrote candidly, “I did not consider myself to be ill-used. On the contrary, he used such courtesy to me as I should expect from one of my own countrymen.” In response to the claim that she was now forced to teach in order to support herself, Léonie bristled at the implication that Yone should be expected to support her in the first place. “That I am making my living by teaching is hardly a matter of commiseration,” she wrote. “Teaching was my chosen profession for many years before I met Mr Noguchi.” Indeed, Léonie was serene and gently playful — but was caustic and biting on subjects that incensed her sense of justice. When an editor at Liberty magazine suggested that Léonie write on the subject of interracial marriage, her first attempt was a series of light-hearted vignettes, which was rejected as lacking in conclusions. In response, Léonie launched into what I think to be the most scathing and well-articulated essay of her extant literary career.

Léonie was not happy to play the part of victim.

Léonie laid into the editor for suggesting that there existed something of an American and Japanese “type.” “The literary ‘type,’” she wrote, “is largely a vogue…depending largely on the brilliancy, or popularity, of his originator.” Whatever Japanese type existed was caricatured, incomplete, and wholly inaccurate, she argued, because so few had taken pains to study Japanese culture through the medium of their own language and literature. Decades before Edward Said’s Orientalism distilled those ideas and threw it back at the culture with force, Léonie was excoriating the widely-held view of the East as static and the West as dynamic as a worldview that served and perpetuated the aims of the latter. She wrote: “‘The fundamental differences between the East and the West’ is one of those stock phrases that, once accepted and adjusted to one’s vision like a pair of imperfect magnifying glasses, discover, exaggerate, and distort all the minutest differences on which they are focused.” Moreover, she paraphrased the British writer Norman Douglas to attack the supposition that dynamism — and with it, “progress” and capitalism — was in the first place fundamentally good. In dynamic societies, wrote Léonie, we find progress, but not civilization: “Progress is a centripetal movement, obliterating man in the mess. Civilization is centrifugal: it permits, it postulates…Progress subordinates. Civilization coordinates.” The editor of Liberty might have expected Léonie, a presumably bitter white woman, divorced from an unfaithful and unreliable Japanese man, to write an easily-consumed, reader-placating piece against interracial marriage at a time when public sentiment toward mixed-race couples was at its nadir. Léonie instead penned a screed that undermined not only the idea of the degeneracy of interracial marriage but also the society that gave rise to it and even the readership who would believe it. “All such generalization, containing a modicum of truth, becomes false when turned to universal application,” she concluded presciently. “The truth of today is the falsehood of tomorrow.”

Léonie was perhaps at her most brilliant in these fiery newspaper editorials — but we will never know for sure. As she also quoted in the essay to Liberty: “To appreciate things of beauty…a man requires intelligence. To create them…he requires intelligence and something else as well: time.” Alas, time was the very thing that Léonie always seemed short on, as she moved onto the next phase of her life, managing an import-export business, delivering lectures, always, it seems, en route to the next place: New York, Connecticut, Maine. Of what she could manage to write, between 1918 and 1926, her letters to Catharine, her most faithful correspondent, are lost. Some letters to Isamu remain from that time; from that, we glean that she had begun to write more seriously. But little survives.

Portrait of Leonie Gilmour. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society.

But also hidden in the unpublished manuscript to Liberty was a kind of credo. A marriage’s dissolution, said Léonie, was not a sign of its failure. Marriage, like a tree, could be judged not by its own growth but by its fruit. So might a life. Her own work was diffuse, ephemeral, written in sand, not stone: moments of pleasure, unrecorded; relationships built, and crumbled; and finally, the work of her children, who thrived, and left her behind. In a so-called dynamic world governed by progress, by production, hers was a remarkable, even radical, stance. No wonder the woman who would become legendary only in the penumbra of Isamu Noguchi would write to him, when he was only 22, of one of his early sculptures: “I still think Undine is so far your masterpiece, if one may make such discriminations which I don’t believe in, as each one is a masterpiece considered by itself.” Speaking, perhaps, of her own life, then only partially unfolded, she continued: “There is an audacity, a sort of defiant impudence about Undine — you know she is defying life and is going to suffer for it.” 15 years earlier, she had confessed to a friend, after their breakup: “Honestly I do love Yone…[but] it is a relief.” To love, even fool heartedly, was not foolish to Léonie. To squander a scholarship on Paris, to follow a man to Japan, to stay for 17 years — to have written and not published, to have written and lost, to not have written at all — none of it was wasted. “My memory is like a treacherous sea,” she wrote to her son. “Sometimes, it’s true, the tide ebbs, and behold [the memories] are all there — somewhere — oh very safe. All quite equal in value.” Each one a masterpiece in itself – all quite equal in value. Léonie, artist, writer, mother, was remarkable for what she wrote, created, and inspired. But she was also remarkable for something difficult to point to: the simple, fleeting beauty of a life well-lived.